|

"Do gluaisedar rompa go

daingen Mhac n' Uisneach acas go Loch n' Eitche an Albain."

"They went to the fort of the sons of Uisnach, which is at Loch

Etive in Alban."

Loudoun.—I

think I shall stand on the fort, and give you quite a lecture on the

subject. It may be dry, but it will serve for conversation

afterwards.

I have ventured to

adopt, or at least to hold provisionally, the opinion that the

vitrified fort of Dun Mac Uisneachan was inhabited in the early

centuries of our era. We need not be desirous to define particularly

the date to a century or two. Traditions and the dawnings of

history, like the fancies of childhood, are mixtures of the real and

the ideal, whilst time and place are not very distinctly bounded.

All fancies about

earthquakes, volcanoes, and lightning, go also from the site—fancies

which I would not mention had they not been entertained by men whose

opinions are to be respected on other subjects.

The hill on which is

the Fort is long in proportion to its breadth. The top is pretty

well defined, as the sides are almost everywhere either very steep

or actually precipitous. The length is from 250 to 300 yards,

according to the point of starting; its breadth at the most 5o. The

broader part is near the west, and looks on the Bay of Ardnamuic,

with a magnificent view around. This part is most fitted for

habitation, and has been most inhabited; it is also farther from the

side where the rise is more gradual and an attack easier. Here about

the highest part were the houses built, or at least the more

important, and here were the meals, as sufficient remains show. On

the north of this part are natural walls, One may say, as well as on

the south, and between these, well defended from the storms, the

principal dwellings were built. On the west there is a space of

nearly 40 yards before reaching the precipice that formed the

boundary on the shore. The central living place, was 30 yards broad

by about 45 long.

The debris was not

rich, except in bones of common animals; but here were found the

iron brooch which I shall show, also the mica and bronze wire. The

mound on the land side seemed to be natural, and only an accident

led me to doubt this. It was found to be the remains of a strong

wall regularly built, and defending the inner part of the fort even

after the rest of the enclosure, or top of the hill to the east,

might be taken. About 6 feet high of the debris still remains, but

it slopes down gradually, and is covered with grass. The inside was

not so high as the outside of the wall. There was an inner wall,

apparently more carefully built than the outer, and more fitted for

a house than a fort. This inner wall followed the slope of the

ground, and did not form rectangular apartments. The enclosure,

however, is not all dug up. There was an entrance to it from the

western court, as we may call it, through a narrow passage.

Vitrified walls are

found along the outer edge of the hill in most places, and on the

western part an inner wall runs along them, the breadth and space

between being about 9 feet. The vitrifaction is never carried

inside, where a more refined work was required. The vitrified wall

is not built on absolute precipices, but on those parts less

difficult to scale. The cross walls, even those defending the

central or high enclosure from the camp, are not vitrified.

At a point of the

northern wall there was dug up a piece of enamelled bronze, 13 inch

in diameter. It seems to have served as a cap or cover, as there is

a hollow on one side into which something may have fitted. On the

other are concentric circles, the hollows being filled with enamel,

and that of a red colour, whilst the centre piece is of a slight

yellow. It belongs to the class called champleve.. Ornaments

of concentric circles are by no means uncommon in the drawings of

Stockholm bronze objects by Professor Montelius of Stockholm, and

there are many in Mycenae, but the enamel points rather to Celtic

art, without determining the century. I should be glad to have some

indication of the origin. Concentric circles are ornaments on many

works of art; they are found on the ancient sculptures of this and

neighbouring countries, as well as on the remains in Schliemann's

Trojan Collection. Schliemann gives figures of them in his volume,

p. 137, and on plate xlvii., English edition, where also circles of

depressions are seen, although on a small scale, not unlike northern

cups and circles as on p. 235. The red oxide of copper gives the

colour to the circles on the ornament found here. The yellow central

piece is very like that used a good deal by the Japanese, and said

to contain silver. This centre piece is so small that I am unwilling

to destroy any for examination ; besides, it is entire, whilst the

enamel of the circles round it has come out to a large extent.

These points are made

out:-

(1.) The weaker parts

of the dun were walled, the outer wall, or part of wall, being

vitrified.

(2.) The wall of the

western part is double; the outer being vitrified, the inner built

in layers of flat stone, 9 feet being the distance from surface to

surface.

(3.) The interior

walls were built without mortar, whether they were cross walls or

formed a lining to the outer wall.

(4.) The eastern wall

of the inhabited part had been rebuilt in a ruder way, partly at

least, by using some of the waste of a vitrified but broken down

portion.

(5.) The occupation

was continued after the ruin of the chief structure, perhaps by

stragglers, or as poorer cottages now linger about ruins.

