|

In byegone days, in

an old farmhouse which stood by a river, there lived a beautiful

girl called Maisie. She was tall and straight, with auburn hair and

blue eyes, and she was the prettiest girl in all the valley. And one

would have thought that she would have been the pride of her

mother's heart.

But, instead of this, her mother used to sigh and shake her head

whenever she looked at her. And why?

Because, in those days, all men were sensible; and instead of

looking out for pretty girls to be their wives, they looked out for

girls who could cook and spin, and who gave promise of becoming

notable housewives.

Maisie’s mother had been an industrious spinster; but, alas! to her

sore grief and disappointment, her daughter did not take after her.

The girl loved to be out of doors, chasing butterflies and plucking

wild flowers, far better than sitting at her spinning-wheel. So when

her mother saw one after another of Maisie’s companions, who were

not nearly so pretty as she was, getting rich husbands, she sighed

and said:

“Woe’s me, child, for methinks no brave wooer will ever pause at our

door while they see thee so idle and thoughtless.” But Maisie only

laughed.

At last her mother grew really angry, and one bright Spring morning

she laid down three heads of lint on the table, saying sharply, “I

will have no more of this dallying. People will say that it is my

blame that no wooer comes to seek thee. I cannot have thee left on

my hands to be laughed at, as the idle maid who would not marry. So

now thou must work; and if thou hast not these heads of lint spun

into seven hanks of thread in three days, I will e’en speak to the

Mother at St. Mary’s Convent, and thou wilt,go there and learn to be

a nun.”

Now, though Maisie was an idle girl, she had no wish to be shut up

in a nunnery; so she tried not to think of the sunshine outside, but

sat down soberly with her distaff.

But, alas! she was so little accustomed to work that she made but

slow progress; and although she sat at the spinning-wheel all day,

and never once went out of doors, she found at night that she had

only spun half a hank of yarn.

The next day it was even worse, for her arms ached so much she could

only work very slowly. That night she cried herself to sleep; and

next morning, seeing that it was quite hopeless to expect to get her

task finished, she threw down her distaff in despair, and ran out of

doors.

Near the house was a deep dell, through which ran a tiny stream.

Maisie loved this dell, the flowers grew so abundantly there.

This morning she ran down to the edge of the stream, and seated

herself on a large stone. It was a glorious morning, the hazel trees

were newly covered with leaves, and the branches nodded over her

head, and showed like delicate tracery against the blue sky. The

primroses and sweet-scented violets peeped out from among the grass,

and a little water wagtail came and perched on a stone in the middle

of the stream, and bobbed up and down, till it seemed as if he were

nodding to Maisie, and as if he were trying to say to her, “Never

mind, cheer up.”

But the poor girl was in no mood that morning to enjoy the flowers

and the birds. Instead of watching them, as she generally did, she

hid her face in her hands, and wondered what would become of her.

She rocked herself to and fro, as she thought how terrible it would

be if her mother fulfilled her threat and shut her up in the Convent

of St. Mary, with the grave, solemn-faced sisters, who seemed as if

they had completely forgotten what it was like to be young, and run

about in the sunshine, and laugh, and pick the fresh Spring flowers.

“Oh, I could not do it, I could not do it,” she cried at last. “It

would kill me to be a nun.”

“And who wants to make a pretty wench like thee into a nun?” asked a

queer, cracked voice quite close to her.

Maisie jumped up, and

stood staring in front of her as if she had been moonstruck. For,

just across the stream from where she had been sitting, there was a

curious boulder, with a round hole in the middle of it for all the

world like a big apple with the core taken out.

Maisie knew it well; she had often sat upon it, and wondered how the

funny hole came to be there.

