|

The autobiography, which has formed the

substance of the nine preceding chapters, extends no further, in any

connected shape, than about 1810, when Mr. Fairbairn had completed his

fiftieth year. Some notes remain, referring to matters of a later date; but

they are fragmentary and incomplete, and can only be made use of as

subsidiary explanations.

But although, in regard to that portion of his

life and work which remains to be chronicled, we lose the benefit of his own

interesting and vivid narration, we are fortunately not left altogether

without guidance. Mr. Fairbairn was very fond of writing; nothing gave him

greater pleasure than to put his ideas on paper; and hence, in regard to the

later occupations of his life, there exists a mass of information from his

hand, either published or in manuscript, which has served not only to

facilitate the task of the biographer, but to render the accounts given

authoritative and trustworthy.

In the present chapter it is proposed, in the

first place, to give a brief notice of several miscellaneous matters,

scientific and professional, which occupied Mr. Fairbairn's attention

between his fiftieth and sixtieth years; and, secondly, to chronicle some

few private and domestic events of interest that happened during the same

period.

In 1840 Mr. Fairbairn was consulted regarding

the best means to be adopted for draining the lake of Haarlem; and he

appears to have devised an ingenious mechanical arrangement to facilitate

the process; but no record of any report on the subject can be found.

In the same year he became one of the managing

council of a society formed in Manchester under the presidency of the Right

Hon. Lord Francis Egerton, called the Manchester Geological Society, and

although not properly speaking a geologist, he contributed a paper to their

meetings which was read on October 29, 1840, and was published the following

year in vol. i. of their Transactions.

The paper was entitled 'On the Economy of

raising Water from Coal Mines on the Cornish Principle.' It gave an account

of the improvements made in the steam-engines for draining the mines of

Cornwall, and the great economy of fuel resulting therefrom; and it

advocated the introduction of similar improvements in the colliery

districts. It was illustrated by drawings of the engine, and by copies of

diagrams of the steam-pressure indicator.

Mr. Fairbairn continued to prosecute his

experiments on the strength of cast-iron ; and in November, 1840, he read,

before the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester, a second paper,

entitled

'An experimental Enquiry into the Strength and

other Properties of Anthracite Cast-iron, being a continuation of a series

of experiments on British irons from various parts of the United Kingdom.'

This paper was published tn the same volume as

the former one. and it gave an account of the extension of the trials to a

new kind of iron that had been introduced into the market, named anthracite

iron from its being prepared with anthracite coal.

The following letter from Sir. Fairbairn's

fellow-worker in these important iron experiments will be interesting as

showing the zealous and earnest part Mr. Fairbairn took in the

investigations. The parts omitted refer to private matters.

Manchester, December 11, 1810.

My dear Sir,—Very many thanks for your kind

letter of this morning. . . . The sentiments your liberality has inspired

are deeply engraven upon my heart.

It is perhaps not less than a dozen years since

I first availed myself of your (and your then partner's) kind offer to

afford me the means of making experiments at your works. In that interval

more experiments, of a really useful character, have been made there, either

by yourself or me, than have been made at any one place in Europe in the

time ; and when one considers that the expense has been wholly borne by

yourself . . . your public spirit deserves the highest praise. This praise

has been expressed to me a hundred times, and every man of science seems

willing to join in it.

I had not expected that we should have parted so

soon. We have both run for some years an interesting race for reputation in

practical science, mutually indebted to each other; and though your name is

now not bounded by Europe, it might have been (perhaps) no worse for either

of us if it had been our lot jointly to investigate the steam-engine.

I should have gone to-day, but as the extra

copies of thd paper on Pillars arrived at the same time with your letters of

introduction, I thought they might be an auxiliary if taken with me, and I

would stay till Monday and dispose of some of them. I have sent five for

your use besides those which are addressed, and if you would like more I

will send you any number.

Remember me with every sentiment of respect to

Mrs. Fairbairn and your amiable daughter. Thank them for the kindness they

have long shown to me, and believe me,

Ever yours,

Wm. Fairbairn, Esq. Eaton Hodgkinson.

Another letter, written by the same gentleman a

little later, is in the same strain:—

March 10, 1842.

My dear Sir,—I have received the medals safe,

which through your liberality in the encouragement of enquiries into

practical science, I have had the honour to obtain. It will afford me very

great pleasure to visit your hospitable lady and yourself on Monday at six.

Mrs. II. is, thank God, somewhat better to-day, and if ever I saw a gleam of

pleasure marked strongly upon her countenance, it was when she saw the

medals which you have enabled me to obtain.

