“Gin ye should come to Anster fair,

Speir ye for Maggie Lauder.”

Anstruther is cut in

twain by the Dreel Burn. Each portion is’ a distinct burgh, and is managed

by a separate Town Council. East Anstruther is a parish as well as a

burgh; but the parish is exceedingly small, containing barely 57.5 acres,

of which nearly 32 are fore-shore. As its name implies, it lies on the

east side of the burn. It, again, is divided from Cellardyke by Caldies

Burn, which, being now covered in, flows underneath a wynd at the far end

of the East Green beyond the Baptist Church.

Name and Antiquity.—This

town, like most others in the olden time, had its name spelt or mis-spelt

in many ways. Indeed, there may be said to be two ways yet; for locally,

at least, it is commonly called Anster. Some of the former spellings were

:—Eynstrother, Aynestrothir, Ainestrother. and Ansteruthyir. Struther is

said to signify a place lying in a valley, as Anstruther does. Others have

held that it means a low marshy place, and although it is “now tolerably

dry, there are proofs that at one time it must have merited such an

appellation.” Wood, in his East Neuk of Fife, says that, “the ancient form

of the name Anstruther is Kynanstruther, the meaning of which is, ‘the

head of the marsh,’ or, as some say, ‘the head of the shoulder.’” And

Conolly, in his Fifeiana, states that the earliest form in which it is

written is “Kinstrother,” and that it occurs in the Chartulary of Dry.

burgh, in a passage dated 1225. Wood does not say where he got the ancient

form of the name. Perhaps it was from the same source as Conolly. The

latter writer is certainly right to some extent. The name does occur in

the Chartulary of Dryburgh, under the year he mentions, and is there

begun with a K. The MS. of that Register, however, is written in a hand of

the sixteenth century, and in it there are numerous errors in the names of

persons and places. It was printed for the Bannatyne Club, and the learned

editor refers to the deed in question, in a foot-note to his Preface,

where he says that the name “has been erroneously written Kinstruther,

instead of Einstruther.” The same document occurs in the Chartulary of St

A ndrews Priory, where it is written in a fourteenth century hand, and

there it is spelt, not Kinstrother, but Eynstrother! The origin of the

town is unknown, but it goes back for more than six centuries, for in or

about 1280, Henry of Anstruther gave three booths in his town of

Anstruther to the monks of Dry-burgh.

Royal Burgh.—Anstruther

Easter was only a burgh of barony, until James the Sixth erected it into a

free royal burgh, in, it is said, 1583. The bailies, council, and

community of Anstruther be east the burn sent in a supplication to the

King and Parliament, in 1585, praying that—as his Majesty had erected

their town into a royal burgh, and “dotit” it with sundry privileges and

liberties—this Parliament might ratify the charter, so that it would stand

in all time coming. Their petition was granted, with the provision that it

would in no way be prejudicial to the rights of Crail, or to the action

which they already had or intended to bring against Anstruther before the

Lords of Council and Session. In 1587, the King and Estates considering

how profitable the erection had been to the common-weal of the realm, and

especially to the royal burghs in paying “extentis and imposts” with them,

confirmed the erection anew, that their privileges and liberties might be

“bruikit” by the present inhabitants and their successors as freely as any

other free burgh royal. On the same day, James Geddy, a burgess of Crail,

protested before King and Parliament that this confirmation should not be

prejudicial to the rights of Crail.

James Melville’s Manse.—In

the old Statistical Account of East Anstruther it is stated that formerly,

although “the church was at Kilrennie, the minister resided at

Anstruther, and was styled the minister of that town.” From Melville’s

Introduction to his Diary, which is dated at Anstruther the 10th of August

1600, we learn that “Mr Wilyeam Clark, of maist happie memorie for

godlines, wesdome, and love of his flok,” died, in 1583, “leaving four

congregationes, ‘wharof he haid the charge, destitute of ministerie —

viz., Abercrombie, Pittenweim, Anstruther, and Kilrynnie.” Patrick Adamson

obtruded Robert Wood on them, of whom, says Melville, “they lyked

nathing.” At the earnest desire of the Presbytery, and the congregations,

Wood was succeeded by Melville, who “enterit in the simmer seasone, in the

monethe of July 1586, to teatche at the kirk of Anstruther, situat in the

middes of the said congregatiounes.” This kirk was, of, course, the Parish

Church of West Anstruther. No congregation was ever blessed with a more

conscientious or painstaking pastor. Although he had taken Robert Dury

with him as a fellow-labourer, he soon found the four congregations “a

burding intolerable and importable, with a guid conscience ;“ and

therefore set himself to separate them, and provide each with a minister,

“resolving to tak him self to Kilrynnie alean.” This he managed to

accomplish in three years. The stipend of Kilrenny at that time was only

£80 Scots, without either manse or glebe, but the people raised it to 400

merks, and obliged themselves to build him a house on a piece of ground,

which the Laird of Anstruther had freely given for that purpose. “This,”