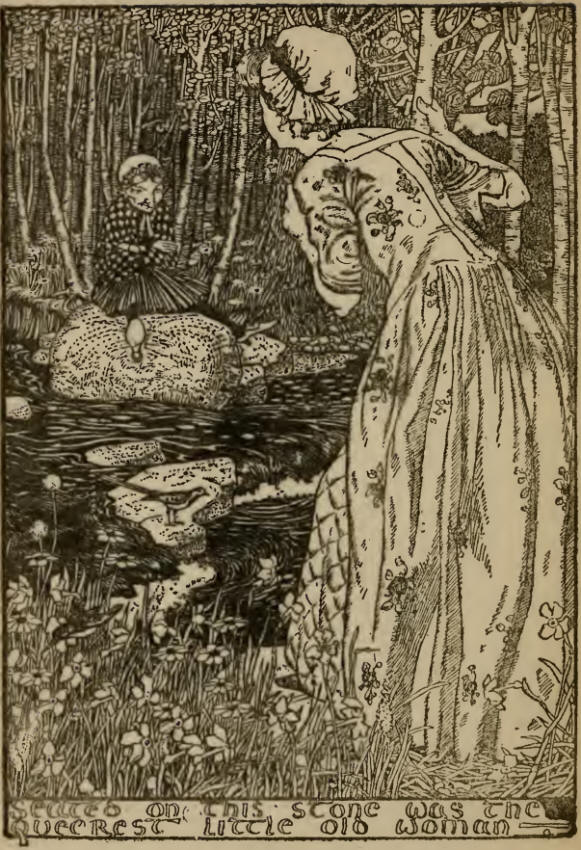

It was no wonder that she stared, for, seated on this stone, was the

queerest little old woman that she had ever seen in her life.

Indeed, had it not been for her silver hair, and the white mutch

with the big frill that she wore on her head, Maisie would have

taken her for a little girl, she wore such a very short skirt, only

reaching down to her knees.

Her face, inside the frill of her cap, was round, and her cheeks

were rosy, and she had little black eyes, which twinkled merrily as

she looked at the startled maiden. On her shoulders was a black and

white checked shawl, and on her legs, which shedangled over the edge

of the boulder, she wore black silk stockings and the neatest little

shoes, with great silver buckles.

In fact, she would have been quite a pretty old lady had it not been

for her lips, which were very long and very thick, and made her look

quite ugly in spite of her rosy cheeks and black eyes. Maisie stood

and looked at her for such a long time in silence that she repeated

her question.

“And who wants to make a pretty wench like thee into a nun? More

likely that some gallant gentleman should want to make a bride of

thee.”

“Oh, no,” answered Maisie, “my mother says no gentleman would look

at me because I cannot spin.”

“Nonsense,” said the tiny woman. “Spinning is all very well for old

folks like me — my lips, as thou seest, are long and ugly because I

have spun so much, for I always wet my fingers with them, the easier

to draw the thread from the distaff. No, no, take care of thy

beauty, child; do not waste it over the spinning-wheel, nor yet in a

nunnery.”

“If my mother only thought as thou dost,” replied the girl sadly;

and, encouraged by the old woman’s kindly face, she told her the

whole story.

“Well,” said the old Dame, “I do not like to see pretty girls weep;

what if I were able to help thee, and spin the lint for thee?”

Maisie thought that this offer was too good to be true; but her new

friend bade her run home and fetch the lint; and I need not tell you

that she required no second bidding.

When she returned she handed the bundle to the little lady, and was

about to ask her where she should meet her in order to get the

thread from her when it was spun, when a sudden noise behind her

made her look round.

She saw nothing; but what was her horror and surprise? when she

turned back again, to find that the old woman had vanished entirely,

lint and all.

She rubbed her eyes, and looked all round, but she was nowhere to be

seen. The girl was utterly bewildered. She wondered if she could

have been dreaming, but no that could not be, there were her

footprints leading up the bank and down again, where she had gone

for the lint, and brought it back, and there was the mark of her

foot, wet with dew, on a stone in the middle of the stream, where

she had stood when she had handed the lint up to the mysterious

little stranger.

What was she to do now? What would her mother say when, in addition

to not having finished the task that had been given her, she had to

confess to having lost the greater part of the lint also? She ran up

and down the little dell, hunting amongst the bushes, and peeping

into every nook and cranny of the bank where the little old woman

might have hidden herself. It was all in vain; and at last, tired

out with the search, she sat down on the stone once more, and

presently fell fast asleep.

When she awoke it was evening. The sun had set, and the yellow glow

on the western horizon was fast giving place to the silvery light of

the moon. She was sitting thinking of the curious events of the day,

and gazing at the great boulder opposite, when it seemed to her as

if a distant murmur of voices came from it.

With one bound she crossed the stream, and clambered on to the

stone. She was right.

Someone was talking underneath it, far down in the ground. She put

her ear close to the stone, and listened.

The voice of the queer little old woman came up through the hole.

"Ho, ho, my pretty little wench little knows that my name is

Habetrot.”

