|

ROSNEATIH peninsula, or the

"Island of Rosneath," as it used to be styled in some of the old title

deeds, from its beautiful situation, and salubrious climate, possesses

advantages which enhance the value of the properties comprised within its

bounds. The air is pure and healthy, and the refreshing rainfall encourages

the profusion of ferns, mosses, and the perennial verdure so grateful to the

eye. It is not easy to trace back the various owners of the lands, which

seem frequently to have changed hands. They were possessed in 1264 by

Alexander Dunon, who became indebted to the King, and his property was

burdened until he could deliver over 600 cows at one time. Afterwards they

became the property of the Drummonds, ancestors of the noble house of Perth,

who agreed to assign over to Alexander do Menteith the whole lands of

Rosneath as an "assythment" for the murder of his brothers. Part of the

peninsula at one time was in the possession of the ancient Scottish family,

the Earls of Lennox, who owned so much of the territory on the opposite

shores of the Garelocb. But about the year 1425, the head of that family',

and various of his near relations, were put to death at Stirling. And, in

1489, the Earl of Lennox, baring been engaged in treasonable undertakings,

his lands were confiscated, although, as appears from the records of the

Scottish Parliament, he was pardoned for the offence. Still the forfeiture

of his lands was not withdrawn, for, in 1489, the property of Rosneath was

awarded to Colin, first Earl of Argyll. Thus the greatest part of the

southern half of the peninsula was conveyed to the Argyll family, whose

genius has so §trongly- impressed itself upon the history of their country

and clan. There were several other properties in Rosneath, such as those of

Campbell of Peatoun, Campbell of Rachean, Campbell of Mamore, Campbell of

Carrick, Cumming of Barremman, some of which only came into possession of

the Argylls well in to the eighteenth century.

Beginning at the upper end of

the peninsula, near Gareloch-head, the estate of Fernicarry, known in early

days as Feorling breck, or Fernicarr, was, in 1545, held by the Colquhouns

of Luss, as were also the adjoining lands of Mamore and Mambeg. They passed

to the family of Campbell of Ardkinlass, who, at that time, were

considerable proprietors in "the island." Mamore afterwards became the

territorial designation of John Campbell of Mamore, second son of Archibald,

ninth Earl of Argyll, who succeeded to the Dukedom in 1762. The estates of

Meikle and Little Rachean, with the lands of Altermonyth, or as it came to

be known, Peatoun, were given by King Robert I. to Duncan, son of Mathew of

the Lecky family. This grant included that of the office of hereditary

sergeant of Dunbartonshire, and was long enjoyed by the family of Lecky or

Leckie. The Rachean estate was subsequently acquired by Robert, the younger

son of Campbell of Ardkinlass, and afterwards by John Campbell of Mamore.

Peatoun, a beautifully situated property on the shores of Loch Long, was

purchased by John Campbell, son of the proprietor of Rachean, from Campbell

of Skipness. He was one of the Commissioners of Supply in 1715, and died

without lawful issue, but his illegitimate daughter, Margaret, married in

1721 John Smith, a son of his wife by a former marriage. This man was

concerned in the notorious Peatoun murder, for John Smith was convicted of

killing both his wife, and his own sister, and was hanged in Dunbarton for

the crime in 1727. The Peatoun estate is now owned by Lorne Campbell, who

chiefly resides in Canada, it having come into this branch of the family in

virtue of the disposition, in 1810, by Donald Campbell of Peitoun, or

Peatoun, in favour of the heirs of the Rev. William Campbell, minister of

Kilchrenan in Argyllshire. The Peatoun family are the representatives of the

Campbells of Rachean, and, according to the genealogical tree of Ardkinlass,

and to the belief of the last baronet of the family, Peatoun might establish

his claim to the title, and also head of that ancient and powerful branch of

the house of Argyll. Peatoun was, for a short time in the sixteenth century,

in the possession of CampbelI of Ardentinny; the name Altermonyth, or Alt-na-mona,

signifies "stream of the moss."

Adjoining Peatoun is the

small property of Douchass, or as it is now called, Duchiage, which belonged

to Stewart of Baldarran in 1465, but, in the middle of next century, it was

purchased by Campbell of Carrick, from whose possession it passed into that

of the Argyll family. Still keeping to the Loch Long side we come to the

lands of Knock Barbour, granted to the church of Dunbarton by the widowed

Countess Isabel of Lennox; at the Reformation it was acquired by the

Cunninghams of Drumquhassil, and then by the Ardkinlass family. Knockderrie

belonged in the sixteenth century to a Mackinnie, extending in those days to

five lib. land. On the rocky headland once stood what was said to be a

Danish, or more probably a Norwegian fort; erected at the time,

"When Norse and Danish gallies

plied

Their oars within the Firth of Clyde,

Then floated Haco's banner trim,

Above Norwegian warriors grim,

Threatening both continent and isle."

The contiguous farms of

BIairnachtra, Cursnoch, Ailey, Aiden, Port-kill, and Kilcreggan, formed part

of the possessions of the Campbells of Ardkinlass, and from them went partly

to their cadet the Captain of Carrick, and partly to the Earl of Argyll.

PortkiIl at one time attained to the importance of being a burgh of barony.

