|

Cameron.—I think

we might go to Tyndrum by train. It will be pleasantly strange to

rush up such a waste as Glen Laogh in such a bird-like fashion. Once

I went up by coach, but the horses grieved me, and I could not see

the river as it rushed down its gorge. True, I saw the wilderness,

and it pressed upon my mind. Surely the Sahara can scarcely be mire

desert, but it is different; Sahara has not even the winds, or they

are rare as well as dusty, and even the demons of the stones have

deserted the place. Here they rage on the hills, and Cailleach Bheir

moves from mountain to mountain.

Margaet.—How

dreadful to skim over the precipitous banks of this stream. No human

being could see it in its natural state before this railway began to

play upon its precipices, and here we take the way of the crows.

They used to tell me that it was a terrible pass, only few people

could climb it in winter, and none of the farmers could go up and

down in a day with their carts unless these were empty. But here we

are flying up and we shall alight in half an hour. The fables of

childhood become silly, and its wonders turn to nothing even to the

young.

Loudoun—It is

not quite so. The fables of childhood do not become silly ; they

never have been so important as now; we neglected them, and now men

of learning treasure them and learn philosophy and history from

them. Let us learn the same from this road. In the memory of man it

was a difficult passage for any one, and very hard for a horse with

a burden. For a generation the road has been fair, but steep. I

remember when it was a hard journey to Tyndrum, except for a good

hill walker.

Cameron.-It is

a strange valley this. You see it is a collection of heaps which

exist in thousands, masses as if left by melting ice; but they might

have been made by local shower-water. The old poem which was before

quoted about the sons of Uisnach calls it the glen of straight

ridges:-

Glen Urchain! O Glen

Urchain! (or Glenorchy! O Glenorchy!)

It was the straight glen of smooth ridges

Not more joyful was a man of his age

Than Naoise in Glen Urchain. —Skenes translation.

This at the upper

part is not properly Glenorchy, which is more strictly the branch to

the north; but the stream from here runs into the Orchay or Urchaidh,

and Glenorchy is the wider name that runs down along the side of

Loch Awe. There is no manageable road up through the real Glenorchy.

This is one of the

reasons why I brought you to Dalmally. You see one of the hunting

places of the Uisnachs, and you learn that it is still as it was of

old, leaving out the road and railway, if you can manage to think of

it so.

We are at Tvndrum,

Tigh'n druim, the house on the ridge. A dreary house it was once;

now there is a fine hotel. Even manufactures have tried to settle

here, and in that little hole up on the side of the hill it is said

that the last :Marquis of Breadalbane spent sixty thousand pounds

looking for lead, and perhaps he spent somewhat more, trying to make

vitriol outside with the minerals got from within the hill. Our ride

being short, we shall need no rest here, but we shall again take the

private rather than public conveyance ; we must spend some time on

the way.

We drive along first

an unpromising wild road, and seem to be rushing among pathless

hills, but soon we go down to the plain, and we need not fear, since

everywhere the roads are good, and you see that our horses are

strong. As we move down we come on an unexpectedly open space, and

whilst the wild hills of the deer forest of the Black Mount are on

the left, we come on the famous Ben Doran to the right.

Margaet.--It

is big but not beautiful, sloping and not varied.

Cameron.—Yet

it had power to produce a fine enthusiasm in Duncan MacIntyre, as

you will see if you read Professor Blackie's translation of his

poem. This to first appearance rather smooth and stony side is long,

and if the other is equally so it is a large place not easily passed

over by men, except the best of walkers. But listen to MacIntyre and

you will hear that behind that too flat side, and perhaps upon it,

there are numerous dens where deer can hide and men may be lost.

BEN DORAIN

HONOUR be to Ben

Dorain

Above all Bens that be

Beneath the sun mine eyes beheld

No lovelier Ben than he;

With his long smooth stretch of moor,

And his nooks remote and sure

For the deer,

When he smiles in face of day,

And the breeze sweeps o'er the brae

Keen and clear;

With his greenly-waving woods,

And his glassy solitudes,

And the stately herd that fare,

Feeding there;

And the troop with white behind

When they scent the common foe,

Then wheel to sudden flight

In a row,

Proudly snuffing at the wind

As they go.

"`Tis a nimble little

hind,

Giddy-headed like her kind,

That goes sniffing up the wind

In her scorning;

With her nostrils sharp and keen,

Somewhat petulant, I ween,

'Neath the crag's rim she is seen

In the morning.

You will never with

your ken

Mark her flitting paces when

With lightsome tread she trips

O'er the light unbroken tips

Of the grass;

Not in all the islands three.

