John Mackintosh was born on the 7th of July, i868, in

the town of Dukinfield, Cheshire.

His parents were the children of

homely folk of upright character and industrious habits. His paternal

grandfather, William Mackintosh, came of a stock that hailed from

Inverness, and settled in Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire. They were much

reduced in circumstances. While still a child, William was carried daily

on the back of an older worker to a cotton factory, where he toiled from

four in the morning until eight at night. Those were the "good old days"

which preceded the passing of the Acts that put an end to child-slavery in

England.

Henry Burgess, the

maternal grandfather, was for years master of the British school in

Wellington Street, Dukinfield, and later a printer and stationer. He was a

man of strong literary interests, being a member of a band of

intellectuals locally known as the "Literary Twelve," which included

Samuel Laycock and several others who had skill in prose or verse. He was

keenly interested in politics and all that made for the public good, doing

much to secure the removal of a disadvantage from which Dukinfield

suffered through the lack of direct road connection with Ashton-under-Lyne. The river Tame, which divided the two boroughs, was passable only on

stepping-stones or through a ford. The present Alma bridge was built as

the result of a petition to Parliament which was engineered and presented in the House of Commons by a group of men of

whom Henry Burgess was chief.

There, on one side of the Tame, lived William and Hannah Mackintosh,

rearing their large family on hard work and plain fare; on the other

side, Henry and Martha Burgess reared a family as large, amid as difficult

conditions. Each couple brought to adult age a

group of children in sound health and imbued with good principles.

Both

families passed through the tremendous experience known far and wide as

the Cotton Famine. The outbreak of the American Civil War in the spring of

1861 caused such interruption of the supply of cotton as led to the

closing-down of many mills, and short-time in the rest. All the years of

the war the shortage continued. The pinch was felt in most homes,

including those with which we are concerned ; though in them certain

members had always some work to do. Wise steps were taken to prevent

discontent breaking bounds. Help was organised on a great scale.

Educational facilities were placed at the disposal of the workers. Grown

men and women went to school; some for the first time. They began with the

alphabet, and were taught reading, writing and arithmetic. Henry Burgess'

school was open to the out-of-works, and Mary Jane, afterwards the mother

of John Mackintosh, assisted her father in his self-imposed task.

One of

the men who took advantage of the educational facilities provided was

Joseph Mackintosh, the father of John. He saw in Mary Jane Burgess, not

the teacher only, but the wife that was to be. The teacher did not at

first smile on his advances; but inborn

resolution, coupled with native worth, ultimately prevailed.

Each was

attached to a place of worship Joseph to the Methodist New Connexion

Church in Stamford Street, Ashton-under-Lyne,

Mary Jane to the Albion Congregational Church in the

same town. At each Church a prayer-meeting followed the Sunday evening

service. Before their engagement both had been accustomed to stay for

prayer; and after becoming formally engaged, they agreed to continue the

practice at their respective churches. They did not enjoy each other's

society until the full round of Sunday duties was completed.

The young couple were married in July, 1865. The Cotton

Famine was over. The first loads of raw material had been brought in, the

people displacing the horses and drawing the vehicles through the streets

with rejoicing.

They began married life

humbly; but were not less happy on that account. The bride took uncommon

pleasure in the appointments of her home. She had a carpet in the living

room, an unusual thing in those days, when it was the rule to be contented

with the sanded stones of the floor. The kitchen chairs were of oak, with

smooth rush seats. Quite a feature was the big dresser, with its seven

drawers and centre cupboard, and its sycamore top scrubbed to a snowy

whiteness.

There was no honeymoon, and the

wedding gifts were neither numerous nor costly. There were dinner plates,

a china basin, a glass celery vase and salts, and a few other things. The

fashion of collective furnishing by friends was unknown, nor did their

friends possess the means for this. But if pride in home and joy in each

other be a chief asset of the newly-married, Joseph and Mary Jane

Mackintosh were rich indeed.

