|

During the period comprised in the previous

chapter Mr. Fairbairn was engaged, for four years, on a work of such

importance and novelty as to merit special description. This was the great

series of experimental investigations necessary to determine the details and

proportions of the colossal wrought-iron tubular bridges erected on the

Chester and Holyhead Railway.

After the close of his connection with this

work, in 1849, Mr. Fairbairn published a book, the title of which is as

follows :—

'An Account of the Construction of the Britannia

arid Conway Tubular Bridges; with a complete history of their progress, from

the conception of the original idea to the conclusion of the elaborate

experiments which determined the exact form and mode of construction

ultimately adopted.' By William Fairbairn, C.E., Memb. Inst. Civil

Engineers, Vice-President of the Literary and Philosophical Society,

Manchester, &c. London: Weale; Longman & Co. 1849.

As this work expressed Mr. Fairbairn's matured

views on this subject, it will naturally form the most appropriate basis for

the brief notice to be given in this chapter, Reference may be made to the

work itself for further details.

The following extracts give an account of the

origin and early history of the proceedings :—

In the construction of the Chester and Holyhead

Railway two formidable obstacles had to be overcome. The deep and rapid

tidal streams at the Conway and Menai Straits had to he crossed by bridges

which must necessarily be of extraordinary span, and of great strength. No

centerings or other substructures, such as are usually resorted to for

putting such massive structures together, could be erected.

Under such circumstances the most obvious

resource of the engineer was a suspension bridge, but the failure of more

than one attempt had proved the impossibility of running railway trains over

bridges of that class with safety. Some new expedient of engineering was

therefore required, and an engineer bold and skilful enough to conceive such

an expedient and to apply it. That engineer was found in Mr. Robert

Stephenson, and that expedient is the one, the history of which it is the

object of the following pages to relate.

Having to encounter extraordinary difficulties

of execution, and being compelled by the Admiralty [who opposed the erection

of any structure which should offer a hindrance to the free passage of

vessels under it] to abandon the ordinary resources of the engineer, Mr.

Stephenson conceived the original idea of a huge tubular bridge, to be

constructed of riveted plates and supported by chains, and of such

dimensions as to allow of the passage of locomotive engines and railway

trains through the interior of it.

It was with reference to this expedient, after

all others had been found inapplicable, that I was consulted by him, and

that my opinion was requested, first as to the practicability of the scheme,

and secondly as to the means necessary for carrying it out. This

consultation took place early in April 1845, and, as far as could be

gathered from Mr. Stephenson at the time, his idea then was that the tube

should be either of a circular or an egg-shaped sectional form.

At th^S .period there were no drawings

illustrative of the original idea of the bridge, nor had any calculations

been made as to the strength, form, or proportions of the tube. It was

ultimately arranged that the subject should be investigated experimentally,

to determine, not only the value of Mr. Stephenson's original conception,

but that of any other tubular form of bridge which might present itself in

the prosecution of my researches. The matter was placed unreservedly in my

hands; the entire conduct of the investigation was entrusted to me; and, as

an experimenter, I was to be left free to exercise my own discretion in the

investigation of whatever forms or conditions of the structure might appear

to me best calculated to secure a safe passage across the Straits. This

freedom of action was obviously necessary to the success of my experiments.

I cannot but feel myself to have been honoured by that confidence in my

judgment which it implied.

The whole series of experiments (detailed in the

Appendix) was conducted at my works, Jlillwall, Poplar.

By July 21 a considerable number of experiments

had been made; nearly the whole of the cylindrical tubes had been tested,

and preparations were then in progress for the rectangular and elliptical

forms. The difficulties experienced in retaining the cylindrical tubes in

shape, when submitted severe strains, naturally suggested the rectangular

form. Many new models of this kind were prepared and experimented on before

the end of July, and others, with different thicknesses of the top and

bottom plates, or flanches, before August 6.

On this (lay he wrote a letter to Mr.