With every feeling of affection and gratitude,

believe me, my dear Sir (both on her part and my own) most truly yours,

Wm. Fairbairn, Esq. Eaton Hodgkinson.

In 1841 Mr. Fairbairn was applied to, at the

suggestion of the government, to give advice as to the best means of

preventing accidents to workpeople in factories by their getting entangled

in the machinery. It was considered advisable that mill-owners should be

compelled to box or fence off all dangerous moving parts; but that the

opinion of skilled persons should be taken as to how far this could be done

without interfering with the convenience of working. Mr. Fairbairn gave the.

required information at some length in a report to Mr. Heathcote, the local

factory inspector, dated April 8,1841, and he encouraged the enforcement of

the protection, if kept within reasonable bounds.

In 1842 he took out a patent (July 7, No. 9,409)

for ' certain improvements in the construction of metal ships, boats, and

other vessels, and in the preparation of metal plates to be used therein.'

The object of this invention was to avoid the

weakening of wrought-iron plates due to the ordinary process of riveting. To

prepare for this process it is necessary to punch holes in the edges of the

plates to be riveted] by which of course the metal is considerably cut away,

and much loss of strength ensues. To remedy this, Mr. Fairbairn proposed to

roll the plates somewhat thicker on the edges, so that the holes being made

in the thickened parts, the extra strength would compensate for the area

removed by the holes.

This invention was partially carried into

practice. An iron steamboat of some magnitude was built for the Admiralty on

the system, and it was also used to some extent for locomotive boilers. But

it has been found that the extra trouble and expense of getting plates

specially rolled with the thickened edges are objected to, and hence the

plan has not come into general application.

In 1842 aud the following year Mr. Fairbairn

undertook some elaborate investigations on a subject that had often excited

the attention of practical engineers, but on which very crude and indistinct

notions appear to have generally prevailed, namely, the prevention of

smoke from steam-engine boilers. At the meeting of the British Association

at York, in September 1844, he presented a report ' On the Consumption of

Fuel and the Prevention of Smoke,' which was published in the volume of

Transactions for that year.

It begins by stating—

There is perhaps no subject so difficult, and

none so full of perplexities, as that of the management of a furnace and the

prevention of smoke. I have approached this enquiry with considerable

diffidence, and, after repeated attempts at definite conclusions, have more

than once been forced to abandon the investigation as inconclusive and

unsatisfactory.

After alluding to the nature of the

difficulties, the author adds:—

I shall endeavour to show, from a series of

accurately-conducted experiments, that, the prevention of smoke, and the

perfect combustion of fuel, are synonymous, and completely within the reach

of all those who choose to adopt measures calculated for the suppression of

the one and the improvement of the other.

He divides his essay under four heads of enquir

:—

The analysis or constituents of coal and other

fuels.

The relative proportions of the furnace and forms of boilers.

The temperature of the furnace and surrounding flues.

The economy of fuel, concentration of heat, and prevention of smoke.

All which are fully treated in the paper.

In the same year (1844) Mr. Fairbairn was called

on, in the course of his professional business, to investigate a subject

which occupied him for a long time afterwards, namely, the use of iron in

the construction of large buildings.

The first occasion for this study was an

application from Liverpool, where, for some years, an enormous loss of

property had been sustained by fires in large warehouses. From 1795 to the

end of 1842 this loss had amounted to two millions and a quarter sterling ;

and the damage by one lire alone, in September 1841, was estimated at

380,000W. In fact, Liverpool had acquired an unenviable notoriety for the

frequency and extent of the fires ; the character of the town had become

stamped as insecure for the storage of merchandise, and the rates of

insurance had been raised to such a pitch as to prove a most serious charge

and embarrassment to the commerce of the port.

This led to an urgent demand for ameliorations

in the construction of the warehouses, particularly by the free use of iron

in place of timber. Hut as such an application of this material was to a

certain extent novel, it was felt to be desirable that the opinion and

advice of a thoroughly competent engineer should be obtained ; and at the

end of March 1844 Messrs. S. and J. Holme, large builders and contractors of

Liverpool, applied to Mr. Fairbairn to visit that town, and make a report on

the matter, as they were about to erect a new warehouse of great magnitude,

covering nearly an acre of ground. 'The subject,' said Messrs. Holme, 'is

most important to the commerce of the town, as well as to many persons

individually, and as we shall not like to take any steps in regard to the

large pile, we shall esteem it a favour if you will name the earliest day in

your power to visit Liverpool.'

