| There have been Kerrs or

Kers (the older spelling) in the Borders since the end of the twelfth

century and possibly earlier. The origins of the family have long been

the subject of argument, along with the meaning of the name itself. The

principal theories are:

1. A Norwegian origin: "Kjarr"

signifying a "copse" or "small wood".

2. An ancient British origin: "Caer" is the Welsh for

"fort", found in Carlisle and in several S.W. Scottish

place-names, e.g. Caerlaverock.

3. A Gaelic origin, from the word for "left-handed". (Céarr).

The Gaelic theory may safely be

discarded as the language was never spoken in Kerr territory, and the

Gaelic word for "left-handed" most probably derives from the

well-known family trait (see p. 36). The British theory is just

credible, as Welsh was spoken in Upper Tweeddale, where the family first

surfaced in Scotland, until late in the eleventh century or early in the

twelfth: further west, it survived even later, and the Wallaces of

Elderslie, taking their name from the language, may have spoken it until

just before the Wars of Independence (1296-1328). But family tradition

is firmly in favour of the Norse theory, which is supported by the

presence of "Kjaers" and "Kjarrs" in the area around

Stavanger (our original home) as well as Karrs near St Malo and Carrs in

mid-Lancashire (the next two stages on our journey to the Borders).

According to this theory, our

remote forebears left Southern Norway with RoIf the Ganger — or Rollo

the Walker — thus called because he was too tall and long-legged to

ride, and therefore strode ahead of his berserkers on their ponies. They

settled in the angle of Brittany and the Cherbourg peninsula in 911,

then came to England in 1066 in the retinue of de Bruys, the ancestor of

the Bruces. He took up land near Preston and they received their small

share of it as his gamekeepers, an occupation also followed by John Ker

of Stobo four generations later (the "Hunter of Swynhope" and

the first recorded Scotsman to bear our name; he is mentioned as taking

part in a rough-and-ready land survey, or "perambulation", in

1190). One of his sons held land at Eliston in 1230 or thereabouts, and

other members of the family are recorded in Selkirkshire a generation or

two later, among them Nicol Kerr, who signed the Ragman Roll (a list of

Scottish landowners doing homage to Edward I) in 1296. From the

fourteenth century onwards Kerrs, variously spelt, are numerous in the

Borders, holding land at Altonburn, Crailing, Kersheugh (less than a

mile from Ferniehirst) and several other places, one of them being

Sheriff of Roxburgh towards the end of the fourteenth century, while

others are found in Ayrshire, Stirlingshire and elsewhere.

Jedforest (the upper valley of the Jed)

became Kerr property in 1457 when Andrew Kerr, the originator of our

left-handed tradition (see p. 36) obtained it from the Earl of Angus in

return for becoming the Earl’s "man" or vassal. Ferniehirst,

or rather the ground on which it stands, already seems to have belonged

to another Kerr, Thomas of Kersheugh, whose daughter and heiress,

Margaret, married her kinsman Thomas Kerr of Smailholm, younger son of

Andrew Kerr, mentioned above. From then on the younger Thomas (of

Smailholm) described himself as "of Ferniehirst". He was

knighted and built the original Ferniehirst Castle (most probably on or

near the site of an earlier "peel tower") in or about 1470: it

was destroyed and rebuilt several times but the present castle, dating

from the end of the sixteenth century, incorporates some of the original

structure and much of the original stone.

A dispute as to seniority between the two

main branches of the family, Ferniehirst and Cessford, began about this

time. It occasionally degenerated into a feud, but did not prevent quite

frequent intermarriage. It is difficult to be Impartial about this, but

the following points should be borne in mind:

1. While Sir Thomas Kerr of Ferniehirst

was the younger brother of Walter Ker of Cessford, he inherited the

land, on which he built the castle, through his marriage to Margaret Ker

of Kersheugh and Ferniehirst. Their son "Dand" Kerr (see

below) thus continued the Kersheugh line, and the family had in fact

been established at Kersheugh longer than at Cessford.

