|

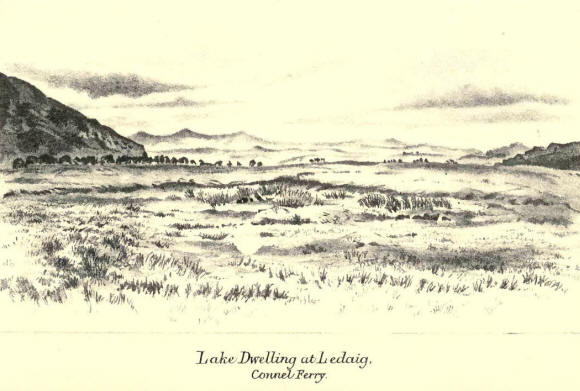

Ian.—This time I

think it would be better to walk over the moss and learn to jump

over the wet places: it is a weary thing to wander along a straight

smooth road, but on a moss we leap from tuft to tuft, and it keeps

up our spirits and gives us a springy step.

Margaet.—And

wet feet. I must dance like a young girl to get along; you are much

older, but you Highlanders keep up your vitality.

Ian.—Of

course; by walking over mosses. Well, I will show you something

wonderful. I will lift that grass and dig black peat from below, and

near the peat I will show a wooden foundation. We shall see ashes

and bones, with proof enough that these wild looking places were not

wildernesses in all times.

That hollow is a

watercourse for a small stream: it once held a greater supply, but

the water was sent down the other way, namely by Achnacree, about a

hundred and twenty years ago. You see that where the water flows

most rapidly there is green grass ; where it is most stagnant there

is moss, and where there is little or no water there is heather.

Margaet.—But

that is quite flat. Surely it never contained a stream.

Ian.—The broad

flat part was a little lake from which the stream flowed, and the

name was and is Loch-an-Tawail by sound, which may be Loch-an-t'Samhuil

or Loch-an-t'Shomhairle, the Loch of Samuel or the Loch of Somerled.

It is sometimes flooded now, and was more so when I was a boy, and I

used to wade into that green place in the middle, which now is

difficult to distinguish from the rest.

Sheena.—Yes,

yes; it is all nothing. Willie and I walked over it and there are

only a few holes and a few stones. Like so many things we come to

see, they are all gone before we come. I expect the hills soon to

disappear; indeed I should not be surprised if they are gone when we

waken to-morrow, these antiquities produce so many illusions.

Cameron.-If a

mist comes over the hills or over your eyes you will not see much,

and a thick mist of peat covers that which you will see here. The

best part is not on the surface. In this hole, into which you looked

carelessly, are seen beams or rather young birch trunks lying

horizontally heaped over each other like pig-iron. This extends to

the bottom. I am not sure of the deepest, but some are about five

layers deep, perhaps usually four, and others may be more. There is

a nearly oval figure formed by a slight raising of the turf, and in

the middle is a still higher part. This oval is about 50 feet long

and 28 broad; it evidently marks the dwelling, but the tree

foundation goes beyond this to the breadth of 6o feet. And now I

will leave you to ask questions, or to read a description which I

have taken out of a book. The book itself is new, as the discovery

was made but lately.

No piles were seen.

There were many leaves, half rotten, and a few branches. The young

trees had been felled with sharp axes ; there was none of the

clumsiness of the stone age. The encircling mounds were but a few

inches high, but they showed organic matter decaying and turned into

peat. It seemed as if a double wall of wattles had existed, it might

have been peat or grassy turf. I saw no proof of clay to fill up the

chinks: the Highlanders do not object to chinks even now.

The wood was birch.

It is near the "Lake of the birches."

There are few trees

that can give it that name now, but we can imagine a time when there

were many birches. Many scores of the same class must have been laid

under this spot. At the cast end of the oval was an elongation not

surrounded by the turf mound. I believe the foundation extends along

it, and I suppose this to have been a platform before the door, a

place for the inhabitants to sun themselves, and a landing and

disembarking spot. (This platform was afterwards found to extend all

round.)