Returning to the Gareloch

side of the peninsula, we come to the compact property of Barremman. This

estate at one time was owned by Campbell of Ardentinny, and, in 1871, was

sold by its then proprietor, the late Robert Crawford Cumming, to Mr. Robert

Thom, of the Isle of Canna. It was acquired by Walter Cumming, styled

"in-dweller in the Clachan of Rosneath," of date 13th March, 1706, from

Daniel Campbell, Collector of Newport, in return for a " certaine soume of

money, as the full and adequate pryce of the lands aforesaid." These

comprised 'all and haill the lands of Clandearg (Clynder) and Boreman,

extending to a seven merk land of old extent, with the yards, houses,

orchards, parts, pendicles, and universell pertinents of the same lying in

the Isle and Baronie of Rosneath, and Sheriffdom of Dumbrittaine."

Proceeding along to what is known as the Kirkton, or Clachan, of Rosneath,

close to the old church there, is the family mansion house, which was added

to by the Honourable John Campbell, of Mamore, when he acquired the estate,

with the much-admired famous yew tree avenue with its sheltered walk of

sombre shade. In the 16th century these lands were owned by another family

of Campbells, and by a branch of the Macfarlanes in the following century.

Beyond this, again, is Camp-sail, which for generations was the property of

the Campbells of Carrick, who built here an old mansion, traces of which

still remain near the celebrated silver firs, the great botanical glory of

Rosneath. On the shores of the lovely Bay of Campsail, one of the most

admired in all the beautiful Frith of Clyde, was heard, in 1662, a most

remarkable echo, and described by Sir Robert Murray in the transactions of

the Royal Society. He got a trumpeter to sound a tune of eight semi-briefs,

and then to stop, as the trumpet ceased, the whole notes were repeated,

completely, in a rather lower tone ; when these stopped, another echo took

up the cadence in a still fainter tone, and finally a third echo resounded

the notes once more, with wonderful softness and distinctness. The Campsail

property was added to the Argyll estate at the death of John Campbell of

Carrick, who married Jean, the daughter of the Duke of Argyll, and fell

fighting gloriously at the battle of Fontenoy, in 1145. Beyond this are the

policies of Rosneath Castle, the fine building itself forming a conspicuous

object on the land-locked bay. The old castle, which was destroyed by fire,

was described by George Campbell, a century ago, in an old manuscript, as a

11 good house most pleasantly situated upon a point called 'The Ross,' where

they have good planting and abundance of convenience for good gardens and

orchards."

From the statistical account

of Scotland of 17°2, some details may be gleaned regarding the parish of

Rosneath which were furnished, at the time, by the Rev. George Drummond.

Apparently the parish could sufficiently supply its inhabitants with

provisions, if they were not obliged to sell their produce for ready money

in order to pay their rents. The population of the peninsula, according to

Dr. Webster, was 521; amongst whom were 7 weavers, 3 smiths, 4 shoemakers, 5

tailors, 96 herring fishermen, K seceders, and 14 Cameronians. The annual

rent of a cottage and yard was from ten to twenty shillings. The fish

commonly caught were cod, mackerel, skate, flounders, herring and

salmon,—the latter fish sold from Id. to 3d. per pound. One salmon fishery,

with price of ground attached, Iet for £30 a year.

There were no villages in the

peninsula, but 98 dwelling-houses, all detached, scattered over its surface.

The average stipend of the parish, including the glebe, was £110, which, as

now, was paid by the three heritors, the Duke, Campbell of Peatoun, and

Cuming of Barremman. The educational wants of the population were met by a

schoolmaster who enjoyed the modest salary of £8 9s., while, in addition,

other fees and perquisites amounted to £8 7s. In winter the number of

scholars was 38, and £18 was the annual amount raised for support of the

poor. The provisions in use in the parish were of the usual kind, customary

in rural districts of Scotland. The cost was small, compared with prices of

the present day ; beef and veal, 5d., mutton, 4d. to Gd. thn pound. A good

hen cost is., a chicken, 4d.; butter was 9d. to Is. the pound; oats sold for

13s. the boll. The wages of a common labourer, without victuals, were 10d.

to 1s.; joiner, 2s. a day; mason, 2s.; and a tailor 8d. a day, and his meat.

The common fuel used by the cottagers was peat, only a few families burning

coal, which cost 5s. per cart.

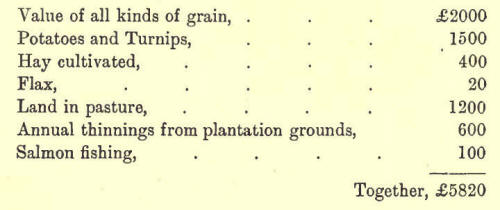

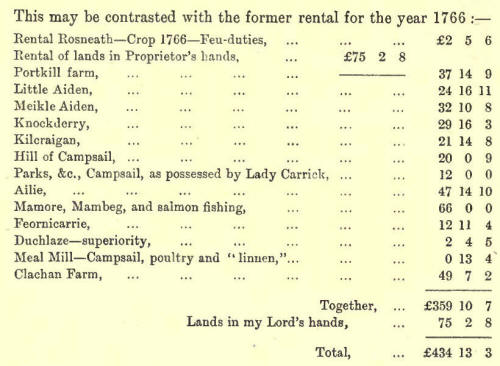

Prices had somewhat advanced when the Rev. Robert Story drew up his account

of the parish in May 1839. It appeared there were then over 3000 acres of

uncultivated moorland, of which 500 were considered capable of profitable

culture, 520 were under valuable wood plantations of various sizes, and 720

were of old and natural copse wood. At that time the average value of land

under the plough might be about £1 as. per acre, the charge for grazing a

cow £2 10s., and a sheep 5s., the total rental of the peninsula being esti

-mated somewhat under £3,500. In 1792 the amount of land rent was given as

£1000. In 1839 the agricultural labourer received 1s. 10d. and artisans 2s.