2. In any event, the Cessford line ended

with two daughters, one of whom married the head of the Ferniehirst

Kerrs. The Duke of Roxburghe, heir to the Cessford Kers, is descended

from the younger daughter and bears the double-barrelled surname of

Innes-Ker, The first Ker to own the former lands of Kelso Abbey was

Robert Ker of Cessford who was strongly attached to King James VI and

was knighted by him. He was a Gentleman of the Bedchamber and

accompanied James on his journey south to be crowned James I of England.

He was created Lord Ker of Cessford and Earl of Roxburgh in 1616 with

remainder to his heirs male. By his first wife he had but one son who

died young and two daughters, the elder of whom married the 2nd Earl of

Perth. By his second marriage he had another son, Harry Lord Ker, who

also pre-deceased his father leaving three daughters, one married to Sir

William Drummond, another to the Earl of Wigtoun and the youngest to Sir

James Innes of that Ilk, 3rd Baronet.

Sir Thomas Kerr of Ferniehirst (and

originally of Smailholm) is mainly known to history through his

involvement in several lawsuits. He died before his wife, the heiress of

Kersheugh and Ferniehirst, and was the father of Sir Andrew (‘Dand’)

Kerr of Ferniehirst (see below) as well as Thomas Kerr, Abbot of Kelso

and several other children.

"Dand" Kerr (1470-1545)

was one of the great Border "characters" of his time, with a

long and turbulent career. At one stage he was fined and imprisoned,

though the offence is not known, but only the fact that this fine was

later remitted. He acquired, in two stages, the lands and Barony of

Oxnam, and thus qualified to sit in the Scottish Parliament held a few

days before the battle of Flodden. Though the battle, taken as a whole,

was one of the worst disasters ever suffered by Scotland, the Borderers

won their share of it, but the King was dead and the greater part of his

army slaughtered before they returned to the scene. Lord Home, their

leader, then brought what was left of it back to Edinburgh: "Dand",

who had been involved in the successful part of the action, seized Kelso

Abbey the same evening and installed his brother Thomas as Abbot. This

was widely seen as a piece of shameless nepotism, but it is likely

enough that if Sir Andrew and his brother had not got there first,

someone else would — most probably the English.

A few years later, one of Sir Andrew’s

friends fought a pitched battle, "The Raid of Jedwood Forest"

with his kinsman, Walter Ker of Cessford, who was then Warden of the

Middle March — the issue being "Dand’s" right to hold

court in the Forest, and thus to profit from any fines levied there. In

1523 his castle, Ferniehirst, was taken by a large English force under

the Earl of Surrey (the victor of Flodden) and Lord Dacre; but several

hundred of Dacre’s horses were stampeded at night by the Kerr women.

"Dand" continued to hold the Ferniehirst title, acquired other

lands to make up for his loss and took his turn as Warden of the Middle

March and Provost of Jedburgh, as did several of his descendants. The

Wardenship generally alternated between Ferniehirst and Cessford, until

it was abolished by James VI following the Union of the Crowns; the

Provostship was held by Ferniehirst or by members of other local

families: at the last Border Battle, commemorated in the annual

Redeswire Ride and ceremony on the first Saturday in July, Ferniehirst

was Warden (but represented by his Depute) and Rutherford was Provost:

the Warden on the other side was Sir John Forster, already 75, who died

aged over 100, a few months before his Queen.

Ferniehirst was recaptured in 1548, a few

years after Dand’s death, by his son Sir John Kerr, with some

assistance from a French "task force" under the Sieur d’Esse.

The English governor of the castle and his men had committed unspeakable

atrocities in the neighbourhood, and many tried to save themselves by

surrendering to the French rather than the Scots, but the latter, after

slaughtering their own prisoners, "bought" the others from

their allies, trading in valuable horses and weapons for the purpose,

and killed them as well, afterwards playing handball with the Englishmen’s

severed heads. This is commemorated by the annual "Ba’

Game", in which the leather "ba’ " represents an

Englishman’s head and streamers attached to it at the start — but

soon lost in the general scramble — are supposed to be the Englishman’s

hair. It is further commemorated by the Ferniehirst Ride and ceremony,

the centre-piece of the Jethart Festival. Sir John later sat in the

Scottish Parliament and was one of the authors of a letter urging

Elizabeth of England to marry the Earl of Arran. (Many other suitors

were put forward, by various interests: they included the King of Spain

and several French princes, but she preferred to keep them all guessing

and to rule her own kingdom without anyone else telling her what to do.)

