In bygone days there lived a little

Princess named Gold-Tree, and she was one of the prettiest children

in the whole world.

Although her mother was dead, she had a very happy life, for her

father loved her dearly, and thought that nothing was too much

trouble so long as it gave his little daughter pleasure. But by and

by he married again, and then the little Princess’s sorrows began.

For his new wife, whose name, curious to say, was Silver-Tree, was

very beautiful, but she was also very jealous, and she made herself

quite miserable for fear that, some day, she should meet someone who

was better looking than she was herself.

When she found that her step-daughter was so very pretty, she took a

dislike to her at once, and was always looking at her and wondering

if people would think her prettier than she was. And because, in her

heart of hearts, she was afraid that they would do so, she was very

unkind indeed to the poor girl.

At last, one day, when Princess Gold-Tree was quite grown up, the

two ladies went for a walk to a little well which lay, all

surrounded by trees, in the middle of a deep glen.

Now the water in this well was so clear that everyone who looked

into it saw his face reflected on the surface; and the proud Queen

loved to come and peep into its depths, so that she could see her

own picture mirrored in the water.

But £o-day, as she was looking in, what should she see but a little

trout, which was swimming quietly backwards and forwards not very

far from the surface.

“Troutie, troutie, answer me this one question,” said the Queen. “Am

not I the most beautiful woman in the world?”

“No, indeed, you are not," replied the trout promptly, jumping out

of the water, as he spoke, in order to swallow a fly.

“Who is the most beautiful woman, then?” asked the disappointed

Queen, for she had expected a far different answer.

“Thy step-daughter, the Princess Gold-Tree, without a doubt,” said

the little fish ; then, frightened by the black look that came upon

the jealous Queen’s face, he dived to the bottom of the well.

It was no wonder that he did so, for the Queen’s expression was not

pleasant to look at, as she darted an angry glance at her fair young

step-daughter, who was busy picking flowers some little distance

away.

Indeed, she was so annoyed at the thought that anyone should say

that the girl was prettier than she was, that she quite lost her

self-control; and. when she reached home she went up, in a violent

passion, to her room, and threw herself on the bed, declaring that

she felt very ill indeed.

It was in vain that Princess Gold-Tree asked her what the matter

was, and if she could do anything for her. She would not let the

poor girl touch her, but pushed her away as if she had been some

evil thing. So at last the Princess had to leave her alone, and go

out of the apartment, feeling very sad indeed.

By and by the King came home from his hunting, and he at once asked

for the Queen. He was told that she had been seized with sudden

illness, and that she was lying on her bed in her own room, and that

no one, not even the Court Physician, who had been hastily summoned,

could make out what was wrong with her.

In great anxiety—for he really loved her—the King went up to her

bedside, and asked the Queen how she felt, and if there was anything

that he could do to relieve her.

“Yes, there is one thing that thou couldst do,” she answered

harshly, “but I know full well that, even although it is the only

thing that will cure me, thou wilt not do it.”

“Nay,” said the King, “I deserve better words at thy mouth than

these; for thou knowest that I would give thee aught thou carest to

ask, even if it be the half of my Kingdom.”

“Then give me thy daughter's heart to eat,” cried the Queen, “for

unless I can obtain that, I will die, and that speedily.”

She spoke so wildly, and looked at him in such a strange fashion,

that the poor King really thought that her brain was turned, and he

was at his wits’ end what to do. He left the room, and paced up and

down the corridor in great distress, until at last he remembered

that that very moaning the son of a great King had arrived from a

country far over the sea, asking for his daughter’s hand in

marriage.

“Here is a way out of the difficulty,” he said to himself. “This

marriage pleaseth me well, and I will have it celebrated at once.

Then, when my daughter is safe out of the country, I will send a lad

up the hillside, and he shall kill a he-goat, and I will have its

heart prepared and dressed, and send it up to my wife. Perhaps the

sight of it will cure her of this madness.”

So he had the strange Prince summoned before him, and told him how

the Queen had taken a sudden illness that had wrought on her brain,

and had caused her to take a dislike to the Princess, and how it

seemed as if it would be a good thing if, with the maiden’s consent,

the marriage could take place at once, so that the Queen might be

left alone to recover from her strange malady.

Now the Prince was delighted to gain his bride so easily, and the

Princess was glad to escape from her step-mother's hatred, so the

marriage took place at once, and the newly wedded pair set off

across the sea for the Prince's country.

