|

Cameron.—I wish

to take a walk round the moss, and we may begin at the ferry. There

is a little mound here called the yellow mound of Connel; it may be

old, and it may contain something interesting.

Loudoun.—Here

at least is something certainly old, the deeply cut bed of the river

below. It must have taken long to cut through that rock.

Cameron.—Can

water do such a thing?

Loudoun.—Water

may do it in time, or in the ages that look to us like eternity, but

we do not rely on it wholly. It brings down stones from the hills

and they grind rapidly. It is rock against rock, and you know sand

or small stones are now used as a means of boring and of polishing.

Willie.—At any

rate it has left the banks capital for rabbits, and these gipsies

live here and probably feed to a great extent upon them.

Cameron.—Yes,

these are Ceardan, or, as we should say, tinkers. In Scotland they

are not called gipsies often. I suppose that before the gipsies came

the tinkers went about much as they do now, doing metal work for the

people. They can make, or at least they could make, silver brooches

with very simple tools, and we know that in other countries, in

Persia, for example, there are similar wanderers, but far more

skilful, who make those beautiful and elaborate bronze vessels of

open lacework with figures numerous, fantastic, and mythical, some

indicating serpent-worship, ideas received probably from

neighbouring states or Indian nagas. I mean that either the art, or

the idea, or both, came from elsewhere.

Margaet.—Can

it be that these men live out of doors with no covering but a slight

tent, and some with only a covering for the head? These women, too,

seem no more robust than ourselves, and they are poorly clothed. How

can they live?

Loudoun.—By

ceasing to think, it would appear that a good deal of the vigour

goes into the body, and these people are very idle in body and mind.

Margaet.—But I

thought that exercise kept us warm, and if these people were idle

they would starve.

Loudoun.—Exercise

does make us warm, but great exercise needs rest, and we must be

strong indeed if we do not cool too far after it. I think it

probable that these people, not being of the strongest, would need

more shelter if they were very active. They would convert into

energy that which they now have in warmth, and lose much heat also

in evaporation. They do not usually stand the winter well, they go

into towns as a rule; but there are some who keep out, and it is

only lately that one died in a tent on the snow near Forres, the

rest of the tribe lying around him. He had never since youth lived

under a roof.

Margaet.—But

surely vigorous men can stand cold best.

Loudoun.—Certainly;

but cold brings down even their activity, and if very much exposed

they cease to be powerful. I don't like these people ; they are lazy

and beggarly whether real gipsies or not.

Cameron.—This

is a great moss at our left. And the road seems to be on an

embankment around it. Cairns are on the roadside as if the moss were

very old. This cairn at LocIianabeich has a large base, indeed only

the base remains, as the barns were built out of it. There is

nothing in it above the original surface, but no one has gone lower

and it may conceal something interesting. Some people say it was

only a collection of stones to clear the land, and there is some

land cleared here for the farm.

O'Keefe.—Here

to the right is another collection of stones; do you think people

would put them in such a picturesque place if they were only

collected from the road? These look down on the loch and ornament

the fine bank.

Cameron.—Yes,

it is a fine bank, a bank of whin and gorse, and lively with rabbits

black and white. Who would have thought a few years ago that the

telegraph poles would have run along the top and the wires crossed

the loch, and that a dyer would be building works opposite, and the

school board interfering with the lonely shore.

We progress, as you

from the South say, but I do not like the people better. I like the

old people in these cottages, with their little crofts behind, and I

know they enjoy walking out in that wood and round the great curve

of the road which opens up the wide part of the loch and shows us

Ardchattan, the churches and the priory, as well as the great hills

and the openings into their dark recesses.

