|

"Are these the rocks of

Naisi? Is this the roar of his mountain stream?"

"I will go towards that mossy tower to see who dwells there."

Cameron.—Your

tale is interesting, but notwithstanding all, I believe the greatest

resident of the fort to have been Fingal, and I will give you my

impressions. Meantime I may say that you have done your best to tell

the story fairly, and I cannot complain, but we here make the heroes

the real sons of the man Uisnach, who belonged to this place.

Besides, we have here a tradition that an Earl of Ardchattan went

over to Ireland and ran away with an Ulster princess, and lived up

at Ruadh nan Draighean. Then we call the heroine Darthula, and

several places are called after her. On the whole, I think you have

the best grounds for your version historically. The incidents may

have happened before Fingal's time, and no one can deny that the

names have a most tenacious hold of the land here. Besides, they

occur in no other place as they do here, so that we are not

distracted by contradictions. Everything is natural but the Druid's

wrath and power ; these are the only things in the story in the

least exaggerated so far as internal evidence goes. I find, too,

that the landing at Ballycastle on the return to Ireland is well

remembered by tradition. A rock there is called Carraig Uisneaclz.

The local pronunciation rather corrupts one name, and the lady is

called Gardrei, and it is said that the men were murdered near the

rocks, and that she was confined in Dunaveny Castle not far off.

Ballycastle is directly opposite Raghery Island, to which Deirdre

advised the band to retire. This removes the scene from Armagh where

the king was, but it might have been placed there for effect. In any

case, it seems a true story, and I confess the name "the sons of

Uisnach " is rather in favour of their having come from Ireland.

Uisneach is a central place in Ireland, and is in no way to be

attributed to Scotland. Still, I consider that Fingal lived here

after, if not before that clan, and he is by far the greatest

character, so I prefer to connect the Dun with some one of fame.

Loudoun.—He

must have been a good Scot that made those poems, and he must have

loved this land. I should think Deirdre's poem the first recognition

of the beauty of the Western Highlands. Our forefathers in the

Lowlands had no idea of it till of late, they seemed afraid of the

hills. The writer admires the sons of Uisnach. He has really not a

word to say of the sons of Alban. He seems quite impartial. He

admires the people of Ireland and the land of Alban. I do not say

Scotland ; the time claims to be before that name was used here.

Fingal's claim is not clear to me at all.

Margaet.—Darthula

is a far more beautiful name than Deirdre. I wish you would use it.

O'Keefe.—In

Ireland it is never used. I do not know well its authority, but

there is some for it.

Margaet.—Darthula

must have been a kind of Helen.

Loudoun.—Yes;

a beauty about whom nations fought, places at least quite as

populous as Attica and the Troad probably; but not quite so far away

from Ireland as Troy from Mycenae, although the latter distance is

not much above two hundred miles. Deirdre was the Helen of the

Celts, and people still say "as beautiful as Deirdre." Do you remark

how true and how tender she was?—truer than any ideal of Greece, and

wise and thoughtful. She seems to have been a very noble character,

and names of places do not grow from triflers. Even great beauties

may have character. We shall meet her again.

Cameron.—You

must know I am not so anxious to exalt these sons of Uisnach. I

still prefer to give the Castle of Berigonium to Fingal, and to call

it by the ancient name of Selma. I see Fingal at the feast of shells

on the top of that mound, and I see him stalking down the hill with

his great spear. I can imagine him meeting heroes, whom he kills on

the plains beneath, and seeing ghosts coming down from the Appin

hills or from Morven, for many a dark view have I seen of both.

It may appear strange

that the name of the Fingalian hero should not have been distinctly

preserved in connection with the palace or city. The latest poems

ascribed to Ossian may serve to throw some light on the subject,

particularly the piece called "Losgadh Theamhra" or the burning of

Tara. The burning of the home of his ancestors is particularly

referred to and lamented in the sad story of his old age. He himself

was the last of his race, and Ossian an deigh na Feinne, "Ossian

after the Finn," has become a proverb. He was an old man,

remembering great days. The description of Teamhra given by the

poets makes it exceedingly probable that Dun MacUisneachan (Selma or

Berigonium) was the place meant, and referred to, and tradition

concurs with the poet's account of the city and palace. Dun Valanree,

the king's town, near the chief Dun, is a name to be remembered in

considering this, the ancient capital Selma.

O'Keefe.—I3efore

you give too many arguments let me answer those you have suggested.