Mr. Fairbairn paid the visit asked for, and made

his report on June 3. He pointed out that fire-proof modes of construction

had for some time been introduced for mills and factories, described their

peculiarities, particularly in regard to the strength of the iron columns,

girders, &c., and recommended the application of the same principles to the

case of warehouses, concluding with the following remark:—

In my own mind there is not the shadow of a

doubt as to the security of such a structure, and I do not hesitate to

assert that a well-built and properly-arranged fire-proof warehouse can not

only be constructed, but may be made to entail upon the commercial and

manufacturing communities of this country an important and lasting benefit.

This report was thought so valuable to the

Liverpool interests, that it was published, with introductory remarks by

Messrs. Holme, for general circulation, and was reprinted in the 'Edinburgh

New Philosophical Journal,' vol. xxxviii., 1845.

A few months later Mr. Fairbairn's attention was

again directed to the construction of large buildings by a dreadful accident

that occurred at Oldham. On October 31 a large cotton-mill in that town fell

in with a tremendous crash, burying a number of work-people beneath the

ruins, and destroying property to a very large amount. At the coroner's

inquest the jury expressed a wish that the circumstances should be enquired

into by Mr. Fairbairn, in association with a Mr. D. Bellhouse. This was

done, and a joint Eeport, dated November 0, was presented at the adjourned

inquest by the two gentlemen, who also gave viva voce explanations. They

ascribed the accident to the weakness of some of the iron beams, which it

appeared had been constructed without due regard to the mechanical

principles determining their strength. The jury, in returning a verdict of

accidental death, added ' their unanimous opinion that the causes of the

accident were fully pointed out in the able report of Mr. Fairbairn and Mr.

Bellhouse.'

At this time a Commission or Committee was

sitting on Fire-proof Buildings, the Commissioners being Sir Henry de la

Beche, the eminent geologist, and Mr. Thos. Cubitt, the well-known builder,

of Piinlico. These gentlemen, hearing of Mr. Fairbairn's investigation of

the Oldham accident, requested him to give evidence before them, which he

did; but no report or publication of the proceedings of the body can be

found.

A year or two afterwards he followed up the

subject by a paper ' On some Defects in the Principle and Construction of

Fire-proof Buildings,' read before the Institution of Civil Engineers, April

20, 1847, and published in vol. vi. of their Minutes of Proceedings. It was

founded on an examination of another cotton-mill in Manchester that had

fallen shortly before; and the paper pointed out that in this case, as at

Oldham, the iron beams were far too weak for the load they had to sustain.

Some years later he published a book on this

subject, which will be noticed in a subsequent place.

In 1847 Mr. Fairbairn was applied to by the

authorities of the city of Basle to design a bridge for crossing the Rhine

at that place. He accordingly made drawings and estimates of a bridge on the

hollow girder principle. It was to be in several spans each 1U0 feet long,

and was to cost 34,000/.

It does not appear, however, that anything

further resulted from this offer.

In the second chapter of this work allusion has

been made to the large use of iron bridges consequent on the great extension

of railways that took place soon after 1840. Some of these structures proved

faulty on trial, and some serious accidents occurred from their giving way.

The conditions were to some extent new, on account of the vibrations and

concussions to which the bridges were exposed by the passage over them of

heavy trains, often at high speed ; and doubts were felt as to the state of

engineering knowledge in regard to their design. This attracted the

attention of government; and in August 1847 a Royal Commission was appointed

'for the purpose of enquiring into the conditions to be observed by

engineers in the application of iron in structures exposed to violent

concussion and vibration. The Commission consisted of Lord Wrottesley,

Professor Robert Willis, Captain Henry James, R.E., Messrs. George Rennie,

William (afterwards Sir William) Cubitt, and Eaton Hodgkinson, and Captain

Douglas Galton, E.E., was the Secretary.

The Commission collected much information and

examined many witnesses, among whom Mr. Fairbairn, from his large practice

in ironwork, was one of the most prominent. He gave-evidence in November

1847, describing iron structures he had designed, stating his experience in

regard to the properties of iron, and the mode of using it, and explaining

his views as to the forms of iron beams, Ihe mode of testing them, the

influence of vibration, &£f&c. In a subsequent communication he gave useful

suggestions for experiments, and furnished full particulars of the

investigations he had made for the Britannia and Conway Tubular Bridges. Ihe

Commissioners made their report in July 1819, in a Blue. Book which is well

known, and often quoted when the properties of iron are in question.