he says, “was undertakin and begoun at Witsonday in anno 1590, bot wald

never haiff bein perfyted, giff the bountifull hand of my God haid nocht

maid me to tak the wark in hand my self, and furnisched stranglie to my

considderation all things neidfull; sa that never ouk (i.e., week) past

bot all sort of warkmen was weill peyit, never a dayes intermission fra

the beginning to the compleitting of it, and never a soar finger during

the haul labour. In Junie begoun, and in the monethe of Merche efter, I

was resident thein. It exceides in expences the soum of thrie thowsand and

fyve hounder marks; and of all I haid nought of the paroche, bot about a

thrie thowsand sleads (i.e., sledges) of steanes, and fourtein or fyftein

chalder of lyme; the stanes from the town, and lyme from the landwart,

skarslie the half of the materialles, lyme and stean, and thairfor justlie

I may call it a spectakle of God’s liberalitie.” After getting into his

manse, Melville “becam mikle in deat,” as his 400 merks fell far short,

and a great part of it was “unpleasandlie peyit, and out of tyme.” But

although Edinburgh, Stirling, Dundee, and St Añdrews eagerly desired him,

he would not leave his attached flock. The Commissioners of the Plat, in

1590, gave him an aug mentation of £80, and next year four chalders of

victual. By a most unselfish bargain, which he made with the Laird of

Anstruther regarding the teind fish, he relieved his parishoners and

secured the stipend for his successors. “His whole conduct in this

affair,” says M’Crie, in his Life of Andrew Melville, “exhibits a rare

example of ministerial disinterestedness, which, in this calculating age,

will be in danger of passing for simplicity, not only with the secular

clergy, but with those whose spirituality is so exquisitely sensitive as

to shrink from the very idea of a legal or fixed provision for ministers

of the Gospel.” In speaking of the manse, David Swan, the writer of the

New Statistical Account of East Anstruther, says :—“ It remains to this

day, with very few alterations, and these only in the interior, if we

except a paltry addition made to it by a former minister, not at all in

the substantial style of the original building. The situation is

remarkably well chosen; the walls are of great thickness ; the lower

storey consists of three vaulted cellars; the ceiling of the apartments in

the second storey is as lofty as in most modern buildings; that of the

third much less so. A staircase, in the form of a round tower, is carried

up the whole height of the building, at the top of which there is a small

apartment, commanding a very fine prospect, and having on the outside,

chiselled in stone, these words—’ The Watch Tower.’” The manse is enclosed

by high walls; but from the wynd, which passes on its west side, the panel

bearing the inscription can be seen high on the square tower.

As has been already

mentioned, under Kilrenny, Beat, who wrote 46 years before Swan, claimed

Melville as the builder of his manse, and affirmed that “The Watch Tower”

was also hewn on one of its upper windows. It is difficult to see why lie

should have built two manses in what was then one parish, and he himself

only mentions the building of one. Beat’s manse was probably erected

after East Anstruther was disjoined from Kilrenny. Hew Scott says, that

Colin Adam, who was appointed minister of Kilrenny in 1634, lived like his

predecessors in East Anstruther; and he was the first minister of it after

it was made a separate parish, and there he died in 1677. He was succeeded

in Kilrenny by Robert Bennet in 1642. Conolly, who from his official

position had the best means of clearing up such a point, says, that about

1637 the old manse was sold by Melville’s eldest son Ephraim, to the Laird

of Anstruther, for a manor house; and after Anstruther Hall or “The Place”

was built, the manse was occupied by the dowager ladies, and other

relatives of the succeeding lairds, until 1713 when, under the name of

“Lady Melrose’s House,” it passed into the hands of the Town Council,

being excambed for an old tenement in the Pend Wynd, which had served as a

manse for the new parish ; and ever since then it has continued to be the

property of the burgh and to he occupied as the manse. Although it is well

nigh three centuries since the venerable house was built, yet it is ever

associated with him, who was its saintly occupant for its first sixteen

years. His was not a long life, but there was much active service and much

patient suffering crowded into it. He was born in 1556 or 1557, and began

to preach when he was only 18. One year afterwards he was a regent in

Glasgow University, and was the first regent in Scotland to read the Greek

authors with his class in the original language. In 1580 he was chosen

Professor of Oriental Languages. in St Andrews University; and in 1587 he

removed his wife and family from St Andrews to Anstruther, which was the

twelfth time he had flitted since he was married four years before. Having

been invited to London by James the Sixth, he and his famous uncle Andrew

sailed from Anstruther on the 15th of August 1606. The treacherous and

unworthy conduct of the King towards them is well known. James was warded

at Newcastle and afterwards at Berwick. His bereaved parishioners

earnestly petitioned that he might be allowed to return, but in vain. As

he would not give way to the plans of the King, even though tempted by the

offer of a bishopric, he was forced to remain in exile, where he married a

second wife, and where he died in 1614. When minister of Kilrenny, “he

paid the salary of the schoolmaster out of his own purse; and as the

parish was populous, and he was often called away on the common affairs

of the church, he constantly maintained an assistant.” His diary has been

printed both by the Bannatyne Club, and the Wodrow Society; but as it is

extremely interesting, and valuable in many ways, it is to be regretted

that no edition has yet appeared with the spelling so far modernised that

it would be thoroughly intelligible to the great body of the people.

A Brush with Pirates.—An

Anstruther crear, or sloop, returning from England, was pillaged by

pirates and “a verie guid honest man of Anstruther slean thairin.” The

same piratical English craft was afterwards audacious enough to come to

“the verie roade of Pittenweim,” and there to spoil a ship and abuse the

crew. This was more than the Anstruther folk could stand. Having,

therefore, purchased a commission, they speedily rigged out a

swift-sailing vessel, which was manned by nearly all the honest and best

men in the town. The captain is described as “a godlie, wyse, and stout

man.” After sailing they met their Admiral, “a grait schipe of St Androis,

weill riget out be the burrowes,” and which was also a fast-sailer. These

two vessels made every ship they met strike and do homage to the King of

Scotland. One proud, stiff Englishman refused to do reverence until his

main-sail was carried away by a shot, and then it turned out that he was

only a merchantman—not a pirate. But proceeding to the coast of Suffolk,

they found “the lown” they were seeking, in the very act of plundering

another Anstruther crear which he had just taken. The pirates seeing that

they were pursued, ran their ship on land. The Anstruther fly-boat dashed

after them, fired a broadside at “the lownes,” and landed a party who

captured six of them. The gentlemen of the country and neighbouring towns,

alarmed by the shooting, supposed that the Spanish Armada was upon them,

for this happened in 1587. But, when the Justices of the Peace saw the

Scottish arms, with “twa galland schippes in war-lyk maner,” they gave

reverence, and allowed them to take their prisoners and pirate ship,

which, with flags, streamers, and ensigns flying were brought to

Anstruther, within ten days from the time they had set out. Four of the

pirates were hanged at St Andrews, and the other two on the end of

Anstruther pier. James Melville winds up his account of the event by

saying that it passed off “with na hurt at all to anie of our folks, wha

ever sen sync hes bein frie from Einglis pirates. All praise to God for

ever. Amen.” In course of time, however, the pirates grew as bold as

before.