Into this home on

the 7th of July, 1868, came John Mackintosh. He was not the first child

born into it. The first to come (and to go' was Robert, who had but just

time to endear himself to his parents ere the call came which there is no

resisting. John, the second child, was to live on through one-and-fifty

strenuous years. A third son, now a minister in the United Methodist

Church, Rev. J. E. Mackintosh, of Derby, was born to the parents; then, in

succession, five daughters, three of whom are still alive, but two have

"fallen asleep."

A few months after John's

birth his parents removed to Halifax, then a growing town in the West

Riding of Yorkshire. An elder brother of his father, after whom John was

named, had undertaken the position of manager to Messrs. Bowman Brothers,

who had just commenced business there as cotton spinners. Looking round

for helpers, John Mackintosh could think of none more likely than his

younger brother Joseph, who, at his suggestion, entered the service of the

firm.

Wages in those days were not great. A

pound a week, or but very little more, was what the young couple had to

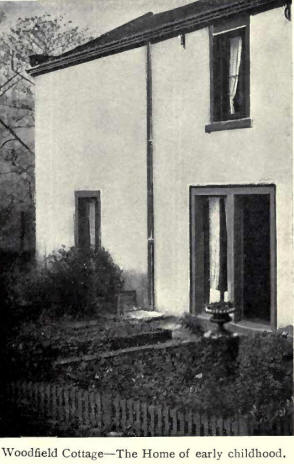

live upon. On this income, however, they lived comfortably. They secured a

home in Woodfield Cottage, a charming old house that had been subdivided

for the use of workmen and was situated in a pleasant lane near the mill.

A bright living- room looked out through French windows on to a pleasant

garden. The yard made a fine playground for the children. A large

summer-house, with a swing hanging from its central beam, was an unfailing

source of delight to the young ones. The mother was an excellent manager.

Limited as her income was, she managed to insure the lives of her

children, and to set aside a weekly sum for church and rent.

From the Stamford Street Methodist New Connexion Church, Ashton, the

membership of Joseph and Mary Jane Mackintosh was transferred to the Salem

Methodist New Connexion Church, Halifax ; not the stately Salem that now

stands on Nortth Parade, but "Old" Salem, as it was long affectionately

called. In connection with the building of new Salem the following

incident occurred. At a meeting of Church members called to consider

plans, Joseph Mackintosh, though earning little more than a pound a week,

promised five pounds towards the cost of the proposed-church. At a later

stage he promised a second five pounds, which, like the first, was

punctually paid. The remembrance of such things in later days, when the

children were old enough to understand, made a deep impression on them. It

accounts, in part, for the scale of the after-gifts of John to the church

he loved.

A further removal of the family followed the inclusion within

Messrs. Bowman's business of the large Union Mills in Pellon Lane. Joseph

was given charge of the three upper rooms of the new mill. This, besides

bringing increased income and responsibility, necessitated removal to the

west side of the town, which led the parents to transfer their Church

membership to the little school-church in Hanson Lane, the original of

what will be hereafter referred to as 'Queen's Road.'

It was in this new

sphere at Union Mills that Joseph Mackintosh's powers of management were

for the first time displayed. His natural force of character, and a

certain strain of sternness, made him a terror to evildoers. But he was at

heart resolutely just. He required from none a standard higher than the

one to which he himself conformed. For well-nigh fifty years he daily went

to and from the mills. Never was he late, though toward the end he took a

longer interval for rest at noon than was allowed to others. Always, wet

or fine, winter and summer, he was at his post by six o'clock in the

morning ; and within a few minutes of starting-time, he would go his

rounds. The iron door in the middle of the great room would be opened and

the slight form appear. Immediately all signs of levity ceased. The

flippant became serious and the idle industrious. The stern eyes took all

in. The bearing of the workers was an instinctive tribute to his

authority. His ascendency was complete. Men of the greatest technical

competence served under him, and also men of well-nigh untamable spirit

but there was not one who did not see in that quiet man his master.