6d. per day, farm servants being hired at £7 and £8 for the half-year, with

bed, board and washing. The average yearly value of all sorts of produce was

then about £5,820, which was arrived at as follows:—

In former years there were

many more farms on the Rosneath peninsula than now, where there are about

fifteen, and the remains of the steadings may be seen on the high road

between Kilcreggan and Peatoun. At Barbour farm, near Peatoun, there used to

be two rows of thatched cottages, near the road-side, and about fifty

families altogether lived on the farm, which was let in four parts to

different tenants, and amongst them were twenty cows and four horses. The

farm of Cursnoch was formerly let by itself, though now part of the large

holding of Knockderry. Cursnoch was long occupied by Mr. William Chalmers,

the name being often pronounced and also written as Chambers. His rent for a

number of years from 1800 was £76, and at that time the tenant paid a

portion of the minister's stipend, road-money, and land cess. The following

receipt by the old minister, Dr. Drummond, shows how he drew his stipend

direct from the farmers:-

"Roseneath, 22 Feby., 1797.

Received six shillings and three pence the Vicarage Teind, Furth of Cursnoch,

for cropt and year seventeen hundred and ninety-six.

GEO. DRUMMOND."

The "horse and house duty"

for year for \Vhitsunday 1798 to 1799 was 15s. 4d. In 1808 the farmer pays

4s. for window-duty, and 12s. 6d. for a draught horse. In 1811 the duty on a

draught horse was 14s. In 1813 the farmer had to pay 3s. a gallon for his it

"all" in Greenock, and a few years later his candles cost him 9d. the pound

; ordinary sugar, 9d. the pound, and loaf-sugar Is. 3d. the pound ; while

for his tea he had to pay no less than 8s. per pound. In the year 1800 the

local smith at the clachan of Rosneath charged Mr. Chalmers 1s. 4d. for a

"potato hoe;" a "hoop," 7½d.; for one "horse shoe of my iron," 9d.; for four

shoes "made of your iron," 1s. 4d.; "2 removes," 6d. Coals in the year 1829

were only six shillings the cart, less than half what is now charged. In

1831 the price of a pound of tea was 6s.; brown soap, 7d. the pound; sugar,

7d.; soda, 4d. The practice seems to have been for the tailor to come to the

farmer's house and make clothes for the family. Accordingly, in July, 1817,

Duncan "Chambers" charges "William Chambers" for a "suit to your son, 16s.,"

and "coat to your self, 8s. 6d." Teaching, however, is very moderate, for

Andrew M'Farlane only charges for 11 teaching James 3 months 4s. 3d." The

family doctor's account is to "John Reid, Surgeon, four visits to family,

bleedings and medicines, £2 5s. 8d." So that it can be seen that the cost of

living was, in most respects, considerably dearer to the farmer seventy

years ago.

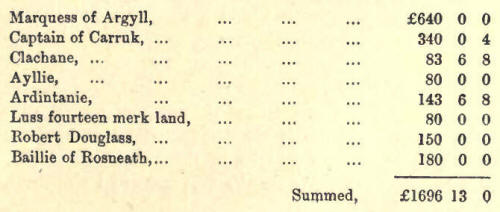

In Irving's History there is

given the rental of the parish of Rosneath, taken from a copy of the old

Valuation Roll, which was subscribed by the Commissioners of Supply in the

year 1657, as follows:-

This is from an old rental,

and would be in Sterling money. In the Blue Book of the heritages of

Scotland, published a quarter of a century ago, the agricultural rental

value of Rosneath estate was stated at £5,170. At the present time,

including feu-duties, the rental of the estate is over £8000 per annum.

Upwards of a century ago the

herring-fishing was a source of much profit and occupation to many who

resided on the shores of the Gareloch and Loch Long. The owners of the

fishing-boats resided all along the loch side, from Row on to Faslane Bay,

Garelochhead, Rahane, Mamore, Crossowen, Clynder, Campsail, and the Mill

Bay, thence over to Kilcreggan, Cove, and as far as Coulport on Loch Long,

where the Marquis family, notable as fishers and ferrymen, resided for

nearly one hundred years. The late Mr. James Campbell of Strouel, himself an

experienced fishery man, widely known and greatly esteemed, told the author

that he could remember well when over 100 fishing-boats would be in the loch

at one time, a good number hailing from ports on the east coast and

elsewhere, The boats were large two-masted ones, half-decked, and they went

to all the lochs on the west coast in the season, three men to each boat.

The herrings were so plentiful, that it was no unusual thing for one boat to

get as many as ten thousand herrings in one night, and the fish sometimes

sold as low as sixpence for a hundred. Quantities of herrings were shipped

by the Alma from Garelochhead for Glasgow, which left at half-past five in

the morning, loaded to the water's edge with fish. The buyers came from

Greenock, and often their custom was to go from boat to boat in the evening,

before fishing commenced, and distribute bottles of whisky to the crews, a

bottle to each boat, on the understanding that they got the night's take at

a reasonable price, which was to be made up amongst the buyers. However,

about 1827, the herring-fishing began to fall off with the advent of

steamers up the loch, and very few boats went out, as the fish ceased to

frequent the lochs in anything like the former quantity. Still, every few

years there are great shoals of herring which come up the Gareloch to their

favourite waters at its head. Salmon, also, were tolerably abundant, and

there were stake-nets at different stations on the Gareloch and Loch Long,

where many fish were got. A very pleasing feature in former years was the

Sabbath morning worship, which was regularly conducted on board the

herring-boats, the strains of praise and the solemn accents of prayer

arising from the simple fishermen, and were wafted across the placid waters

of the loch.