In the middle nearly,

but a little to the westerly end, of the oval house was the

fire-place. It is higher than the rest of the space. It is here that

the bones were found, with shells and nuts. Under a few inches of a

white powder is the hearth. It consists of four flattish stones;

under the stones is also to be found more peat ash and some few

remnants, but very few, of the substances connected with food. There

were no implements, but we did not look into the most promising

spot. They, if at all, will be found farther from the fire. Under

the ashes is a floor of clay about six inches thick. This is laid as

flat as our wooden floors are.

At the east end, at

an opening or door apparently, to judge from the failure of the

encircling mound, was another smaller and ruder fire-place. The

stones supporting it were found, with abundance of peat ash, bones

and nuts. But the finest fire-place was at the west. The end was

that of an oval, and a large fire-place was at the extremity, with

bushels of ashes. The fire-place was rudely made by a bank of

flattish stones raised above the floor. On each side was a raised

seat, made also of flattish stones, and quite broad enough to serve

for two or even three persons. These seats were the chimney corners

of the chief inhabitants, and fine fires they seem to have had. The

seats might have been covered, and in any case I do not doubt that

they were comfortable. There were then three fire-places in the

length of fifty feet, increasing in importance until the west was

reached.

On the outside of the

enclosure, a large amount of nutshells was found as if thrown over

into the "yard" in a slovenly way.

There is a full

account of lake dwellings in Switzerland by Professor Keller; this

comes nearest to that at WauwyI. There are no piles.

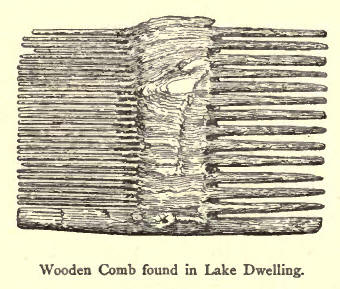

There were found

several wooden pegs, and a piece of a knife not larger than a large

pocket one, a hook such as might have been used to hang a pot,

several pieces of skin soles, and a slipper of thin skin rather

neatly made, not in the Icelandic fashion. There was also the side

of a wooden basin well turned. The wooden articles dried up,

shrivelled, and completely changed their shape in the open air; but

a comb was preserved by being kept in a box filled with peat, which

was allowed to dry slowly for two years. It was made of wood, one

side having smaller teeth than the other.

This dwelling was

larger than single rooms in the Highlands now are. It may, like

Deirdre's, have contained three apartments. The people need not have

been lower in civilization than some we see now, if houses are to be

the criterion. The bones found were split up in the recognised

prehistoric

method. This is

supposed to indicate a scarcity of food : it may also indicate an

idle way of spending time and lounging over the meals, as well as a

liking for marrow, in which we succeed them. When thinking whether

it was possible to judge from this as to the age of the remains, I

asked some friends who had been brought up in the Highlands, whether

any peculiar attention was ever given to the marrow of bones

generally, independent of the admired "marrow bones."

I heard of nothing

like splitting bones among the inhabitants, but it is known in

Iceland even now. A lady from near Loch Broom said that her father

had a peculiar knack by which he could break a bone, and he

occasionally performed it as a feat before his sons and guests,

using a leg of a sheep. The lady did not know if it was done by

strength or by skill, but thinks it required both. Her brothers, who

were strong men, often tried, but could not accomplish it. This is

an evident relic of early times. As many of the prehistoric are also

contemporaneous habits, it would be interesting to trace out that of

bone splitting more fully.

And now as to the age

of this dwelling. The peaty turf over it was soft and full of fibre.

I see no reason for arguing great age from this. Even allowing a

very long term for its growth—a foot in a century—we have only three

hundred years, and, as until 1740 there was a greater supply of

water to it, the growth may have been more rapid. On the other hand,

the stream, in former times, went through here, and it may have

washed off the surface of the moss or prevented the increase. The

trees, however, are quite rotten, and although in every respect

looking fresh, even preserving the perfect appearance of the bark,

the spade goes through them with ease. Birch does not keep well

under water; still, although easily crumbled by the fingers or cut

by the spade when wet, it became actually hard and strong when

dried. It seems as if the water united with the woody fibre, and

made a soft compound or hydrate. This compound was easily decomposed

by driving off the water. It is analogous to the soft gelatinous

hydrate of alumina or iron which becomes hard by drying.

