A PLEASANT tour from Haddington is

by East Linton and Whitekirk, then round by the coast, Tantallon and the

Bass, to North Berwick. After East Linton you keep on the left bank of the

Tyne. At Tyninghame you note the charming cottages almost buried in

flowers. East Lothian is far before most of Scotland in the neatness of

its peasant homes. Elsewhere you come on choice bits that prove the

Cottagers of

Glenburnie no false picture, but not in this

pleasant countryside. After Tyninghame the highway runs through a fine

stretch of woodland. Of old this was bare moor, but the sixth Earl of

Haddington, at the beginning of last century, set to work to plant on a

great scale. As one master schemed and directed everything was done with

method. Great avenues of trees led to a glade, and thick holly hedges rose

in double walks or avenues, now alone and again interspersed with other

trees. The late Queen was here in 1878 and confessed it reminded her of

Windsor and Windsor Forest. Her Majesty was happy in her visit. Three

years afterwards, on the 14th October 1881, a storm of almost inexplicable

violence burst on the forest, destroying some 30,000 trees and marring the

symmetry of the whole. It is still pleasant, but if the best of it be seen

from the highway, it is not to be compared with many an English sylvan

scene. You are no sooner out of the wood than you climb a little hill into

Whitekirk, the church whereof, with its square tower and antique porch,

has come down from distant days less injured than is usual in the north.

It has a notable record. Its first legend is that of St Baldred of the

Bass. In the eighth century he flourished—one might irreverently say

vegetated—on the Bass, where he stuck close as limpet to rock—was hermit

there, in fact, for ever so long. Finally he died in the odour of

sanctity, whereupon the three parishes we have just traversed -

Prestonkirk, Tyninghame and Whitekirk—contended for his remains. Things

looked serious, for relics were then held valuable assets, but the

spiritual guides urging their flock to take rather to their devotions than

their fists, surprising results ensued. Three St Baldreds were found next

morning instead of one, so like that there was literally not a hair to

choose between them. The parishes had one a-piece.

The church was dedicated to the

Virgin Mary, and Our Lady of Whitekirk was a person of great repute in

mediaeval Scotland. When Edward III. invaded in

1356 some sailors

from the fleet wandered up here, and one of them impiously plucked a ring

from Our Lady’s finger. Down crashed a crucifix on his skull and stretched

him lifeless on the floor. The tars stripped the church, nevertheless, but

the ship that bore away the spoils was presently lost on the sands of

Tynemouth. Some eighty years afterwards Æneas Silvius made his famous

visit to Scotland. In a pilgrimage to Whitekirk in the depth of winter,

with more piety than prudence, be trod barefoot ten miles of frozen

ground. Long afterwards, when as Pope Pius II. he ruled the Church, many a

gouty twinge in his poor feet hindered him from forgetting that far-off

shrine by the Northern Sea. This Pope was a Piccolomini. The family which

gave two Popes to the Church had, and still has, its seat in Siena. Our

pilgrim enriched the cathedral of his native town in one way and another.

You see in the library a fresco by Pintoricchio, representing James I.,

the King of Scots, receiving the future Pope on his aforesaid visit, and

the background is a landscape. If it be East Lothian it is highly

idealized, for the vine and the myrtle are not plants indigenous to that

soil. There is an imposing-looking barn just

behind the church—some sort of monkish grange, no doubt. There it is

ridiculously averred Queen Mary spent two nights. Queen Mary was a good

deal about those parts. She probably hunted or hawked over every mile of

them, but why she should have put up at a barn, when she had a choice of

Hailes and Dunbar within easy reach, it were hard to say. In the

churchyard there is this odd epitaph on a youth of nineteen who died in

1805: "We can say this without fear or dread that he was one that feared

God and an ornament to society." In epitaphs most of all a little learning

is a dangerous thing. The sign-post here is misleading. It indicates a way

to North Berwick which is hilly and comparatively uninteresting, though

the shorter as far as space goes. Better to go right opposite for that

will take you pleasantly round the coast, which you join just where the

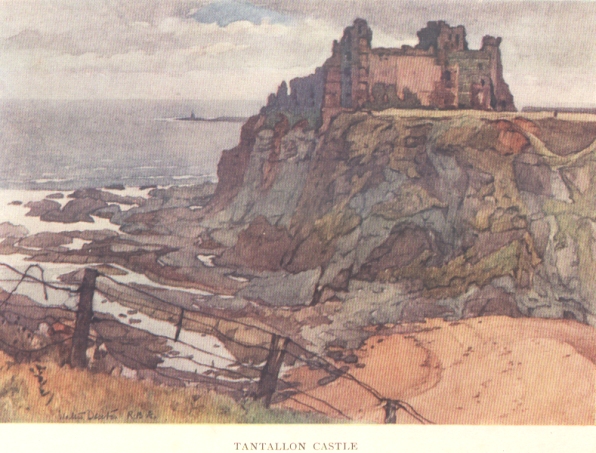

old castle of Tantallon stands on its cliff facing the Bass Rock.