When all went well he had apparently little to do. He

would be out of sight for hours. But if fire broke out, as it did more

than once or twice, there would be an exhibition of tempestuous energy,

and none would go nearer than he to the seat of the flames. If a rope were

weakened in the great rope-house, Mackintosh himself would repair it, and

repair it so well, and so fix it in its place on the mighty drum, that it

would transmit the drive of the engine to the machinery with a minimum

loss of power.

It was a lesson in patience and

in the art of observation to see him watching machinery with a view of

locating defects or of applying remedies. Wherever there was difficulty, a

breakdown, or danger, there was Joseph Mackintosh.

How he would have fared had Trade Unionism existed in

his day, one does not know. He served in the old days of individual

bargaining, and he served well. He would ill have brooked the harassments

modern employers have to face. He would have approved some developments,

but he would not have borne the dictation to which many in positions of

authority are now subject.

One phase of his

life impressed his 'family and all who knew him as heroic. As the result

of an accident in boyhood, which caused an injury to the roof of his

mouth, a malady developed which ultimately proved to be cancer. His

sufferings were great; but greater was the courage, the energy, the faith

by which they were borne. He felt he must not give in until his elder son

was launched in business, and his younger son seen through college. And

those who knew how racked with pain he was, how weakened with loss of

blood, how complete a stranger to ease of body and mind, could not see him

on his rounds without realising that here was a hero. The fact that he did

thus that others might have a better chance, made his sternness appear but

the shadow cast by inescapable calamity.

This

was the atmosphere in which John Mackintosh lived. Before his eyes daily

was an example of devotion to duty—stern and unbending devotion; of

business efficiency; of heroic persistency in work for the sake of others

when life was empty of pleasurable contentment.

John was not cast in the stern mould of his father.

There was more of his mother in him. He had his mother's brightness; her

kind ways her diffidence in saying 'No.' But in work he was his father. He

could toil strenuously. He could become a slave to the interests of

others. And when the suffering-time came, there was the same heroic

persistence to duty.

Not, like his father, did

he persist amid the clamour of machinery, but in the quiet of a managing

director's office, in public meetings, in Church courts and on the

magisterial bench. To those who knew him best, it was a relief that the

end came in the quiet of his own home, and not, as might well have been

the case, in the midst of some public function or business task.

Serving as the completest possible foil to his Spartan

father was John's mother ; his opposite, yet his complement, in all

respects. Though never a strict disciplinarian, she was able to get her

way with her children by the force of her kindly disposition. She believed

in a weekly half- holiday from school for her children—a popular enough

belief with them, though not always with the school authorities. She did

not allow her home-tasks to keep her from reading. She was younger than

most people of her years, and she deliberately kept young by loving young

things and having them always about her. She would even be guilty at times

of leaving occupations some would think should not be left, that she might

give the children a day in the country. And how they loved her for it I

She had a gift for story-telling, though not so great a gift as her

sister, 'Aunt Minnie,' who would come in of an evening and talk and knit

for hours. What tales Aunt Minnie told to the flashing of her needles I

She plied the children with romance and kept them in hose at the same

time.

The father was over-strict at times; the mother,

perhaps, not strict enough. But, whatever the parents' defects, the

children knew that first things were first with them. The father would be

in his place in church twice on a Sunday, and his family with him. The

children would be twice also in Sunday school; and this, not of

constraint, but from choice. And busy as the mother was, she was one of

the most effective and popular Sunday School teachers whenever the

exigencies of family life made it possible for her to attend. Time and

again she was appointed, at her own request, to the most difficult class

'in school. She had a way with her that few could resist.

Church and Sunday school meaning much to the parents,

it is not surprising that they came to mean much to the children. It made

all the difference that the parents led in matters of religion and duty.

The children were predisposed to value highly what was valued by the

parents.

John Mackintosh entered this

heritage, and his whole after life was coloured by it. The heritage was a

strenuous one. Modern views as to the limitations of labour were not yet

to the tore. He began his working life in 1878, when but ten years old,

working as 'half - timer' for the firm which his father and uncle served.