Nor wide Europe, may it be

That it step so light and clean

Hath been seen,

When she sniffs the mountain breeze,

And goes wandering at her case,

Or sports as she may please

On the green;

Nor she will ever feel

Fret or evil humour when

She makes a sudden wheel,

And flies with rapid heel

O'er the Ben;

With her fine and frisking ways

She steals sorrow from her days,

Nor shall old age ever press

On her head with sore distress

In the glen.

III

My delight it was to

rise

`With the early morning skies,

All aglow

And to brush the dewy height

Where the deer in airy state

Wont to go;

At least a hundred brace

Of the lofty-antlered race,

When they left their sleeping place

Light and gay;

When they stood in trim array,

And with low deep-breasted cry,

Flung their breath into the sky,

From the brae;

When the hind, the pretty fool,

Would be rolling in the pool

At her will:

Or the stag in gallant pride,

Would be strutting at the side

Of his haughty-headed bride,

On the hill.

And sweeter to my ear

Is the concert of the deer

In their roaring,

Than when Erin from her lyre

Warmest strains of Celtic fire

May be pouring;

And no organ sends a roll

So delightful to my soul,

As the branchy-crested race,

When they quicken their proud pace

And bellow in the face

Of Ben Dorain.

IV

For Ben Dorain lifts

his head In the air,

That no Ben was ever seen

With his grassy mantle spread,

And rich swell of leafy green,

May compare;

And 'tis passing strange to me,

When his sloping side I see,

That so grand

And beautiful a Ben

Should not flourish among men,

In the scutcheon and the ken

Of the land."

Margaet.--That

is certainly beautiful enthusiasm, expressive of poetic joy. Is it

really a good translation, or is the poem of Professor Blackie's

making altogether?

Loudoun.—I

have been particular to ask, as I am not able to judge of the style,

and every one says that it is well done, and not superior to the

original.

Cameron.—I am

a Highlander, and I prefer the original, still I think it well done

and wonderfully exact. I have asked our minister also, who is a

cultivated man, and can compare the two version, and he thinks it

very well done, expressing the original very closely.

Willie.—I see

no room for deer. Let us run up a bit and see.

Cameron.—Well,

you may run up this lower part. There must be many smaller glens,

ridges, precipices, brooks, and shelter for deer on the great mass

of this hill ; we see only the face here. Behind is a great

region—the glorious region to which only strong men can attain, and

which made a poet of the gamekeeper, and which even we who cannot

attain delight to revel in so far as he can enable us. Let us take

some lunch until Willie returns.

O'Keefe.—I

shall sleep among the heather or look up to the sky; I like to see

the clouds, they are always changing, growing, and diminishing, and

the edges are in everlasting motion, and those which go fast are the

most changeable.

Willie.—Here I

am after a good run; but I could, after all, find nothing without

much more running. It would require a fox or a deer. There is a far

beyond.

Cameron.-In

old times there were plenty of foxes, and I daresay there are some

here still. They have been killed to introduce sheep, and this habit

annoyed MacIntyre exceedingly. Listen to his praise of foxes. (P.

184, Dr. Blackie.)

A SONG OF FOXES.

Ho! ho! ho! the foxes!

Would there were more of them,

I'd give heavy gold

For a hundred score of them

My blessing with the foxes dwell,

For that they hunt the sheep so well;

Ill fa' the sheep, a grey-faced nation

That swept our hills with desolation

Who made the bonnie green glens clear,

And acres scarce, and houses dear;

The grey-faced sheep, who worked our woe,

Where men no more may reap or sow,

And made us leave for their grey pens

Our bonnie braes and grassy glens."

MacIntyre lived when

sheep-fanning on the hills was new, so late is the custom. In old

times deer and foxes and free hunting made a happy ground for

undisturbed men.

Now we are come among

deer foresters and stalkers, men who make thousands of acres desert

for the purpose of shooting. Much of this is wilderness. There is a

house in that wood, and there is an inn at Inveroran, and you see

some trees called a part of the Caledonian Forest, but, so far as I

know, all interest here is in the wildness and the mountain and the

deer.

Loudoun.—And

why not? Did we leave home to see more chimneys or houses? You may

travel in England through many counties and scarcely see variety of

scenery perhaps some difference, not much, in building houses or

working farms: here you have land, crops, and animals all different

from those where we started, and it is a new world. I think it worth

while to lose the sheep for the variety of the sight, even if we are

not the favoured ones who possess it. Even the owner may see it

little. Look at the Moor of Rannoch, a desert with danger from

water, a place without a track, which a man cannot well cross in a

day if he does not know the road. There is no sitting down on warm

sand when you are tired, confident in the permanence of the heavens

above you. You rather feel sure of a constant perfidy. You need

shelter, but there is none until you come to King's house, which

stands at the top of Glen Etive and Glencoe looking down each of

them.