Tantallon to-day is a show place.

They charge for admission and it is carefully kept up. I have no doubt the

money is used for needful repair and watching, but Tantallon, like a

hundred other places, was more enjoyable when you went about it as you

liked and there were few visitors and no hindrances. But then North

Berwick and the places about it had not "arrived" in so tremendous a

fashion. Tantallon is the limit of the ordinary tourist stream. There is a

continual coming and going of traps of all sorts, not only between it and

North Berwick but right on to Edinburgh. Tantallon has all the interest a

ruin can have. Its situation is delightful, its history exciting. Genius

has touched it with magic wand. It stands on a great cliff over the Firth,

there opening into the North Sea, and right opposite is the great Rock, a

couple of miles out, you learn, though it appears quite close. The outer

walls of Tantallon are so entire that you would hardly call it a ruin.

"Three sides of wall like rock and one side of rock like wall" is Hugh

Miller’s admirable description. It is a mere shell, but even were it

otherwise ruins look best from the outside. There is a dovecot near at

hand. The "ducat" is a marked feature of the Lothian landscape. They do

not build them now. I think all I ever saw look considerably over a

century old. Perhaps wood pigeons are so plentiful that they do not repay

the trouble. Tantallon is bound up with the fate of one family though it

be no longer theirs. In history and romance it must always be the property

of the Douglas. With good eyes and good will you can still trace the

bloody heart above the gateway. You remember how the good Sir James set

off to carry the heart of the Bruce to the Holy Sepulchre, how be died on

"a blood-red field of Spain," and how his master’s heart and his own body

were brought back to Scotland for burial. Hence the sign in the shield.

This poor shell was once deemed of fabulous strength.

"Ding doun Tantallon,—

Mak’ a brig to the Bass,"

was old Scots for impossible. Its

origin is unknown, but probably the great siege it sustained in autumn of

1528, against

James V., aided by a park of the most powerful artillery of the day,

including "Thrawnmouth’d Meg and her Marrow," gave it reputation. Here

grim old "Bell the Cat" had his lair, so that it was "deemed invulnerable

in war." Two names in literature are connected with this old fortress.

Gawin Douglas, Bishop of Dunkeld, "who in a barren age gave rude Scotland

Virgil’s page," was born here in 1474. He prefixes his translation of each

book with a wonderful prologue, quite Chaucerian, marked by delightful

appreciation of natural scenery. He drew those pictures with the Lothian

fields before his eyes or his mind. One graphic line of his,

"Gousty schaddois of eild and grisly deed,"

would, as Hugh Miller says, have marked him poet though

he had never written another word. And not less is Tantallon bound up with

the name of Scott You know from Marmion how Lady Clare paraded the

garden and the battlements. That famous poem is in the mind, or the mouth,

or the pocket at least of all who pass by, and there is no need for

quotation. The modern author does not always magnify his office. Scott

thought literature scarce part of the real business of life. The

ingenious R. L S. has expressed the same opinion. Both have placed the

writer far below the warrior and the builder. It would have been

interesting to know what old-time Gawin thought about it. Old "Bell the

Cat" at least bad no doubts:

"Thanks to St Bothan, son of mine

Save Gawin ne’er could pen a line!"

Is Tantallon haunted? A place with such memories ought

to be, but the only story is one a century old and altogether comic. A

rascally shipwrecked sailor, a Scots David Pew, in fact, took up his abode

with some comrades and robbed right and left, but always during the night

time. Noises heard at dark in the old ruins were naturally set down to the

devil. Only when the old salt’s scarred and grim visage, surmounted by a

Kilmarnock night-cap, was seen, the very embodiment of the actual, was the

truth divined. The castle was stormed for the last time and the band

routed and dispersed.