Full of curiosity, Maisie put her eye to the opening, and the

strangest sight that she had ever seen met her gaze. She seemed to

be looking through a telescope into a wonderful little valley. The

trees there were brighter and greener than any that she had ever

seen before and there were beautiful flowers, quite different from

the flowers that grew in her country. The little valley was carpeted

with the most exquisite moss, and up and down it walked her tiny

friend, busily engaged in spinning.

She was not alone, for round her were a circle of other little old

women, who were seated on large white stones and they were all

spinning away as fast as they could.

Occasionally one would look up, and then Maisie saw that they all

seemed to have the same long, thick lips that her friend had. She

really felt very sorry, as they all looked exceedingly kind, and

might have been pretty had it not been for this defect.

One of the Spinstresses sat by herself, and was engaged in winding

the thread, which the others had spun, into hanks. Maisie did not

think that this little lady looked so nice as the others. She was

dressed entirely in grey, and had a big hooked nose, and great horn

spectacles. She seemed to be called Slantlie Mab, for Maisie heard

Habetrot address her by that name, telling her to make haste and tie

up all the thread, for it was getting late, and it was time that the

young girl had it to carry home to her mother.

Maisie did not quite know what to do, or how she was to get the

thread, for she did not like to shout down the hole in case the

queer little old woman should be angry at being watched.

However, Habetrot, as she had called herself, suddenly appeared on

the path beside her, with the hanks of thread in her hand.

“Oh, thank you, thank you,” cried Maisie. “What can I do to show you

how thankful I am?”

“Nothing,” answered the Fairy. “For I do not work for reward. Only

do not tell your mother who span the thread for thee.”

It was now late, and Maisie lost no time in running home with the

precious thread upon her shoulder. When she walked into the kitchen

she found that her mother had gone to bed. She seemed to have had a

busy day, for there, hanging up in the wide chimney, in order to

dry, were seven large black puddings.

The fire was low, but bright and clear; and the sight of it and the

sight of the puddings suggested to Maisie that she was very hungry,

and that fried black puddings were very good.

Flinging the thread down on the table, she hastily pulled off her

shoes, so as not to make a noise and awake her mother; and, getting

down the frying-pan from the wall, she took one of the black

puddings from the chimney, and fried it, and ate it.

Still she felt hungry, so she took another, and then another, till

they were all gone. Then she crept upstairs to her little bed and

fell fast asleep.

Next morning her mother came downstairs before Maisie was awake. In

fact, she had not been able to sleep much for thinking of her

daughter’s careless ways, and had been sorrowfully making up her

mind that she must lose no time in speaking to the Abbess of St.

Mary’s about this idle girl of hers.

What was her surprise to see on the table the seven beautiful hanks

of thread, while, on going to the chimney to take down a black

pudding to fry for breakfast, she found that every one of them had

been eaten. She did did not know whether to laugh for joy that her

daughter had been so industrious, or to cry for vexation because all

her lovely black puddings—which she had expected would last for a

week at least—were gone. In her bewilderment she sang out:

“My daughter’s spun se’en, se’en, se’en,

My daughter’s eaten se’en, se’en, se’en,

And all before daylight.”

Now I forgot to tell you that, about half a mile from where the old

farmhouse stood, there was a beautiful Castle, where a very rich

young nobleman lived. He was both good and brave, as well as rich;

and all the mothers who had pretty daughters used to wish that he

would come their way, some day, and fall in love with one of them.

But he had never done so, and everyone said, “He is too grand to

marry any country girl. One day he will go away to London Town and

marry a Duke’s daughter.”

Well, this fine spring morning it chanced that this young nobleman’s

favourite horse had lost a shoe, and he was so afraid that any of

the grooms might ride it along the hard road, and not on the soft

grass at the side, that he said that he would take it to the smithy

himself.

So it happened that he was riding along by Maisie’s garden gate as

her mother came into the garden singing these strange lines.

He stopped his horse, and said good-naturedly, “Good day, Madam; and

may I ask why you sing such a strange song?”

Maisie’s mother made no answer, but turned and walked into the

house; and the young nobleman, being very anxious to know what it

all meant, hung his bridle over the garden gate, and followed her.

She pointed to the seven hanks of thread lying on the table, and

said, “This hath my daughter done before breakfast.”