The circumstances are

a little contradictory. The size and independent position of the

house might point to a person of some local village importance: do

the split bones and the poor hearth take us far back, if so how far

? We do not require to go out of this century in Scotland to find

men having only two apartments and still giving judgment as

magistrates or so-called bailies to the neighbourhood for miles, and

keeping the peace better than more learned lawyers have been able to

do. In the Highlands I have myself seen men living in hovels, dark

and inexpressibly low in material civilization, whilst the inmates

had really as much good feeling and general wisdom in their speech

as many men who gave much better dwellings to their cows, and

incomparably better to their horses.

The dwelling does not

show the civilization of the occupant correctly, neither does the

food. In the dwellings mentioned, the food seems to have been far

inferior in variety and elegance to that used in the lake dwellings

of Switzerland among men who are said to have worshipped the water

and the moon.

If the dwelling does

not show the condition in civilization of the individual, neither

does it of the race. We have dwellings from London to Caithness and

Kerry in abundance, as uncomfortable as those of many savages, but

out of some of the worst some of our best minds have emerged.

According to Scott,

many of the Highlanders of the last century were savage, but a

sudden peace brought an almost instant civilization. The talent for

rising was there; where was it prepared? Such a change is not made

among negroes except in rare individuals. The theory of development

forbids us to believe this sudden step to be taken by any nation

never previously affected by civilization. This, I believe, is a

very important point. Such a step proves the organization to have

been previously developed. The organization of a nation cannot be

supposed to develop at once, not even that of an individual. I do

not therefore expect to find savage traits among such people, except

so far as the necessity for struggling produced savage habits, just

as we see that it produces them in war in our own times.

In order to see if a

wild race has a developed organization, it would be needful to bring

up some of the infants to civilized ways. If they showed an

incapacity, we might presume, if the numbers were sufficient for a

good experiment, that they were really savage. If they showed a

capacity, we could not imagine them to be properly savage. The power

may lie dormant, but cannot far precede, we may suppose, its first

exercise. This is said without objecting to the supernatural.

As there is no reason

to suppose that, however inferior as architects, the men were

savage, let us now look for the inhabitants. Who were the people

that cracked nuts at that hearthstone? Did the "mighty Somerled"

live in this lake dwelling?—or perhaps some of the relatives? We are

told that he had possessions both on the mainland and the Western

islands. His power went to the second son, whose descendants are

Macdougalls of Lorn, and live within six miles of this place.

Did not Somerled, who

died in the twelfth century, live in a stone castle? It is most

probable. One of the family may have done otherwise. It is only

certain that he was closely connected with this neighbourhood. We do

not depend wholly on traditions concerning him, as the family and

this Ioch have kept the family name.

A piece of wood with

a cross burnt on it caused a good deal of interest. This kind of

cross is not uncommon in the old Irish remains. It is a Greek cross

with crosslets, and has been imagined to indicate a time before the

Latin Church entered. It is, however, an old form also in Iceland,

which greatly weakens all this speculation, already shown by Dr.

Stuart to be incorrect. Indeed, we may see almost exactly the same

forms in his great work, "The Sculptured Stones of Scotland."

As the present

Icelandic forms are identical with the cross found, so may the

purpose be; but we know that religious forms sometimes degenerate

into such things as witchcraft and charms. Mr. HjaItalin tells me

that they make in Iceland exactly the same cross, but without the

circle, on a piece of paper, as a charm when going to wrestle. It is

put in the shoe with these words:

"Ginfaxi under the

toe,

Gependi under the heel,

Help me the Devil,

For I am in a strait."

These words at the

beginning may be very old, the meaning not being clear I am told.

Mr. Hjaltalin also refers to "Travels, by Umbra," for several

varieties of crosses like these. [A cross with different lines upon

it is given by Jon Arnason in his "Islenskar bjodsogur og Aefintyri,"

vol. I., p. 446, and Ginjaxi under it. The charm is given a little

different on p. 452.]

It may be repeated

that I do not consider the lake-dwelling to be very old. |