Cameron.—Nowadays

we have some chance of being fed and lodged; that is, one may rely

on the people if the house is not too full.

I took care, by

writing; otherwise we might have been obliged to drive down to

Glencoe and so lose our object. Still we shall go down, a little

after dinner and some rest.

O'Keefe.—What

a wild run to the top of Glencoe ; at this precipice we may stand

and look down. It is a beautiful defence against outside men. These

walls are magnificent, and were it not for this road I could hold it

with one to a hundred. Down there men might live in peace so long as

there were sheep to eat.

Sheena.—I

shudder at that awful hill ; black caves on the front looking over

precipices, and wild clouds covering summits making the passes above

as dark as night. What is the name of it?

O'Keefe.-The

forester here told me it was Aonach Dubh. Aonach, I suppose, is

lonely, lonely, and is a name given to a hill, a wild poetic name

suiting the solitary spots and the wonders on it. Many people at one

time never can be on these hills. Dubh is black. "Black and lonely"

is a fine name for it, and behind where you saw an opening there is

a pass from Loch Etive to Glencoe, which is called Larig Oillt, the

Pass of Terror. It expresses exactly the feeling you seem to have

had when looking up to the black clouds moving among the broken

rocks and darkening the way.

Loudoun.—I

once asked the forester here about this pass of Terror, and he, you

know, looks after the deer, and knows the rocks as well as they do;

but he told me that the name was Larig Eild, the pass of the hinds,

and that it related to the habits of these animals.

Margaet.—I

prefer Mr. Clerk's view; besides he has studied Gaelic. The result

is more poetical, and I feel that we have hit on a wonderful spot ;

besides the word is used elsewhere. This at least is a view of

Glencoe new to me, and as we look down on that awful gulf in the

darkening night, I wonder that our fellows live there and not a

colony of mysterious forms. But there is mystery enough, and a deed

of moral blackness has made the whole more famous than even nature

has done with time and violence.

Cameron.—Let

us return. The hotel stands more in the mouth of Glen Etive than

Glencoe, and Glen Etive means the wild or terrible glen. But we must

not leave Glencoe without looking at the Cona, the favourite of

Ossian, whose harp is called the voice of Cona, on the banks of

which he was born. You know I believe in the Ossian published by

Macpherson as the real ancient Ossian, and often he must have hunted

here and ranged among these hills.

Loudoun.—We

shall not dispute here; but we can all admire this wonderful

hill—this conical mass between the two glens—this Shepherd of Etive

as it is poetically called, looking for ever down to the loch beside

his companion opposite. They both look also over the moor of Rannoch.

Wilson has made a beautiful photograph of one. When I was proposing

to go down Glen Etive, the landlord of the hotel doubted the

propriety of allowing inc a horse, because the streams came down

with such violence on rainy days, and the day was threatening.

However we ran down and up, the foaming torrents from the hills

softened into wide streams flowing over the roads, which had no

bridges and were liable to be swept away. The two hills are very

steep, and look as remarkable here as they do at a distance; whilst

this one, connects the two glens, it also unites Gaelic, Greek, and

Latin, the name of shepherd being nearly the same in both. The

Greeks had their boukolos, and Virgil wrote his Bucolics, and here

we have our buacleaill—all one word we may say. But more exactly the

word does not mean shepherd either in Greek or Gaelic, but cowherd,

and bucolics "relates to cow herding," and in Gaelic the word is

used for general herding.

Cameron:—Now

that we have come out of the dark glen and the clouds have cleared

away, it is not quite dark, and I care not to go into the house; I

will go up to my friend the forester, about a mile or more on the

Inveroran road, and see a true Highland house, built with comfort.

Who will come? The ladies may stay, and we shall expect some tea

when we return.

This road is farther

than I expected, and it is already darkening. There is only one

house, and it is on the right, and we cannot miss it. There is a

light, and the dog barks, and we must find our way among stones and

holes to the door. I doubt not that we shall find a welcome.

O'Keefe.—It

will be dark before you reach the house. Forester.—I am glad to see

you. I wish I could show you into my dwelling on the hills among the

deer; that would be something to look at.

Willie.—This

is novel enough. I thought you would live here in misery, with all

these dubs about and the road to the house made only by tramping

feet, and the house too looking very dark. But here you have a

blazing fire and a good lamp, and shooting and fishing tackle round

the wall, and plenty in the pots.

Loudoun.—Yes,

and happy faces about: why! here too is my friend from Barcaldine

come to chat with you.

Willie.-I like

to look up to the mysterious rafters. One wonders what may be there.