Then the King sent a lad up the hillside to kill a he-goat; and when

it was killed he gave orders that its heart should be dressed and

cooked, and sent to the Queen's apartment on a silver dish. And the

wicked woman tasted it, believing it to be the heart of her

step-daughter; and when she had done so, she rose from her bed and

went about the Castle looking as well and hearty as ever.

I am glad to be able to tell you that the marriage of Princess

Gold-Tree, which had come about in such a hurry, turned out to be a

great success; for the Prince whom she had wedded was rich, and

great, and powerful, and he loved her dearly, and she was as happy

as the day was long.

So things went peacefully on for a year. Queen Silver-Tree was

satisfied and contented, because she thought that her step-daughter

was dead; while all the time the Princess was happy and prosperous

in her new home.

But at the end of the year it chanced that the Queen went once more

to the well in the little glen, in order to see her face reflected

in the water.

And it chanced also that the same little trout was swimming

backwards and forwards, just as he had done the year before. And the

foolish Queen determined to have a better answer to her question

this time than she had last.

“Troutie, troutie," she whispered, leaning over the edge of the

well, “am not I the most beautiful woman in the world?"

“By my troth, thou art not," answered the trout, in his very

straightforward way.

“Who is the most beautiful woman, then?" asked the Queen, her face

growing pale at the thought that she had yet another rival.

“Why, your Majesty’s step-daughter, the Princess Gold-Tree, to be

sure," answered the trout.

The Queen threw back her head with a sigh of relief. “Well, at any

rate, people cannot admire her now," she said, “for it is a year

since she died. I ate her heart for my supper."

“Art thou sure of that, your Majesty?" asked the trout, with a

twinkle in his eye. “Methinks it is but a year since she married the

gallant young Prince who came from abroad to seek her hand, and

returned with him to his own country."

When the Queen heard these words she turned quite cold with rage,

for she knew that her husband had deceived her; and she rose from

her knees and went straight home to the Palace, and, hiding her

anger as best she could, she asked him if he would give orders to

have the Long Ship made ready, as she wished to go and visit her

dear step-daughter, for it was such a very long time since she had

seen her.

The King was somewhat surprised at her request, but he was only too

glad to think that she had got over her hatred towards his daughter,

and he gave orders that the Long Ship should be made ready at once.

Soon it was speeding over the water, its prow turned in the

direction of the land where the Princess lived, steered by the Queen

herself ; for she knew the course that the boat ought to take, and

she was in such haste to be at her journey’s end that she would

allow no one else to take the helm.

Now it chanced that Princess Gold-Tree was alone that day, for her

husband had gone a-hunting. And as she looked out of one of the

Castle windows she saw a boat coming sailing over the sea towards

the landing place. She recognised it as her father’s Long Ship, and

she guessed only too well whom it carried on board.

She was almost beside herself with terror at the thought, for she

knew that it was for no good purpose that Queen Silver-Tree had

taken the trouble to set out to visit her, and she felt that she

would have given almost anything she possessed if her husband had

but been at home. In her distress she hurried into the servants’

hall.

“Oh, what shall I do, what shall I do?” she cried, “for I see my

father’s Long Ship coming over the sea, and I know that my

step-mother is on board. And if she hath a chance she will kill me,

for she hateth me more than anything else upon earth.”

Now the servants worshipped the ground that their young Mistress

trod on, for she was always kind and considerate to them, and when

they saw how frightened she was, and heard her piteous words, they

crowded round her, as if to shield her from any harm that threatened

her.

“Do not be afraid, your Highness,” they cried; “we will defend thee

with our very lives if need be. But in case thy Lady Step-Mother

should have the power to throw any evil spell over thee, we will

lock thee in the great Mullioned Chamber, then she cannot get nigh

thee at all.”

Now the Mullioned Chamber was a strong-room, which was in a part of

the castle all by itself, and its door was so thick that no one

could possibly break through it; and the Princess knew that if she

were once inside the room, with its stout oaken door between her and

her step-mother, she would be perfectly safe from any mischief that

that wicked woman could devise.

So she consented to her faithful servants’ suggestion, and allowed

them to lock her in the Mullioned Chamber.

So it came to pass that when Queen Silver-Tree arrived at the great

door of the Castle, and commanded the lackey who opened it to take

her to his Royal Mistress, he told her, with a low bow, that that

was impossible, because the Princess was locked in the strong-room

of the Castle, and could not get out, because no one knew where the

key was.

