|

About two hundred

years ago there was a poor man working as a labourer on a farm in

Lanarkshire. He was what is known as an “Orra Man”; that is, he had

no special work mapped out for him to do, but he was expected to

undertake odd jobs of any kind that happened to turn up.

One day his master sent him out to cast peats on a piece of moorland

that lay on a certain part of the farm. Now this strip of moorland

ran up at one end to a curiously shaped crag, known as Merlin’s

Crag, because, so the country folk said, that famous Enchanter had

once taken up his abode there.

The man obeyed, and, being a willing fellow, when he arrived at the

moor he set to work with all his might and main. He had lifted quite

a quantity of peat from near the Crag, when he was startled by the

appearance of the very smallest woman that he had ever seen in his

life. She was only about two feet high, and she was dressed in a

green gown and red stockings, and her long yellow hair was not bound

by any ribbon, but hung loosely round her shoulders.

She was such a dainty little creafaire that the astonished

countryman stopped working, stuck his spade into the ground, and

gazed at her in wonder.

His wonder increased when she held up one of her tiny fingers and

addressed him in these words: “What wouldst thou think if I were to

send my husband to uncover thy house? You mortals think that you can

do aught that pleaseth you.”

Then, stamping her tiny foot, she added in a voice of command, “Put

back that turf instantly, or thou shalt rue this day.”

Now the poor man had often heard of the Fairy Folk, and of the harm

that they could work to unthinking mortals who offended them, so in

fear and trembling he set to work to undo all his labour, and to

place every divot in the exact spot from which he had taken it.

When he was finished he looked round for his strange visitor, but

she had vanished completely; he could not tell how, nor where.

Putting up his spade, he wended his way homewards, and going

straight to his master, he told him the whole story, and suggested

that in future the peats should be taken from the other end of the

moor.

But the master only laughed. He was a strong, hearty man, and had no

belief in Ghosts, or Elves, or Fairies, or any other creature that

he could not see; but although he laughed, he was vexed that his

servant should believe in such things, so to cure him, as he

thought, of his superstition, he ordered him to take a horse and

cart and go back at once, and lift all the peats and bring them to

dry in the farm steading.

The poor man obeyed with much reluctance; and was greatly relieved,

as weeks went on, to find that, in spite of his having done so, no

harm befell him.

In fact, he began to think that his master was right, and that the

whole thing must have been a dream.

So matters went smoothly on. Winter passed, and spring, and summer,

until autumn came round once more, and the very day arrived on which

the peats had been lifted the year before.

That day, as the sun went down, the orra man left the farm to go

home to his cottage, and as his master was pleased with him because

he had been working very hard lately, he had given him a little can

of milk as a present to carry home to his wife.

So he was feeling very happy, and as he walked along he was humming

a tune to himself. His road took him by the foot of Merlin's Crag,

and as he approached it he was astonished to find himself growing

strangely tired. His eyelids dropped over his eyes as if he were

going to sleep, and his feet grew as heavy as lead.

“I will sit down and take a rest for a few minutes,” he said to

himself; “the road home never seemed so long as it does to-day."

So he sat down on a tuft of grass right under the shadow of the

Crag, and before he knew where he was he had fallen into a deep and

heavy slumber.