(6.) The occupants of

a vitrified fort were not necessarily the builders. This fort may

have been built for the Uisnachs, and as more than one of this kind

is connected with their name, this may possibly be a style which

they preferred, although they had other dwellings not vitrified.

(7.) Vitrified forts

are not common in Ireland, and the improbability of the Uisnachs

bringing the plan or custom over is great; indeed, we may say that

they certainly did not. It is probable that the forts were built for

them by the people of Alba, and that this was the fashionable mode

of building at the time for important persons. I am not inclined to

see anything mythical in the name when more than one is called after

Deirdre. The word myth is not a very definite one as used by

antiquarians, and often denotes merely a fact which has lost its

original clearness.

(8.) The vitrified

fort was introduced by men who quite understood the mode of putting

dry stones together in layers. A part, of the vitrified mass in situ

was overlying a built portion of a wall.

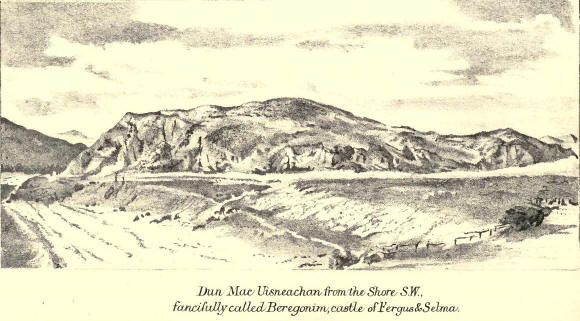

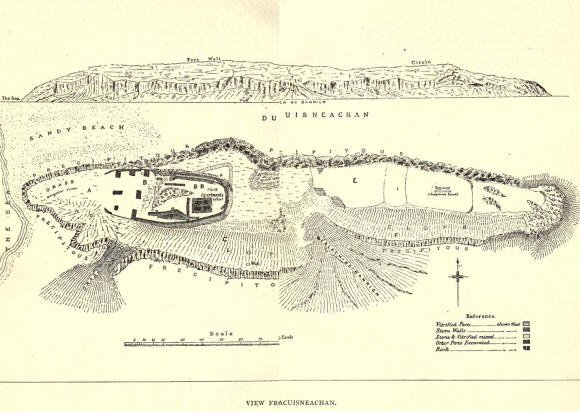

Here is a plan of the

surface, and a drawing from a photograph of the isolated hill

itself.

The surface is so

unequal that I cannot give a good idea of it without a number of

contour lines and such care in survey, that I do not think I can

give it that time or attention necessary, even if I were accustomed

to that class of work; probably enough will be shown on the Ordnance

Survey map, which is not yet published.

Vitrified walls take

us far back, but not necessarily beyond the early centuries of the

Christian era, since one existing near St. Brieuc, in Brittany, was

evidently built after the Romans had shown their skill there. To the

earliest possible date we have no clue further than this, that it

would appear as if it were when both iron and bronze were used. Of

the latest date we have a probable negative indication. Such forts

would cease to be built when the country was laid bare of wood, and

that certainly would be after the Roman occupation of the east of

Scotland; in the west the habit would last longer. It is probable

that they would cease in the east of Scotland before the west,

because new ideas came there to break up the life of the earlier

times; the habits in the west remained longer allied to those of

Ireland. The forts themselves were a fashion brought from the east

of Scotland to the west. The later influx of people from the west,

or Ireland, was accompanied by no such mode of building, although

previously the east, perhaps by way of the north, had inoculated the

Western Highlands with the habit, and slightly touched the opposite

coast of Ireland.

The vitrified forts

are the work of a rude people learning to emerge from the ruder

state indicated by building loose stone walls, if we may judge from

this of the Usnachs [I purposely spell the name a little differently

here, so that it may be seen that there are various methods.] When I

say the work of a rude people, men without much external

civilization are meant. I have continued to disconnect more and

more, as already said, the style of the dwelling and the character

of the inmate, except in some particulars, and one of these is that

there is often not energy enough to improve the dwelling even when

there is knowledge. We see also frequently that there is energy

enough to make an imposing house, and not character enough to live

up to it. However, the builders of vitrified forts have not shown

themselves far advanced in architecture. They had no mortar for the

flat stones; still the vitrified method was by no means the only one

known, since vitrified parts are found over the built portion. We do

not know how much of the fort under notice was covered with

dwellings, but the eastern part had many loose stones; these were

taken down and used for building the houses now standing below. The

most important portion of the fort was that on the highest point, BB

(see Plate I.) Nature had provided a hollow between rocks to the

north and south of this spot and partly to the west, whilst a thick

wall of loose stones was made to the east. A good deal of this wall

remains, and has been cut through. This had fallen partly down, and

was raised up by using the material around, some of it consisting of

vitrified masses which had broken down. It shows a second

occupation.