He 'had no sense of hardship in this, but was rather proud of it. Nor was'

his position singular. The majority of the boys about him began work at

the same age. The question of half-time was not then regarded as it is

to-day. The standards of education were not the same nor were the views of

liberty. Men did not know they were ill-paid or ill-used. Youth did not

know it. Children, far from regarding halftime as a hardship, were eager

to begin. It was only in later life that the price paid in hindered

education and, perhaps, arrested growth, was realised. However, the price

paid, in many cases, was not great. The work was not too hard. The rule

was kindly. The discipline of drudgery was not without good effects.

Muscles were hardened, self-dependence was encouraged, and, by resolute

pursuit of private study, a degree of self-culture that seems lacking in

the more highly favoured young people of our time, was not seldom

attained. The conditions were Spartan, the tests severe; yet those who won

through came often into a richer heritage than is realised in these days.

For three years John Mackintosh was a half-timer,

working six mornings of one week, from six o'clock until one in the

afternoon ; and five afternoons of the next, from two to five-thirty.

He had to 'pass' the doctor—a kindly veteran, whose way

was to regard the examinee with shrewd eyes, give him a playful poke in

the ribs, and send him back to his work with a bit of wise counsel.

John's first week's wage was half-a-crown, and big

money he thought it. Nothing he afterwards received seemed quite so

satisfying, or had about it the glamour of that first earned coin.

At thirteen years of age he became a 'full- timer,'

working thenceforward the full fifty-six-and-a-half-hours week then

customary.

He worked twelve years 'for Messrs.

Bowman Brothers, rising from the position of 'half-timer' to that of

'minder' of a pair of 'twiners,' as the 'doubling' machine of that period

was termed. It was hard work, and not, after the first novelty was gone,

in the highest sense congenial. The thought was often in his mind, as it

had been in his father's before him, to leave it and launch out in some

other line.

At an early age John Mackintosh

became engaged to Miss Violet Taylor, also of Halifax, who afterwards

became his wife. She was as closely attached as he to Queen's Road Church

and School; an attachment she still cherishes. Drawn together by common

interests, they manifested a preference for each other which quickly

ripened into love. Sharing John's religious interests and activities, as

she afterwards shared those of his business career, Violet was from

beginning to end a true helpmate, without whom John's life would have

lacked something of strength and grace.

The

home in which John was brought up, though that of a working man, was not a

poor one. His father's earnings, except in the first few years of married

life, ensured a sufficiency of life's good things. Always a little was

laid by weekly, which furnished the means eventually of purchasing the

house in which the family lived. Later, the father's earnings were

supplemented by those of the children. The continuation of these

conditions of comfort, however, was contingent on the father's state of

health ; and that, we have seen, was not good. Shortly after the departure

of the younger son for college, the father's health broke down. For months

he was seriously ill. Recovering in part, he again resumed his labours, in

the hope that he might make things easier for his children. But it was not

to be. He was at length compelled to acknowledge defeat, and about

midnight on April 30th, 1891, he passed to his rest.

It was at this most difficult time, with sickness

hanging over the home and himself largely responsible for home

maintenance, that the decisions were made which resulted in the

commencement of the business with which the name of John Mackintosh is

everywhere associated. During an interval of relief at home, John married,

and took possession of Hanover House, in King Cross Street, Halifax, where

his career as a 'manufacturing confectioner was begun. For a time he

continued to work in the mi1l, but at length he gave it up and ventured on

the move that was to bring him fortune.

Letters written to his brother, and happily still preserved, reveal the

stress under which these decisions were taken.' They show one considerate

of others, helpful in the parental home, and intent on serving the Church.

On December 5th, 1889, John Mackintosh wrote :-

Dear Brother,

I have just

an hour to spare, so I take this opportunity of spending it pleasantly and

profitably; for although we cannot talk face to face, our talk will be

none the less real. I am glad you have kept us in mind so much while you

have been away, and that your different surroundings have in nowise dimmed

your vision of home. In a very short time you will be amongst us again.