Steamers began regularly to

appear in the Gareloch and adjoining waters before 1830, but the open

packet-boat, or wherry, still made the passage from Rosneath Inn and

Kilcreggan old pier to the surrounding ports. The wherry would take a good

quantity of farmproduce—sheep, cattle, horses, and other animals—to Greenock

and Gourock, with probably a considerable number of passengers in addition,

and generally used sailing power in preference to oars, while in the fogs

which occasionally prevailed they had to be steered by compass. For the

conveyance of the Duke of Argyll and his friends on the occasion of their

visits to the district, his Grace's emblazoned six-oared barge plied between

Cairndhu point and the castle. The barge was signalled from Cairndhu by

means of three fires or smokes if the Duke and Duchess were to be

transported across the channel ; two smokes for relatives and friends; and

one smoke for those in a humbler position in life—flashes of flame

regulating the traffic after dark.

Smuggling was quite an

occupation in Rosneath in the early part of the century, and many are the

stirring reminiscences of some very old natives with reference to this

violation of the excise laws, which in those days was considered a venial

offence. The formation of the parish rendered it highly suitable for such

operations, which were carried on by some of the younger fishermen, who

found a ready market for their illicit produce at Dunbarton, Greenock,

Port-Glasgow, and other towns. Several of the burns on the Rosneath side,

near Strouel and Clynder, were haunts of the smugglers, the one running into

Strouel bay in particular. It was the practice for the revenue cutters to

keep a sharp look out for smugglers, although they were, as a rule, much

more lenient in their operations than the regular Dunbarton excisemen. On

one occasion the crew of a revenue cutter landed on the Peatoun shore, and

all but took red-handed a number of smugglers engaged at their trade. Soon

the news spread, and the natives emerged from their crofts—men, women, and

boys—and a goodly array confronted the revenue men as they were triumphantly

carrying off the spoil. Thus emboldened, they encountered the revenue

officials, who demanded that they should not be molested in the discharge of

their duty, but, owing to the force of numbers, were compelled to yield up

the booty they had. Shortly after the latter reached the cutter, the

exulting array of Rosneath natives were defiantly surveying the offending

vessel, when all of a sudden the latter sent two or three cannon shots

amongst the astonished crowd of spectators. Fortunately no one was hurt, but

they heat a rapid retreat, and kept discreetly in seclusion the next time

the cutter made her appearance on a voyage of investigation.

At Rosneath, in former days,

marriage ceremonies were attended by somewhat boisterous crowds, and on the

intermediate days before the "kirking," the young couple and their jubilant

attendants, preceded by a bagpiper, perambulated the parish from house to

house, visiting their friends. The nuptial rejoicings were closed by the

whole party, after divine service on the Sabbath, adjourning for

refreshments to the nearest tavern, and a scene of unseemly mirth and

riotous festivity too often ensued. Baptisms were frequently desecrated by

the accompanying conviviality, and, after the service in church, the friends

and relatives proceeded to the inn, and indulged in copious libations of the

national beverage. Even funerals sometimes partook of the character of

orgies, and it was considered that becoming honour to the departed

necessitated at least four different distributions of spirits. On the farms

round the Gareloch, also, some curious customs lingered on till about "sixty

years since." One of these was the cutting of the last sheaf of corn—the

"maiden," as it was called here and elsewhere in Scotland—and this sheaf,

usually adorned with parti-coloured ribbons, was hung up in the farmhouse,

and allowed to remain for months, even sometimes for years, the momento of a

prosperous harvest.

Miss Macdougal, one of the

old natives of the parish, who still resides in the cottage in the Clachan

village built by her father, remembers a good many of the old inhabitants

and their primitive ways. Her father used to describe the former

pre-Reformation church, which stood almost on the site of the existing

ruined fabric. It was a handsomely decorated building, of cruciform shape,

with a row of images round the pulpit, a finely carved font for holy water,

and the staircase leading up to the family pew of the Duke of Argyll. OId

Mr. Macdougal was of an hospitable turn of mind, and was fond of

entertaining the natives on their holiday occasions, when they assembled for

their favourite shinty sports. On New Year's day there was generally a great

shinty match played in the "barn" park, when Mr. Lorne Campbell and his men

came with a piper, the laird of Barremman and his piper, and Archibald

Marquis, of the Ferry-house at Coulport, accompanied by a piper, and the

company indulged in various games. After the sports were over, Lorne

Campbell, Barremman, and others, came to Macdougal's and got refreshments of

whisky and oat-cakes. On the first day of the year there was always a dinner

at the old Clachan house, where the Campbells of Peatoun lived for many

years as tenants of the farm, and sometimes the attractions at Macdougal's

and at the Ferry Inn kept the company so long that the dinner would suffer.

The shinty match was the great festival of the year, and hundreds assembled,

old and young, with music and banners, to see the play; and a dance at the

inn, which was prolonged till dawn of the following day, finished the

proceedings.

Both Dr. Story and Dr. James

Dodds, formerly of Glasgow, now minister of Corstorphine, and natives of the

parish, can recall some of the primitive ways of the inhabitants. They

remembered the old "tent," as it was called, used on sacramental occasions,

and the curious box where the watchers remained all night on the look out

for "resurrection men," as they were termed in those days. On the Sabbath

mornings, fifty years ago, the workers and families from the farms on the

Loch Long side would cross the moor, and descend the braes above the

Clachan, the women stopping to bathe their feet in the burn before entering

the church. In those days only three houses on the loch side regularly took

in loaf-bread, which was carried from Helensburgh, and across the ferry from

Row, by the well-known "Gibbie" Macleod. In some of the farm-labourers

cottages, bread only was known, perhaps, three or four times in the year,

being brought from the Clachan at the half-yearly "preachings," and at the

New Year's holiday. Half an ox side of beef was salted and laid in at

Martinmas, and an occasional joint of pork, with abundance of salted

herrings, constituted the larder of the cottagers. Porridge was then the

main stay of the diet of both children and their elders; such a luxury as

tea was only known, very sparingly, on Sunday mornings, and coals were

rarely used, peat being the universal article provided for fires.