Near the middle of

this were apartments with loose stone walls about two feet thick.

The drawing scarcely tells how broken down they are, and how

difficult it is at times to follow them. Four, however, were fully

made out, each rectangular; they are not vitrified, but follow the

rule in all these cases—a rule I mentioned before—not to vitrify

internal walls. The stones chosen are flattish, and no mortar was

used. South of these chambers are broken down walls with vitrified

pieces lying irregularly as if some walls had early fallen; a less

careful class of men had made their habitations there for a time,

living roughly, and leaving abundant evidence of their food in the

bones of sheep, pigs, and cattle.

There is a long

passage from the western side of this enclosure shown at a a,

and various confused evidences of other buildings are also found.

The passage is very narrow, and leads out to a fine open space at A

looking out to the sea, well protected by precipitous sides and by

vitrified walls in most parts, probably at all parts originally.

We may imagine the

central rooms to have been the apartments of the chief. Near the

surface were found querns very rude, and on the north wall at b,

the bronze ornament which I have already described. At the

north-west was found part of an iron sword, at c.

A sloping road exists

up the so-called Queen's entrance (Bealach-na-Bhan-Righ). I suppose

the whole to have been surrounded with a vitrified wall, or one

extending along the edge of the less precipitous part. The outer

walls have to a large extent fallen down the hill.

G is a large

vitrified mass, not connected apparently with any building, and I

have supposed it therefore to have been a tower. It is midway

between the two elevations into which the summit is divided by a

natural depression, although it does not itself stand in the most

depressed part; in reality it stands on a prominent part, by no

means the highest, although the most central.

C is a varied green

slope, on the edge of which near the precipice is a well, concerning

which romantic stories have been told, which stories I was

unfortunately compelled to prove to be founded on fancies.

D is varied, and

gives a variety also of small knoll and dale with rock. At E there

are indications of enclosures less formal than at B, BB. At one spot

there seems to have been a stone circle. F is a steep green slope

before the precipitous part begins.

It will be seen that

the digging was not continued all round, but in places sufficiently

numerous, I believe.

Here are a few

photographs, taken from different points, in order to show the style

of building. The view is put by the side of the plan to show the

relation of the parts, but is not so exact as the photograph from

the same point.

After all, the best

general observations regarding these forts are found in the small

volume by the discoverer of the first, John Williams, Esq.,

Edinburgh, 1777, and in the letter of the celebrated chemist, Dr.

Joseph Black, then Professor in Edinburgh University. The difficulty

of cementation by heat I have never seen, and I believe it need not

be much considered. Where basalt is abundant, and where so many

mixtures of silica with bases are readily found and made, abundance

of fuel will do the rest.

So far my task has

been to illustrate one fort only. I believe this is the first time

that a regular dwelling has been found in a vitrified fort, or

vitrified walls over "dry stone" ones. Of course we can always

distort every kind of evidence and speak of previous occupation as

being wonderfully far back, and no man can give a reply; but I

certainly find no evidence of anything existing in this fort to

prove that it belongs to very remote antiquity. Every trifle that

has been found points to times that need not have preceded European

history, so far as the skill is concerned, and it is unscientific to

imagine an age that is not demanded by the evidence. It would be

equally unwise to feel certain that the objects and the walls are of

the same date, but, taking the whole evidence together, I rather

think that a similarity of date is most probable; and when I read of

Mr. Anderson's searchings in the Picts' towers, and of the

introduction of strong thick walls of stone built without mortar, I

naturally think of them as made by people accustomed to thick walls,

and, either by imported advice or skill, beginning a new system,

seeing that wood was failing, and the old reckless use of it for

vitrifying purposes was impossible. That, of course, is a

conjecture, and as such it must be left for the present. It is a

reason for the Pictish towers following closely on the vitrified.

Since I examined

these remains I have looked at those in Rome, and it has surprised

me much to find how much that great city in imperial times was built

of rubble. Great buildings that astonish us, baths of Caracalla,

palaces of the emperors, great arches high and wide, were of

concrete and broken masses, and the half spans still hang with the

mixture hardened into one stone, almost like natural conglomerate;

remains of former houses broken up, with remains of statues, and

pieces of bricks, stones, marble, or otherwise, are all smashed

together, and the older Rome forms the material for the newer. The

buildings, to the very centre of the walls, are a type of the empire

itself, where nations were crushed, annihilated, or converted into

Romans, to all external appearance, until the outer form broke down,

and the real material showed itself. We may thus make these walls a

good lesson for the ethnologist.

