"I cuist my line in

Largo Bay, And fishes I caught nine;

There’s three to boil,

and three to fry,

And three to bait the line."

The

Parish of Largo is

bounded on the east by the parishes of Newburn and Kilconquhar, on

the north by that of Ceres, on the west by that of Scoonie, and on

the south by Largo Bay. From east to west, its greatest breadth is

four miles, and from north to south four and a half. It contains

7585½ acres, including 200 of fore-shore. There are four villages

in the parish, three of which are near the Forth, and one is far

inland, to wit, Kirkton of Largo, or Upper Largo, Lower Largo,

Lundin Mill, and Back-muir of Gilston. Mr Oliphant, in describing

it in the old Statistical Account, in 1791, says:- "To the

traveller, the south part of this parish must afford a picturesque

and delightful scene of elegant country-seats, skirted with well

laid out and thriving plantations, populous villages, surrounded

with fertile fields, hill and dale, wood and water..... In

improvements, it may be justly said that this parish has led the

way to all the neighbourhood." An open field was scarcely to be

met with. Drainage had not been neglected. Useless marshes and

deceitful bogs had been turned into fruitful fields. The brake and

roller were in common use. Instead of the old-fashioned plough,

drawn by six cattle and two horses, which had been the common

thing twenty or thirty years before, a light well contrived plough

had been introduced, which, though drawn by only two horses,

reined by the ploughman, did the work better and more quickly.

Hand and horse hoeing were practised. When the crop was gathered,

it was "preserved in the barn-yard from vermin, by being placed

upon pillars of stone, 2 feet high." And, to crown all, machines

for threshing had been introduced! But these, "from their very

complex construction," were apt to go wrong, the horses had "a

dead draught," and were "made giddy by the circular motion."

Turnips and cabbage were successfully raised. "The carrot, the

Swedish turnip, and root of scarcity"

had "not answered expectation." But it was supposed that the

Swedish turnip would become very useful when the proper mode of

cultivating it was ascertained. Great attention was paid to the

rearing of cattle, and, consequently, these had been

"distinguished for beauty and size even in the London market."

Horses were bred both for draught and saddle. Sheep were fed. And

every family had swine. Land had increased so much in value, that

what had been let at 16s and £1 per acre twenty years before drew

£2 and £2 10s. Wheat, barley, oats, beans, and sometimes potatoes,

were shipped for Leith and the West country, and salt to Dundee

and Perth. Wood and iron were imported from Norway. There were

three corn, two barley, and three lint mills, as well as two

salt-pans in the parish. The weaving of linen and checks were the

principal industries. Flax was imported, and much of it was

dressed and spun in the parish. Common labourers only received

from ninepence to a shilling per day, and, so, those who had

families could not "live sumptuously." Indeed, Mr Oliphant says

"Except at a birth or marriage, or some other festival, they do

not in general taste butcher-meat. Meagre broth, potatoes, cheese,

butter in small quantities, and a preparation of meal in different

forms, make up their constant fare." Yet, "all things considered,

it is astonishing to see man, wife and children, in their Sunday’s

clothes all are clean and neat, with faces expressive of

contentment." Notwithstanding the "spirit of schism" which

prevailed, the people were "honest, sober and industrious," but

"more forward to sympathise with their neighbour in distress, than

to rejoice with him in his prosperity." Such is the outline of the

picture of his flock drawn by the minister a century ago.

The

Name

of the parish was formerly written, Largach,

Largauch, Largath, and Largav.

Upper Largo,

or the Kirkton of Largo,

which, in the words of Chambers, is "a remarkably agreeable little

village," is situated near the western boundary of the parish, and

three quarters of a mile from the sea. Its most prominent

buildings are the Parish Church, the Free Church, and Wood’s

Hospital. It also contains a comfortable inn, a gas-work, a post

and telegraph office, a good schoolhouse near the new cemetery,

and a branch of the National Bank. In 1837 the population was 413,

and in 1881 it was 362.