Seventy years ago the farms

were, in many cases, but indifferently cultivated, and only a short time

previously there were no dykes or fences on the ground, and the cattle were

herded by children. One venerable native of Rosneath, the widow of Archibald

Marquis of the Coulport Ferry, can remember the building of most of the

walls on the Duke's farms. There were then very few sheep in the peninsula,

and the farmers twice in the year attended the Dunbarton and Balloch

markets, while drovers came to Rosneath from time to time and bought cattle

for transport both to the Highlands and low country. The father of Mrs.

Marquis put up a small thatched house for the purpose of a school at Letter

farm, and in this humble edifice, which had four small windows, and a hole

in the roof to serve for a chimney, the schoolmaster, John Chalmers, taught

the children. The master came for a fixed period, and generally stayed with

one of the farmers, getting his board and very small fees for remuneration.

On the Barbour farm there was a similar old school, even humbler in its

furnishings, for the boys and the master, Andrew M'Farlane, who had lost an

arm, used to sit round the peat-fire, piled up in the middle of the floor,

on stormy winter days. The seats were one or two planks placed on lumps of

turf, and there was a long form at one end at which the boys wrote, each

scholar being expected to bring a contribution every day in the shape of a

large peat for the common good. The good old implement of flagellation,

known as the "tawse," was in frequent use, for the former school of teachers

had implicit confidence in this gentle art of persuasion. Later on there was

rather an original character, James Campbell, from the Arden-tinny side, who

acted as teacher, and he would enjoy his pipe while imparting instruction,

and one of his pupils remembered how the master, when finished with his

smoke, would pass the pipe to the nearest boy, from whom it circulated

through the class. In 1834 there was yet another school, a well-built,

small, stone house, close beside the Dhualt burn, on what was formerly

Blairnachter farm, erected by the Duke of Argyll and his tenants for the

benefit of the children on that side of the peninsula, and frequently used

as a place for public worship by the Rev. Robert Story, before the church at

Craigrownie was built. [Kilcreggan school. This school, which was largely

endowed by the late Lorne Campbell, the Duke's Chamberlain, serves for the

children of this side of the peninsula. Mr. William M'Cracken, the able and

efficient teacher for over thirty years, fills other responsible offices in

the district.]

Clothing in those days was

supplied to the farmers and cottagers by the tailor and shoemaker coming

with their cloth and leather, and remaining until they had made the needful

garments and shoes for the family. Weavers also would come from Greenock to

get the home-spun cloth, to be finished and dyed. All the lights used in the

farm-houses were the old-fashioned cruizie; and the children, on the bright

moonlight nights, would amuse themselves gathering rushes to furnish wicks

for the home-made tallow candles. Letters were but seldom received, the

postage from Glasgow, sevenpence halfpenny, being prohibitory, and in early

days they used to lie for weeks at the old Ferry Inn at Rosneath. Later on,

however, Donald Brodie, the postman, walked from Dunbarton to Row and

crossed to Rosneath, leaving at 3 p.m. for Dunbarton again. This feat was

eclipsed, however, by Brodie when he contracted to deliver letters all the

way to Garelocbhead, walking there and back to Dunbarton six days in the

week.

In the days when the Marquis

family kept the Coulport Ferry, in the early part of the century, the old

ferry-house was in what is now part of the Milnavoullin feu, and it is still

used as a dwelling-house. The new house is beside the modern pier put up by

the Duke, and has not the same amount of accommodation as the former, which

was also an inn, where belated travellers could remain all night when the

crossing was dangerous. There were four different farmers on what is now the

Barbour farm, and others of the existing holdings were then subdivided. At

Barbour farm and at Peatoun there were various thatched cottages, and at

Rahane a row of red-tiled ones, all of which have long ago been pulled down.

On Ailey farm there were eight families of crofters, where none now are, and

there was a regular settlement of crofters on Blairnachter. At one time, it

is said, there was a small hamlet of thatched cottages on the edge of the

moor above the Clachan braes, but no trace of these can now be discovered.

At the farm of Mamore there is a substantial house, which was built by the

father of Mrs. Bain, who resides at Cove, and she recollects, as a child,

the then factor of the Duke coming to her father, who was intending to

repair the old farm-house, and telling him that he would supply stones,

slates, and windows from the old castle of Rosneath. Robert Campbell of

Mamore, the grandfather of Mrs. Bain, knew the far-famed Rob Roy, so dear to

all lovers of romance in history, and encountered the hero on Loch Long side

once, when the military were in search of him. As the danger seemed

imminent, it was agreed that an exchange of clothing should be made, and,

shortly afterwards, the soldiers came up, and were greatly enraged at

finding they had run down the wrong man, for by this time Rob was well on

his way to one of the glens leading to Loch Lomond. One morning after this a

fine cow was found on the farm, and not claimed by any of the neighbours,

and this was understood to be Rob's mode of showing his gratitude. Her

grandfather remembered of an unwelcome visit from the "Athole raiders," as

they were known, who searched the country for cattle, but as they had all

been driven away to a remote hiding-place under the cliffs beyond Portkill,

the invaders were baffled. It was also matter of tradition that a fight once

took place between a body of raiders and the natives of the "Island," near a

green knoll at the march dyke bounding Knockderry farm, and this spot,

probably from the dead buried beneath the turf, came to be known as the "Highlandman's

Knowe."