Down there is a piece

of an old ruin near the sea-shore. I do not know what it was, but it

is near the houses of decent men whom I know, and I admire the view

on which they feed daily when standing at their own doors and

looking up to Ardchattan over the broad part of Loch Etive. Those

who do not fear running down the hill may run and look, those who

prefer to keep to our principal object will walk along. Here we come

to the peat moss out of which we got the spear head. We shall follow

the road as it leads round the great bend of the loch, widening like

a sea, and turn round to the left until we come to the clump of

trees and the great cairn.

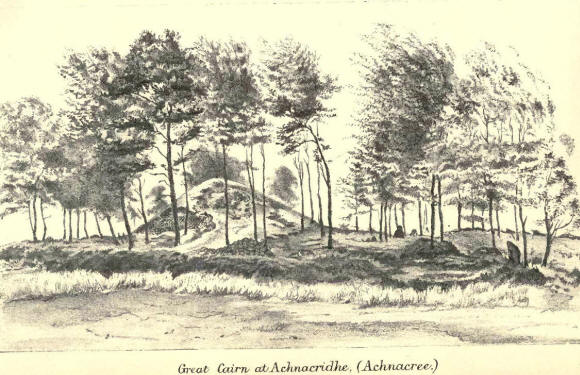

Sheena.—I

think I must be showwornan here as I took so much interest in this

cairn. You perceive that the enclosure is great although the traces

of the ditch are small, and of the large stone circle around it

there remain only some fragments. The height appeared greater before

opening, although there was only a little taken off—the change is

more observable in the shape. If you go to the top you see a wide

opening. The stones taken out were thrown to the side, and the

original appearance is best understood from the drawing. It took two

men eight or nine days to make that opening. The plan was to go down

from the top, but as the stones were continually rolling in, it was

quite necessary to make a broad opening above, and in order not to

diminish the height, if possible, we kept a little to the west side.

After sinking about eight feet we came to a flat stone which broke

readily in pieces—some of the slate of the country. This really had

an Aladdin's cave appearance, and we were all anxiety.

We had come to the

extreme edge of a number of flat granite stones, which were found

afterwards to form a roof. At the side, and under the granite roof,

was the opening which had been filled up with slatey material, and

it was this opening which served for all the exploration.

Fortunately we had struck upon the spot which, of all others, was

most suitable for entering without destruction of material, since

the avenue forming the true original entrance was found to have

collapsed, and had we seen it at first we might have been tempted to

remove the stones from their position in order to make way, thus

destroying the form to a considerable extent. And now every stone of

the building is exactly as we found it.

It was a weird thing

entering that cairn that had been so long closed, and it was a

cheerful thing to come out and see the people that had gathered,

even from this lone district, as soon as they heard that there was

really a building and chambers found in the cairn. It was curious,

also, to listen to the superstitions that came out. One woman who

lived here, and might therefore be considered an authority, said

that she used to see lights upon it in the dark nights. That you may

explain as you please; distances are not easily judged of in the

dark. One man, who also lived near, and who certainly was

intelligent, said he would not enter for the whole estate of

Lochnell.

We have often

inquired the name of the cairn.

The cairn really has

had no definite name. Some people have called it Carn Ban or White

Cairn, but that is evidently confusing it with the other cairn which

we saw over the moss, and which is really whiter. Some people have

called it Ossian's Cairn, but that is not an old name, and even if

it had been, we know that it is a common thing to attach this name

to anything old. We call it Achnacree Cairn, from the name of the

farm on which it stands. It was a pleasant day for us and all around

to find an interest so human and natural arising out of things deep

in the ground in this secluded place, and it makes one wonder

whether there be not, in every part of the world, something that

might interest us all if we only knew how to look at it. But I shall

not describe the structure of this cairn, leaving you rather to read

what has already been said on the subject, which is as follows:—

DESCRIPTION OF THE

CAIRN OF ACHNACREE.