Stephenson, which clearly pointed to the principle thenceforward adopted in

regard to the benni—namely, that of treating it as a hollow girder. The

letter says:—

From these investigations we derive several

important facts, one of which I may mention, namely, the difficulty of

bringing the upper, as well as the lower, side of the bridge into the

tensile strain. For this object several changes were effected, and attempts

made to distribute the forces equally, or in certain proportions throughout

the parts, but without effect, the results being in every experiment that of

a hollow beam, or girder, resisting, in the usual way, by the compression of

the upper and extension of the lower sides. In almost every instance we have

found the resistance opposed to compression the weakest; the upper side

generally giving way from the severity of the strain in that direction.

These facts are important so far as they have

given rise to a new series of experiments calculated to stiffen or render

more rigid the upper part of the tube, as well as to equalise the strain,

which in our present construction is evidently too weak for the resisting

forces of compression.

Mr. Fairbairn continues his narrative :—

It w ill be seen by this letter that the

weakness of the tube had been recognised in its upper surface, which yielded

to compression before the under side was upon the point of yielding to

extension; and that the course which the experiments henceforth took, of so

strengthening the upper surface that it should not be on the point if

yielding to compression until the under surface was about to yield by

extension, had been already shaped out ... I had ordered the top of the

tube to be thickened. It now occurred to me that the top might be

strengthened more effectually by other means than by thickening it, and I

directed two additional tubes to be constructed, the one rectangular and the

other elliptical, with hollow triangular cells or fins to prevent crushing.

These experiments led to the trial of the

rectangular form of tube with a corrugated top, the superior strength of

which decided me to adopt that cellular structure of the top of the tube

which ultimately merged in a single row of rectangular cells. It is this

cellular structure which gives to the bridges now standing across the Conway

Straits their principal element of strength.

In a letter to Mr. Stephenson, dated September

20, 1845, Mr. Fairbairn, after describing the experiments with the tubes,

adds:—

It is more than probable that the bridge, in its

full siae, may take something of the following sectional shape.

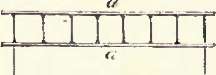

The parts a a being two longitudinal plates,

elivided by vertical plates so as to form squares, calculated to resist the

crushing strain in the first instance; and the lower parts b b, also

longitudinal plates, well connected with riveted joints, and of considerable

thickness to resist the tensile strain in the second.

Mr. Fairbairn remarks on this :—

The reader will not fail to observe how much

this sketch resembles the tubes actually constructed for the Conway and

Britannia Bridges.

Mr. Faibrairn's first sketch for the tube of the

Britannia bridge.

Towards the end of August Mr. Fairbairn

considered that the experiments had assumed a shape which seemed to require

the assistance of a mathematician, in order to deduce, from the trials on a

small scale, formula; and modes of calculation applicable to a larger size.

For this purpose he invited the assistance of Mr. Eaton Hodgkinson, who, it

will be recollected, had already been associated with Mr. Fairbairn in

investigations on the strength of iron. Mr. Stephenson concurred in the

proposition, and Mr. Hodgkinson first visited Millwall on September 19.

The square cell tube, although so clearly

indicated in the above letter, was not, however, at once tried; for Mr.

Fairbairn preferred to experiment on another modification of the same

principle—namely, a rect angular tube having a corrugated top, resembling in

section the eyes of a pair of spectacles. This was tried on October 14, and

Mr. Fairbairn, writing the next day to Mr. Stephenson, says:—

Our experiments of yesterday were the best and

most satisfactory we have yet made; and, agreeable to expectation, the form,

as per annexed sketch, gave not only the greatest strength, but what was of

equal importance, there was a near approximation to an equality of the

forces on the top and bottom sides. .... It is evident we are approaching

the strongest form. . . I think we have sufficient data to guide you as to

the security of such a structure.

Mr. Fairbairn adds:—

It is from this period that I date the

disappearance of almost every difficulty respecting the construction and

ultimate formation of the Britannia and Conway tubes. The powerful

resistance offered to compression by the cellular form of the top, as

exhibited in the last experiment, at once decided in my mind the form to be

adopted in those for the large tubes; and from that time forward I had no

doubts as to the practicability and complete success of the undertaking.

Towards the end of the year it became necessary

for Mr. Stephenson to make some report to the directors of the Chester and

Holyhead Railway. They had up to this time shown a great deal of patience,

and had watched with much interest the progress of the experiments at

Millwall; but as the next general meeting of the shareholders was

approaching, the directors naturally desired to have some definite

statements to produce.