And now, brig or no brig, we must get us over to the

Bass. It stands 420 feet above the water, one huge mass of homogeneous

trap, as Hugh Miller tells us. You are taken over from Canty Bay, a small

hollow in the cliff which is, and always has been, the port for the Bass.

You will choose a reasonably calm day for your pleasure excursion. There

is but one landing-place. The Bass is all precipice except one side, and

this slopes down from the top. Near the bottom it narrows. A fortification

is built across, and below this is the small platform on which you land.

You peer into the prisons of the martyrs and climb up to the little ruined

chapel which goes by the name of St Baldred’s cell, and so on to the top.

You note the heavy red-coloured flowers, the tree-mallow, and there are

the sheep and the thousands and thousands of sea-birds with their hoarse

call. One little change recent time has brought. A lighthouse has been

built, and after many years the Bass has again a resident population. Some

effects of wind and weather on Tantallon and the Bass are very striking,

as at sunset, when the shadow of the great rock stretches for leagues over

the sea; or, again in still moonlight, when Tantallon seems a fairy

castle; or yet again in a great storm, when the ocean rollers dash spray

and foam far up those rocky sides and make the mass shake and echo till it

reels on its base.

Here is R. L. S. with an admirable impression. "It was

an unco place by night, unco by day; and there were unco sounds; of the

calling of the solans, and the plash of the sea, and the rock echoes that

hung continually in our ears. It was chiefly so in moderate weather. When

the waves were anyway great they roared about the rock like thunder and

the drums of armies, dreadful, but merry to hear, and it was in the calm

days when a man could daunt himself with listening; so many still, hollow

noises haunted and reverberated in the porches of the rock." There is a

bore or cavern right through the Bass, which at low tide it is possible to

traverse. The opening is half blocked up by a rock. It is 100 feet in

height to start with, but it narrows down presently, and in the middle is

a dark pool. As it twists you do not see right through. It is dark, damp

and dismal. It goes right under the ruin of the old chapel, and through

and back again is somewhat under a quarter of a mile.

