|

There was once a man

who got his living by working in the fields. He had one little son,

called Curly-Locks, and one little daughter, called Golden-Tresses;

but his wife was dead, and, as he had to be out all day, these

children were often left alone. So, as he was afraid that some evil

might befall them when there was no one to look after them, he, in

an ill day, married again.

I say, “in an ill day,” for his second wife was a most deceitful

woman, who really hated children, although she pretended, before her

marriage, to love them. And she was so unkind to them, and made the

house so uncomfortable with her bad temper, that her poor husband

often sighed to himself, and wished that he had let well alone, and

remained a widower.

But it was no use crying over spilt milk; the deed was done, and he

had just to try to make the best of it. So things went on for

several years, until the children were beginning to run about the

doors and play by themselves.

Then one day the Goodman chanced to catch a hare, and he brought it

home and gave it to his wife to cook for the dinner.

Now his wife was a very good cook, and she made the hare into a pot

of delicious- soup; but she was also very greedy, and while the soup

was boiling she tasted it, and tasted it, till at last she

discovered that it was almost gone. Then she was in a fine state of

mind, for she knew that her husband would soon be coming home for

his dinner, and that she would have nothing to set before him.

So what do you think the wicked woman did? She went out to the door,

where her little step-son, Curly Locks, was playing in the sun, and

told him to come in and get his face washed. And while she was

washing his face, she struck him on the head with a hammer and

stunned him, and popped him into the pot to make soup for his

father’s dinner.

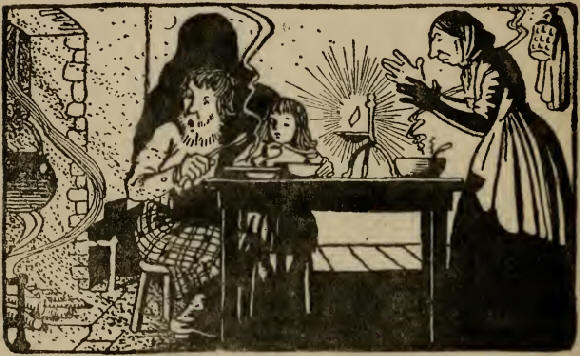

By and by the Goodman came in from his work, and the soup was dished

up; and he, and his wife, and his little daughter, Golden-Tresses,

sat down to sup it.

“Where’s Curly-Locks?” asked the Goodman. “It’s a pity he is not

here as long as the soup is hot.”

“How should I ken?” answered his wife crossly. “I have other work to

do than to run about after a mischievous laddie all the morning.”

The Goodman went on supping his soup in silence for some minutes;

then he lifted up a little foot in his spoon.

“This is Curly-Locks’

foot,” he cried in horror. Thero hath been ill work here.”

“Hoots, havers,” answered his wife, laughing, pretending to be very

much amused. “What should Curly-Locks’ foot be doing in the soup?

’Tis the hare’s forefoot, which is very like that of a bairn.”

But presently the Goodman tooK something else up in his spoon.

“This is Curly-Locks’ hand,” he said shrilly. “I ken it by the crook

in its little finger.”

“The man’s demented,” retorted his wife. “not to ken the hind foot

of a hare when he sees it!”

So the poor father did not say any more, but went away out to his

work, sorely perplexed in his mind; while his little daughter,

Golden-Tresses, who had a shrewd suspicion of what had happened,

gathered all the bones from the empty plates, and, carrying them

away in her apron, buried them beneath a flat stone, close by a

white rose tree that grew by the cottage door.

And, lo and behold! those poor bones, which she buried with such

care:

“Grew and grew,

To 'a milk-white Doo,

That took its wings,

And away it flew.”

And at last it lighted on a tuft of grass by a burnside, where two

women were, washing clothes. It sat there cooing to itself for some

time; then it sang this song softly to them:

“Pew, pew,

My mimmie me slew,

My daddy me chew,

My sister gathered my banes,

And put them between two milk-white stanes.

And I grew and grew

To a milk-white Doo,

And I took to my wings and away I flew.”

The women stopped washing and looked at one another in astonishment.

It was not every day that they ^came across a bird that could sing a

song like that, and they felt that there was something not canny

about it.

“Sing that song again, my bonnie bird,” said one of them at last,

“and we’ll give thee all these clothes!”

So the bird sang its song over again, and the washerwomen gave it

all the clothes, and it tucked them under its right wing, and flew

on.

Presently it came to a house where all the windows were open, and it

perched on one of the window-sills, and inside it saw a man counting

out a great heap of silver.

And, sitting on the window-sill, it sang its song to him:

“Pew, pew,

My mi ramie me slew,

My daddy me chew,

My sister gathered my banes,

And put them between two milk-white stanes.

And I grew and grew

To a milk-white Doo,

And I took to my wings and away I flew.”

The man stopped counting his silver, and listened. He felt, like the

washerwomen, that there was something not canny about this Doo. When

it had finished its song, he said:

“Sing that song again, my bonnie bird, and I’ll give thee a’ this

siller in a bag.”

So the Doo sang its song over again, and got the bag of silver,

which it tucked under its left wing. Then it flew on.

It had not flown very far, however, before it came to a mill where

two millers were grinding corn. And it settled down on a sack of

meal and sang its song to them.

“Pew, pew,

My mimmie me slew,

My daddy me chew,

My sister gathered my banes,

And put them between two milk-white stanea.

And I grew and grew

To a milk-white Doo,

And I took to my wings and away I flew.”

The millers stopped their work, and looked at one another,

scratching their heads in amazement.

“Sing that song over again, my bonnie bird!” exclaimed both of them

together when the Doo had finished, “and we will give thee this

millstone.”

So the Doo repeated its song, and got the millstone, which it asked

one of the millers to lift on its back; then it flew out of the

mill, and up the valley, leaving the two men staring after it dumb

with astonishment.

As you may think, the Milk-White Doo had a heavy load to carry, but

it went bravely on till it came within sight of its father’s

cottage, and lighted down at last on the thatched roof.

Then it laid its burdens on the thatch, and, flying down to the

courtyard, picked up a number of little chuckie stones. With them in

its beak it flew back to the roof, and began to throw them down the

chimney.

By this time it was evening, and the Goodman and his wife, and his

little daughter, Golden-Tresses, were sitting round the table eating

their supper. And you may be sure that they were all very much

startled when the stones came rattling down the chimney, bringing

such a cloud of soot with them that they were like to be smothered.

They all jumped up from their chairs, and ran outside to see what

the matter was.

And Golden-Tresses, being the littlest, ran the fastest, and when

she came out at the door the Milk-White Doo flung the bundle of

clothes down at her feet.

And the father came out next, and the Milk-White Doo flung the bag

of silver down at his feet.

But the wicked step-mother, being somewhat stout, came out last, and

the Milk-White Doo threw the millstone right down on her head and

killed her.

Then it spread its wings and flew away, and has never been seen

again; but it had made the Goodman and his daughter rich for life,

and it had rid them of the cruel stepmother, so that they lived in

peace and plenty for the remainder of their days.

|