It was accordingly arranged that Mr.

Stephenson's own report to the directors should be accompanied by two

separate ones, by Mr. Fairbairn and Mr. Hodgkinson respectively, each giving

his own views relative to the experiments, as well as to the chance3 of

ultimate success in the construction of the bridges.

Mr. Stephenson's Report was dated February 9,

1846, and the three documents are given entire iu Mr. Fairbairn's book. A

few extracts will serve to illustrate Mr. Fairbairn's position in the

matter. Mr. Stephenson says:—

I will lay before you the results of the

experimental investigation, which, with your sanction, I commenced some

months ago in reference to the construction of the bridge over the Menai

Straits.

In conducting this experimental investigation I

saw the importance of avoiding the influence of any preconceived views of my

own, or at least to check them, by calling in the aid of other parties

thoroughly conversant with such researches. For this purpose I have availed

myself of the assistance of Mr. Fairbairn and Mr. Hodgkinson; the former so

well known for his thorough practical knowledge in such matters; and the

latter distinguished as the first scientific authority on the strength of

iron beams.

lie then gives a resume of the experiments made

to that time, which had, he said, served to determine finally two essential

points—namely, the form of the tube, which should be rectangular, and the

distribution of the material, which should be such as to throw the greatest

thickness into the upper side. The important question remaining to be

determined was the absolute ultimate strength of a tube of my given

dimensions, which required further experimental elucidation.

There bad been an idea, in the first instance,

of using, for the erection of the tubes, large suspension chains on each

side, and Mr. Stephenson had contemplated retaining these permanently m

their position as an auxiliary support for the tubes. Mr. Fairbairn had

expressed the opinion that these were unnecessary, and Mr. Stephenson

remarks on the subject as follows:—

You will observe in Mr. Fairbairn's remarks that

he contemplates the feasibility of stripping the tube entirely of all the

chains that may be required in the erection of the bridge ; whereas, on the

other hand, Mr. Hodgkinson thinks the chains will lie an essential, or at

all events a useful auxiliary, to give the tube the requisite strength and

rigidity. This, however, will be determined by the proposed additional

experiments, and does not interfere with the construction of the masonry,

which is designed so as to admit of the tube, with or without the chains.

The application of chains as an auxiliary has

occupied much of my attention, and I am satisfied that the ordinary mode of

applying them to suspension bridges is wholly inadmissible in the present

instance; if therefore it be hereafter found necessary or desirable to

employ them in conjunction with the tube, another mode of applying them must

be devised, as it is absolutely essential to attach them in such manner as

to preclude the possibility of the smallest oscillation. In the

accomplishment of this I see no difficulty whatever, and the designs have

been arranged accordingly, in order to avoid any further delay.

It will be noticed that Mr. Fairbairn was the

only one of the three reporters who gave a positive and decided opinion

against the use of chains; Mr. Hodgkinson decidedly recommending them, and

Mr. Stephenson appearing, by his expressions, rather favourable to them than

otherwise. Now, as ultimately the chains were abandoned, not only for

permanent, but even for temporary use, the event testified strongly to Mr.

Fairbairn's sagacity and soundness of judgment in a matter so confessedly

novel and obscure.

Mr. Fairbairn's Report gave a succinct account

of the experiments which had been conducted—namely, 9 on cylindrical tubes,

5 on elliptical, and 10 on rectangular tubes. These tubes varied from about

17 to 30 feet long, and from 7 to 24 inches in transverse dimensions, and

the trials clearly proved the superiority of the rectangular form and the

cellular top. Mr. Fairbairn expressed great confidence as to the ultimate

success of the undertaking and the self-supporting power of the tube.

After the presentation of these reports, the

experiments were continued, with the view of determining more accurately the

dimensions and strength of the structure ; but before much more was done Mr.

Hodgkinson, in March 1846, requested that his share of the work should be

performed separately and under his own control; and as Mr. Stephenson

acceded to this, Mr. Hodgkinson had no further connection with Mr.

Fairbairn's proceedings.

In April Mr. Fairbairn communicated to Mr.