(Which was quite true, for the old butler had tied it round the neck

of the Prince’s favourite sheep-dog, and had sent him away to the

hills to seek his master.)

“Take me to the door of the apartment,” commanded the Queen. “At

least I can speak to my dear daughter through it.” And the lackey,

who did not see what harm could possibly come from this, did as he

was bid.

“If the key is really

lost, and thou canst not come out to welcome me, dear Gold-Tree,”

said the deceitful Queen, "at least put thy little finger through

the keyhole that I may kiss it.”

The Princess did so, never dreaming that evil could come to her

through such a simple action. But it did. For instead of kissing the

tiny finger, her step-mother stabbed it with a poisoned needle, and,

so deadly was the poison, that, before she could utter a single cry,

the poor Princess fell, as one dead, on the floor.

When she heard the fall, a smile of satisfaction crept over Queen

Silver-Tree’s face. “Now I can say that I am the handsomest woman in

the world,” she whispered; and she went back to the lackey who stood

waiting at the end of the passage, and told him that she had said

all that she had to say to her daughter, and that now she must

return home.

So the man attended her to the boat with all due ceremony, and she

set sail for her own country; and no one in the Castle knew that any

harm had befallen their dear Mistress until the Prince came home

from his hunting with the key of the Mullioned Chamber, which he had

taken from his sheep-dog’s neck, in his hand.

He laughed when he heard the story of Queen Silver-Tree’s visit, and

told the servants that they had done well; then he ran upstairs to

open the door and release his wife.

But what was his horror and dismay, when he did so, to find her

lying dead at his feet on the floor.

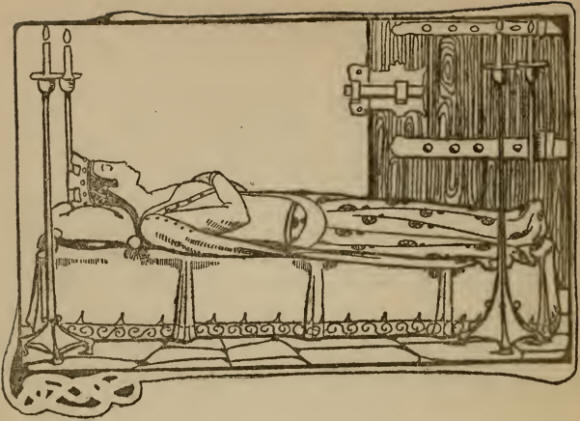

He was nearly beside himself with rage and grief; and, because he

knew that a deadly poison such as Queen Silver-Tree had used would

preserve the Princess’s body so that it had no need of burial, he

had it laid on a silken couch and left in the Mullioned Chamber, so

that he could go and look at it whenever he pleased.

He was so terribly lonely, however, that in a little time he married

again, and his second wife was just as sweet and as good as the

first one had been. This new wife was very happy, there was only one

little thing that caused her any trouble at all, and she was too

sensible to let it make her miserable.

That one thing was that there was one room in the Castle—a room

which stood at the end of a passage by itself—which she could never

enter, as her husband always carried the key. And as, when she asked

him the reason of this, he always made an excuse of some kind, she

made up her mind that she would not seem as if she did not trust

him, so she asked no more questions about the matter.

But one day the Prince chanced to leave the door unlocked, and as he

had never told her not to do so, she went in, and there she saw

Princess Gold-Tree lying on the silken couch, looking as if she were

asleep.

“Is she dead, or is she only sleeping?" she said to herself, and she

went up to the couch and looked closely at the Princess. And there,

sticking in her little finger, she discovered a curiously shaped

needle.

“There hath been evil work here,” she thought to herself. “If that

needle be not poisoned, then I know naught of medicine." And, being

skilled in leechcraft, she drew it carefully out.

In a moment Princess Gold-Tree opened her eyes and sat up, and

presently she had recovered sufficiently to tell the Other Princess

the whole story.

Now, if her step-mother had been jealous, the Other Princess was not

jealous at all; for, when she heard all that had happened, she

clapped her little hands, crying, “Oh, how glad the Prince will be;

for although he hath married again, I know that he loves thee best.”

That night the- Prince came home from hunting looking very tired and

sad, for what his second wife had said was quite true. Although he

loved her very much, he was always mourning in his heart for his

first dear love, Princess Gold-Tree.

“How sad thou art!" exclaimed his wife, going out to meet him. “Is

there nothing that I can do to bring a smile to thy face?"