Cameron.—Yes,

you sometimes see the fowls roosted up there; but it is not so in

this house. It is a very bright and busy house to me coming from the

outside darkness.

Loudoun.—It is

certainly very different from the houses of the town workmen and far

superior, whilst the freedom of the occupation during the day makes

the life brilliant. It is living in the world instead of in a

prison. What say you, forester?

Forester—I say

that the work is hard, but grand. I am not a machine ; I must use

nay judgment daily, and that on no small scale, over many hills and

over many cattle. I am healthy, I am comfortable, and happy as most

men. Indeed I have my days of glorious feeling, and I seem to rise

with the mountains, although I sometimes may sink in bogs like those

on the moor; but these changes are like the face of nature.

Loudoun.—We

must go. Good night. I am proud of your acquaintance, and may we all

see you again.

Margaet.—You

must have had a (lark walk home. Why did you stay so late?

Loudoun.—There

is something very fascinating about the darkening in the Highlands.

I cannot explain it. I had some of tile feeling too in Switzerland.

It is caused partly by the hills looking upon you, but partly by the

peculiar shades. In a level country the land does not look at you;

you are alone; here you are stared upon by all around. It is a rare

sensation to us, and a luxury. To-morrow we have another new series

of sensations.

GLEN ETIVE.

Cameron.—And

now we roll down Glen Etive, with a Buachaill on our right and on

our left, although the latter mountain receives also a very prosaic

name. I am afraid of telling it. They call it Sron a creis (creesh),

and say it means the (promontory or) nose of grease or fat, because

it fattens animals so well. But this must be a very modern name—a

farmer's name. I prefer the I3uachaill (south).

The river rushes down

that deep ravine, which it has evidently made for itself, and we

pass along this precipitous bank, our lives depending on good

driving. Let its stand awhile and look at the deer on the opposite

side; they are quite undisturbed; no wanderers come here, except by

ones or twos, and a whistle will startle them. See!

Loudoun.—They

move off as soon as they hear. One might almost measure the speed of

sound by observing their movements; it is only a few seconds, and

certainly corresponds closely so far as I can judge of the distance

from us. They leap the brooks and sometimes seem to dance. One must

quote MacIntyre here, i.e. Donncha Ban, to describe the light

springing race. Such a solitude—not a farm-house, not a man, not a

sheep—and all this in Scotland. Each valley is a new country, and

there are thousands, or hundreds at least.

Margaet.---I

would look and rejoice if I could walk instead of staring,

continually down that terrible steep; when it ends I shall think on

the scenery.

Cameron.—We

now move rapidly down the hill and come into the depth of the

valley, where violent storms often meet, since here is a rapid turn

to the right, and numerous passages for air are made by the

irregular peaks. And see that one standing up like a piece of black

iron before us, the end of some Titanic spear. That is a memorial of

Deirdre, and I should not have asked you to cone had there not been

here something to remind you of the sons of Uisnach. It has two

names—Ben Cetlin or Kettelin and Grianan Dartheil, the Boudoir of

Darthula, a fantastic appellation, just as they call the rugged

hills of Loch Long the Bowling Green of the Duke of Argyle. But as

the latter indicates the nearness of the Duke, so the former does

the power of Deirdre. We must look on her and the whole tribe as

spending much time here and living on the deer. Kettel is a Norse

name, but this need not have a Norse origin; in Gaelic the meaning

might he quite different.

Loudoun.—We

are here in a basin, and it is hard to imagine these great hollows

filled with grinding ice. However, they are still subject to attacks

of water which washes down what little soil it may meet, and makes

way for the rolling of numberless pebbles and blocks. Much of the

valley below seems at times to be covered, judging from the breadth

of the gravel beds of the river.

O'Keefe.—Here

is another memorial of Deirdre—that field is called after her. And

so we hunt up our heroes in all the surroundings of Loch Etive.

Margaet.—I

wish some one would invent a way of describing a scene. I see and

feel, but cannot express.

Loudoun.—You

said this before; but there are many ways invented. The geologist

will describe this clearly, and have the surveyor to assist him; the

photographer will give you details the artist will come from it with

a memory on canvass of beautiful effects; but the poet, and he only,

can describe the feelings, and even he cannot exhaust them.

Margaet.—I am

not satisfied with any poet's description, it is generally a

collection of similes, or a number of unrealities which are raised

into being in his mind. Still I am not insensible to their beauty,

and I confess that Black has had great success in describing scenes

in this west in his Highland novels.

Cameron.—We

have passed only one house, it was at the bend of the glen, and was

a forester's. Now we come to Dalness or Dal an Las, the field of the

waterfall, and our poet Duncan Ban lived close to it for a while, in

a cottage of which a few stones are left. I cannot worthily

translate his verses, but we can look at the fine broad waterfall.