The Spanish Armada.—It

is impossible now to realise the anxiety and terror that the threatened

Spanish invasion inspired in Britain three centuries ago. The news of the

“Invincible Armada” was long blazed abroad. Terrible, says Melville, was

the fear, piercing were the preachings, earnest, zealous, and fervent were

the prayers, sounding were the sighs and sobs, and abounding. were the

tears, at the Fast and General Assembly, kept at Edinburgh in August 1588,

when the news were credibly told, sometimes of their landing at Dunbar,

sometimes at St Andrews, and the Tay, and now and then at Aberdeen and

Cromarty. At that very time, the Lord of Armies, who rides on the wings of

the wind, and keepeth His own Israel, was convoying the monstrous ships

round our coasts, and dashing them to pieces on the headlands and islands

of the country they had come to destroy. Early one morning, one of the

Anstruther bailies came to James Melville’s bedside, saying, “I have to

tell you news, sir. There is arrived within our Harbour this morning a

ship full of Spaniards, not to give mercy but to ask it.” The commanders

had landed; but the bailie ordered them to their ship again until the

magistrates had considered the matter, and the Spaniards had humbly

obeyed. Melville hastily arose, and, assembling the honest men of the

town, came to the Tolbooth. After some consultation, “a verie reverend man

of big stature, and grave and stout countenance, grey-heared, and verie

humble lyk,” was brought in, who, “efter mikle and verie law (i.e., low)

courtessie, bowing down with his face neir the ground,” and touching

Melville’s shoe with his hand, explained that King Philip, his master, had

fitted out a navy and army to land in England for just causes, to be

avenged of many intolerable wrongs he had received from that nation ; but

God for their sins had been against them, and driven them past the coast

of England ; and he, being the general of twenty hulks, had been wrecked

at the Orkneys. Those who had escaped from the merciless seas and rocks,

had suffered great hunger and cold for more than seven weeks, until now

they had come here to kiss the hands of the King of Scots—at this point he

“bckkit” even to the earth—and to find relief and comfort to themselves.

Melville’s staunch Protestantism and kindly nature were alike conspicuous

in his reply. The commander said that he could not answer for his Church,

but he had shown kindness to several Scotsmen at Calais, and some of

these, he supposed, belonged to Anstruther. The bailies resolved to let

the commander and his captains get refreshments on shore, but told them

that their men were not to land until the over-lord of the town had been

consulted. Next morning, the Laird of Anstruther, accompanied by a goodly

number of the country gentlemen, entertained the general and captains in

his house, and allowed the soldiers, to the number of 260, to land.

Melville’s description of the latter is quaint, pithy, and expressive.

They were, he says, “for the maist part young bcrdles men, sillic,

trauchled, and houngercd !“ The Wodrow Society editor has in a footnote

translated this :—“ Young beardless men, feeble, dragging their limbs

after them with debility.” The rendering is woefully deficient, but that

is the fault of the English language, not of the editor. Melville’s advice

was like that of Elisha to the King of Israel, in Samaria, and, so, for a

day or two, “keall, pattagc, and flsche,” were given to them. Those who

had come to punish the heretics abjectly begged alms in the streets.

Meanwhile, they knew not that the remainder of the ficet had been lost,

but supposed that they had all reached home again in safety. One day,

however, Melville was in St Andrews, and there he got, in print, an

account of the wreck of the Galleons, the names of the principal men, and

how they were used in Ireland, the Highlands, Wales, and England. When he

told Jan Gomcs, the commander, how his friends and associates had been

treated, “he cryed out for greiff, burstcd and grat.” No wonder, for he

too though one of the cruel Spaniards and persecuting Papists, had a

kindly heart. He afterwards showed that he was truly grateful ; for, when

he found, on his return, that an Anstruthcr ship had been arrested at

Calais he rode to Court, greatly praised Scotland to his King took the

crew to his house, inquired for the Laird of Anstruthcr, the minister, and

his host, and sent them home with many commendations.

Parish. Swan in the

Ncw Statistical Account, Leighton, in his history of Fife, and Conolly,

in his Fifiana, all state that East Anstruther was disjoincd from the

parish of Kilrcnny in 1636. But they are certainly wrong with the date.

They were probably misled by the “friend to statistical enquiries,” who

drew up the old Statistical Account of the parish. From the Acts of

Parliament, it appears that, in 1641, our Sovereign Lord and Estates of

Parliamnent considered a petition, which had bccn given in to the General

Assembly, at Edinburgh, on the 21st of August 1639, at the instance of Sir

William Anstruther, and the bailies of East Anstruther, for themselves,

and in name of the remancnt inhabitents of the barons of Anstruther, and

burgh of Anstruthcr Easter. Im which petition it was mcntioned that the

burgh was populous and distant from the Kirk of Kilrenny “be the space of

ane myle of deepe evil way in the winter tymc, and other raynie tymes in

the ycre;“ and the rest of the people of the parish being quite enough for

the size of the church, the supplements had “ causit bigge ane kirk with

ane kirk— zaird” on the said Sir William’s heritage, within their burgh.