According to our history, Finn lived nearly three hundred years

after Conor MacNessa and the Uisnach family. It is most natural,

certainly, to take the name from the earliest, but only when in want

of more famous men. If Finn, or Fingal, as you name him, had lived

at this Dun, his superior fame would have put the other aside,

although not quite of necessity. I do not know Tara as a home of

Finn, but of the kings of Ireland. Conor lived in the time of

Christ.

Cameron.—Mr.

Skene says that the names Cuchullin, Deirdre, and sons of Uisnach,

were connected with vitrified forts.

O'Keefe.—I

fear the connection is accidental. If in two or three cases it

exists, it only shows the style of building at the time and favours

no side, but the names of the family are connected with various

places, and these chiefly not forts at all. Deirdre's Grianan is a

rock. Eilean Uisneachan had cottages made of boulders on it. The bay

of Naisi or Camus Naois has no old building, and so of the wood.

Cameron.—Still,

some of the Fingal family have left their name in this locality. We

have Tom Ossian near Barcaldine; that was the favourite seat of

Ossian.

O'Keefe.—I

fear this is not well founded. There is also Carn Ossian at

Achnacree mor, and at least three urns were in it. Not that this

would prove that Ossian was not there, but it was not sacred enough

to be devoted to him alone. Besides, we have several graves of

Ossian, and that settles the point so far.

Cameron.—Frequent

allusion is made as I remember to the burning of the ancestral home

in Ossian's lament for the Fingalians. It may be that the burning of

the palace and the extinction of the Fingalian dynasty were

remembered in connection with the contest between the kingly and

priestly power. There might be a feeling of awe connected with these

two events, which would prevent the name of any one of them being

associated with the scene of the disaster, in which fire was the

means of reducing the palace to ashes and the city to ruins.

Selma, which means

fine view, had the same meaning as Teamhra, the latest name used

by Ossian in describing the ancient palace.

Beregone and Dun

MacUisneachan are other names, both of which have been used down to

modern times. The locality is clearly indicated in the description

of other places in the vicinity, such as Lora or Lora nan Sruth—now

called Connel, and the favourite Cona in Glencoe, where Ossian spent

the evening of his life and composed his most touching lays. The

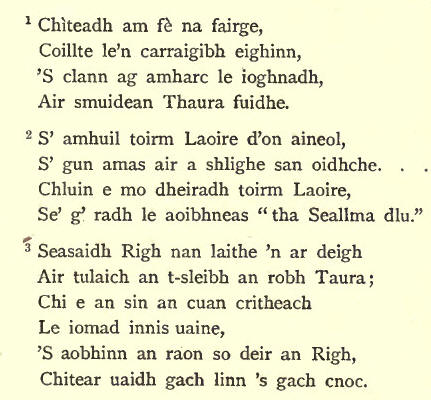

following passages are equally applicable to Selma and Teamhra:-

"In the unruffled

sea, with ivy covered rocks, might be seen children gazing with

wonder at the smoke of Taura reflected in the deep." [1]

Teamhra must have

been very close to the sea when its smoke could be reflected in the

smooth water.

"It is the sound of Lora to the stranger groping his way in the

dark. . . . He hears at last the sound of Lora, and exclaims with

joy `Selma is near.' [2]

Again, "A king of

future times shall stand on the slope of the hill, once the site of

Taura. He can see in the distance the trembling ocean with many

green islands. From this lonely spot," exclaims the king, "may be

seen many lions and hills. [3] The burning of Tara is minutely

described. Fingal was at the time on Ardbheinn, and was

forewarned by the

doleful tones of the harp. "The harp had a doleful tone like the

moaning sound heard on the lonely hill before the coming of the

fierce storm." "We arrived late at the palace. The flames were

flickering low, the house fallen to the ground, and smouldering in

the spent fire." "There were in the hall a hundred sets of bows and

arrows, a hundred sets of shields, also a hundred bright coats of

mail, as many glittering swords, a hundred dogs, and a hundred

bridles." Wives, children, and young maidens were among the ruins.

"They were surpassing fair, but the flame laid their beauty low."

Dun Lora was the name

of another fort near Luath Shruth on Connel. It is referred to by

Ossian in the third book of Temora, where Fingal asks, "Where is the

chief of Dun Lora? ought Connal to be forgotten at the feast?"

Loudoun.—I

shall not enter into the controversy about Ossian, although my mind

is quite clear on the subject, but this I may say, that even with

the greatest belief in Ossian, Dr. Clerk, who edited the poems, does

not see any proof that Selma was at Dun Mac Uisneachan. In a word,

the names of the Uisnach family are inseparable from Loch Etive. The

Fingalians are everywhere, and have no special connection with this

place.