It was desired not to

disturb the actual top, so as to diminish the height, but it is to

be feared that the care has not been sufficient. After the men had

worked for seven days, a granite slab was found sixteen inches

thick. After three more days the boulders of the cairn were taken

down in quantity sufficient to render the slope safe enough to allow

of an entrance. The great danger in these cases comes from the

rolling of stones easily moved by a touch, and falling down to the

bottom, so that they require to be lifted up at least as high as the

side entrance. The intended entrance was then sought for. Two stones

that seemed to us to have been portions of a stone circle round the

cairn, now showed themselves rather as gateposts, since the chamber

seemed to point in that direction. An opening was therefore made

between them, and a narrow passage found. This passage was made of

brittle slate pieces of about three feet in height, and, in many

instances, less than a foot broad, forming the sides, and covering

the way. These were not in good order, the weight of the cairn had

evidently caused a tendency to collapse. The way was also nearly

filled up with stones, put there with intention to make the entrance

difficult, as it would seem. When working at this narrow entrance,

an old man from the neighbourhood, who had been engaged to assist

the others, said that he had found an opening there forty years ago,

when removing stones for building. When General Campbell, who was

then proprietor, saw this, he prevented further disturbance. There

was no entrance made, but the opinion continued that the cairn was

hollow. Evidently no one had entered it at that time. There was a

story of some bones having been found, but I do not know at what

spot; probably in a cist outside the cairn.

The apparent

dimensions of the cairn were 15 feet in diameter, and 15 feet high.

It is now somewhat lower. If the pillar stones at the entrance made

a continuous circle at the same distance from the centre, the

diameter would be less; at present the boulders of the cairn pass

even that limit. Possibly an outer circle was meant to support the

sides of the cairn, but I incline to think not. Many of the stones

have been removed on the side, so that one might doubt the shape of

the original; but I think, from the remaining part, that the whole

was one great circle. On the side farthest from the road is a ditch,

forming part of an outer ring of 135 feet in diameter. On the edge

of that, again, there are some stones which appeared, when I first

saw them, to be the remains of a stone cist rudely built, but so

much displaced by the growth of trees, and other still later

accidents which have entirely broken a part within a year, that it

is not now easy to distinguish the form. We must consider, then, an

enclosure about 400 feet in circumference, and within it, probably a

dozen feet from it, a circle of standing stones. Of this I can find

only one stone remaining ; but it is so like a standing stone for

the purpose, that it seems to have no other duty. I received this

idea from those circles round the cairns at Clava, for example. An

embankment is not uncommon ; one is seen on a gigantic scale at the

Giant's Ring, near Belfast, where several acres are enclosed by a

high earth wall; in the centre of the circle is a cromlech, with two

covering stones, like one of those described at Ach-na-Cree-beag;

one has fallen down on one side. Some of the supporting stones have

been removed.

We must suppose the

cairn itself to have been at first much smoother and more regular

than now, even if not supported all round by a wall of standing

stones, like those now forming the entrance.

Before entering the

cairn, I had the pleasure of a visit from the Rev. R. J. Mapleton of

Duntroon, who kindly came with his great experience. This relieved

me, as I was then inexperienced and was unwilling to venture on

touching ancient monuments, and I began with the full hope of

finding help. Mr. Mapleton has aided me in the description.

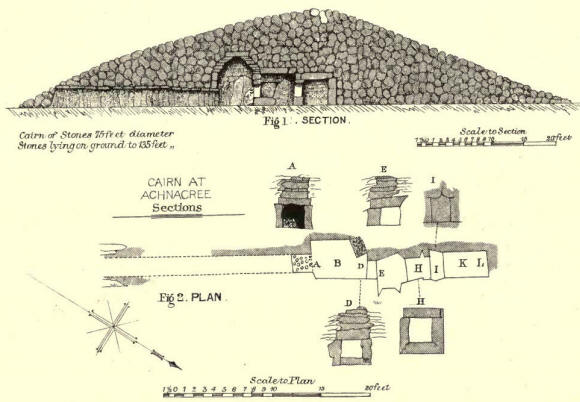

Fig. I, Plate showing

the sections, gives the size and height according to the measurement

of Mr. Ritchie Rogers, who kindly undertook to survey the whole,

both within and without. From him the originals of the drawings of

this cairn have been obtained on a scale, and they are now enlarged

to be shown.