“Nothing" answered the Prince wearily, laying down his bow, for he

was too heart-sore even to pretend to be gay.

“Except to give thee back Gold-Tree," said his wife mischievously.

“And that can I do. Thou wilt find her alive and well in the

Mullioned Chamber."

Without a word the Prince ran upstairs, and, sure enough, there was

his dear Gold-Tree, sitting on the couch ready to welcome him.

He was so overjoyed to see her that he threw his arms round her neck

and kissed her over and over again, quite forgetting his poor second

wife, who had followed him upstairs, and who now stood watching the

meeting that she had brought about.

She did not seem to be sorry for herself, however. “1 always knew

that thy heart yearned after Princess Gold-Tree," she said. “And it

is but right that it should be so. For she was thy first love, and,

since she hath come to life again, I will go back to mine own

people."

“No, indeed thou wilt not," answered the Prince, “for it is thou who

hast brought me this joy. Thou wilt stay with us, and we shall all

three live happily together. And Gold-Tree and thee will become

great friends."

And so it came to pass. For Princess Gold-Tree and the Other

Princess soon became like sisters, and loved each other as if they

had been brought up together all their lives.

In this manner another year passed away, and one evening, in the

old* country, Queen Silver-Tree went, as she had done before, to

look at her face in the water of the little well in the glen.

And, as had happened twice before, the trout was there. “Troutie,

troutie," she whispered, “am not I the most beautiful woman in the

world?"

“By my troth, thou art not," answered the trout, as he had answered

on the two previous occasions.

“And who dost thou say is the most beautiful woman now?” asked the

Queen, her voice trembling with rage and vexation.

“I have given her name to thee these two years back,” answered the

trout. “The Princess Gold-Tree, of course.”

“But she is dead,” laughed the Queen. “I am sure of it this time,

for it is just a year since I stabbed her little finger with a

poisoned needle, and I heard her fall down dead on the floor.”

“I would not be so sure of that,” answered the trout, and without

saying another word he dived straight down to the bottom of the

well.

After hearing his mysterious words the Queen could not rest, and at

last she asked her husband to have the Long Ship prepared once more,

so that she could go and see her step-daughter.

The King gave the order gladly; and it all happened as it had

happened before.

She steered the Ship over the sea with her own hands, and when it

was approaching the land it was seen and recognised by Princess

Gold-Tree.

The Prince was out hunting, and the Princess ran, in great terror,

to her friend, the Other Princess, who was upstairs in her chamber.

“Oh, what shall I do, what shall I do?” she cried, “for I see my

father’s Long Ship coming, and I know that my cruel step-mother is

on board, and she will try to kill me, as she tried to kill me

before. Oh ! come, let us escape to the hills.”

“Not at all,” replied the Other Princess, throwing her arms round

the trembling Gold-Tree. “I am not afraid of thy Lady Step-Mother.

Come with me, and we will go down to the sea shore to -greet her.”

So they both went down to the edge of the water, and when Queen

Silver-Tree saw her step-daughter coming she pretended to be very

glad, and sprang out of the boat and ran to meet her, and held out a

silver goblet full of wine for her to drink.

“’Tis rare wine from the East,” she said, “and therefore very

precious. I brought a flagon with me, so that we might pledge each

other in a loving cup.”

Princess Gold-Tree, who was ever gentle and courteous, would have

stretched out her hand for the cup, had not the Other Princess

stepped between her and her stepmother.

“Nay, Madam,” she said gravely, looking the Queen straight in the

face; “it is the custom in this land for the one who offers a loving

cup to drink from it first herself.”

“I will follow the custom gladly,” answered the Queen, and she

raised the goblet to her mouth. But the Other Princess, who was

watching for closely, noticed that she did not allow the wine that

it contained to touch her lips. So she stepped forward and, as if by

accident, struck the bottom of the goblet with her shoulder. Part of

its contents flew into the Queen’s face, and part, before she could

shut her mouth, went down her throat.

So, because of her wickedness, she was, as the Good Book says,

caught in her own net. For she had made the wine so poisonous that,

almost before she had swallowed it, she fell dead at the two

Princesses’ feet.

No one was sorry for her, for she really deserved her fate; and they

buried her hastily in a lonely piece of ground, and very soon

everybody had forgotten all about her.

As for Princess Gold-Tree, she lived happily and peacefully with her

husband and her friend for the remainder of her life.

|