How we are all looking forward to the time! I expect we shall all look

much as we did when we parted, unless it be a trifle sadder on account of

poor father. I am sorry to say he does not improve much yet. He has been

rather better for a day or two, but to-day he has fallen off again. He is

quite conscious, however, which makes it nicer for us all. It has been

rather hard work for us while he has been rambling. He wanted so much

watching, but he has been quieter this last night or two. We have stayed

up with him every night since he left his work, but have divided the work

amongst us. V. and I stayed with him on Saturday night, J.W. and A. on

Sunday night. On Monday night V. and I stayed with him until two a.m.,

when mother relieved us. Tuesday. I went to bed till twelve, and I stayed

up Wednesday night. Sometimes he looks as if he would get better. At other

times it looks impossible. We shall have to leave it in God's hands to do

as He thinks best.

"Christmas is almost here

again. How the time flies. It only seems a few months since we were boys

together making a list for Santa Claus. What happy times we had in that

old attic in Rose Street! How the room has echoed with our laughter? How

our mother's blood ran cold at our yells and din? And how we simmered down

when father put in an unexpected appearance? Well, we are not much more

than lads yet, only life has begun to be a stern reality. We have our way

to make in the world. A few years ago life was only a dream. We had no

care, nor anxiety about our future. Now we have to form plans on which to

build. We are often puzzled as to what is the best thing to do, but having

formed our plans, I pray that we may have strength to carry them out; and

that God will bless our lives, if not with abundant wealth in the things

of this world, then with abundance of grace and love for our heavenly

Father.

'I hope as each Christmas comes round, we shall get more

like Him, whose birthday we shall soon be so glad to welcome as Bringer of

peace and goodwill to all men.'

The remainder of the letter contains

news of Church and Sunday school. He is getting up a programme for a

concert and asks his brother's aid. He reports the doings of the 'Mental

Culture Class' and the successful visit of a missionary from China. Then

he adds:-

'I have exhausted my paper, and more

than my hour; and, like you, I have more to say. But I shall have to

submit to the inevitable and bring my letter to a close. I am writing this

in J.W. 's.; H. is here with me. We are keeping each other company. She

sends her love, as do Violet, Father, Mother and all at home.

Your

loving brother,

JOHN.'

The next letter was written sixteen months

Later. The father had recovered from his earlier illness, had returned to

work, and had again broken down. The writer of the letter had married in

the interval; had begun business on his own account ; and had decided

henceforth to depend wholly on his own efforts. The letter is a

characteristic blend of business courage, family feeling, and Christian

faith.

24/4/1891.

Dear James,

I was at our folks last night and promised to write to

you. I think this will be in place of sister's usual letter. I shall

have to be brief, as I have only a few minutes to spare. I shall be

leaving Bowman's on Thursday noon. I shall then have worked my notice.

You see. I am going to risk it. After considering all the points, 1 came

to the conclusion that the above course was the only one that ,as likely

to succeed. I should have liked to have kept on at the mill at least

another twelve months had things been different. We shall have to be

determined now to make things go.

"I suppose that sister told you in

her last how very ill father was. He is still sinking. I am afraid what he

said to you when you left about not seeing you again on earth is going to

prove true. We are expecting every day to be his last.

He has scarcely eaten anything for over a week; nothing at all since last

Friday. He has not strength enough to raise himself in bed. He is almost

continually repeating verses of Scripture, and he talks about going home

in such a splendid manner. He is quite different from what he was a while

back. He likes us to talk about Heaven, and the rest there will soon be

for him. He does not want to get better; all he is waiting for is Jesus.

He is not afraid to die. It is grand to think that, if we only will, we

may meet him again in health and strength.

"He

has been a good father to us, and I believe what has made him cling to

life so, is his desire to see us all get a good start in life. He was only

saying to me on Sunday, he had hoped to see you through college and me

fairly into business. And he said he hoped we should help one another all

we could. I promised to do all I could to help you.'

The father died two days later. The business venture

was abundantly justified by results. The promise made by the father's

bedside was fulfilled.