The inner circle

shown on the diagram is that of the cairn itself. The dotted line is

the original passage, now a good deal obstructed with loose stones,

and not passable. The outer circle is that of the fosse. A supposed

third circle would be between these two.

A (Fig. 2) is the

entrance, as seen from the chamber B, C chamber not marked. The

point A is to the S.S.E., and may be called the southern point. In

reality, however, we entered at, L, where a few of the loose stones

at the top of the wall were removed. It was needful to go feet

foremost, and to allow ourselves to drop gently to the floor.

In the diagram shown

at the Society's meeting, there was also a view of the side walls of

the chamber and passages on the east and west.

Fig. 2 gives plan and

elevation of passages. Going from L we first meet passage I next to

H, then E and D, with the stones of the wall over them always

becoming smaller. We then come to A, where the proper entrance is;

the plans of the openings are placed in the plate opposite to their

positions.

In a corner of

chamber B is a large boulder, probably put there from its having

been ready at hand; at present it forms a part of the wall, although

by jutting out it becomes an irregularity.

Having then entered

feet foremost at L, the first thing that struck the eye was a row of

quartz pebbles, larger than a walnut; these were arranged on the

ledge of the lower granite block of the east side, with two on the

west. When we looked into the dark chamber from the outside they

shone as if illuminated, showing how clean they had remained. They

are rounded and not broken. The total length of the chambers is

nearly 20 feet, not including the long passage, and it may be said

to be tripartite, although the centre part might be held to be

merely a passage. The southern part, B, was intended to be entered

first, and is the largest, 6 feet long and 4 wide, the height 7

feet, but diminished by an accumulation of 8 or 10 inches of soil.

The entrance at A was capped by a large and roundish block of

granite resting on two slabs, and leaving the doorway to be only 2

feet 2 inches high and the same wide. On the stones forming the

passage no markings could be expected; they were rough and brittle

and slatey; no markings could be seen even on the granite, although

there were places convenient enough for the purpose. The walls were

formed of two blocks or rather slabs of stone, supplemented only by

a rough walling, as seen in fig. 4. The slabs are placed on edge and

lying end to end. On both sides where two large stones met was a

kind of triangular space filled in with loose open walling, so that

the hand could be inserted between the stones. On thrusting the hand

in, the place around seemed to be so open that Mr. Mapleton was

inclined to think that a recess might be behind. The roof was very

interesting; the stones of the rough walling rose from the rocks

below, and gradually approached each other, until the space was only

3 feet 4 inches by r foot io inches. This was covered over by one

stone, as depicted. The chamber was therefore roughly domed, in this

respect resembling many buildings of later times. The soil was loose

to the depth of io inches, chiefly fine gravel, with some larger

pebbles. When Mr. Mapleton lifted it up with a small trowel it was

passed through the fingers; after bringing it to the light, many

dark specks were found, appearing at first to be charcoal, but on

examination they were found very soft, and might have been from

decaying vegetable matter. It rained whilst we were in the cairn,

and heavy drops came down into the domed room where the centre slab

did not cover.