It was no unusual matter,

even in this remote part of the county, for attempts at robbery and "hereship"

to be made. From the Burgh of Dunbarton Criminal Records we learn that

Duncan Glass M'Allum was convicted in August, 1687, of going to Rosneath in

company with a party, "that he got his shaire, three young kyne and a stirk,

confesses that there were uplifted at the foirsaide time about a hundred

kyne and horse, and some sheep; and confessed that he was in Patrick

Cummin's house with the rest, when it was robbed, but denyes be midled with

anything himself that was therein, and that those who robbed it were the

personnes that took away with him the foresaide herschip." Proof being led,

it was found that the accused had threatened one of the witnesses, and

compelled him to swear that he would not give information, and the

unfortunate M'Allum was sentenced to be hanged on the 26th of August, in the

afternoon betwixt the hours of two and four.

The "Peatoun murder" was a

dreadful tragedy, perpetrated by John Smith, who had married the daughter of

the laird of Peatoun, and thereafter assumed the name of Campbell. The

marriage took place in 1721, and, on 15th December, 1725, his sister's dead

body was found in a pool of water, not far from the mansion house of Peatoun,

near a place she was often in the habit of passing over the moor. The body

was carried to Mamore, her brother John's house, and on the day of her

funeral he consulted a lawyer about the recovery of a sum of money which was

to fall to him in event of her death without issue. As yet there was no

suspicion of her having met with her death by foul means. On 3rd September,

1726, after John Smith had taken breakfast with his wife, they were seen to

go together towards the Mill of Rahane, but on different sides of the glen.

She was never seen alive again, and the husband helped in the search, and,

when her dead body was discovered near Mamore, his residence, he seemed in a

distracted state, although he directed the servants to attend family worship

as usual in the evening, shewing great agitation when he read in the Psalms

at worship threatenings against violent and bloody men. Some days

afterwards, suspicion was directed against John Smith, or Campbell, and he

was apprehended in the churchyard of Rosneath, where he was attending a

funeral. Certain papers were found at Peatoun gravely incriminating Smith,

and ultimately he confessed his awful crimes, admitting that he had

premeditated both the murders a considerable time before he accomplished

them. His sister he threw into the pool of water, and on her recovering

herself, and crying out, "Lord preserve me," he deliberately kept her head

under water until she died. The unfortunate wife was thrown into the pool

with such force that she received some cuts on the head from the rocky side,

but thinking that it would not favour his design of concealing the murder to

leave her in the water, he took the body in his arms, and carried it some

little way off to the place where it was afterwards found. The murderer was

executed at Dunbarton on 20th January, 1727, and made an edifying profession

of penitence on the scaffold, entreating the spectators not to encourage

themselves in secret sins, in the hope of their not being discovered, for he

had no peace of mind after the murder of his sister. His motive for the

double murder was in consequence of a guilty passion which he had formed for

one of his wife's bridesmaids, at the time of the marriage, and an oath

which he had taken to her to give her 1000 merks if she would agree to marry

him in event of the death of his wife within a certain time. John Smith was

attended to the place of his execution by several ministers of surrounding

parishes, and, after they had suitably exhorted him, all present prayed most

fervently for the murderer, and it was believed that the solemn scene had a

most powerful effect upon all.

Mention has been made of some

of the eminent men, chiefly belonging to the Argyll family, who resided in

Rosneath. During the persecuting times of the later Stewart kings, some

notable lowland Presbyterians, such as Balfour of Burley, Chalmers of

Gadgirtb, and others, found their way to the peninsula, as the names and

traditional histories of several families indicate. One who must be always

held in honour was John Anderson, the well known founder of the Andersonian

Institution of Glasgow. This distinguished man was born at Rosneath manse in

the year 1726. Ile was the eldest son of the Rev. James Anderson, the parish

minister. While residing in the town of Stirling he received the rudiments

of learning, but the more advanced portion of his education at the college

of Glasgow, and he was chosen to be professor of oriental languages in that

institution while just thirty years of age. In 1760 he was appointed to the

chair of natural philosophy, and entered upon its duties with an enthusiasm

rarely equalled, for he visited all the workshops of the artificers in town

for the purpose of gaining experience in the details of manufactures. He was

elegant in his style as a lecturer, with a great command of language, and

the skill and success with which his manifold experiments were performed

could not be surpassed. Nothing delighted him more than hearing of any of

his pupils distinguishing themselves in the world. The only distinct work

which Mr. Anderson published in connection with the science of natural

philosophy was the Institutes of Physics, a valuable contribution, which

appeared in 1786, and went through five editions in the next ten years.

Mr. Anderson's sympathies

were on the side of the people at the beginning of the French Revolution,

and he had invented a gun, the recoil of which was stopped by the

condensation of common air within the body of the carriage. His model of the

gun he took to Paris in 1791, and presented it to the National Convention.

The Government, seeing the benefit to be gained from the invention, ordered

Mr. Anderson's model to be hung up in the public Hall, with the following

inscription over it: "The gift of Science to Liberty." He made numerous

experiments near Paris with a six-pounder gun, and amongst those who

witnessed them was the celebrated Paul Jones, who gave his strong

approbation of the gun as likely to be very useful in landing troops from

boats, or firing from the decks of vessels. He assisted with his advice the

Government in devising measures to evade the military cordon which the

Germans had drawn round the frontiers of France, and was present when the

unfortunate King, Louis XVI., took the oath to the Constitution in Notre

Dame Cathedral.