The vitrified walls,

like the Roman walls spoken of, are a kind of rubble work, and this

way of building has a dignity which seems not to have been

considered sufficiently. Now, in modern times, it is coming again

into use, and we seem to be learning, as the Romans learned, that it

is extremely expensive to build with quarry stone, or even with

burnt clay or bricks, and some of our largest engineering, works are

being done with rubble and cement, or concrete. Some may think the

use of rubble to have arisen from the primeval habit of making a

mound of earth as a protection, a habit common among the Zingari of

Hungary at the present day, and seen abundantly in the raths of

Ireland. These form walls of enclosure, as common, probably, as the

walls to our farmsteads and gardens, and, as a culminating point,

ending in the earthworks or walls of the latest fortifications. We

can see here the natural growth of ideas, and it needs no

communication among nations to cause ideas to grow when the

materials and the wants, as well as the machinery, are the same in

each to an obvious extent. To determine to what extent they are the

same is not easy, but we cannot doubt that the use of earthworks

would occur readily to many. The use of cement, however, implies

invention; the early Romans did not use it; it became common only

when the greatest amount of building was required ; we have not used

it until lately, when the demands upon us for building material had

put us in a position similar to that into which the Romans were

driven when building increased so rapidly under the emperors.

If people were

accustomed to build with loose stones, it would be a very natural

wish to make them keep together; and if ever a beacon fire raged

unusually and burned a part of the wall into one mass by melting,

the discovery would be made. Still it requires invention, or at

least good observation, to see the value of such an accident; and

who can say if some wise stranger did not first find it out and show

the example,—some wise man coming from the East, and who had

lingered with his tribe in Bohemia, where also a vitrified fort has

been found? or shall we account for that Bohemian fort by imagining

some soldiers from Caledonia sent by the Romans over the Rhine, and

driven farther than was agreeable to them, making use there of their

old habits learned at home?

I throw together a

number of ideas, but cannot give yet a full examination. I am more

inclined to attribute the influx from time to time of the new ideas

to the immigration of strangers, whether wanderers or conquerors,

than to invention. Marauding has always been a favourite pursuit,

and it comes before merchandising. Some one probably came and showed

that the Caterthun system of building with loose stones was a bad

one, and showed how to build firmly, as on the Tap-o-Noth, and the

invention seems to have spread from near that part. Had these new

men come as great conquerors, they would have brought many people,

and we should probably have had some indication of them; but if they

came as wanderers, either marauding or selling, there might be few.

I am more disposed to think of a few dropping in at a time when

there would be little to steal; besides, at a later time, we have

new ideas coming into the east of Scotland, and resulting in the

peculiar Scottish sculptures. It is too much to suppose all to have

originated on the spot. It was most natural for people from

Continental Europe to .come to the cast of Britain first, because of

the distance of the western coast, and even from the Mediterranean,

it was more natural for navigators who kept near to the land to find

Kent than Cornwall. It was probably not until after a long

familiarity with the seas that the inhabitants of the Iberian

peninsula found out that it was really shorter to go to Ireland than

to the north of Britain, and probably, almost certainly, this would

apply to Cornwall and \Vales. Ireland, in the time of Tacitus, was

apparently pretty well known, although that historian has not taken

much trouble to describe it.

It is to be remarked

that the decided advances in the north of Scotland came after the

time of Pytheas, who leaves us an idea of great desolation and

poverty; whereas in Tacitus we have iron chariots, which indicate

many great strides in civilisation. It is quite possible to believe

an immigration to have taken place abundantly in those very early

times without our historic knowledge being affected, but it could in

that case be of only two races, Celtic or Scandinavian, if language

is to he our only guide. Small numbers would account for new ideas

and habits without change of tongue.

I did at one time

imagine that considerable numbers might have come and brought the

face so peculiarly Scottish, which is seen in considerable

perfection in the north-cast, or rather from Aberdeenshire to

Ayrshire; but now I am more inclined to look at the great extent to

which that face is spread in Scotland, and especially to see it

prominently in the Pictish districts. It may be an ancient

Caledonian peculiarity; where obtained is another question.

There is, of course,

a certain amount of fancy in these discussions ; but there are a few

more reasons which I hope to be able to make clearer for some of the

opinions. New ideas and habits seem to have come in along with the

peculiar physiognomy which characterizes so much of Scotland that it

may be called the Scottish. If the features referred to are

Caledonian, they separate that tribe from the Irish Scot and the

Kymry very distinctly. I hope I may be excused for giving this in

such hurried sentences; it is a subject that deserves much more

minute treatment, but one must only feel the way.

Numerous photographs

are very much wanted to illustrate Scottish ethnography. Many

varieties of face are seen in our country villages, but there is one

which a photograph only can explain, more frequently found in

Scotland than elsewhere, and perhaps nowhere else distinctly. |