In January 1849 Mr. Fairbairn read before the

Institution of Civil Engineers a paper ' On Water-wheels with Ventilated

Buckets,' which was afterwards published in vol. viii. of their Minutes of

Proceedings. It contained an account of an invention originally introduced

by him many years before, and which has been always admitted to be of great

value.

In the course of manufacture of waterwheels for

Catrine Bank and elsewhere, at an early period of his mechanical practice,

Mr. Fairbairn had the opportunity of carefully studying their action and of

making many improvements, the most important of which was an arrangement for

what was called the ' ventilation of the bucket.' It had been found that

difficulty had existed in getting the water to enter the buckets freely,

particularly when the opening was contracted, as was often necessary. This

difficulty arose from the fact that the air iti the bucket could not get

away to make room for the water. Mr. Fairbaim saw that from this simple

defect many large water-wheels lost an important proportion of their power;

and he took steps to remedy the evil. His mode of doing so was .simply to

construct a small passage opening upwards out of the bucket, by which, when

the water entered, the air could rise and get away, and so leave the whole

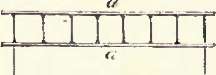

content free for the reception of the water. The following section of the

buckets (taken from the published paper) will illustrate at a glance the

nature of this simple and elegant contrivance. The arrows show the course of

the escaping air.

VENTILATED BUCKETS FOR WATER-WHEELS.

It should be added that the same improvement

which ensures the quick admission of the water also facilitates its quick

discharge (an object also of much importance) by allowing the air to enter

again into the bucket.

The first wheel constructed on this principle

was at Handfortb, in Cheshire, in 1828. No patent was taken out for the

invention; but the contrivance so much improved the action of the wheels as

to acquire great notoriety, and to bring large orders to the firm. The

arrangement was subsequently improved and extended to various classes of

water-wheels, and full descriptions are given in the paper.

The following matters, of more personal

interest, may be noticed in this place for the purpose of preserving the

chronological arrangement of events in Mr. Fairbairn's life.

lie occasionally took pupils into his

manufactory, which, from the care and knowledge with which it was laid out

and worked, formed an excellent school for mechanical engineering. One of

the young men so taken, the son of the celebrated founder of Mechanics'

Institutions, Dr. Birkbeck, was also a frequent visitor at Mr. Fairbairn's

house. The following extracts from the father's letters may be interesting

:—

38, Finslmry Square, April 13, 1840.

Dear Sir,—On my visit to Millwall, I had a very

satisfactory conversation with yonr partner, Mr. Murray; and your kind and

liberal communication from Manchester has quite confirmed my favourable

impressions.

I have decided, quite with my son's concurrence,

that he should proceed to Manchester and enter your establishment there. I

really hope that he will render himself worthy of the opportunity which he

will enjoy of acquiring sound and varied practical information. He will, I

think and hope, be greatly interested in the construction of the beautiful

and splendid pieces of mechanism which must continually be in progress in

your establishment; one of the most extraordinary, I understand, in the most

wonderful school for mechanical invention in the world, the town and

neighbourhood of Manchester.

If I mistake not, judging from the kind and

rational remarks which you have made on the duties of young men destilled

for a liberal profession, my son will be very likely to enter with great

cordiality into your views.

I wish it was in my power to accept your

invitation to visit Manchester; this is a pleasure, however, which must be

deferred until the weather is a little more settled, and until, by the

practice of taking exercise, not very convenient to me in winter, I may

acquire strength and activity enough to cope with the demands which

Manchester would make upon my curiosity and my exertion.

About thirteen years ago, on my return from a

hasty journey into Yorkshire, Westmoreland, and Lancashire, I spent one day

in Manchester. My friend Sir Benjamin Heywood kindly disposed of the

principal part of my day, in which of course the Mechanics' Institution was

not forgotten. If I once more return I shall be at your disposal in regard

to this interesting object, and many others since brought into operation.

With great respect, I remain, my dear Sir, Very

faithfully yours,

Win. Fairbairn, Esq. George Bikkleck.

38, Finsbury Square, January 18, 1841.

My dear Sir,—We all rejoice in the effects of my

son George's residence under your superintendence. His feelings are better

regulated in consequence of the influence of occupation, under kind and

friendly control, and he has acquired a taste for industrious pursuits,

which I am persuaded will benefit him through life. He speaks in the highest

terms of yourself and Mrs, Fairbairn, and the rest of the family. I had

formed, I confess, great expectations from this engagement, and it is no

small gratification to me to feel that I have not in any respect been

deceived or mistaken.

Dr. Birkbeck died in December of this year.