Mr. Anderson died on 13th

January, 1796, in the 70th year of his age, and directed by his will that

the whole of his effects should be devoted to the establishment of an

educational institution in Glasgow to be called Anderson's University.

According to the design of the founder there were to be four colleges, for

arts, medicine, law, and theology, besides an initiatory school. Each

college was to consist of nine professors, the senior professor being the

president or dean. The funds, however, being inadequate to carry out Mr.

Anderson's design, the college was commenced with only a single course of

lectures on natural philosophy and chemistry by Dr. Thomas Garnett, known as

an author of scientific and medical works. This course was attended for the

first year by nearly a thousand persons of both sexes. In 1798 a professor

of mathematics and geography was appointed. In 1799 Dr. Garnett was

succeeded by the eminent Dr. Birkbeck, who, in addition to the branches of

instruction taught by his predecessor, introduced a familiar system of

philosophical and mechanical information to five hundred operative

mechanics, free of expense, thus giving rise to mechanics institutes. The

Andersonian institution was placed under the inspection and control of the

Lord Provost, and other influential citizens, as ordinary visitors, and

under the more immediate superintendence of eighty-one trustees, who were

elected by ballot, and held office for life. This admirable institution,

which has only within the last two years been incorporated with the

Technical College, Glasgow, for nearly a century gave instruction, on very

reasonable terms, to thousands of students. There was a staff of professors

who taught surgery, institutes of medicine, chemistry, practical chemistry,

midwifery, practice of medicine, anatomy, materia medica, pharmacy, medical

jurisprudence, mathematics, natural philosophy, botany, logic, geography,

modern languages, English literature, drawing, painting, and other branches.

The institution possessed a large and handsome building belonging to the

Corporation, also an extensive museum, and was a striking example of what

can be done by one man of no very great resources for the benefit of his

fellow-creatures. The name of the founder has now dropped from the old

building in George Street, so dear to the memory of thousands of grateful

hearts, who recall their happy hours of generous emulation with those who

have long passed away. But the medical branch of this useful institution is

perpetuated under the name of "Anderson's Medical School" at Partick, so

that succeeding generations of students will yet have cause to cherish the

honoured name of John Anderson.

Matthew Stewart, one of the

most distinguished of Scotch mathematical scholars, and father of the famous

Dugald Stewart, was for some years minister of Rosneath. He was a man of

eccentric habits, and was wont to perambulate for hours, in absorbed

meditation, in the old yew-tree avenue. The well-known Dr. Alexander

Carlyle, the minister of Inveresk, visited the parish on his way to

Inveraray in the month of August, 1758. In his journal he relates:—"From

Glasgow I went all night to Rosneath, where, in a small house near the

castle, lived my friend, Miss Jean Campbell of Carrick, with her mother, who

was a sister of General John Campbell of Mamore, afterwards Duke of Argyll,

and father of the present Duke. Next day, after passing Loch Long, I went

over Argyll's Bowling Green, called so on account of the roughness of the

road." Another Carlyle, still more renowned than the imposing and eloquent

leader of the "Moderates" in the Church of Scotland, seems to have visited

Rosneath in August, 1817. In Fronde's Reminiscences the visit is thus

recorded: "Brown and I did very well on our separate branch of pilgrimage;

pleasant walk and talk down to the west margin of the Loch incomparable

among lakes or lochs yet known to me; past Smollett's pillar; emerge on the

view of Greenock, on Helensburgh, and across to Rosneath manse, where with a

Rev. Mr. Story, not yet quite inducted, whose life has since been published,

and who was an acquaintance of Brown's, we were warmly welcomed and were

entertained for a couple of days. Story I never saw again, but he acquainted

in Haddington neighbourhood some time after, incidentally, a certain bright

figure, to whom I am obliged to him at this moment for speaking favourably

of me. Talent plenty, fine vein of satire in him, something like this. I

suppose they had been talking of Irving, whom both of them knew and liked

well. Her, probably, at that time I had still never seen, but she told me

long afterwards. Those old three days at Rosneath are all very vivid to me,

and marked in white. The quiet, blue mountain masses, giant Cobbler

overhanging bright seas, bright skies, Rosneath new mansion (still

unfinished and standing as it did), its grand old oaks, and a certain

hand-fast, middle-aged, practical, and most polite Mr. Campbell (the Argyll

factor then), and his two sisters, excellent lean old ladies, with their

wild Highland accent, wire drawn, but genuine good manners and good

principles, and not least, their astonishment and shrill interjections at

once of love and fear over the talk they contrived to get out of me one

evening, and perhaps another when we went across to tea; all this is still

pretty to me to remember. They are all dead, the good souls. Campbell

himself, the Duke told me, died only lately, very old; but they were to my

rustic eyes of a superior furnished stratum of society."