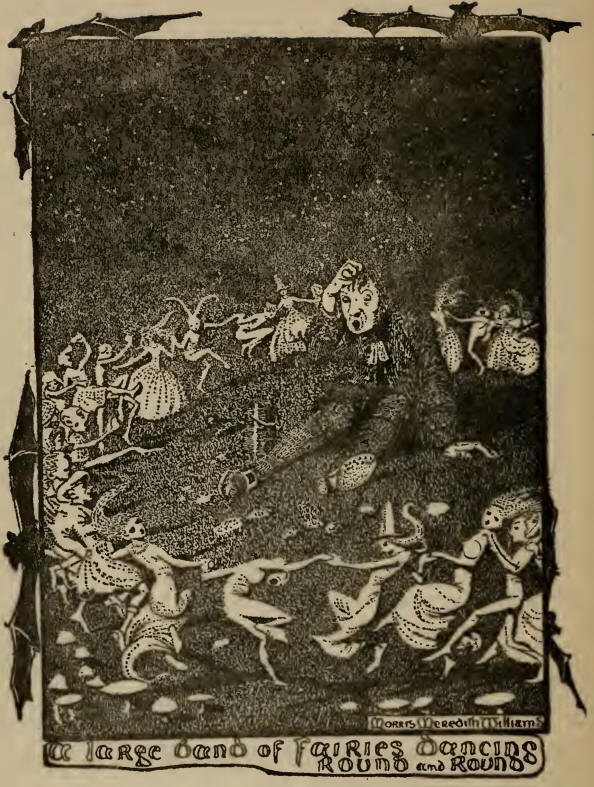

When he awoke it was near midnight, and the moon had risen on the

Crag. And he rubbed his eyes, when by its soft light he became aware

of a large band of Fairies who were dancing round and round him,

singing and laughing, pointing their tiny fingers at him, and

shaking their wee fists in his face.

The bewildered man rose and tried to walk away from them, but turn

in whichever direction he would the Fairies accompanied him,

encircling him in a magic ring, out of which he could in no wise go.

At last they stopped,

and, with shrieks of elfin laughter, led the prettiest and daintiest

of their companions up to him, and cried, “Tread a measure, tread a

measure, Oh, Man! Then wilt thou not be so eager to escape from our

company.”

Now the poor labourer was but a clumsy dancer, and he held back with

a shamefaced air; but the Fairy who had been chosen to be his

partner reached up and seized his hands, and lo! some strange magic

seemed to enter into his veins, for in a moment he found himself

waltzing and whirling, sliding and bowing, as if he had done nothing

else but dance all his life.

And, strangest thing of all! he forgot about his home and his

children; and he felt so happy that he had no longer the slightest

desire to leave the Fairies' company.

All night long the merriment went on. The Little Folk danced and

danced as if they were mad, and the farm man danced with them, until

at last a shrill sound came over the moor. It was the cock from the

farmyard crowing its loudest to welcome the dawn.

In an instant the revelry ceased, and the Fairies, with cries of

alarm, crowded together and rushed towards the Crag, dragging the

countryman along in their midst. As they reached the rock, a

mysterious door, which he never remembered having seen before,

opened in it of its own accord, and shut again with a crash as soon

as the Fairy Host had all trooped through.

The door led into a large, dimly lighted hall full of tiny couches,

and here the Little Folk sank to rest, tired out with their

exertions, while the good man sat down on a piece of rock in the

corner, wondering what would happen next.

But there seemed to be some kind of spell thrown over his senses,

for even when the Fairies awoke and began to go about their

household occupations, and to carry out certain curious practices

which he had never seen before, and which, as you will hear, he was

forbidden to speak of afterwards, he was content to sit and watch

them, without in any way attempting to escape.

As it drew toward evening someone touched his elbow, and he turned

round with a start to see the little woman with the green dress and

scarlet stockings, who had remonstrated with him for lifting the

turf the year before, standing by his side.

“The divots which thou took'st from the roof of my house have grown

once more,” she said, “and once more it is covered with grass; so

thou canst go home again, for justice is satisfied—thy punishment

hath lasted long enough. But first must thou take thy solemn oath

never to tell to mortal ears what thou hast seen whilst thou hast

dwelt among us.”

The countryman promised gladly, and took the oath with all due

solemnity. Then the door was opened, and he was at liberty to

depart.

His can of milk was standing on the green, just where he had laid it

down when he went to sleep; and it seemed to him as if it were only

yesternight that the farmer had given it to him.

But when he reached his home he was speedily undeceived. For his

wife looked at him as if he were a ghost, and the children whom he

had left wee, toddling things were now well-grown boys and girls,

who stared at him as if he had been an utter stranger.

“Where hast thou been these long, long years?” cried his wife when

she had gathered her wits and seen that it was really he, and not a

spirit. “And how couldst thou find it in thy heart to leave the

bairns and me alone?”

And then he knew that the one day he had passed in Fairy-land had

lasted seven whole years, and he realised how heavy the punishment

had been which the Wee Folk had laid upon him.

|