Stephenson an account of further experiments, which had enabled a rough

preliminary estimate to be made out of the dimensions of the real tube. Mr.

Fairbairn also began to give some attention to the details of construction,

proposing certain modes of connecting the plates by riveting, which he

considered would be advantageous.

It was further determined to construct a large

model tube, in every respect accurately proportioned to one-sixth of the

dimensions of the real structure; this, Mr. Fairbairn remarked to Mr.

Stephenson, would complete everything necessary for their practical

guidance.

About April 184(1, the design of the bridges was

commenced in earnest, the drawings were put in hand, and measures were

considered and discussed for obtaining the material and arranging the

manufacture. The distribution of the metal, the sizes of the plates, and the

methods to be pursued for putting them together, became matters of

considerable importance, and much time and thought were devoted to them Mr.

Fairbairn's duties now became more onerous. It was no longer the making and

testing of small models that he had to do. He was required to render

efficient aid iu the designs and manufacture of the largest and most

important iron constructions that had ever been known, thousands of tons in

weight, and involving great novelty, both in principle and detail. Hence it

became desirable that his position and occupation in regard to the work

should be acknowledged and clearly defined; and, with Mr. Stephenson's

concurrence, this was done at a board meeting of the directors of the

Chester and Holyhead Railway on May 13, 1816. The following is an extract

from the official minutes:—

Resolved:—1. That Mr. Fairbairn be appointed to

superintend the construction and erection of the Conway and Britannia

Bridges, in conjunction with Mr. Stephenson.

2. That Mr. Fairbairn have, with Mr. Stephenson,

the appointment of such persons as are necessary, subject to the powers of

their dismissal by the directors.

3. That Mr. Fairbairn furnish a list of the

persons he requires, with the salaries that he proposes for all foremen or

others above the class of workmen.

4. That advances of money be made on Mr.

Fairbairn's requisition and certificates, which, with the accounts or

vouchers, are to be furnished monthly.

The works connected with the first bridge it was

intended to erect, that at Conway, may be said then to have fairly

commenced, and we find Mr. Fairbairn hard at work iu regard to various

practical matters connected with the construction—visiting ironworks,

arranging workshops and tools, preparing for letting the contracts, and so

on. The large model tube was pushed on, and was completed, ready for

experiment, in June. It was 75 feet long, 4 feet 0 inches high, and 2 feet 8

inches wide. It was tested to destruction, by hanging weights on it till it

gave way, the object being to find out the weak places, and to ascertain how

it would fail. After each trial the injured and defective parts were cut out

and the tube was restored to its original form, with plates of altered

strength, as indicated by the nature and appearance of the fracture, and as

circumstances might require. This was done seven different times, until

proportions were arrived at which appeared to be satisfactory, as giving all

the strength of which such a tube was capable. By the middle of July a

decision had been come to as to the proportions and distribution of material

to be adopted in the real tubes.

About this time we find Mr. Fairbairn

considering and proposing plans for the erection and fixing of the bridges,

and earnestly urging on Mr. Stephenson the abandonment of the proposed

suspension chains. In August he was at the Menai Straits attending to the

arrangements there.

Mr. Stephenson was away on the Continent till

the end of September, and on his return the contract drawings and

specifications, which had been prepared by Mr. Fairbairn in conjunction with

Mr. Edwin Clark (Mr. Stephenson's chief assistant on the bridge), were

ready.

The contracts took some time to settle, but they

were not of such a nature as to shut out alterations and improvements in the

forms or proportions of the tubes, as new information was obtained. The

experiments and investigations still went on, and the forms of the cells and

other points of detail underwent careful discussion.

At the end of the year 1846 Mr. Fairbairn, after

visiting several manufactories, reported progress in the preparations for

the construction of the tubes.

When the contracts were first considered, it was

proposed that Mr. Fairbairn's firm should take an important share in the

manufacture. Mr. Stephenson, writing to Mr. Fairbairn on October 25, said:—

I am sincerely glad that your son and Ditchlmrn

[another maker] have succeeded in arranging with the Company. We must put

the whole of the Britannia into their hands, as I am sure the others are

unequal to the thing. We must visit both their establishments when I come

down to Manchester.