They intended to provide a stipend for the minister, if the Assembly

granted their desire by erecting the burgh into a separate parish, and by

ordaining the inhabitants to repair to the new kirk as their parish kirk

in all time coming, and to use the kirk-yard thereof for burial of their

dead. They were so reasonable, that they wished it to be provided and

declared that the dis-membering and erection per sc should not be

prejudicial to the kirk of Kilrenny, nor its minister and parishioners,

anent the implementing of the decreet of the Lords Commissioners of

Parliaments for surrenders and teinds, dated 29th June 1635, and of the

contract betwixt the minister of Kilrenny on the one part, and Sir

William Anstruther and the Council of East Anstruther on the other part,

dated 19th May 1636. The Assembly were pleased with the petition, and

referred it to this Parliament without prejudicing the rights of the

Presbytery and parishioners, and others having interest. The King, with

consent of the Estates, granted the petition on the 17th November 1641. A

protest was lodged, on behalf of the Kirk and patron of Kilrenny, that the

Act should not prejudice their rights; and on the same day the Kirk of

Anstruther protested against the ratification of the Kirk of Kilrenny.

The Parish Church is

said to have been built in 1634, and exactly 200 years afterwards it was

thoroughly repaired internally. It was then described in the New

Statistical Account as being, “probably, one of the most elegant country

churches anywhere to be seen !“ Now, it is dingy enough, and looking from

the pulpit it somewhat resembles a dismal cavern. There are two mural

monuments inside the church, one of which is in memory of Rear Admiral

William Black, a distinguished native and benefactor of the parish; and

the other, which is of a considerable age, bears the monogram M. I. D. The

stair-case in the steeple seems to have been the result of an

after-thought. Two doors on the south-west side of the church have been

built up. Over the smallest of these, the date 1634 is cut in modern

figures, and under the arch of the other, there are the dates 1675 and

1834. The tombstone of the Chalmers’ family stands at the south-east end

of the church, and the genial Tennant’s is near it. Colin Adam, the first

minister of the church, was translated from Kilrenny in 1641. He gave 100

merks towards “levying ane regiment of horse for the present service” in

1650, and two years afterwards the English soldiers challenged him for

praying for Charles the Second, and carried him as a prisoner to Edinburgh

for persisting to do so. At the Restoration of Charles, he declined to

conform to Episcopacy, and was confined to his parish, while some who had

truckled to the Usurper were advanced to place and power. The staunch old

man died in 1677. He was succeeded by Edward Thomsone, whose fate was more

tragic. “Being left a widower, he ‘became very sad and heavy,’ and on

Saturday, the 19th December 1686, he went to make a visit at night, and

stayed late. As he returned, the servant girl that bare his lanthorn

affirmed it shook as they passed a bridge, and that she saw something like

a black beast pass before him. After he returned, and had been a while in

bed, he rose early next morning and threw himself into the Dreel, and when

found he was dead.” His successor, William Moncrieff, “demitted

voluntarily in 1689, after disobeying the proclamation enjoining prayer

for their majesties, William and Mary and praying for King James.” The two

Nairnes, father and son, James and John, discharged the pastoral duties

for 78 years. Their monument is in the south-west wall of the church. The

one died in his 90th year, and the other in his 85th. Both were lairds of

Claremont, near St Andrews.

Trials and Troubles.—In

July 1641, East Anstruther gave £2511 Scots to the factors at Campvere,

as their part of the price of arms and ammunition sent home. This with the

interest was ordered to be repaid in August 1644, but the money does not

appear to have been refunded by Government. Like their neighbours at

Crail, they had borrowed it from Sir James Murray, and like them they

found him to be an exacting creditor. Much light is thrown on their

sufferings by three Acts of Parliament passed in their favour in 1649.

From the first of these we learn that they were still due Sir James the

principal sum of £2511, and £907 12s of interest. A small committee,

appointed to consider their supplication, found their loss “to be

extraordinarie great both in men and shiping ;“ that their burdens were

also great, and that these were partly contracted by building their new

church, and partly by paying a considerable part of the Kilrenny stipend,

as well as the whole of their own minister’s, without any help, they

having no burgh acres. The great burdens had caused many of the

inhabitants to desert the town, and that, of course, told all the more

against those who either could not or would not do the same. On the

suggestion of the committee, Parliament, on the 23d of February, ordained

that the monthly maintenance and excise of the town should, for 18

months, be applied to the payment of their debt; and recommended two of

the committee to speak to the University of St Andrews, that with their

consent a part of the excrescence of the rents of the Priory and

Bishopric of St Andrews might be appointed for paying one of the

stipends. But this Act was insufficient to relieve them. For Sir James

Murray, determined to have his pound of flesh, put them to the horn, which

rendered them unable to borrow money wherewith to repay him. The Bailies

and

Council again petitioned

Parliament. And, on the 29th of June, the Estates recommended the

Commissioners of the Treasury and Exchequer to grant them their own

escheits gratis, and ordered the Lords of Session to grant suspension

without caution or consignation; but the Bailies and Council were to

satisfy the debt with which they were charged in the former Act. In a few

days they had to present another supplication to Parliament, showing, that

besides all their former losses, there “is presentlie takin from them, by

ane pirot, neir the Iland of Maij, ane schip perteining to them, loadine

with corne, coming to them from the eist countrie, and ane vther vessell

coming from Noroway; lykas, the samyne pirot hes also takin tuo fisher

boatts, and forcit vther tuo to rune aground whairby they are lost.”