Here we may have

Wilson's poem, part of which I can give. He early found the beauty

of this valley. Let us imagine Professor Wilson addressing the deer

as he did here at Dalness. His own reading of it to his class was a

feast which seems to have fed his students with some of his

enthusiasm for the remainder of their lives. To be able to do this

is to live not in vain, and I am glad to say this for those who may

dwell too much on the author not being in the front rank of poets.

"Up, up, to yon cliff

like a king to his throne,

O'er the black silent forest piled lofty and lone

A throne which the eagle is glad to resign

Unto footsteps so fleet and so fearless as thine.

There your branches

now toss in the storm of delight,

Like the arms of the pine on yon shelterless height,

One moment, thou bright apparition, delay

Then melt o'er the crags like the sun from the day.

Down the pass of Glen

Etive the tempest is borne,

And the hillside is swinging, and roars with a sound,

In the heart of the forest embosomed profound.

Till all in a moment the moult is o'er,

And the mountain of thunder is still as the shore

When the sea is at ebb, not a leaf, not a breath

To disturb the wild solitude, steadfast as death."

Loudoun.—That

is fine, and if we do not see the same sight as he describes, he

having been himself a hunter on the hills, we are saved the labour

We like to see the wild passes that show themselves up these

pathless hills, and it is not strange that men from London seek the

life of the wild man here, as far as they can endure the imitation.

One ought to tame the deer and ride with them over the racks. We can

only follow them with the imagination, but slightly with the eye;

and we have the same want of satisfaction looking at, but unable to

follow, the salmon. It is a poor enjoyment eating him, as if we ate

his life and his poetic wanderings. Sport is partly a wish to

imitate, and eating the game is like a New Zealander eating in fancy

the strength and mind of his victim. It is a life of hope only, but

that is all our life; and he is not a sound lover of nature that has

no sympathy in sport.

The verses you

recited give a description of the forests which we may suppose

Deirdre alluded to in her song. There are few pines now at Glen

Etive, although nominally a forest for deer. The real meaning of

forest is not well known; if it comes from foris, without, out of

doors or outside the walls, then it is easily understood, and its

present use by deer-stalkers is more correct than the use by

tree-planters.

Cameron.—Another

rough road over streams, and in that terrible blast that comes

down—unavoidable! We must bow our heads and look up as we dare; now

we are at the height and can see the loch. We are at Druimachothais

(perhaps Druimachois, the ridge at the foot), and we shall dash down

to the small portion of plain to look for our boat.

Londoun.—Before

we leave this wondrous glen let us think of it so as to remember. It

is certainly one of the largest of the narrow glens of -Scotland. It

may be said to be 30 miles long, as the glen includes the lake. It

is certainly one of the deepest, and it has points as terrible as

those of Glencoe, in certain kinds of weather. It is larger, more

varied, and I imagine in storms almost as terrible. One wonders if

the ancient Celts really went up these hills; they speak of them and

of the clouds, but I do not know how high they wandered up the

peaks.

O'Keefe.—I

think they went up, but like the Greeks they do not leave us much

description of nature. I can give you a hunting scene from the Dean

of Lismore's book, which Dr. M'Lauchlin has translated. It is said

to be Ossian's, but the hunt is in Ireland on Sliabh nam ban fionn,

the hill of the fair ladies. Finn had a hunting dog called Bran, a

great favourite.

"Then Finn and Bran

did sit alone

A little while upon the mountain side,

Each of then panting for the chase,

Their fierceness and their wrath aroused.

Then did we unloose three thousand hounds

Of matchless vigour and unequalled strength

Each of the hounds brought down the deer,

Down in the vale that lies beneath the hill

There never fell so many deer and roe

In any hunt that ere till this took place.

But sad was the-chase doss-n to the east,

Thou cleric of the church and bells,

Ten hundred of our hounds with golden chains

Fell wounded by ten hundred boars;

Then by our hands there fell the boars,

Which wrought the ill upon the plain.

And were it not for blades and vigorous arms,

That chase had been a slaughter."

Book of the Dean of

Lismore, from the 3rd Poem.

The writer evidently

wishes to astonish the cleric by the amount of slaughter, and

expects the perhaps tame-like preacher to despise his own vocation,

before the glory of killing a thousand wild boars; but there is no

sentence regarding nature. The name of the hill may relate to nuns

with white dresses.

The Greeks were awed

by their great mountains, and stood in humility below. Did any one

of them ever climb Olympus or Ida? There is no wonder that men cower

before nature. They fear the darkness in the Highlands even now, in

the valleys, and much more a dark passage on the top of a black

clouded mountain.