O'Keefe.—I

gave you the groundwork of an epic of Deirdre. I leave Ossian and

Fingal to others; they certainly come later if our records are of

any value. We need not dispute therefore. I may quote, however, from

Sir John Sinclair's edition of Ossian, 3rd vol., p. 269, in a note

to Temora, Duan V. Speaking of Lora, he says, "There is no vestige

of this name now remaining, but a small river on the north-west

coast was called so some centuries ago." The phrase "north-west

coast" is vague, and can hardly have meant this neighbourhood. And

yet in the same edition the name Lora is given also to the hill

Ledaig. In the same book, Alex. Stewart, giving his evidence for

Selma, says that the white beach answers exactly the present aspect.

Now the beach is not white when compared with other beaches I could

speak of.

Cameron.—\Nell,

take that passage

"O Snivan of greyest

locks,

Go to Ardven of hills,

To Selma surrounded by the wave."

O'Keefe.—Who

Snivan was we do not know, but we know that the rock in question is

not surrounded by waves. It is at the head of the bay. Ardven

applies to many places, and less to our Dun than to Dun Valanree.

Then we have, "The

king . . . . will see Cona's pebbly streams rolling through woods

abounding with herds; he will see at a distance the trembling ocean

abounding with many green islands." This seems conclusive against

our fort being meant; we cannot see the streams of Cona or any other

streams from it, they are far away. We can see the ocean, but no one

would say it was the distant ocean, since one can scarcely creep

between it and the rock. True, we can look afar off, but we cannot

see many green islands; although that may be allowed, as we do see

islands. It is not a distinctive account that can prove anything.

The description is

not exact enough to enable us to identify any time, place, or thing.

Of course, if the description of the spot were exact I should then

attack the authorship.

Cameron.—Let

us look at another poem; it is from the Dean of Lismore's book, the

manuscript of which is assuredly above three centuries old

:—(English, p. 20 ; Gaelic, p. 15.)

"All of us rose up in

haste,

Except Finn of the Feinne and Gaul,

To welcome the boat as it sped,

Cleaving the waves in its course.

It never ceased its onward way

Until it reached the wonted port.

Then when it had touched the land,

The maid did from her seat arise,

Fairer than a sunbeam's sheen,

Of finest mould and gentlest mien."

Dr. M'Lachlan's

translation does not mention the waterfall, which must be Lora,

while Sir John Sinclair's edition takes notice of the peculiarity of

a vessel crossing a fall.

O'Keefe.—The

poem in Dr. M'Lachlan's book does not speak of crossing the fall,

but then it depends on the reading. Is it thir an eas or

than an eas. The first would be the land at the fall, the second

over the fall, but it does not matter which, as the poem distinctly

says that it was at Easruaidh, where Finn was living in a tent: so

it was not near his halls. There are two "Essaroys," but neither fit

well the situation. Mr. Stewart seems to wish to make Lora the same

as " Cona of Cairns," but this appears to me to strain the meaning

very much.

Cameron.—Perhaps

you are too precise about Fingal's tent, but I cannot explain

Easruaidh. If you read on in that same poem, you will see the death

of the fierce Daire, who was killed at the landing; and I was

inclined to look at one of the Cairns at Connel as being placed over

him. You remember the passage (Dr. M'Lachlan's translation)

"We buried him close

to the (water) fall,

This noble, brave, and powerful man,

And on each finger's ruddy point

A ring was placed in honour of the king."

I should like to

distinguish the Cairn of Daire. He at least had no connection with

Macpherson, to whom you are always objecting.

O'Keefe.—I

should also be glad. I never r remove the traces of history or

romance from a place without regret. Still, the evidence is wanting

for this point also, but interest enough remains, for these are "the

rocks of Naisi," although, that the poet alluded to them when he

spoke of Selma, no one, in my opinion, can tell, and even if he did

allude to them, the question would still remain, who was that poet?

Cameron.—I

think you difficult to persuade. Listen to me again. Let us look at

"Carthon" together. I may say, as it is said there, "The murmur of

thy streams, O Lora, brings back the memory of the past. Dost thou

not behold, O Malvina, a rock with its head of heath? Green is the

narrow plain at its feet ; there the flower of the mountain grows,

and shakes its white head in the breeze; the thistle is there alone,

shedding its aged beard. Two stones, half stink in the ground, show

their heads of moss. The mighty lie, O Malvina, in the narrow plain

of the rock."