In September 1841 Mr. Fairbairn's daughter Anne

was married to his young friend Mr. J. F. Bateman, au alliance which gave

him great pleasure, lie was much attached to her, and from that lime, he

often spent the leisure which he snatched from business with Mr. and Mrs.

Bateman and their family, sometimes also accompanying them on tours and

excursions either on the Continent or in the picturesque- districts of Great

Britain.

The business connection of Mr. Bateman with his

father-in-law in some important works in Ireland has already been mentioned.

After that their communications on engineering matters were very frequent;

and Mr. Bateman's previous engineering education and scientific tastes

enabled him to be of considerable service to Mr. Fairbairn. Indeed for many

years there was scarcely any engineering scheme or scientific investigation

undertaken in which Mr. Bateman's assistance was not called in, until the

time when Mr. Fairbairn's own sons grew up, and were able to render him

efficient help in his business transactions.

In January 1846 Mr. Fairbairn's father died at

the great age of eighty-six. The following letter, written to his wife on

receiving the news, is characteristic:—

Millwill, January 17, 1814.

My dearest Dorothy,—I have this moment arrived

from Paris and received the announcement of my poor father's demise. It came

upon me unexpectedly, and although he had reached a good old age, yet I feel

the stroke most severely, and can scarcely reconcile myself to the change.

The last link which bound us to the last generation is now snapped asunder,

and the many events of my childhood, with the endearing attentions of my

good parents, rise up before me as fresh as on the days of their occurrence.

Poor old man! I used to listen to him with great attention, and always

admired his sound judgment, and above all his unflinching integrity, which

was never absent under whatever circumstances he. was placed. I shall always

cherish his virtues and look back with pleasure to the happy days I spent

under his roof.

I feel my heart fill now they are gone, and

although a father myself, I experience the weakness of a child at the

bereavement I have sustained. I have been up for the last two nights, but I

must move again by this evening's train to Leeds, and from thence join my

brother at Newcastle, in order to perform the last sad duties to my

excellent and affectionate parent.

Your very affectionate,

W. Fairbairn.

The following letter from an eminent but

unfortunate artist will be read with interest, and shows the character Mr.

Fairbairn had acquired for kindness of heart. It is no breach of propriety

now to allude to the circum stances of the writer, for they have been but

too clearly told in his published life.

14 Burwood Place, London, December 22, 1844.

My dear Mr. Fairbairn,—You once gave me hopes of

an order.

Shall I make a proposition? Frank goes up for

examination and his degree in a week or ten days, at furthest.

His fees are 15l., and his college bill 40l-.

14.s. 11d.=-56l. 14s. 11d.

I have brought him through all his terms but

this last, and if this last be not paid up, he is ruined and will not have

his degree.

I will paint you a small picture for that

amount, or for any portion you will advance me at once. You were kind to

Frank, and may feel an interest in getting him through.

I never broke my word about a picture in my

life. Close at once and you shall have an ornament for your house.

I hope you and Mrs. Fairbairn and boys and all

are well.

Mrs. and Miss Haydon's kind respects.

Yours truly, B. R. Haydon.

Mr. Fairbairn endorsed the letter: ' Answered

February 15, with an order for a picture, value to be 30/.'

Poor Haydon did not break his word. One day,

about the middle of June 1845, he called at the house, in London, of one of

Mr. Fairbairn's relatives, and left au unfinished sketch in the hall, giving

a hasty message for its care. On the 22nd of the same month he shot himself

in his painting-room.

The picture, the subject of which is ' Christ

before Pilate,' is still in the possession of Lady Fairbairn.

The pride Mr. Fairbairn took in his long

friendship with George Stephenson has already been noticed. The following

letter is curious, when it is recollected that at this time the two men's

ages were fifty-eight and sixty-six respectively:—

Taptou House, January 5, 1847.

My dear Sir,—I have only this day received yours

of January 1.

It will give me great pleasure to accept your

kind invitation to Manchester when you return from Ireland. Should I find it

convenient to do so, I will inform you in due time. In the meantime let me

wish you and Mrs. Fairhairrn many returns of the season.

Now for the challenge to wrestle. Had you not

known that I had given up that species of sport, you durst not have made the

expressions in your letter you have done. Although you are a much taller and

stronger looking man than myself, I am quite sure that I could have smiled

in your face when you were laying on your back! I know your wife would not

like to see me do this, therefore let me have no more boasting, or you might

get the worst of it.

Notwithstanding your challenge,

I remain yours faithfully,

Geo. Stephenson. |