Cameron.—I f

they did go up they did not live there much; that is, the people who

wrote did not ; but there is a class living even now on Mount

Olympus who rarely come down, and are almost entirely separate from

all others. Probably the same class lived with the same habits in

old times, unknown to the town-loving Greek, who knew little of

topography, and filled the wilds with mythic creatures. When we look

at that terrible pass on the western side of the Buachaill, the pass

of terror, at the time when the peaks are covered with black clouds,

and only a dark cave shows itself below, we have room for the wild

beings that were supposed to haunt this valley. You will see a

drawing of one of them in J. F. Campbell's Tales of the West

Highlands: there is a sketch of the wild creature of GIen Eiti (Direach

Glenn Eitidh, Mac Callain), he was also a Mac, the son of Colin. The

drawing, like the story describing him, gives " one hand out of his

chest, one leg out of his haunch, and one eye out of the front of

his face."

Margaet.—Is it

not said that even the Greeks worshipped mountains?

Loudoun.—I

don't know of any actual worship of mountains, but there is an

abundant appearance in the Greek mind of awe and feeling of mystery

relating to them.

Willie.—Now

this is a fine opportunity to tell a story as we stand under the

shed waiting for the boat.

O'Keefe.—As

you are near Cruachan, I will tell you a little tale from the Irish

Cruachan which is very different from yours. Near it was the palace

of the old Kings of Connaught, and it was not far from

Carrick-on-Shannon. The king and queen, Aillil and Meave, people of

whom I told you, who lived about nineteen hundred years ago, were

amusing themselves one winter evening with their followers, and they

were, I dare say, all bragging of their courage, when the king said

he would give his sword, a gold-hilted one, to the man who would go

out in the dark and bring a twig that was round the leg of one of

two men who had been hanged, and were still hanging. Nera was a

spirited youth and went, but on coming back he saw as it were the

palace on fire, and a host pf men met him who seemed to have

plundered it. They passed but did not take notice of him, and he

followed. They went to a well-known cave on the hill of Cruachan,

whilst Nera followed. But lie was seized and taken before the king

of the Tuatha De Danann. Now this cave was not visible to ordinary

human eyes, but Nera's had been enlightened and he could even show

the place to others. The king said little to him, but ordered him to

bring a bundle of fire-wood to th;; kitchen every day. On one of

these days he saw a blind man carrying a lame man and depositing him

near a fountain, and they had a dispute about the right spot. He

asked a woman, from whom the king had told him to take instructions,

who these people were, and she said they were guardians of the Barr

or Mind, a crown of gold which the king wears, and these people were

trusted by the king. The fountain was in the cave, and the Barr in

the fountain. Nera told this at Cruachan, and King Aillil obtained

the assistance of Fergus MacRoigh and the Ulster champions who had

left home because of the murder of the Sons of Uisnach, and

plundered the cave and obtained the golden diadem. Fergus, you know,

is one of our heroes. This was a mystery of the Irish Cruachan. The

story is from the book of Leinster, but taken from O'Curry and

Sullivan's 29th Lecture on Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish.

Margaet.—I am

unwilling to pass out of the glen proper on to the loch until I have

a good description of Glen Etive. It seems deep, lonely, secluded,

more than most, with curves that seem like passages to hide the way

into the great centre, where I can imagine a tribe living unknown

for generations; indeed, who knows this glen even now? The hills are

high, but except at the Grianan Dartheil, not so rugged as at

Glencoe, although the weird passages through the upper parts seem as

wild and ghostly.

Loudoun.—We

settle as before. GIen Etive must live in our feelings, and Deirdre

is the first person who is said to have discovered its beauty, and

to have recorded it in song. Perhaps you will object by saying that

the song is put into her mouth. It may be so, but I know of no other

author. No one of the outer world has come here to settle until

about five years ago, when that new house was built; the summer

fishers in the house above, which seems to be a very much improved

dwelling, if not a new one, may be another exception; but both are

very late comers. Now there is a steamer for the loch and a coach to

take people up the glen. It is not easy to go to the shore to find a

boat; one must sometimes pass the brook on the west side when it is

high. The bridge is only two planks covered with sods, far up and

reached only by passing through a bog. It is made for the shepherds;

or one may pass over half land half water, to the mouth of the River

Etive. It depends on the wind which side is best, but to-day there

is no wind, and we have good rowers waiting us, and a long boat by

the river side, and we may take the low road.

O'Keefe.—The

hills are desolate and rather too plain, I imagine, as we go down

the first mile or two.

Cameron.—This

view may be so, but on our left is Ben Starrive or Ben Starra,

which, by some mistake of a map, has been continued to be called in

guide books Ben Slarive, and that is a lofty mountain (3,519 feet);

it looks far down the loch, and on coming up it is often taken for

one of the Shepherds or Buachaills. It is broken up by streams, and

seems almost impassable for man as we see it.