Sir John’s brother Robert of Ancram, was the ancestor of the Earls of

Ancram and of the Marquesses of Lothian (see p. 29), to whom the

Ferniehirst title passed when the direct line of descent from Sir John

died out in the seventeenth century.

Sir

John’s son, Sir Thomas Kerr of Ferniehirst, was noted for his loyalty

to Mary Queen of Scots, for whom he built a fortified house in the

centre of Jedburgh. He raised the Royal Standard for her in Dumfries,

helping her and her husband Darnley to put down an insurrection by a

group of her nobles (she won at the time but was forced into exile a few

years later). Subsequently he sheltered her English supporters after the

rising of the Northern Earls (1568) and rescued Lady Northumberland,

stranded by illness in a Liddesdale outlaw’s hide-out. He helped his

father-in-law, Kirkcaldy of Grange, to defend Edinburgh Castle in the

Queen’s name; when it was taken he lost precious family documents

which were never seen again, but at least he escaped with his life

(Kirkcaldy was beheaded) and fled abroad for some years. He was

re-instated in his lands by James VI when the young King came of age and

took power into his own hands. The townsmen of Jedburgh supported the

Regent Morton (later also beheaded) against Mary; they

"debagged" and publicly caned a herald sent out by Ferniehirst

to read out a proclamation of loyalty to the Queen, also compelling him

to eat his document. Sir

John’s son, Sir Thomas Kerr of Ferniehirst, was noted for his loyalty

to Mary Queen of Scots, for whom he built a fortified house in the

centre of Jedburgh. He raised the Royal Standard for her in Dumfries,

helping her and her husband Darnley to put down an insurrection by a

group of her nobles (she won at the time but was forced into exile a few

years later). Subsequently he sheltered her English supporters after the

rising of the Northern Earls (1568) and rescued Lady Northumberland,

stranded by illness in a Liddesdale outlaw’s hide-out. He helped his

father-in-law, Kirkcaldy of Grange, to defend Edinburgh Castle in the

Queen’s name; when it was taken he lost precious family documents

which were never seen again, but at least he escaped with his life

(Kirkcaldy was beheaded) and fled abroad for some years. He was

re-instated in his lands by James VI when the young King came of age and

took power into his own hands. The townsmen of Jedburgh supported the

Regent Morton (later also beheaded) against Mary; they

"debagged" and publicly caned a herald sent out by Ferniehirst

to read out a proclamation of loyalty to the Queen, also compelling him

to eat his document.

From her English prison, Mary wrote to

Sir Thomas, thanking him for his past services and encouraging him to

keep up his loyalty. She seems to have taken a particular liking to his

young son Andrew, the first Lord Jedburgh, and may have knighted him

while still a child, for she asks in particular to be remembered to

"Sir Andrew".

Briefly imprisoned after the fall of

Edinburgh Castle, Sir Thomas was in exile and unable to perform his

duties as Warden at the time of the last major clash on the Border, the

Raid of Redeswire. This incident developed on one of the "days of

truce" when the Wardens or their deputes met to resolve various

local problems and to exchange or hang wanted criminals. On this

occasion the English Warden complained that the Scots had failed to hand

over a thief known as "Farnstein" (not a German refugee or

mercenary, as one might think, but an Englishman whose real name was

Robson). This led to mutual insults, no doubt aggravated by the fact

that both sides had been liquidating a great deal of liquid. The

argument grew into a scuffle and the scuffle grew into a fight.

Eventually the Jedburgh men arrived in strength and dispersed the

English, killing a few and capturing others, who were later released

without ransom.