Indeed, the pirates, who always lay near the coast, had brought them to

such a condition that “they dare not goe out to tak ane fish for thair

intertainement, though the most pairt of them have not ane bite of meat

to put in thair mouthis, whill (i.e., until) first it be gottin out of the

sea.” These calamities were rendered more intolerable by the continual

quartering of troops upon them, and caused their neighbours daily to

desert the town. And so those who remained had either to starve or ask

“remeid” from Parliament. They had chosen the latter alternative, and now

pled that they might be relieved from quartering for 18 months, as they

had been from maintenance. Their desire was granted by the Estates on the

9th of July 1649. They had likewise sent a joint petition with Pittenweem

to Parliament that year, which was also favourably received by the Estates

on the 22d of June; and from which it appears that they were actually

selling their clothes and household plenishing for meal. Twenty years

later they had again to petition Parliament, and their circumstances now

appeared to be more desperate than ever. Through the execution of the law

against the persons of Magistrates for public debts, no one would accept

the office, and many disorders had arisen in consequence. The burgesses

and inhabitants, therefore, offered their humble supplication, in which

they stated that, before the late troubles, the burgh had 22 or 23 sail of

good ships, and many barques or small vessels; that the chief employment

by which the burgh subsisted was the Orkney and summer “bushing fishing,”

and the Lammas herring drave, which had altogether decayed; and, that they

had only 3 vessels now, the greatest of which did not exceed 20 or 24

last. Further, for their loyalty and affection to his Majesty, they were,

in 1651, beyond all places of the country, “totallie plundered by the last

usurpers, nothing immaginable that wes transportable or moveable (being)

left them,” and some of the inhabitants were killed at the same time. By

the insupportable burdens, many of the families were brought to ruin and

beggary, and the burgh was involved in debt to the amount of 15,000 or

16,000 merks. Besides their own minister’s stipend, they had still to pay

430 merks yearly to the minister of Kilrenny. To meet these debts, they

had no common good, except customs and anchorages, which did not amount to

400 merks, and that was not enough for maintaining even the harbour. A

great part of “the most considerable inhabitants” had removed to other

places, which was like to bring this poor burgh—which for 86 years had

borne all public burdens—to utter ruin; and, as there was not “a furr of

land within the paroch bot the meer precinct of the towne,” the parish

kirk would also decay altogether if some speedy remedy were not granted.

The poor inhabitants who remained, however, knew of a remedy, which they

believed would be effectual. Like Mr Gladstone, they prayed Parliament to

allow them to impose a duty on ardent liquors; but unlike him they were

successful. On the 1st of December 1669, the Lords of the Articles

recommended their petition; and on the 22d of August 1670, Parliament

empowered the Magistrates and Council to be elected, to impose on each

pint of Spanish, Rhynish, and Brandy wine, sold within the burgh, a duty

of 2s Scots; on each pint of aquavitae and French wine 1s; and on each

pint of ale or beer 2d. This was to endure for 7 years, and the duties

were to be employed in paying the town’s debts. Verily, the starving

inhabitants were not Good-Templars!

Fishing.—As there

was a dispute between the Abbot of Dryburgh and the Prior of May in 1225,

concerning the teind of the fish landed in the Dreel Burn, there must have

been fishing in the district for more than six centuries; but, like other

industries, it has had many ups and downs during that time. On the 22d of

March 1661, Parliament considered a supplication from East Anstruther and

Pittenweem, in the same terms as that from Crail and Kilrenny (see page

5), and similar liberty was granted. In both cases it was to endure until

the first of January 1662.

Writing in 1710, Sibbald

says :—“They have good magazines and cellars for trade, and are provided

with all accommodations for making and curing of herrings; which is the

staple commoditie of this town, and of all the towns in this east coast of

Fife. And this town sends about twenty-four boats to the fishing of

herring, formerly they sent yearly about thirty boats to the fishing of

herring at the Lewis.” Anstruther is now one of the 26 fishery districts

into which the coast of Scotland has been divided. In the newly published

Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland, it is stated that, “Anstruther is head of

all the fishery district between Leith and Montrose.” That work, however,

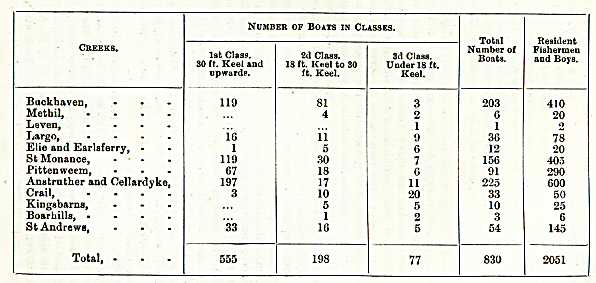

is singularly inaccurate regarding Anstruther. The First Annual Report of

the Fishery Board for Scotland was issued in 1883, and there the

boundaries are defined as only extending “from Buck-haven to south side of

Tay both inclusive.” The foregoing table, taken from that Report, shows

the number of boats and fishers in each of the fishing villages and creeks

of the district. From another table in the same Report it appears that

the first-class boats of this district have an aggregate tonnage of 9646

tons, the second-class 838 tons, and the third-class 179 tons the total

tonnage of the 830 boats being 10,663 tons. The number of fishermen and

boys employed that year was 3491, there were 46 fish-curers, 76 coopers,

and other persons connected with the industry were estimated at 2362,

bringing up the total number of persons employed to 5975. The value of the

boats was estimated at £66,960, the nets at £95,584, the lines at £14,132

— making a grand total of £176,676. To show the relative position of the

Anstruther district, a few more facts may be gleaned from the same table.