Loudoun.—It is

surprising that the water can be even in a small degree salt here,

but there is sea-weed after 17 miles of a narrow passage against

roaring streams often driving down great floods. Surely it must

sometimes be quite fresh in the loch here?

Cameron.—Over

on our left, at Inver Guithaiseagan, is a small plain. There is a

wild story about a man who had robbed some place and hid his

treasure there, but forgot the spot, leaving the gold to lie there

still. I think that a probable enough story. Hiding gold was common,

and finding it used not to be uncommon, but this may long ago have

been found, and we have more interest in such a name as Inver

Draigneach, the point of the thunderer, where such rolling stones

are driven down from the mountain, making a great river of boulders.

They are at rest now, but we see them there lying ready to flow

along with the next sufficient stream.

Do not confound the

words for the rumbling noise like thunder with some of the terms for

Druid. The Gaelic language is full of traps that catch people in

mistakes.

O'Keefe.—We

are not in the wilderness; we have no sooner lost the sight of the

top of the lake than we meet with man's innovations; here is a

quarry, and a capital spot for our lunch.

Cameron.—Capital,

if it were raining and windy, but I know a better place than this

granite cavity. We come to it soon.

Margaet.—Then

from what you say, Mr. O'Keefe, there is a Cruachan in Ireland, more

famous in story than this one.

O'Keefe.--The

hill was more famous, but only because of the palace that was near

it. This one is so high that the lower portions receive names of

their own, but as we are still in Glen Etive in a sense, it occurs

to me that the reason that no really historical event is connected

with the deep and secluded and most habitable portion is because of

its inaccessibility. There never was a good road, and even the

inferior one is not old; besides there is no road up either side of

the loch even now, except for a good walker or rider, and no steamer

plied until lately, and it goes only for a little in summer. I

conceive Glen Etive about Dalness to have been a very safe place of

refuge, and a good hiding place for the Uisnach family at first, and

perhaps for many a generation of men who loved peace or who feared

detection. It is, therefore, said in the legend that Naisi and his

followers went to a wild part of Alba; and they would have been very

safe down here and in the plain of Cadderly, where they could also

fish; and here, if we turn to the right, and just before going into

the bay at Cadderly we come to a little island called Eilean

Uisneachan, and on that we must certainly land. It is only a rocky

spot with a bush or two on it. It was mentioned that the Uisneachs,

when hunting, put up booths, which attracted the attention of at

least the narrators in the legend, by having three apartments, one

for sleeping in, one for cooking in, and one for eating in. One

booth is alluded to as having been on an island, and the name of the

island remains. A chart lately published gives Uiseagan, but this is

evidently wrong, as we may judge from the Old Statistical report, as

well as present inhabitants of the district. The latter would mean

the Island of Larks, a name most inappropriate, we may say absurd,

since it is only a rather flat rock covered with smaller stones, and

a few reeds and briers, certainly not for larks. There was a pile of

stones of considerable length, but so irregular that it was not

certain that it was a heap caused by the fall of any structure,

although it was about the length of a couple of cowhouses of a size

common enough. Passages were made through the heap, and a rough long

hollow was reached, such as might be made when mere boulders are

used for building; but the chief indications of residence were

pieces of wood which had been cut into pegs, and various pieces of

charcoal and bones. It was such a ruin as might come from "the

booths of chase" divided into three. But a still better proof of

continued or frequent habitation was outside the island, there being

the distinct ruins of a road out of it, and on to the land,--a line

of stones evidently was made leading to a good landing. It is easy

still to see some of them out of the water; they are not entirely

dry, I believe, at any time of the tide, but they were intended to

support a dry walk to all appearance. The island is scarcely a

hundred feet in any direction, a mere lake-dwelling, a place

protected by the water on all sides, but only partially at this

entrance.

And so we may look

around in this arm of the sea as if in an inland lake, where only a

wild Highlander in old times could go, a place still frequented by

seals and cormorants, eagles and foxes; although in summer visited

by screw-steamers, it is probably quieter now, and less inhabited

than ever it was, even from the first century, or how much longer no

one can guess. I have come up here in a mist when the sky seemed to

come down and shut us up as with a lid, so that we saw only some

fifty or sixty feet up the hills, and to those from the sunnier

south it produced fear and a desire to escape never to return.

Loudoun.—Now

that these numerous reminiscences of Uisnach have left us a probable

interval, I will take you across to another spot; it is Inver

Liebhan on our left hand, a pretty bay at the mouth of a stream,

where, too, is a farm-house and a piece of ground not difficult to

climb. I came here thinking to sec a great cromlech. We find an

enormous stone; but we must first walk up among the trees, which are

neither many nor high, although a great ornament to the glen.