Though he missed this particular

incident, Sir Thomas was involved in a similar but smaller affray, on

almost the same spot, ten years later. By then he was back in office as

Warden of the Middle March; Forster, now 84, was still in charge on the

other side, and Forster’s son-in-law, who was also a son of the Earl

of Bedford, was killed. Elizabeth Tudor was not amused, and insisted on

Ferniehirst’s punishment, though the rights and wrongs of the whole

affair were by no means clear. Being anxious to succeed to the English

throne, James VI sought to ingratiate himself with her, and exiled Sir

Thomas to Aberdeen, where he died within a year. The inscription on his

memorial in Jedburgh Abbey reads "Sir THOMAS KERR of Fernyherst,

Warden of the Marches, Provost of Edinburgh and Jedburgh, Father of

Andrew Lord Jedburgh, Sir James Kerr of Creylin (Crailing) and Robert

Earl of Somerset. He died at Aberdeen on March 31, 1586 and lies buried

before the Communion Table. He was a man of action and perfit loyaltie

and constancie to Queen Marie in all her troubles. He suffered 14 years’

banishment besides forfaulter (forfeiture) of his lands. He was restored

to his estates and honours by King James the Sext."

Sir

Thomas married twice. His children by his first wife, Janet Kirkcaldy,

included Sir Andrew of Ferniehirst, first Lord Jedburgh (see below) and

William, who took the name of Kirkcaldy to continue his mother’s line;

his children, however, reverted to Kerr, having failed to inherit the

Grange property. By his second marriage, to Janet Scott, Sir Thomas was

the father of Sir James Kerr of Crailing (father of the second Lord

Jedburgh) and of Robert Can, Earl of Somerset (see below). He had

several other children by both his wives. Sir

Thomas married twice. His children by his first wife, Janet Kirkcaldy,

included Sir Andrew of Ferniehirst, first Lord Jedburgh (see below) and

William, who took the name of Kirkcaldy to continue his mother’s line;

his children, however, reverted to Kerr, having failed to inherit the

Grange property. By his second marriage, to Janet Scott, Sir Thomas was

the father of Sir James Kerr of Crailing (father of the second Lord

Jedburgh) and of Robert Can, Earl of Somerset (see below). He had

several other children by both his wives.

Border warfare having died down after

Redeswire (though there was a final flare-up on the West March, the

"Ill Week" of 1603), Sir Andrew Kerr rebuilt Ferniehirst in

1598. It had been largely destroyed by the English allies of Mary’s

Scottish enemies, following on Sir Thomas’s support for the Northern

Earls in 1569 and a Scottish invasion of the English Middle March in

1570. Despite extensive restoration towards the end of the 19th Century,

the Castle now is essentially Ferniehirst as rebuilt by Sir Andrew,

though some parts (The Chambers and Cellars) date back to 1470 or

thereabouts.

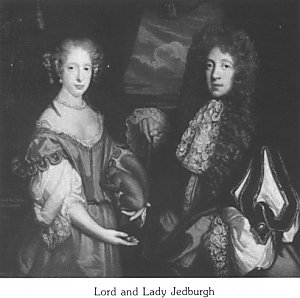

Sir Andrew was Provost of Jedburgh for

many years, but never became Warden, the office having been abolished

following on the Union of the Crowns. He held several Court and

administrative posts, and was created Lord Jedburgh in 1622. His

half-brother Robert Carr (who adopted the English spelling of the name

when he migrated to England with the King) was James’ favourite and

possibly the best-known member of the family to those who have only a

superficial knowledge of English history, and none of Scottish history.

This he achieved by contributing to James’ personal unpopularity in

his new Kingdom, and to the tension that gradually built up against the

Stuarts, culminating in the Civil War and the "execution" of

Charles I. School textbooks, however, have been less than fair to him,

and grossly unfair to James VI and I — a competent ruler of his own

original kingdom even if he did not understand England well enough to be

a real success there, and a man of great intellectual ability.