In reference to this, Mr. Fairbairn says

afterwards:—

A joint contract, which had been entered into by

my son, as representative of the tirm of Messrs. Fairbairn and Sons,

Millwall, with Messrs. Ditchburn and Mare, of Blackwall, for constructing

the greater part of the tubes for the Britannia Bridge, was looked upon w

ith suspicion by the board. Although interested as a partner, I had not

personally interfered in the matter, and I was even unacquainted with the

terms of agreement between the two firms; but when the feelings which were

entertained by the directors were made known to me, and as it appeared

difficult for me, in consequence of the partnership, to maintain a perfectly

independent position, I urged a transfer of the whole contract into the

hands of Messrs. Ditchburn and Mare. This transfer was afterwards

satisfactorily arranged by my son and Mr. J tare, and approved of by the

Company.

The detailed dimensions of some parts of the

tubes continued to be under consideration, as more light was thrown on the

nature of the forces and resistances, until about the spring of 1847, when

the whole may be said to have been finally arranged.

All this time Mr. Fairbaim was occupied in

various matters connected with the work, and, among others, with the mode of

erecting it. On March 24, 1817, he wrote to Mr. Stephenson :—

I have now completed, or nearly completed, the

whole of the drawings fur the framework, girders, &e., for lifting the

tubes. The arrangement of the hydraulic apparatus, chains, &e., is also

complete; and as soon as we. have copied the drawings &c„ the whole shall be

laid before you. 1 am now well satisfied as to the security of the ends of

the tubes, where the chains [for lifting them] are to be attached, as also

the large girders, and all the roller platforms, which are now secure and in

a most satisfactory position.

The actual manufacture of the tubes also engaged

his attention, although the superintendence of this was not strictly within

his province. On June 8 Mr. Stephenson wrote to him :—

I am much gratified at your resolution to devote

a considerable portion of your time to looking the tube builders up, and

getting a good job made of the whole affair.....What would be most valuable

is a regular periodical visit, so that the progress may be narrowly watched,

and advantage taken of every new continuation [contrivance] as it occurs. Of

these there will be many, which must suggest improvements in our

arrangements.

Mr. Fairbairn answered, June 9 :—

I have made up my mind to devote my best

energies to the construction and due completion of the tubes, and I will

watch narrowly and regularly the progress of each construction, that the

work be well done, and free from blemish in every respect.

As the time approached for making arrangements

for the erection, Mr. Fairbairn wrote, August 1(1, to Mr. Stephenson:—

Will you write me whether it is your wish that I

should take charge of the floating and raising of the tubes ? I have no

objection to do it, and to take the management of the whole thing, subject

to your approval, and to be responsible for the result.

Mr. Stephenson answered, August 23 :—

I was surprised at your letter this morning,

asking if I wished you to take charge of the floating and lifting. I

consider you as acting with me in every department of the proceedings, and I

shall regret if anything has been done which has conveyed to you the idea

that I was not desirous of having the full benefit of your assistance in

every particular.

On January 7, 1818, Mr. Stephenson wrote .—

I am glad to hear from your note, received this

morning, that all is progressing satisfactorily, though not with that

despatch which could be desired. Your presence will do much, and I hope you

will give as large a portion of your time as you can possibly spare.

It hail been decided that, in order to ascertain

the strength of the structure by actual trial, the first tube completed,

that at Conway, should, before putting it in its place, be tested by

supporting it on its ends and loading it with a considerable weight. This

test was made at the end of January, and on February 2 Mr. Fairbairn wrote

to the effect that the anticipations derived from the experiments on the

model had been fully borne out by the trials of the real tube. A few weeks

later the tube was hoisted into its place, and the trains passed through it

in April 1848, Mr. Fairbairn continuing to give his aid in the matter until

the solution of the great problem was practically completed.

Shortly after this time, some misunderstandings

having unfortunately arisen as to the precise nominal position Mr. Fairbairn

occupied (there could be none as to the value of the services he had

rendered) in regard lo the bridges, he did not feel it consistent with his

self-respect that he should continue his connection with them, and on May

22, 1848, he wrote to the directors resigning the appointment he had

formally received from them two years before.