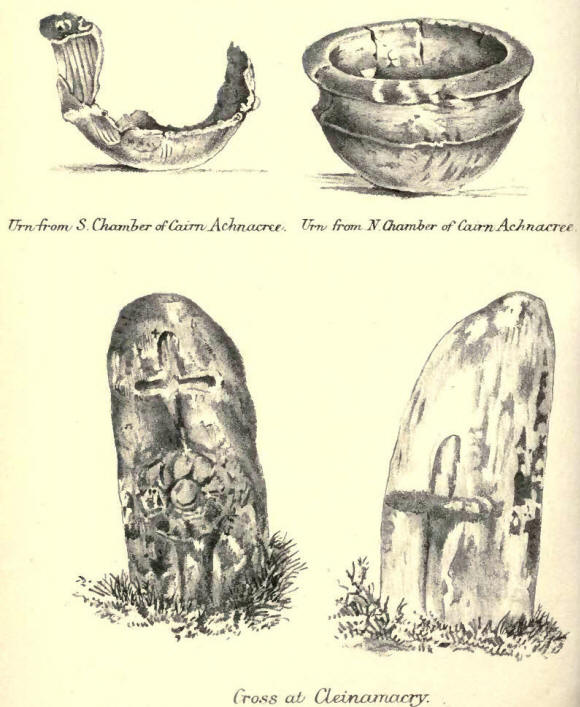

There was nothing

found indicating a burial except the urns ; in the large chamber was

one, or rather part of one. There was no instrument of stone or of

metal. We dug down to the natural surface, or some inches lower.

However, the urn was not below the natural surface, but on it, and

under the looser soil, lying on its side close to the mid part of

the eastern wall. The position seems to have been its original one,

the parts missing have probably decayed from being less completely

burnt. The loose parts came out as if from their proper places,

although detached. Another explanation is possible. The form is seen

at Fig. I, small neatly raised portions forming incipient handles.

The urn is round below, and consequently could not stand by itself.

Earth and stones were the only contents. A pebble of the same size

and quality as the white ones mentioned was inside, and had become

brown like the earth around.

The markings on the urn have a neat appearance, although done by

simply drawing a point down the side. See Plate as before, Fig. I.

The exit from this

chamber leading to the middle compartment has two large slabs,

supporting the roof or cover on the cast side, resting on a wall of

small stones, and on the west are the more solid blocks. The walling

ran half way across the passage, which became narrowed to about 2

feet. This doorway E was filled up with stones built firmly in after

the chamber had been completed, and not supporting the structure.

They had no appearance of having been placed there recently,

although they were lighter in colour than those forming the upper

part of the wall. Those in the passage had the same light colour,

and were still of the original building. I understand that the

apparently premeditated filling up of a passage is not uncommon.

The middle part H,

which may be only a passage itself, is 6 feet 6 inches long, and 2

feet 4 inches wide at the south end, and 2 feet 1 inch at the north.

It is 5 feet 4 inches high. Both sides were very similar, each

formed of two blocks, and above them 3 feet of firm dry walling. A

stone was found lying across the compartment nearly hidden in the

loose soil. This gave the idea of sub-compartments, such as had been

found by Mr. Mapleton at Kilmartin, but on examination it was seen

to have been placed there only for strength, being large and

irregular, and occupying a great part of the floor, although well

fitted for keeping the sides from approaching.

The floor of the

whole was strewed disorderly with boulder stones, but this I

understand is common ; to me it suggested entrance and robbing,

whilst some careful hand closed all up. This, however, must have

itself been early. The cover of this middle compartment was a large

slab, the edges of which could not be seen.

The doorway, I, into

the north division, is 2 feet 9 inches. A long stone lay across,

perhaps to tie the two sides, perhaps to support the ends of the

covering slabs, or both. We suppose there were two slabs to this and

the middle division, but we could not see the junction. This north

compartment is 4 feet 6 inches long, 3 feet wide, and 4 feet 8

inches high, if we do not remove the loose soil, otherwise 5 feet 5

inches. This north end is formed by a slab, supplemented as

elsewhere by rough walling. The east side was formed of two long

slabs set on edge, the upper one resting on the lower. The space

above has rough walling 1 foot 6 inches high. The west side was

similar, except that the upper slab rather bent down and left a

wider ledge. The lower slab was 1 foot 4 inches thick, and 1 foot 9

inches high.