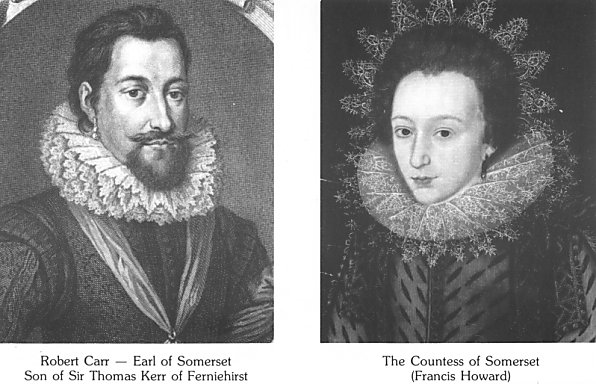

First

a page and then a Groom of the Bedchamber, Robert Can was sent to France

by the King to improve his education. He was injured while dismounting

at a tournament, soon after his return to England; the King ordered him

to be lodged at Court while he recovered and visited him frequently; it

was at this time that he became the royal favourite, rather than

one of several bright young men in the King’s entourage. Thereafter he

accumulated offices and influence, to the great disgust of Englishmen

who felt these good things should have come to them instead. Soon

after being created Earl of Somerset (1613) he married Lady Frances

Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk; but royal favour did not last

much longer, the Somersets being jointly tried for the murder of Sir

Thomas Overbury, sentenced to death, but reprieved and released, then

pardoned within a few years. The evidence against them was by no means

conclusive, and may well have been fabricated by personal enemies. They

had one daughter, Anne, who married Lord Russell, later Earl and then

first Duke of Bedford. First

a page and then a Groom of the Bedchamber, Robert Can was sent to France

by the King to improve his education. He was injured while dismounting

at a tournament, soon after his return to England; the King ordered him

to be lodged at Court while he recovered and visited him frequently; it

was at this time that he became the royal favourite, rather than

one of several bright young men in the King’s entourage. Thereafter he

accumulated offices and influence, to the great disgust of Englishmen

who felt these good things should have come to them instead. Soon

after being created Earl of Somerset (1613) he married Lady Frances

Howard, daughter of the Earl of Suffolk; but royal favour did not last

much longer, the Somersets being jointly tried for the murder of Sir

Thomas Overbury, sentenced to death, but reprieved and released, then

pardoned within a few years. The evidence against them was by no means

conclusive, and may well have been fabricated by personal enemies. They

had one daughter, Anne, who married Lord Russell, later Earl and then

first Duke of Bedford.

The second Lord Jedburgh, as we have

seen, was the half-brother of the, first: his son was the third holder

of the title, which then passed to the Ancram branch of the family,

descended from Robert Ken of Woodhead and Ancrum, second surviving son

of "Dand" Ken. This branch included, in the seventeenth

century, two remarkable men, Robert, first Earl of Ancram (1578-1654)

and his son William, who was created third Earl of Lothian, on his

marriage to the Countess of Lothian in her own right (see p. 30) and

succeeded to the Ancram title on his father’s death. They took

opposite sides in the Civil War, as did the Verneys in England (the

father being a Royalist in both cases) but this did not cause any

personal ill-feeling between them, and they remained close in spite of

politics.

Robert, Earl of Ancram, was the

great-grandson of "Dand" Kerr, grandson of Robert of Woodheid

and Ancram, and son of William Kerr of Woodhead and Ancram, murdered in

1590 by his cousin Cessford (later Earl of Roxburghe), at the

instigation of Lady Cessford, his mother (they had been in dispute about

who should be responsible for the interests of young Andrew Kerr, later

the first Lord Jedburgh; though Sir Andrew had by now come of age, the

bitterness remained). Robert thus became head of his branch of the

family at the age of 12, retaining this position for sixty-five years.

Cessford fled, and had to make ample compensation to Robert before he

could return home. These added resources enabled Robert to spend some

years in study, most probably abroad; he then returned to the Borders

and briefly held the office of Provost of Jedburgh. He followed King

James to England, as did his cousin Robert Carr (later Earl of Somerset)

and took up a post in the household of Henry, Prince of Wales, went

abroad again, then returned to a higher position in Prince Henry’s

household, being simultaneously Captain of the King’s Guard and

spending most of his time in Scotland, where he made various

improvements to Ancrum House, originally built by his grandfather. When

Prince Henry died, Robert was appointed "Gentleman of the

Bedchamber" (senior personal attendant) to Prince Charles,

afterwards Charles I. The Captaincy of the Guard then passed to Andrew

Kerr of Oxnam, son of Sir Andrew Kerr of Ferniehirst, while Robert

returned to England. He was involved in a duel with Charles Maxwell (who

had deliberately picked a quarrel with him in the hope of pleasing the

Duke of Buckingham) and killed his man, for which he was tried at the

Cambridge Assizes and found guilty of manslaughter. King James pardoned

him, however, Maxwell being a known and inveterate troublemaker, but

Prince Charles decided it would be better for him to leave the country

for six months. He was then fully restored to favour, and accompanied

Charles (and Buckingham with whom he must evidently have been

reconciled) on a semi-secret visit to Madrid. The object of the exercise

was to win a Spanish bride for Charles, and they did it in true Spanish

style, serenading the Infanta with their guitars, but to no avail.