He then put in hand the book mentioned at the

beginning of the present chapter, with the object of giving an authentic

record of the proceedings he had been a party to, in reference to these

bridges, and thereby establishing his claims to what he considered an

important share in the merit of their construction. In the preparation of

this work (the largest literary effort that had yet proceeded from his pen)

he had the assistance of many friends, among others the late Eev. IT.

Moseley, Canon of Bristol, and Mr. Tate, of Battersea, the latter gentleman

furnishing the many mathematical calculations which the book contained.

Many other men eminent in science also actively

interested themselves in Mr. Fairbairn's work on these bridges, among whom

may be mentioned Sir David Brewster, Mr. George Rennie, Mr. James Nasmyth,

Dr. Andrew Tire, Mr. C. Babbage, and Professor James D. Forbes.

Mr. Babbage wrote thus in answer to an

invitation from Mr. Fairbairn:—

My dear Sir,—I very much regret the

impossibility of my accepting your very agreeable invitation for next week.

I have been compelled to leave London on account of my health, and am

endeavouring, by the aid of sea air and quietness, to recruit it. This will

detain me in the West of England as long as circumstances permit. It is now

several years since I have visited your part of England, and I know how

rapidly it advances. I am, therefore, very anxious to take the earliest

opportunity of renewing my acquaintance with it, and of studying those great

mechanical advances in which you have taken so large a part.

I am, my dear Sir, yours faithfully,

C. Bibbage.

Ashley Combe, Purtlick, Somersetshire, September

3, 1818.

Another letter, from one of the cleverest

practical mechanics of the age, contains also some interesting passages:—

Patricoft, December 15, 1819.

My dear Sir,—Feeling such a lively interest as I

shall always do in all that relates to your well-earned fame, and having,

from the first, through your great kindness, noted the development of this

masterpiece of your genius, I did not fail to purchase a copy of your work

when it first came out, and have perused it again and again with the deepest

interest. I assure you I feel most proud in being thought worthy of

receiving a copy of your work direct from the author, and shall store it up

along with a few other much valued treasures, and so let my locomotive copy

free to run ahout telling the truth in many a quarter where the truth ought

to be known, and where it can be justly appreciated.

Tile Earl of Ellesmere has taken a most lively

interest in this affair, and, after carefully perusing your work, I think it

would have done your heart good to have heard the way in which he gave forth

his verdict, one afternoon, before some rather influential folks. Long may

you live to enjoy the fame (and,I trust, the profit) which shall attend your

triumphant introduction of a new era in engineering, which is destined to do

mankind most mighty service!

With kindest regards to Mrs. Fairbairn, in which

Mrs. Kasmyth desires to unite,

Believe me, I am yours most faithfully,

James Nasmyth.

During the course of Mr. Fairbairn's experiments

it seems to have occurred to him that the principle which was being

developed might be made of extended application for bridges generally,

particularly on railways; and as its application involved points of novelty,

he, with Mr. Stephenson's concurrence, took out a {latent for the

improvement. It is dated October 8, 1816, and bears the official number

11,401. The title is for 'Improvements in the construction of iron beams for

the erection of bridges and other structures.' It states the nature of the

improvement to consist—

In the novel application and use of plates of

metal, united by means of rivets and angle iron, for such or similar

purposes, and forming by such combination a hollow iron beam or girder.

The drawings show several varieties of

wrought-iron girders, all embodying the hollow or ' box' construction with a

cellular top, combining peculiar stiffness and lightness with great facility

of construction.

Mr. Fairbairn states in regard to this patent:—

The patent for wrought-iron girder bridges was a

joint affair between Mr. B. Stephenson and myself. It was in my name as the

inventor, but he paid half the expense, and was entitled to one half the

profits, but it ultimately became a dead letter, and was abandoned by Mr.

Stephenson.

Under the circumstances the question was, shall

I continue to build the bridges. I chose to do so, and I believe I did

right, as the principle was quite new, and no one understood the

construction so well. I therefore gave designs, and received orders for more

than one hundred bridges in the course of a very few years. Up to the

present time, 1870, I have built and designed, with the assistance of the

Fairbairn Engineering Company, nearly one thousand bridges, some of them of

large spans varying from 40 to 300 feet. |