Dr. Thomas Chalmers was an

intimate friend of Mr. Story's, the latter having been introduced to his

charge by that eminent divine. On one occasion, when Dr. Chalmers,

accompanied by Edward Irving, then his assistant, visited Rosneath, an

entertainment was given in their honour by Miss Helen Campbell at her bower,

or sylvan retreat, above the little fall known as "Helen's Linn" in the

Clachan glen, and on this occasion Irving astonished the company by dancing

with marvellous vigour the Highland fling. The rustic bower is now gone, a

retired and sweet spot it was in the shady glen, where, even in hottest

summer day, the visitor felt in a "cool grot," the overhanging old oak and

beech trees twined round with clinging woodbine, scenting the air, and the

mossy rocks glistening with ivy leaves. The gifted Irving was a frequent

visitor to the manse, and he tried hard to persuade his friend Mr. Story to

join the Catholic apostolic body. "Oh, Story," he wrote in 1832, "thou hast

grievously sinned in standing afar off from the work of the Lord, scorning

it like a sceptic instead of proving it like a spiritual man." Sometimes on

sacramental occasions at Rosneath he used to address the large congregations

assembled in the churchyard, speaking from the wooden "tent" which stood

near the manse, and astonishing those present by his weird and dramatic

oratory. He warmly espoused the claims of Mary Campbell to supernatural

gifts and to manifestations of "tongues," and the series of extraordinary

scenes and blasphemous utterances of the excited spiritualists which

occurred in Regent Square Church, resulted in his deposition from the Church

of Scotland. Of those who sought a retired residence on the shores of the

Gareloch in later years, the most notable was the amiable and talented Dr.

John Macleod Campbell, whose writings have had so deep an influence on the

theology of the present day. After his deposition from the Church of

Scotland, Dr. Macleod left the Gareloch, but a few years before his death he

purchased the pleasant residence at Strouel, to which he gave the Gaelic

name of Achnashie, "Field of Peace," and there he died in 1872. His honoured

remains rest in the ancient churchyard of Rosneath, near the beloved friend

with whom he was so long associated in the Master's work.

The geological structure of the peninsula does not require much notice,

nearly the whole strata belonging to the primitive class of rocks. The

prevailing formation is clay slate, which, in certain places, passes into

chlorite slate, and occasionally into mica slate. Here and there beds of

conglomerate may be met, as at the old sea-cliff near Rosneath Castle, and

in one or two parts of the shore. On the high ground above Clynder will be

observed good examples of chloride slate, in the quarries which have been

opened up, the direction being from north-west to south-east. On the shore

of Loch Long, not far from Knockderry, there appears a large mass of

green-stone, lying interposed between the strata. The greenstone is like a

dyke, from twenty to thirty feet thick, and close to it is more of the

chlorite slate rock. Another bed of greenstone is found nearly half-a-mile

further south. The south-western extremity of the parish is pervaded by

conglomerate, and coarse sandstone rock, which occurs in beds of

considerable thickness. This rock is of similar description to the great

sandstone formation which extends along the Renfrew and Ayrshire coasts, and

embraces the Cumbraes and a portion of the southern half of Bute. The line

of formation between the sandstone and primitive rock of the parish runs

along the valley stretching from Campsail Bay to Kilcreggan. In the slate

formation on the Loch Long shore, as well as in the quartz, iron pyrites is

found in considerable abundance. It is crystallised in the slate and in the

quartz appears in large irregular masses. In the colour of the slate there

is much variety, due to the quantity of oxide of iron pervading the

deposits.

In Rosneath are to be found

many birds which are more or less familiar in the west of Scotland. The

extensive woods in the vicinity of the castle, and elsewhere throughout the

peninsula, offer good cover for the feathered songsters, and the range of

moorland insures an ample stock of game birds for the purpose of sporting.

Both grouse ad black game are tolerably plentiful, and these birds may be

seen in considerable numbers in the early morning, when the fields of corn

in the vicinity of the moors are about ready for the reaper, enjoying their

repast off the mellow grain. In autumn and winter, many woodcocks are found,

having arrived in numbers from other countries in their annual migrations.

In recent years, also, there have been several instances of woodcocks

nesting near the "Green Isle" point, amongst the rhododendron bushes and in

the bracken. Snipe will be found to a fair extent in the marshy ground in

the moors, and also about the drains in the higher fields. Pheasants and

partridges are tolerably plentiful, the former bird frequenting the Campsail

and Gallowhill woods, and the familiar chirp of the partridge is heard

amidst the ample fields of turnips. Plovers and curlews are also common,

their pleasant cheery notes salute the visitor wandering along the

unfrequented moor, or over the fields near the Home Farm.

The birds of prey are not so

numerous of late years, as they are looked upon with dire aversion by the

keepers, in their zeal for game preservation. Sparrow-hawks may be seen

sometimes flying around the farm-yards, ready to pounce upon any unwary

chicken, and sometimes they will even dart upon a covey of partridges, and

carry off their prey. This hawk breeds in the high fir-trees in the castle

woods, and also in some of the precipitous faces of rock near Portkill. The

kestrel also is met with, and constructs its nest in the cliffs and rocky

banks, sometimes even at the foot of a rowan tree, where the ground falls

away near a secluded burn. There are plenty of owls in the old woods about

CampsaiI and the Clachan glen, and their melancholy cry may be heard,

especially on moonlight nights, with weird effect. That destructive bird of

prey the hooded crow, is met with on the upper moors, its nest being found

in some retired glen, on a tall fir, or sometimes even a rowan tree, an

unshapely mass of sticks lined with heather and wool. Although the rook

skims over the fields on Rosneath, sometimes in considerable numbers, it

does not seem to fancy the spot for nesting operations, for the only place

where there are a few nests is in the neighbourhood of Knockderry. A good

many of that pert and lively species the jackdaw will be seen in the tall

trees near the Mill Bay, their quick cries resounding amid the firs

overhead. Magpies are not very numerous, but their shrill notes will be

heard in the fir plantations, and their plundering propensities draw down

the vengeance of the gamekeepers.

The Silver Firs, Rosneath |