Charles probably realised, in due course, that the Spanish marriage

would have been a mistake, not to say a disaster, and did not hold this

failure against his friends; soon afterwards Robert was given part of

the Lothian estates, which had fallen to the King when the second Earl

of Lothian died without sons and heavily in debt: Lothian’s daughter,

who had inherited the title and the rest of the property, later married

Robert’s eldest son William. Charles succeeded his father as King a

few months later and Sir Robert, who had been knighted about 1606,

became one of the most important men at Court though relatively

inconspicuous — being mainly concerned with advising the King on

Scottish affairs and on Court appointments, rather than in helping him

to hold his own against successive Parliaments or govern England without

them.

Sir William having become Earl of Lothian

in 1630, it was inappropriate that the son should be an Earl while his

father was only a knight, and Sir Robert was raised to the same dignity

in 1633, as Earl of Ancram, on the occasion of Charles’ Scottish

coronation. He began to have serious financial problems, however, having

spent a great deal on improvements to Ancrum House before handing it

over to his son, who was now on opposite sides politically, being one of

the leaders of the Covenanting party, who resisted Charles’ attempts

to establish the English form of worship in Scotland. Ancram and Lothian

now seldom met, as the father was now more or less permanently resident

in London and the son in Scotland; one of the rare occasions was in

1643, when Lothian passed through on his way to France, after a

short-lived agreement had been negotiated between the Covenanters and

the King. It did not last long, however, and Charles arrested the

younger Earl on his way back through Oxford; his father then had

considerable trouble in getting him released.

After the judicial murder of Charles I,

Ancram returned to Scotland for some months and then, when there

appeared to be no prospect of a Stuart restoration in the meantime, he

retired to Holland. The House of Lords having been abolished, he could

no longer claim privilege of Parliament against his creditors, and in

any event he did not care to live under the régime that had killed his

King and his friend. He was consoled by frequent visits to and from his

grandsons, Lord Lothian’s sons, who were studying in Leyden while he

spent his last years in Amsterdam; but advised their father to take them

away, as they had learnt all they were likely to learn there, and were

in constant danger of catching "a cruel ague or fever" due to

the damp climate. When Lothian took his advice, however, the loneliness

became too much for him, and he died within a few weeks.

As we have seen, Robert’s son, the

third Earl of Lothian, recombined the Cessford and Ferniehirst lines

through his marriage to the Countess of Lothian. Her great-grandfather,

Mark Ker, of the Cessford branch of the family, had been Abbot of

Newbattle at the Reformation. He followed the new religion and took the

Abbey out of the Church’s hands, becoming its Commendator as did

several other holders of Church property at the time. His son succeeded

him as Commendator and was later created the first Earl of Lothian. The

first Earl was succeeded by his son, but he only left two daughters, the

elder becoming Countess in her own right. However, she got very little

in practice except the title itself. Part of the Lothian estates could

only go to male heirs, and therefore, escheated to the King, who made it

over to Robert Kerr of Ancram, as we have seen, while most of her share

was seized by her late father’s creditors, but redeemed by Ancram, her

father-in-law. The third Earl, her husband, was one of the leaders of

the Covenanting party, but went to London to protest against the "frial"

and judicial murder of the King. He was sent back to Scotland under

escort. His son Robert, the fourth Earl, was one of those who invited

William of Orange to take over the two kingdoms. He was raised to the

rank of Marquis and died a few years before the Treaty of Union which

his eldest son, the second Marquis, strongly supported. Another son,

Lord Mark Kerr, had a long military career (sixty years of actual

service), rising to be a general, as did the 4th Marquis, Lord Mark’s

great-nephew. The title of Lord Jedburgh and the lairdship of

Ferniehirst passed to the fourth Earl of Lothian (later first Marquis)

when the third Lord Jedburgh (sometimes described as second Lord

Jedburgh as his father apparently did not use the title) died childless

in 1692.