Only two of the other 25 districts surpass it in the number of boats,

viz., Buckie, which has 863, and Stornoway, which has 1091. But while the

tonnage of Buckie is 11,805 tons, that of Stornoway is only 7282—that is,

fully a third less than Anstruther. Only five of the 26 districts have a

tonnage of more than 7000 tons, and 15 of them are under 4000. In the

total value of boats, nets, and lines, Anstruther district stands first.

Next comes Buckie with £175,550, then Peterhead £117,536, Fraserburgh

£114,177, Wick £92,404, and Findhorn £77,774. Fifteen of the others are

under £50,000, and of these ten are under £30,000. In short, the number of

the boats in the Anstruther district is an eighteenth, the tonnage an

eleventh, and the value of boats, nets, and lines nearly an eighth, of the

whole in Scotland. To show the importance of this industry, it is enough

to mention that there is good reason for believing that about a seventh of

the entire population of Scotland is more or less dependent on the

fisheries.

Harbours.—The ports

of Pittenweem and Anstruther were mentioned seven centuries ago by William

the Lion. In those ancient times, the mouth of the Dreel Burn served as a

harbour for both Anstruthers. No doubt, Dr John Stuart says that the

dispute, between the canons of Dryburgh and the monks of May, in 1225,

respected the tithes of the ships and boats fishing in this burn. And Dr

J. F. S. Gordon, who takes the same view, makes merry over it in his

Monasticon. This river, he says, “is such a mighty Amazon that it is now

capable of floating a covey of ducks—the only fishers to be seen at the

present day looking after the tithes in the Dreel, for behoof of the monks

of May.” As Mr David Cook, however, has pointed out, it is not only

difficult to believe that ships and boats could have fished in the Dreel

even six centuries ago, or that the tithes of the fish caught there were

worth contending about; but the document in question bears that the

dispute turned on the mooring of the ships and boats, on the Kilrenny side

of the so-called river. The fish caught in the open sea would be landed

there. This also seems to be the opinion of the editor of the Dryburgh

Chartulary. In a charter, granted in 1544, reference is made to the ports

of Anstruther within the parish of Kilrenny, as well as to the new port of

Kilrenny. Little is now known about these several ports or havens. But, in

1 669, the harbour of East Anstruther was spoken of as the most useful and

necessary in the mouth of the firth, for all natives and strangers, and as

the only subsistence and safeguard of the burgh against the ocean. And,

in 1710, Sibbald said that it was the best harbour in Fife, except those

at Burntisland and Elie, and that the pier was very convenient for loading

and unloading ships. It is stated that, in 1710, Anstruther was changed

from a creek of the custom-house of Kirkcaldy into a port, a custom-house

being established here; that, in 1753, a new quay was built on the west

side, extending nearly as far as that on the east, to defray the expense

of which, Parliament sanctioned a tax of twopence Scots on every pint of

ale brewed or sold in the burgh; and that the tonnage, which, in 1768,

only amounted to 80 tons, rose before the end of the century to 1400.

Shipbuilding at that time was carried on to a considerable extent.

Government began to construct the Union Harbour, on the eastern side of

the other, in 1866. The task was an arduous .one in itself, and was

rendered more so by violent storms. It was not finished until 1877, and

the total cost exceeded £80,000. Yet, in a gale, the boats are not safe in

the outer harbour. The Chalmers’ Lighthouse on the end of the long pier

was inaugurated on the centenary of his birth. It, the safety-rail, and

the life-boat “Admiral Fitzroy,” were the gifts of Hannah Harvie. The 4th

verse of the 93d Psalm has most appropriately been inscribed on the

granite slab over the doorway of the Lighthouse.

Maggie Lauder’s House.—In

spite of the favourite song, written by Francis Semple of Beltrees 240

years ago, some people are incredulous enough to doubt whether there was

ever such a personage as “bonny Maggie Lauder.” It need hardly be said

that the folk of “Maggie Lauder’s toun” have no scruples on the subject.

They can still point out the “snug wee house in the East Green,” which

“shelter kindly lent her.” To them, Mr Conolly must have appeared

fastidious indeed, when he threw doubt on the identity of her dwelling.

What matters it though the house does not look so old? Is a precious

tradition to be ruthlessly sacrificed to propitiate the misgivings of a

few prying antiquaries? It will be long before they bring such renown to

the ancient town. Away with them! Professor Tennant, like a true born

native, knew better when he wrote his rollicking poem on Anster Fair, and

carried his heroine back to the days of King James the Fifth. Beltrees

made her say to Rob the Ranter—

“I’ve lived in Fife, baith

maid and wife,

These ten years and a quarter.”

But Tennant with more

gallantry speaks of her as—

“A young fair ]aay, wishful

of a mate ;“

and according to him—

“Rob is a Border laird of

good degree,

A many.acred, clever, jolly squire,

One born and shap’d to shine and make a figure,

And bless’d with supple limbs to jump with wondrous vigour.”

Unfortunately, the East

Green now belies its picturesque name and romantic traditions, having been

turned into a prosaic, narrow, long, low-lying street, connecting

Anstruther and Ceilardyke. But there, towards its eastern end, the house

can still be seen.

“In th’ East Green’s beat

house fair Maggie staid, Near where St Ayle’a small lodge in modern day

Admits to mystic rites her bousy masons gay.”

Those who are not satisfied

with such evidence must remain unconvinced, for no other can be produced.

Anster Loan, on

which the famous Anster Fair was annually held, is on the northern side of

the town near the St Andrews Road. Seventy years ago Tennant said that

although “at present its limits are contracted almost to the highway,” it

“must, in those days, have been of great extent.” In another of his notes,

he states that “Anster Lintseed Market (as it is called) is on the 11th of

April, or on one of the six days immediately succeeding.” In 1696, it was

changed by Parliament from the 1st of May to the 24th of June.