It is easy to see

that this is no cromlech, or dolmen, or anything but a great fallen

rock, which has lighted on three small stones, which for size are

somewhat in the proportion of castors to a table; it may be that the

rock was lying on the soil, which gradually was washed away, leaving

these stones only. It is a geological lusus, and many a dreadful

fall takes place on these hills capable of explaining such. On the

other side of the hill, namely, on the Awe, a boulder was found on

the middle of the road, settling one morning just before the coach,

so that no vehicle could pass; and on the southerly side of the same

river boulders and gravel seem to be rolling all the year,

attempting to fill up the stream, which is white with the struggle

against them.

O'Keefe.—Now I

am tired. There is a want of stories here; you ought to know more

about the place. Land me on the North, and I will walk to the

quarries and see some activity.

Cameron.—If

you stop at the point before the quarries I will show you another

Uisnach memorial. We shall be there as soon as you.

Loudoun.—What

is that called?

Cameron.—We call it

Ruadh nan Draighean, which would be Thorn Point; but some prefer to

write it Druidhean, which would be the Druid Point. I confess that

the Druids and the thorns have a struggle here, and perhaps in other

places. I see no thorns, and the rocks are too protuberant for us to

suppose thorns to have abounded.

The remains are

apparently those of irregular bothies ; some naturally placed stones

have been doing duty in a cottage; some of the lines of wall are

curved, others straight. These have been dwellings, but we can

scarcely now say how rude; we know that stones may somewhat change

their places where soil and vegetation and heavy rains are, not to

speak of the inclination of the hilly ground. A tradition has been

mentioned that a daughter of the King of Ulster came to live here,

having run away with a son of the Earl of Ardchattan. Now, I suppose

there has never been an Earl of Ardchattan, but that is of little

consequence. A lady having run away from the King of Ulster and come

to this place may fairly be looked on as a part of the tradition,

and a very old one it is, and, when coupled with the names of places

already mentioned in our conversations, remarkable enough, and

reminding us to the last of that Uisnach clan, which has been so

long neglected although it first made the place famous.

Loudoun.—Now,

Mr.O'Keefe, since you have arrived, spend a moment in looking at the

small remains of a dwelling of one of your country's heroines. As to

us, we shall move about among these rocky shores and look for seals,

and give you time to examine the quarries, which we can see well

enough for our wants from the shore. We shall then take you in, and

move onwards.

Cameron.—We

have quite time to row to Ruadh na charn, opposite Ardchattan

priory, and then on to meet the coach for Oban. The men are not too

tired, and they do not require to go farther back than Bunawe.

There is a ferry at

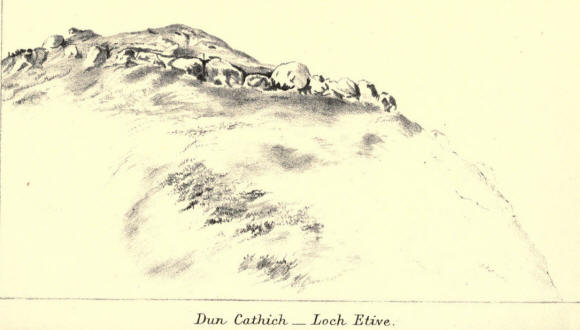

this "cairn point." Whether the word refers to the stone circle on

the conical hill itself I do not know. The hill is said to be 169

feet high; it is called Dun Cathich, probably the hill of battle,

and the large stone circle may be a burying place as smaller ones

are, although the encircling of the top has led people to call it

rather a Dun. The stones are large boulders of the Durinish granite,

carried over, I suppose, although not arranged by glaciers. They

touch each other. It is not a common style of fort, and a drawing

has been taken. (See Fig.)

It is said to have

been used as one of a chain of beacons, and this may be. There is

another small hill on the loch, between this and Connel, called Tom

na h-aire, the mound of watching, which evidently marks the

habit.

Loudoun.—And

here we arrive at the Abbot's Isle again, the monks' small kind of

lake-dwelling and place of refuge, whilst we run in by Kilmaronaig.

We have passed along

the shores of Loch Etive, and have seen the glen; we must leave

others to climb the hills to seek the Pass of Terror, and tell us of

the dwellings of the deer, and the summits where the eagles mount.

We shall require a lodge in the mountains before we can reach these

tops, and must have no daily interruption by descending.

Margaet.—We

have seen the principal haunts of the sons of Uisnach, and now I

should like to know who these Celts were and how they differed and

do differ from other people.

Loudoun.—We

may reserve this for a quiet conversation at Oban. |