Thereafter the "Jedburgh" title was

normally used as a subsidiary title by the Marquis of Lothian, while

that of Earl of Ancram has normally been used, at any given time, by the

Marquis’s heir, often sitting in the House of Commons while his father

sat in the Lords (as is now the case). The sixth Marquis of Lothian,

while Earl of Ancram in his father’s lifetime, lived at Ferniehirst

and is the last recorded member of the family to have done so. Another

Earl of Ancram, who did not live to take up the Lothian title (he was

killed in a shooting accident in Australia, 1895) spent a great deal of

money on restoring Ferniehirst towards the end of the nineteenth

century, and it seems clear that he envisaged living there, but the work

was interrupted on his death. Apart from recent work (see p. 7) the

general appearance of Ferniehirst is very much as he left it.

The sixth Marquis also erected the

Waterloo Monument at Penielheugh, on the ridge between the Teviot and

the Tweed a few miles north of Jedburgh. Bonfires are lit there on

important public and family occasions.

The seventh and eighth Marquesses

both died at a comparatively early age; culling off the promise of

brilliant public careers. Schomberg, ninth Marquis of Lothian, became

Secretary of State for Scotland; his nephew Philip, the eleventh

Marquis, was a member of Milner’s group of talented young

administrators in South Africa after the Boer War; known as the

Kindergarten". He later served as Secretary to Lloyd George and

helped to draft the Treaty of Versailles, and died as British Ambassador

in Washington during World War II. He was succeeded by his cousin, the

12th Marquis (a descendant of the 7th). Peter Lothian and his son

Michael Ancram have both held Ministerial appointments in Conservative

Governments (as did Schomberg, the 9th Marquis, whereas the 11th was a

lifelong Liberal) thus continuing the tradition of public service begun

when Ferniehirst Castle was built. Michael Ancram, at the beginning of

his Political career, is Under-Secretary of State, Scottish Office, and

Lord Lothian, having been Under-Secretary of State, Foreign Office,

ended his career in public service as Lord Warden of the Duchy of

Cornwall for the Prince of Wales.

FOOTNOTES

1 .One of the Ayrshire Kerrs

was a close friend and companion of Sir William Wallace, and was killed trying

to save him from arrest at Robroyston.

2.The most usual spellings in

Scotland are Kerr and Ker, the former acknowledging Lothian as their Chief,

and the others Roxburghe, but Keir, Carr and Carre are other versions of the

name The spelling Can is frequent among English bearers of the name, whether

they came direct from the original "centre of dispersal" near

Preston, or "re-migrated" to Northumbria and other areas from

Scotland. Among well known "re-migrants" are Sir Robert Can (or

Kerr), later Earl of Somerset (see p. 27) and another Sir Robert Can

(with the English spelling only) who helped to capture New Amsterdam from the

Dutch and renamed it New York. There are also three different pronunciations:

the historically correct one, on the basis of Norwegian descent (Kjan) is

identical with "car": it is now mainly used by Englishmen, by the

Scottish aristocracy and by many who emigrated to America, especially those

who went there at an early date. The usual pronunciation in Scotland is

similar to "care". The more usual (but not universal) American

pronunciation is identical with "cur" (a mongrel dog!) and is seldom

heard in Scotland.

3.Some authorities mention 1490

as the date, and Ferniehirst may well have been built in several stages, as

many other castles were.

4.There is some doubt as to

whether the original Ferniehirst was built by Sir Thomas or by his

father-in-law, Thomas Kerr of Kersheugh. It may have been a joint enterprise.

5.The date of his death

is sometimes given as 1524, but D.N.B. and "The Scots on 1545. peerage" agree

6.The rout of Solway Moss

(1542) was arguably even worse. The Scots suffered casualties on much the same

scale as Flodden, mainly drowned rather than killed in action, but also

including a large number of prisoners who had to be ransomed, thus ruining

their families. At Flodden, honour at least was saved, those who were not

slain withdrew in good order, and there were enough of them left to dissuade

the English from launching a full-scale invasion.