Town Hall. — The old

townhouse which stood in Shore Street was a very plain, common-place

building. It is believed to have been nearly three centuries old, and was

repaired in 1806. Latterly, the upper floor served as the council chamber

and common hall, while the under portion was used as a manure store! Now,

however, it has been swept away. The handsome and commodious new Town

Hall, which has been built near the church, is dated 1871.

The Market Cross,

which is a conspicuous object in Shore Street, bears the date 1677.

Dreel Castle, which

stood near the sea on the eastern side of the Dreel Burn, was long the

seat of the Anstruther family, the descendants of William de Candela, who

owned the lands of Anstruther in the days of David the First. It is said

that Henry, the son of this William, was the first to assume the name of

his lands. The castle, it is stated, was one of the old square massive

towers, with walls of enormous thickness, and which, in the olden times,

were almost impregnable. The name is still so far preserved by Castle

Street. Balfour, in his A nnals of Scotland, says that Charles the First,

in his visit to Fife, six weeks after his coronation at Scoone (1651),

stayed a night at Anstruther. And Lamont, in his Diary, states that, on

the 14th of February 1651, “he came alonge the coast by Levin, Largo,

Ellie, and lodged att the Laird of Ensters house all night.”

Alas! for the old castle,

its princely visitor is said to have been its ruin. For Conolly has

preserved the tradition, that, after enjoying the sumptous repast, Charles

was ungallant enough to exclaim :—“ Eh, what a fine supper I’ve gotten in

a craw’s nest !“ And that “the sensitive knight was so much stung by the

royal remark, and the loud laugh of the courtiers which followed it, that

he resolved to erect a new mansion more in accordance with the altered

state of the times.” Shortly after the Restoration, he therefore began to

build the house which was known as

Anstruther Place,

and which Sibbald briefly describes as “a stately house . . . overlooking

the town.” Conolly says that:- "The original contract for this house, made

with Alexander Nesbit, deacon of the masons in Edinburgh, provides that it

shall be 76 feet by 24 feet within the walls, and of four storey, and the

walls four feet thick. The hall and dining-room were on the second storey,

and the windows in the former were to be ‘as large and complete as those

in the hall of Kellie.’ There was a large rustic entry-gate on the west

side, ‘conform to the principal gate of Belcarres,’ and ‘sufficient square

docote of the quantity of Sir James Lumsdaines’, of Innergellie, his

docate.’ The price, including a stable, and a bake and a brew house, was

fixed at 2200 merks, and 16 bolls of oatmeal, besides the joiner work, for

which was paid 200 merks, 4 bolls oatmeal, 4 bolls pease, and 2 bolls bere

and the iron work, the payment of which was £200, and 2 bolls of here.”

This costly and extensive pile of buildings was only inhabited by the

proprietors for about a century, when they removed to Elie House. It was

afterwards occupied by the old servants of the family, but when the

present turnpike road was made in 1811, it was razed to the ground. The

Clydesdale Bank has been built close to its site.

Birthplace of Dr

Chalmers.—In Dr Hanna's voluminous Memoirs of Chalmers, remarkably

little is said about his birth, and nothing more definite about his

birthplace than that it was in Anstruther. The house, however, is still

pointed out; indeed, the precise room and veritable box-bed are shown, in

which the great ecclesiastical leader and philanthropist first saw the

light. On the south side of the High Street, a few doors east from the

National Bank, there is a narrow close which leads straight to the house.

Lately the dwelling had

become very dingy and somewhat dilapidated, but a few days ago (June 1885)

it was bought by Mr Fortune, chemist, for £80. Already he has repaired the

roof, and given the building a new face of cement. The whole house is to

be thoroughly renovated and fitted for a better class of tenants. With

praiseworthy consideration he is not to interfere with the special room

beyond cleaning it. The wooden pannelling and box-bed are to be left

intact. The house is two storeys in height, and has a large garret

besides, and capacious cellars underneath—the beams of the latter being of

good sound oak. Chalmers was one of a family of fourteen, and was born on

the 17th of March 1780. It seems that this house was not the usual

residence of his parents, that, in fact, they had oniy gone into it while

their own domicile was being repaired or altered. His father’s shop, which

was a little further west in the same street, but on the opposite side,

has been transformed into a post office; and, immediately to the west of

it, there is a rather ruinous range of buildings which was formerly the

thread manufactory of Chalmers and his brother-in-law. It has been

asserted that the refuse and dye from this manufactory drove the salmon

from the Dreel. Be that as it may, immediately behind these buildings

stands the house in which Thomas Chalmers spent his youthful years,. and

where his parents lived and died. There the active Bailie, who was

diligent in business and fervent in spirit, enjoyed his favourite authors,

James Hervey and John Newton. He was particularly fond of the once-famous

and widely-prized Theron and Aspasio. When the Doctor came to visit his

worthy parents in 1816, nothing brought back the old times more forcibly

to him than an Anstruther Sabbath. “In the spring of 1845, Dr Chalmers,”

