|

THE kingdom of Denmark,

especially its capital, was threatened by an English fleet: I was

informed that the Government had asked for a French General to undertake

the defence of the country, and that they had thought of me. I will not

deny that I was flattered by the choice, and anxious to join my name to

the events of which that country was to be the scene; but I had the

firmest intention; which I kept, of quitting diplomacy as soon as the

military part of it was concluded. I therefore started for Paris. I did

not expect to get further than Nevers, for, while changing horses in

that town, I heard of the disaster at Copenhagen— abandoned by Sweden,

Russia and Prussia, all of whom were bound by treaties to make common

cause with Denmark. However, on reaching Paris, firmly convinced that my

mission was at an end, the First Consul informed me that there was still

hope of renewing the Quadruple Defensive Alliance, and desired me to

start, via Berlin, promising that, if peace were the result of the

events at Copenhagen, he would grant my request, and recall me

immediately.

On reaching the capital

of Prussia, I soon learned that Russia had broken away from the alliance

by a treaty with England, leaving power to the three other countries to

adhere to it. I immediately sent a special messenger to the First Consul

with this news, and, foreseeing that the other Powers would adhere,

asked leave to return; the answer I received was that, as I had got so

far, I should go on and learn the intentions of the Danish Government,

and that if peace were decided upon my expedition should be regaided as

a mere journey, and I should be recalled at once. I thus went to replace

your mother's father, [Monsieur de Bourgoing, whose daughter became the

Marshal's third wife.] who was awaiting my arrival to go and take up the

same position at Stockholm. I had then no idea that I should ever be

united to your lamented mother, who was then quite young, and whom I had

hardly seen. That was in i8ox, and it was not till more than twenty

years later that the marriage took place, which so sadly terminated in

less than four years.

Previous to my audience

at Court, I was fully confirmed in my opinion that Denmark could never

struggle unaided against so formidable a naval Power as England. The

attack on the capital, the destruction of a large number of her ships,

the successes of the bold and rash Admiral Nelson, who continued to

fight in spite of the contrary orders of his chief, and notwithstanding

a brave defence which merited a different fate, brought about an

armistice which was existing when I arrived, watched by the English

fleet as I passed through the Great Belt. My mission, therefore, brought

about none of the anticipated results, and my first despatch terminated

by an urgent prayer to be recalled. I renewed this prayer for five

months, but as peace was at that time being negotiated with England, it

was deemed advisable to retain foreign ministers at their respective

posts.

The preliminaries having

been signed, [The treaty of Arniens, between France and England, was

signed March 25, 1802.] and peace being momentarily given to all Europe,

it was presumed that the motives I had put forward would no longer

exist. I was therefore sounded with respect to the embassy in Russia,

occupied by General Hédouville, who, like me, was earnestly seeking his

recall. At last I obtained mine, and quitted Copenhagen in the depth of

winter. On my journey I experienced every discomfort of the season,

which was very severe in the North, and after a month of painful,

fatiguing, and even dangerous travel I reached Paris, whence the First

Consul had gone to attend the meetings at Lyons. My stay in Denmark had

not been without interest and pleasure. I was distinguished at Court, on

good terms with the corps diplomatic, and well received in society. I

studied the history of the country—its laws and customs. There I found a

people who, with unbounded love for, and confidence in one of its

sovereigns, blindly abandoned its liberty, and submitted itself to their

absolute power. So far they have had no cause to regret their action,

but I doubt whether any of their powerful neighbours would ever employ

the same generosity in order to guarantee their subjects from the abuses

of violence or despotism.

To return to what

concerns myself. I had a suspicion that Monsieur de Talleyrand had some

motive, that I could not penetrate, for wishing to keep me at a

distance. I had written him strong representations upon this point in

private letters, but as he might have been prejudiced or biased against

me, I called upon him. He received me with cold civility. I warmly

pointed out to him, in presence of his wife and several other persons,

how ill he had behaved, and abruptly quitted his house. Since then I

have ceased to hold any communication with this personage, who

afterwards degraded more and more his name and position. He has

certainly from time to time made overtures to me, but in vain. I had

estimated correctly the sincerity of his affection. His ambition,

however, had been amply satisfied at the Imperial Court as well as at

that of the Bourbons; his supple mind, intrigues, and insinuations had

secured this. When at last Talieyrand came to be better known and

understood, all parties agreed to push him aside, and to let him extract

what enjoyment he could out of a comparatively insignificant office, and

to live in regret, if not remorse. I admit having said too much about

this individual, but it is because I know that he seriously injured me

in the eyes of the First Consul by prejudicing him against me, and

suggesting that I was opposed to his authority.

In 1804 the famous trial

of Moreau commenced, and an attempt was made to implicate me in it by

suggestions of an intimate friendship, which no longer existed. It

seemed, however, to be recognised that my conscience was clear upon that

point, and so I was merely watched, but left in peace.

