|

It was a fine summer

morning, and the Laird o’ Co* was having a dander on the green turf

outside the Castle walls. His real name was the Laird o’ Colzean,

and his descendants to-day bear the proud title of Marquises of

Ailsa, but all up and down Ayrshire nobody called him anything else

than the Laird o’ Co’; because of the Co’s, or caves, which were to

be found in the rock on which his Castle was built.

He was a kind man, and a courteous, always ready to be interested in

the affairs of his poorer neighbours, and willing to listen to any

tale of woe.

So when a little boy came across the green, carrying a small can in

his hand, and, pulling his forelock, asked him if he might go to the

Castle and get a little ale for his sick mother, the Laird gave his

consent at once, and, patting the little fellow on the head, told

him to go to the kitchen and ask for the butler, and tell him that

he, the Laird, had given orders that his can was to be filled with

the best ale that was in the cellar.

Away the boy went, and found the old butler, who, after listening to

his message, took him down into the cellar, and proceeded to carry

out his Master’s orders.

There was one cask of particularly fine ale, which was kept entirely

for the Laird’s own use, which had been opened some time before, and

which was now about half full.

"I will fill the bairn’s can out o’ this,” thought the old man to

himself. “’Tis both nourishing and light—the very thing for sick

folk.” So, taking the can from the child’s hand, he proceeded to

draw the ale.

But what was his astonishment to find that, although the ale flowed

freely enough from the barrel, the little can, which could not have

held more than a quarter of a gallon, remained always just half

full.

The ale poured into it in a clear amber stream, until the big cask

was quite empty, and still the quantity that was in the little can

did not seem to increase.

The butler could not understand it. He looked at the cask,. and then

he looked at the can; then he looked down at the floor at his feet

to see if he had not spilt any.

No, the ale had not disappeared in that way, for the cellar floor

was as white, and dry, and clean, as possible.

“Plague on the can; it must be bewitched,” thought the old man, and

his short, stubby hair stood up like porcupine quills round his bald

head, for if there was anything on earth of which he had a mortal

dread, it was Warlocks, and Witches, and such like Bogles.

“I'm not going to broach another barrel,” he said gruffly, handing

back the half-filled can to the little lad. “So ye may just go home

with what is there; the Laird’s ale is too good to waste on a

smatchet like thee.”

But the boy stoutly held his ground. A promise was a promise, and

the Laird had both promised, and sent orders to the butler that the

can was to be filled, and he would not go home till it was filled.

It was in vain that the old man first argued, and then grew

angry—the boy would not stir a step.

“The Laird had said that he was to get the ale, and the ale he must

have.”

At last the perturbed butler left him standing there, and hurried

of! to his master to tell him he was convinced that the can was

bewitched, for it had swallowed up a whole half cask of ale, and

after doing so it was only half full; and to ask if he would come

down himself, and order the lad off the premises.

“Not I,” said the genial Laird, “for the little fellow is quite

right. I promised that he should have his can full of ale to take

home to his sick mother, and he shall have it if it takes all the

barrels in my cellar to fill it. So haste thee to the house again,

and open another cask". The butler dare not disobey; so he

reluctantly retraced his steps, but, as he went, he shook his head

sadly, for it seemed to him that not only the boy with the can, but

his master also, was bewitched.

When he reached the cellar he found the bairn waiting patiently

where he had left him, and, without wasting further words, he took

the can from his hand and broached another barrel.

If he had been astonished before, he was more astonished now. Scarce

had a couple of drops fallen from the tap, than the can was full to

the brim.

“Take it, laddie, and begone, with all the speed thou canst,” he

said, glad to get the can out of his fingers; and the boy did not

wait for a second bidding. Thanking the butler most earnestly for

his trouble, and paying no attention to the fact that the old man

had not been so civil to him as he might have been, he departed.

Nor, though the butler took pains to ask all round the countryside,

could he ever hear of him again, nor of anyone who knew anything

about him, or anything about his sick mother.

Years passed by, and sore trouble fell upon the House o' Co'. For

the Laird went to fight in the wars in Flanders, and, chancing to be

taken prisoner, he was shut up in prison, and condemned to death.

Alone, in a foreign country, he had no friends to speak for him, and

escape seemed hopeless.

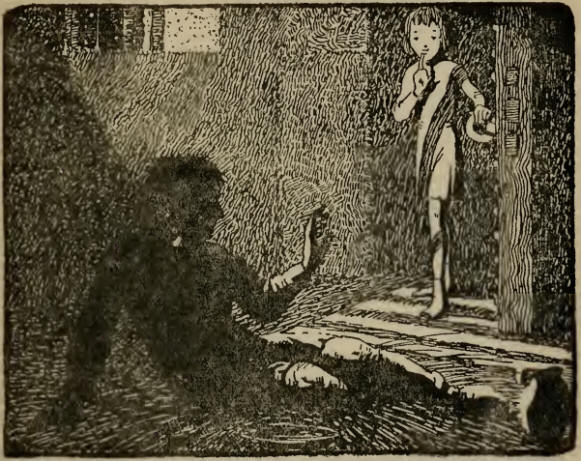

It was the night before his execution, and he was sitting in his

lonely cell, thinking sadly of his wife and children, whom he never

expected to see again. At the thought gf them the picture of his

home rose clearly in his mind the grand old Castle standing on its

rock, and the bonnie daisy-spangled stretch of greensward which lay

before its gates, where he had been wont to take a dander in the

sweet summer mornings. Then, all unbidden, a vision of the little

lad carrying the can, who had come to beg ale for his sick mother,

and whom he had long ago forgotten, rose up before him.

The vision was so clear and distinct that he felt almost as if he

were acting the scene over again, and he rubbed his eyes to get rid

of it, feeling that, if he had to die to-morrow, it was time that he

turned his thoughts to better things.

But as he did so the door of his cell flew noiselessly open, and

there, on the threshold, stood the self-same little lad, looking not

a day older, with his finger on his lip, and a mysterious smile upon

his face.

“Laird o’ Co’,

Rise and go!”

he whispered, beckoning to him to follow him. Needless to say, the

Laird did so, too much amazed to think of asking questions.

Through the long passages of the prison the little lad went, the

Laird close at his heels; and whenever he came to a locked door, he

had but to touch it, and it opened before them, so that in no long

time they were safe outside the walls.

The overjoyed Laird would have overwhelmed his little deliverer with

words of thanks had not the boy held up his hand to stop him. “Get

on my back,” he said shortly, “for thou are not safe till thou art

out of this country.”

The Laird did as he was bid, and, marvellous as it seems, the boy

was quite able to bear his weight. As soon as he was comfortably

seated the pair set off, over sea and land, and never stopped till,

in almost less time than it takes to tell it, the boy set him down,

in the early dawn, on the daisy-spangled green in front of his

Castle, just where he had spoken first to him so many years before.

Then he turned, and laid his little hand on the Laird’s big one:

“Ae gude turn deserves anither, Tak’ ye that for being sae kind to

my auld mither,” he said, and vanished.

And from that day to this he has never been seen again. |