says his biographer, “visited his native village. It almost looked as if

he came to take farewell, and as if that peculiarity of old age, which

sends it back to the days of childhood for its last earthly

reminiscences, had for a time and prematurely taken hold. of him. His

special object seemed to be to revive the recollections of his boyhood —

gathering Johnny Groats by the sea beach of the Billowness, and lilacs

from an ancient hedge, taking both away to be laid up in his repositories

at Edinburgh. Not a place or person familiar to him in earlier years was

left unvisited. On his way to the churchyard, he went up the very road

along which he had gone of old to the parish school. Slipping into a poor

looking dwelling by the way, he said to his companion, Dr Williamson, ‘I

would just like to see the place where Lizzy Geen’s water-bucket used to

stand ‘—the said water-bucket having been a favourite haunt of the

over-heated ballplayers, and Lizzy, a great favourite, for the free

access she allowed to it. He called on two contemporaries of his boyhood,

one of whom he had not seen for forty-five, the other for fifty-two years,

and took the most boyish delight in recognising how the ‘mould of

antiquity had gathered upon their ‘features,’ and in recounting stories of

his school-boy days. ‘James,’ said he to the oldest of the two, a tailor,

now upwards of eighty, who in those days had astonished the children, and

himself among the number, with displays of superior knowledge, ‘you were

the first man that ever gave me something like a correct notion of the

form of the earth. I knew that it was round, but I thought always that it

was round like a shilling till you told me that it was round like a

marble.’ ‘Well, John,’ said he to the other, whose face, like his own, had

suffered severely from small-pox in his child-hood, ‘you and I have had.

one advantage over folk with finer faces—theirs have been aye getting the

waur, but ours have been aye getting the better o’ the wear!’ The

dining-room of his grandfather’s house had a fire-place fitted up behind

with Dutch tiles adorned with various quaint devices, upon which he had

used to feast his eyes in boyish wonder and delight. These he now sought

out most diligently, but was grieved to find them all so blackened and

begrimed by the smoke of half a century, that not one of his old

wind-mills or burgomasters was visible.” Two years later he followed his

parents to the Better Land.

“The cry at midnight came,

He started up to hear;

A mortal arrow pierced his frame—

He fell, but felt no fear.”

Goodsir’s Birthplace.—John

Goodsir, the eminent anatomist was descended from a race of doctors. His

grandfather, John Goodsir of Largo, was “a tall, gaunt, wiry giant,” a

“medicine-man of a period and region that knew nothing of

brougham-equipped or gig-driving doctors ;“ he “rode his rounds on a

horse, chiefly remarkable for its stoical endurance of the spur, with a

pack of drugs and instruments attached to his saddle, and a lamp at his

knee.” His piety became as noted as his physic, for he occupied the

Baptist pulpit of Largo for twenty years. Three of his sons became

surgeons, one of whom, John, settled at Anstruther, and took up his abode

in the house immediately to the west of Melville’s manse, where his son

John was born in 1814. John the third gave early indications of his

predilection for anatomy. He and his brother Henry pursued their

investigations in the upper room of a small house, which forms a wing of

the main building. “In order that they might not be disturbed by idle, if

not inconvenient curiosity, the regular entrance was barricaded up, and

the room could only be reached by a trap-door from below. Long after the

house had passed into the possession of others, this apartment continued

to bear many a trace of the dissecting room. The ceiling, in particular,

was covered with drawings of skeletons and death’s heads, beneath one of

which the youthful anatomist had written, while in a moralising mood,

‘Behold our lot!”

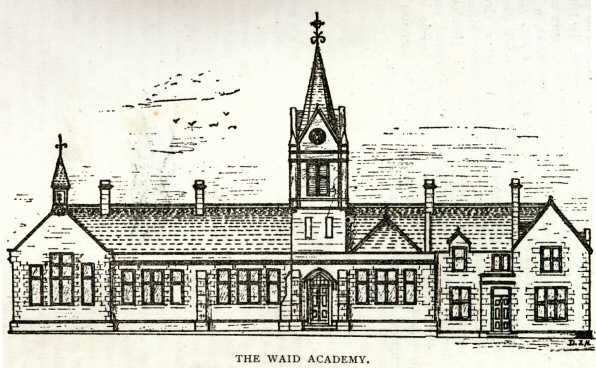

The Waid Academy is

just about to be built in the field immediately to the north of Adelaide

Lodge, and near the railway station. The cost will be over £3000. Its most

striking feature, as will be seen from the accompanying illustration, is

the tower and spire, which is to be 80 feet in height. There is to be a

large room of 58.5 feet by 22, and ether four, each of which will be 22.5

feet by 19.5 The entrance hall is under the tower.

The rector’s house also.

forms part of the building. Mr Henry of St Andrews is the successful

architect. Andrew Waid, a native of Anstruther, became a lieutenant in the

Royal Navy, and died in London in 1804. He disponed his whole property,

after paying certain annuities, to twelve trustees for the purpose of

erecting this academy, to educate, clothe, and maintain poor orphan boys

and seamen’s sons.

Population, Public

Institutions, &c.—The population from 1744 to 1831 varied from 900 to

1000. In 1881 it had risen to 1349. Besides the Parish Church, there are a

Free, U.P., Baptist, and E.U. churches; three banks, a post office, a

gas-work, and two hotels. The East of Fife Record is also published here;

while the Fife News, which devotes much space to the local intelligence,

has a large circulation in the district. There are many excellent villas

on the northern outskirts of the town, and Mr Henderson, builder, has

recently acquired a large plot of ground, on the side of the Crail road,

on which to erect ten double villas with bay windows. It is also proposed

to increase the amenities of the town by getting a public park.

The Beggar's Benison

by David Stevenson, Emeritus professor in the Department of Scottish

History at the University of St Andrews. ISBN: 1 86232 134 5

Two clubs, dedicated to proclaiming the joys of libertine sex, thrived in

mid and late eighteenth-century Scotland. The Beggar's Benison (1732),

starting from local roots in Fife, became large and sprawling, with

branches in Edinburgh, Glasgow - and St. Petersburg. As a toast 'The

Beggar's Benison' was drink at aristocratic dnners in London as a coded

reference to sex, and the Prince of Wales (later George IV) became a

member.

Click here to see pictures

of Anstruther