The Bass, like Tantallon, has a romantic history. First

comes St Baldred, to whom the little chapel may be said to belong, though

it is centuries after his time. The story we have told shows his

reputation for sanctity. He wrought miracles in his life as well as at his

death. Thus a rock which inconveniently stood between the Bass and the

shore floated at his command to an out-of-the-way cliff and was henceforth

known as St Baldred’s Cockle Boat, and there is St Baldred’s Well, and St

Baldred’s Cradle, and St Baldred’s Statue and what not. Later, the place

was held by the ancient family of Lauder of the Bass. One of them fought

in the Scots Wars of Independence, and they had touch with the Rock for

about five centuries. Their arms were a solan goose with the legend,

Sub umbra alarum tuarum, which strikes you as exceeding irreverent,

but meant no more perhaps than that they derived considerable profit from

the birds. The island was a prison and fortress. A sure holdfast! Even if

you broke your cell, how to get away from the rock? The first prisoner

mentioned is Walter Stuart, son of the Duke of Albany, regent during the

captivity of James I. He and his father and one of his brothers were

beheaded, and their heads shown to their mother, then a prisoner at

Tantallon. The old lady controlled her feeling. "They died worthily," she

said," if what was laid to their charge was true." But the prisoners of

the Bass were those confined on it fifteen years or so before the

Revolution for their adherence to the national faith—the covenanting

divines, in other words. "Feden the Prophet" was sent here in June 1763

and remained for four years, "envying with reverence the birds their

freedom." Most grievous the prison to him of all men, for he had roamed

far and wide over the wild hill districts of the south, and though be

complained that he had got no rest in his life it is not like it was such

rest he desired. How admirably the stem, gaunt figure is touched off in

Catriosa: "There was never the wale of him sinsyne, and it’s a

question wi’ mony if there ever was his like afore. He was wild’s a

peat-hag, fearsome to look at, fearsome to hear, his face like the day of

judgment. The voice of him was like a solan’s and dinnle’d in folks’ lugs,

and the words of him like coals of fire." And again: "Peden wi’ his lang

chafts (Jaws) and lunten (glowing) een, and maud (plaid) happed about his

kist, and the hand of him held out wi’ the black nails upon the

finger-nebs-—for he had nae care of the body." Another of the prisoners

was Thomas Hogg of Kilturn. He had incurred the special enmity of

Archbishop Sharp, who ordered that if there was a place in the Bass worse

than another it should be his. The cavern "arched overhead, dank and

dripping, with an opening towards the sea, which dashes within a few feet

below" was his gruesome lot. This was the donjon keep of the old fortress,

and a very prison of prisons. James Fraser of Brea is another name. In his

Memoirs he has left a somewhat minute account of the place and his

life. He notes the cherry trees, "of the fruit of which I several times

tasted." He tells that the sheep are fat and good, and asserts that a

garrison of twenty or twenty-four soldiers could hold it against millions

of men. Another martyr, John Blackadder, was most worthy of that name,

since he died in confinement. His tomb and its inscription are still to be

seen in North Berwick kirkyard. You do not wonder men died, rather that

they could there exist. The rooms were full of smoke, they had sometimes

to thrust their heads out of the window to get a breath of air. They were

often short of victuals, for in wild weather no boat dare touch the place.

All was damp and unwholesome. It was horribly cold during most of the

year. Two lighter touches relieve the picture: "they were obliged to drink

the twopenny ale of the governor’s brewing, scarcely worth the halfpenny

the pint," and there is, or was, a huge mass of debris made up of "the

decapitated stalks and bowls of tobacco pipes of antique forms and massive

proportions." Every smoker will understand what a consolation tobacco was

to the small garrison chained to the rock.

With the Revolution of 1688 the history of the Bass

draws near a close. It held out some time under Sir Charles Maitland, the

depute governor, but surrendered in 1690. Then it was used to confine

Jacobite prisoners— four young officers, in fact, taken at Borrodale.

These ingeniously managed to turn the tables on their gaolers, whom they

packed speedily ashore. By what their enemies called piracy, and

themselves legitimate warfare on passing vessels they managed to support

themselves very well and annoy the Government very greatly. They

capitulated in April 1694, on favourable terms, for by repetition of

well-known tricks they persuaded the enemy they were great in numbers and

well supplied. Then the old fortress was dismantled, and in 1706 it was

granted to Sir Hugh Dalrymple, President of the Court of Session, and it

is still held by the descendants of that astute lawyer.

One cannot leave the Bass without saying some words

about its constant inhabitant, the Solan Goose. At one time it was thought

that only here and at Ailsa Craig were these birds to be found. This is

long exploded, but the Bass is one of their few strongholds.

Old Hector Boece has many wonderful things to say of

them. They bring so much timber to the island for their nests that they

satisfy the keeper for fuel. He ungratefully robs them of their prey, for

they have a nice taste in the way of fish, and appropriates their young.

For themselves, their fat is made into "an oile verie profitable for the

gout and manie other diseases in the haunches and groins of mankind."

Hector avers that common people are much mistaken in believing that these

geese grow upon trees, "hanging by their nebs, as apples and other fruits

do by their stalks," the fact being that when trees fall into the sea they

become gradually worm-eaten. Now if you look at the worms very closely you

see they have hands and feet, and finally "plumes and wings." In the end

they fly away— Solan Geese! The witty author of Hudibras must have

heard of these theories.

"As barnacles turn solan geese

In the islands of the Orcades."

It is difficult to believe that Solan Goose was ever

looked upon as a delicacy, but Ray, the botanist, was in these parts in

August 1661, and he tells us that the young are esteemed a choice

dish in Scotland and a very profitable source of income to the owner of

the Bass. As he ate of them at Dunbar he ought to know. But there is still

better authority, since an act of the Scots Privy Council in 1583,

ratified by an Act of the Scots Parliament of 1592, declared them to be

"apt for nutriment of the subjects of this realm." Also the minister of

North Berwick, who is officially vicar of the Bass, is entitled to twelve

Solan Geese per annum, which gives him a month to digest each bird. It is

averred a one-time innkeeper of Canty Bay used to supply them when a

beefsteak was ordered, and that the guests only found out when told. That

innkeeper had a very pretty wit, but this cuisine pour tire was a

dangerous experiment. You easily believe the story, for as you swallow

your Solan Goose you hesitate as to whether you are eating fish, flesh or

fowl, or a combination of two, or all of them. I have never heard that the

Solan Goose is served up at the various palatial hotels which abound on

the near coast. The Bass has other marvels: "that herb very pleasant and

delicious for salad" which is of no good anywhere else; that stone which

has the property of changing salt water into fresh; that still delicious

mutton, surely the best gjgot du pre salé