7.This is now known as Mary

Queen of Scots’ House, and is one of the principal sights of the town. The

Queen spent some weeks there convalescing from pneumonia, which she had caught

on the long ride to Hermitage Castle, Bothwell’s stronghold near

Newcastleton. While the house was being built (and before her illness) she

stayed at the Spread Eagle in Jedburgh High Street. which is a few months

older.

8.The bothy where she was

concealed belonged to "Jock o’ the Side" who had promised to

protect her against his fellow-outlaws; one of these, however. Black Ormiston,

robbed her as soon as Jock and Northumberland himself were both away.

9. .Sir

Thomas Kerr’s granddaughter, Lady Anne Can, the only daughter of James’

favourite, married a later Earl of Bedford and the subsequent Dukes of Bedford

were descended from her.

10.James VI and I wrote several

books, and was probably the first to guess at a link between smoking (a new

habit, to which he greatly objected) and cancer; this link was only confirmed

by medical research some 350 years later. He gave the impetus to the

translation of the Authorised Version of the Bible, which is dedicated to him,

frequently attended meetings of the committee in charge of this work, and may

have translated several of the Psalms.

11.She had previously been

married to the Earl of Essex, but had obtained a divorce from him on the

grounds that "he was impotent with no woman except her".

12.There

is some disagreement among the authorities as to how the Lords Jedburgh should

be numbered, due to the fact that not all those who were entitled to the title

in fact used it.

13.George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, was James’ favourite after Robert Can; he Was

English, and jealous of the King’s Scottish cronies, and Maxwell evidently

thought the new favourite would do something for him, if he got rid of the old

favourite’s cousin. However, Maxwell was killed in the duel; Buckingham Was

assassinated a few years later, and Ancram outlived them both by a Whole

geneation.

14.Scotland and England were

still two kingdoms, though with only one King (Austria and Hungary had a

similar relationship until 1918). Charles I was therefore crowned King of

England in Westminster Abbey (1625) and King of Scots at Scone. Charles II,

his eldest son, was also crowned at Scone (1650) ten years before his English

coronation. This was the last Scottish coronation as James VII & II did

not feel it safe to come to this country during his brief reign, and James

VIII and Ill (otherwise known as the ‘Old Pretender’) was never crowned,

though he visited Scotland briefly in 1715-16.

15.Incorrectly described as an

"execution" in most history books. It was murder, because the King’s

"trial" was itself illegal. In the first place the King could not

lawfully be "fried" by anyone; secondly if he could have been tried,

the House of Lords would have been the only competent body for that purpose;

thirdly he was "fried" for an "offence" which was

non-existent at the time when he was alleged to have committed it (i.e. making

war on his own people), and finally the "judges" had already decided

the outcome in advance. Those of them who were still alive at the Restoration

were themselves fried and executed for treason.

15a.The 4th Marquis fought in

Cumberland’s army at Culloden. His brother, Lord Robert Kerr, was the only

officer killed on the "Hanoverian" or "English" side at

Culloden.

16.The present Earl, however,

seldom uses his title, and prefers to be known as "Mr" Ancram or

"Michael Ancram", a habit he acquired while practising as an

advocate in the Scottish Courts. Scottish Judges have the title of

"Lord" with their surname or a territorial designation (though they

do not sit in the House of Lords), and it would therefore be confusing for an

advocate to be referred to in the same way during a frial.

17.For those who are unfamiliar

with Scottish administrative arrangements it should be explained that, while

Scotland and England form part of the same State, the United Kingdom of Great

Britain and Northern Ireland, various subjects which in England come under

different Cabinet Ministers (Home Secretary, Secretary of State for Education

and Science, Minister of Housing. Health, etc.) are in Scotland all placed

under the authority of the Scottish Office, headed by the Secretary of State

for Scotland. In the nineteenth century he was often a peer; today he is

always an MP representing a Scottish constituency, assisted by a team of

Junior Ministers, some of whom are MPs while others are peers. But there is,

only one Foreign Secretary and only one Secretary of State for Defence.

18.Robert Earl of Ancram was a

great friend of the poet John Donne who left him his portrait "painted in

shadows" |