Then the young man asked to see the Maiden who was so industrious,

and her mother went and pulled Maisie from behind the door, where

she had hidden herself when the stranger came in; for she had come

downstairs while her mother was in the garden.

She looked so lovely in her fresh morning gown of blue gingham, with

her auburn hair curling softly round her brow, and her face all over

blushes at the sight of such a gallant young man, that he quite lost

his heart, and fell in love with her on the spot.

“Ah,” said he, “my dear mother always told me to try and find a wife

who was both pretty and useful, and I have succeeded beyond my

expectations. Do not let our marriage, I pray thee, good Dame, be

too long deferred.”

Maisie's mother was overjoyed, as you may imagine, at this piece of

unexpected good fortune, and busied herself in getting everything

ready for the wedding; but Maisie herself was a little perplexed.

She was afraid that she would be expected to spin a great deal when

she was married and lived at the Castle, and if that were so, her

husband was sure to find out that she was not really such a good

spinstress as he thought she was.

In her trouble she went down, the night before her wedding, to the

great boulder by the stream in the glen, and, climbing up on it, she

laid her head against the stone, and called softly down the hole,

“Habetrot, dear Habe-trot.”

The little old woman soon appeared, and, with twinkling eyes, asked

her what was troubling her so much just when she should have been so

happy. And Maisie told her.

“Trouble not thy pretty head about that,” answered the Fairy, “but

come here with thy bridegroom next week, when the moon is full, and

I warrant that he will never ask thee to sit at a spinning-wheel

again.”

Accordingly, after all the wedding festivities were over and the

couple had settled down at the Castle, on the appointed evening

Maisie suggested to her husband that they should take a walk

together in the moonlight.

She was very anxious to see what the little Fairy would do to help

her; for that very day he had been showing her all over her new

home, and he had pointed out to her the beautiful new spinning-wheel

made of ebony, which had belonged to his mother, saying proudly,

“To-morrow, little one, I shall bring some lint from the town, and

then the maids will see what clever little fingers my wife has.”

Maisie had blushed as red as a rose as she bent over the lovely

wheel, and then felt quite sick, as she wondered whatever she would

do if Habetrot did not help her.

So on this particular evening, after they had walked in the garden,

she said that she should like to go down to the little dell and see

how the stream looked by moonlight. So to the dell they went.

As soon as they came to the boulder Maisie put her head against it

and whispered, “Habetrot, dear Habetrot" and in an instant the

little old woman appeared.

She bowed in a stately way, as if they were both strangers to her,

and said, “Welcome, Sir and Madam, to the Spinsters' Dell.” And then

she tapped on the root of a great oak tree with a tiny wand which

she held in her hand, and a green door, which Maisie never

remembered having noticed before, flew open, and they followed the

Fairy through it into the other valley which Maisie had seen through

the hole in the great stone.

All the little old women were sitting on their white chucky stones

busy at work, only they seemed far uglier than they had seemed at

first; and Maisie noticed that the reason for this was, that,

instead of wearing red skirts and White mutches as they had done

before, they now wore caps and dresses of dull grey, and instead of

looking happy, they all seemed to be trying to see who could look

most miserable, and who could push out their long lips furthest, as

they wet their fingers to draw the thread from their distaffs.

“Save us and help us! What a lot of hideous old witches,” exclaimed

her husband. "Whatever could this funny old woman mean by bringing a

pretty child like thee to look at them? Thou wilt dream of them for

a week and a day. Just look at their lips”; and, pushing Maisie

behind him, he went up to one of them and asked her what had made

her mouth grow so ugly.

She tried to tell him, but all the sound that he could hear was

something that sounded like SPIN-N-N.

He asked another one, and her answer sounded like this: SPAN-N-N. He

tried a third, and hers sounded like SPUN-N-N.

He seized Maisie by the hand and hurried her through the green door.

“By my troth" he said, “my mother’s spinning-wheel may turn to gold

ere I let thee touch it, if this is what spinning leads to. Rather

than that thy pretty face should be spoilt, the linen chests at the

Castle may get empty, and remain so for ever!”

So it came to pass that Maisie could be out of doors all day

wandering about with her husband, and laughing and singing to her

heart's content. And whenever there was lint at the Castle to be

spun, it was carried down to the big boulder in the dell and left

there, and Habetrot and her companions spun it, and there was no

more trouble about the matter.

|