About the middle of

the ledge, on the cast side, were placed six white pebbles of

quartz—four in one part and two a little separate. On the west side

were two white pebbles ; others of the same kind, but discoloured,

were found in the soil. Three pebbles were found in the urn on the

east side, and one in the others, so far as the broken state allowed

us to judge. One urn nearly entire was found on the west side, and

above the ground on the east side were fragments of two which

appeared to have crumbled to decay, although the appearance could be

explained by their having been broken and parts removed. We may ask,

why should people have removed portions? The most complete was found

exactly below the greatest number of quartz stones.

Fig. 2 shows the best

preserved urn; it accompanied the fragments of two others. All of

them had been quite round below, and they had no feet; this is true

of two of those in the north certainly, and of the one in the south.

Those in the north had no handles, not even incipient.

There was no injury

done to any part of the structure, unless we except a crack in the

tie-stone between the north chamber and the passage. This crack was

old, and seems to have been the result of weight only.

The quartz pebbles

have been often noticed. Mr. Mapleton has found them often in urns

and cists in this county, and in one case near Lochnell and far from

quartz rock. He thinks they are generally associated with cows'

teeth. He found three angular pieces of quartz firmly imbedded in a

deep cup made in the rock, and surrounded by rings or circle

markings, in the Kilmartin district lately. These markings were

covered over with about 15 inches of soil, in which no quartz

occurred. Dr. Wilson mentions twenty-five urns having been found on

the Cathkin hills, each with its face downwards, and a quartz stone

under it. Mr. Mapleton inclines to dwell on the idea that the quartz

pebbles were symbols of acquittal, according to the custom of the

Greeks of using white stones, shells, or beans, and refers to the

second chapter and 17th verse of "Revelation." There certainly we

have the word used, psephos, a pebble, from which psephizomai, I

vote, is taken; votes were put into urns, or in Rome into kists. In

Egypt stone tablets were put with the dead, but these were written

on. We know that the Egyptians measured out the good deeds of the

person who died. These ideas are interesting to keep in mind, but do

not bring absolute proof. We might, indeed, say that quartz pebbles,

from their remarkable whiteness, were selected as ornaments out of

the brown material generally forming the rocks or soil. Children are

very fond of collecting them, and most families at the sea-shore

have some. They are even seen in rows on window sills, and along

garden walks and at rockeries. The same idea of beauty might take

hold of the national mind of an early age; this would explain to us

why the peebles are found in so many positions, whether in Asia or

with us. They are known to form smaller circles within the large

stone circles and elsewhere. Still this does not contradict the idea

of their being symbols, it may even assist it.

It is not easy to

tell the age of this cairn—some will say the Neolithic, but we have

found no instruments or manufactured articles besides the urns to

prove it, and their forms are not conclusive. The lack of metal

leads us to think of iron which is readily rusted. Still we found

the spear-head at the bottom of the peat over there, and it was good

bronze, and you may imagine the warrior who used it to be buried in

this great memorial, for it was great, and its surrounding ditch and

rings made it ornamental. Bronze was used at a very late age in

Celtland of the north, and old habits would keep with it. Burial

also in chambers allowing of a sitting posture was used up to the

twelfth century among the Scandinavians. However, I know no such

cairns of that age in this country. We read in "Burnt Njal" of one,

a chambered tomb having, for honour, been given to the fine hero

Gunnar; but had this been of his age, arms would certainly have been

found here.

Sheena.—But

there were urns. The people must have been burnt.

Loudoun.—No.

The vessels may have been drinking vessels; no body was found, and

it is fair to argue that high and chambered tombs could not have

been intended merely for urns, and it is probable that they were

meant for bodies in the sitting posture originally, although used

afterwards for the lying posture. The proper, and probably original

receptacle of the urn of burnt ashes is a stone kist later it

descended to be a niche only. [See "Notes on the Survival of Pagan

Customs," by Joseph Anderson, Esq., Proc. Soc. of Antiq. of

Scotland, vol. XI., part ii., p. 363. 1876.] |