We had, not long ago,

the two stones standing in the field below the Dun to the south ;

now only one remains. We have the stream in Connel falls, the heath,

and the remains of the famous dead. Happy, I doubt riot, was the

feast on that lonely hill, even when the heroes round Fingal sang of

the death of Moina, which happened long before, when Clessammor was

obliged to flee in his ships from Balclutha (Dunbarton). But a

terrible memorial of that struggle soon appeared. In the morning a

mist rose from the linn. "It came in the figure of an aged man along

the silent plain. Its large limbs did not move in steps, for a ghost

supported it in mid-air. It came towards Selma's hall, and dissolved

in a shower of blood." Soon the sun rose, and there was seen a

distant fleet. The ships came like the mist of ocean, and the youth

poured upon the coast. The chief moved towards Selma, and his

thousands moved behind. Fingal was ready to receive him, and drew

this picture, in language very gentle in sound, but involving a

terrible threat: "How stately art thou, Son of the Sea; ruddy is thy

face of youth, soft the ringlets of thy hair, but this tree may

fall, and his memory be forgot! The daughter of the stranger will be

sad, looking to the rolling sea; the children will say, "We see a

ship; perhaps it is the king of Balclutha." The tear starts from

their mother's eye. Her thoughts are of him who sleeps in Morven.

Behold that field, O Carthon! Many a green hill rises there, with

mossy stones and rustling grass; these are the tombs of Fingal's

foes, the sons of the rolling sea." A struggle began; the stranger

killed Cathul and Connal; and this reminds us of the name Connel

ferry. Can you not imagine Carthon standin- there, looking at the

next champion, and saying to himself, "Perhaps it is the husband of

Moina, my mother, whom I cannot remember, and who died in sorrow on

the Clyde. I have heard that my father lived at the echoing stream

of Lora." Clessammor, the father, refused to tell his name, and was

mortally wounded, whilst he himself killed his son. "Three days they

mourned above Carthon; on the fourth his father died. In the narrow

plain of the rock they lie; a dim ghost defends their tomb. There

lovely Moina is often seen; when the sunbeam darts on the rock, and

all around is dark, there she is, but not as the daughter of the

hill. Her robes are from the, stranger's land, and she is still

alone."

Ossian was sorry for

Carthon, and spoke thus in a song: "My soul has been mournful for

Carthon, he fell in the days of his youth; and thou, O Clessammor,

where is thy dwelling in the wind? Has the youth forgotten his

wound? Flies he on clouds with thee? I feel the sun, O Malvina;

leave me to my rest. Perhaps they may come to my dreams; I think I

hear a feeble voice. The beam of heaven delights to shine on the

grave of Carthon: I feel it warm around.

"O thou that rollest

above, round as the shield of my fathers, whence are thy beams, O

sun, thou everlasting light?" . . .

I cannot finish that

address; it is too beautiful to utter except when I am alone. Is not

the whole picture very fine; does it not describe the spot exactly?

Loudoun.—The

picture is fine, and I confess there is room for a new

criticism—esoteric—rather than one relating only to authenticity.

Still the scene would suit many places, and Cona is mentioned, which

brings great confusion—at least it is a favourite idea that it means

the stream of Glencoe. There is no name spoken of known on the

ground except that of Connal, and there is little said of him. But

you do not prove authenticity by proving that the writer had the

plain of Ledaig or any plain in his eye. The poems, which I call

Macpherson's, are remarkably atopic—that is, they seldom venture to

name a place that we can recognize, and my theory is, that, having a

desire to keep to the ancient legends and poems, but being only

imperfectly acquainted with the whole of the literature, he

preferred as much as possible indefinite scenes. All are vaguely

described. The new ordnance map has been formed by the advice of an

enthusiast of Ossian. These maps will be used as evidence, but as

such they must be put aside whenever they use a name which has been

first applied to a place since Macpherson wrote. This must be

remembered. It grieves me to say a word against the belief in the

ancient Ossian having written or spoken the words quoted ; since you

so strongly hold it, I would willingly do so also. Still the change

of authorship does not alter the intrinsic character of the poem. I

have given some time to the subject, and carefully examined it—with

the aid, of course, of the writings of J. F. Campbell (Campbell of

Islay) and others, and all doubt or hesitation is removed. Before my

careful study I was in difficulties, and feared to decide against

Macpherson. When you urge me strongly to believe, I feel it

painfully, and I say like "Clessammor with a tear," "Why dost thou

wound my soul ?" |