Shortly after this trial

the First Consul was elected Emperor, and the Government having thus

become monarchical, was invested with the attributes of monarchy. In

order to attain the dignity of Marshal, it was necessary to have had the

command-in-chief of an army, and although this condition was not wanting

in my case, I was not included in the first or in the subsequent lists

of nominations. I therefore had to content myself with thinking that I

had deserved to figure in them, and with the pride' natural to me, added

to the feeling that I was the victim of injustice, I took no steps to

remove groundless prejudices. The time came when I congratulated myself

upon having acted as I did, for circumstances so favoured me that I was

able to win my baton at the point of my sword on the battlefield of

Wagram.

In the year in which the

Legion of Honour was founded, I was first made only Companion, together

with all those who, like me, had received gifts of a sword of honour,

but I was then promoted to be a Knight Companion (Grand Ojilcier). My

name must have passed unnoticed among others, for in the suspected

position in which I then was living, its appearance there could only be

regarded as a favour.

Like everyone else, I had

signed the address of election to the Empire, but rather as a means of

warding off anxieties and annoyances than with any hope of obtaining

reward. I had no reason whatever for opposing it, still less for being

jealous or desirous of it. My isolation chafed me on account of your

elder sisters. They had received an excellent education at Madame

Campan's, but the sight of their friends making brilliant marriages at

the Imperial Court made me dread lest they should become enamoured of

these exalted positions. But their own good sense, their judgment beyond

their years, my advice, and the affection they bore me, convinced them

that I was innocent of this disgrace, and they resigned themselves to

whatever fortune might be in store for them.

I had just bought this

property at Courcelles whence I write to you, and which I intend you to

have some day but notwithstanding the pleasures of a country life, and

the delight of being at rest, my military ardour blazed up at the

accounts of every fresh victory. However, this ardour quieted down when

I remembered that my career was advancing, so much so that it was not

without some alarm that I received orders to join the Army of Italy,

after five years spent in retirement, to put myself at the disposal of

Prince Eugne Beauharnais, Viceroy and Commander-in-chief. I was just

about to return here with your sisters, who had finished their

education, and whom I had removed from school. I was only spending a few

months with them in Paris during the winter to perfect their

accomplishments.

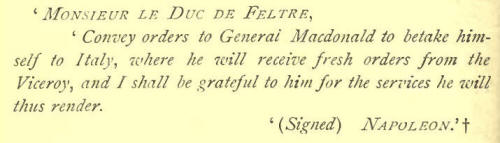

I think I received the

order early in April, and at first I concealed the nature of it from

them. The Minister could not tell me in what capacity I was to go, nor

did he know much about it. He showed me the original of the Emperor's

letter, which was remarkable for its brevity. It ran almost as follows

Having but a few days

left to make my arrangements, it was natural that I should think first

of all of your sisters. I asked and obtained from the Emperor admission

for them into the educational establishment founded for daughters of

members of the Legion of Honour at Ecouen, and then under the control of

Madame Campan, their former schoolmistress at St. Germain. Our

separation, as you will easily believe, was very painful; they thought

of nothing but the fresh dangers to which I was to be exposed.

Before proceeding, I must

go hack a little to mention a circumstance that I had omitted. Some

friends, placed by their rank near the person of Joseph Bonaparte, King

of Naples, who was in command of an army in that country, represented to

him that I might he of great service, as I had fought there some years

previously. He had on several occasions testified goodwill towards me,

and it was suggested that he should ask the Emperor for my services. The

latter, commanding the Grand Army in the North of Germany, had, I

believe, established his headquarters at Osterode during the siege of

l)antzic, which followed the bloody Battle of Eylau, where both sides

claimed the victory, although the best and most impartial judges on our

side considered it more than doubtful. The Emperor consented, and caused

orders to be sent inc by General Count Dejean, who was temporarily

holding the office of War Minister, to go at once to Naples, and place

myself at the disposal of his brother. This was not a military order

for, contrary to the usual forms, no letter of service was sent to me.

It was therefore clear that King Joseph was at liberty to employ me as

he pleased, either with the Neapolitan troops or as a civilian for the

Imperial Generals in the Army of Naples have alone the right of

commanding French troops with their letters of service.

My blood boils even now,

and my gorge rises, as I write these lines, to think of what a degree of

abasement I should have sunk to had I been desired to command Neapolitan

soldiers! I, who had fought and annihilated them at Civita.Castellana,

at Otricoli ----who had completely finished them at Calvi, although on

all these occasions we were less than one against twelve or fifteen I,

who had been witness of their cowardice, their desertion, and their

flight

I, who had invaded their

territory but a few days later! I say no more, and return to my

departure for the Army of Italy in 1809. |