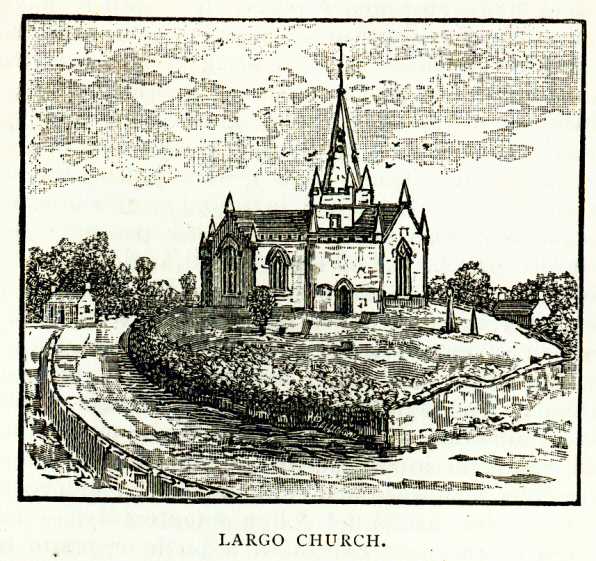

The Parish Church,

according to the New Statistical

Account, "was built in 1817 and in

1826, there was taken into the new building, an aisle belonging to

the old, by which the spire is supported, bearing date 1623. It

affords accomodation for upwards of 800." On one of the inner

walls there is a slab, which records, in Latin, that:- "This

church was first erected about the year 1300, in the reign of

Robert the Bruce, enlarged about the year 1400, ornamented with a

spire in 1623, again enlarged about 1688, and finally enlarged and

decorated in the year 1817." The inscription also preserves the

names of the heritors, minister, and architect, who rendered

themselves famous by the operations of 1817. As will yet be shown,

the church was first erected long before the year 1300. The

chancel and steeple are all that have been spared of the old

building; but even these seem to be comparatively modern. The

spire is dated 1628; and the chancel, which has been barbarously

plastered both outside and inside, has a panel, over the window,

bearing the motto, "Fear God," the date 1623, and the initials "P.

B.," while the arms are wasted away. The bell is dated 1636; but

it is worth no one’s pains to climb the steeple, as an outlook can

only be had through a small aperture. So determined have the

renovators been to hide the old work that a ceiling has been

inserted under the vaulted roof of the chancel; but while they

could spare funds for this, they economised their cash by putting

in wooden mullions ! This is the building which in Chambers’

Gazetteer of Scotland is described as "an ancient Gothic

fabric, with a spire rising from the middle!" The writer must have

gazed at it from a distance, for, though it is a pretty, neat

erection, and picturesquely situated, a glance at the masonry

shows that it is modern. There are few, if any, stones of interest

in the burying-ground; but that is more than made up by the great

number of mural marble monuments in the church. Among others

commemorated, are General and Admiral Durham, their father and

mother, their nephew, Thomas Calderwood Durham, and their niece,

Lilias Calderwood Durham, "the last of her race." There is also a

tablet in memory of Sir John Leslie, the distinguished

mathematician and Professor of Natural History, who was born in

Largo in 1766, and died at Coates, in Newburn parish, in 1832.

Another native, James Kettle, who lived to the good old age of 92,

and left £600 to the care of the Kirk-Session, is likewise

commemorated; and so are several other prominent men more or less

connected with the parish. While these stones are conspicuously

displayed on the walls, the monument of Sir Andrew Wood’s

descendants is allowed to lie ingloriously in the floor under two

pews! The old church was granted to the nuns of North Berwick hy

Duncan, Earl of Fife, and Earl Malcolm, his son, confirmed the

grant. William the Lion, in confirming their grants to these nuns,

specially mentions the Church of Largach. It was dedicated by

Bishop Bern-ham on the 16th Kal. of August 1243. Alexander Wod was

vicar here immediately before the Reformation. Reference has

already been made to him, and one of his illegitimate daughters,

on page 43. On the 10th of March 1559, a marriage was contracted

betwixt Alexander Carrik, "ane honorabill man," and Alisone Yod,

"dochter naturall" to "Maister Alexander Vod, vicar of Largow." At

the "handfasting," Carrik, his brother, and the vicar were

present, and signed a contract of the marriage, which was to be

solemnised between that date and the midsummer following. The

vicar delivered £20 at the handfasting, £40 was to be forthcoming

at the marriage, and another £40 within a year and a day after the

marriage. On the 13th of March, Jhone Spens, a burgess of North

Berwick, became surety and debtor for the £80 to Carrik. Of that

sum £30 was to be given by Dame Margaret Hume, Prioress of North

Berwick, and the remaining £50 by Wod. The Prioress and the vicar

bound themselves to relieve Spens. The shameless profligacy of

such men did much to ripen public opinion as to the necessity of

reformation. Those who wish to see the form of handfasting fuller

than it is in the above summary will find it in the Carte

Momalium de North-berwic. In 1597, Parliament dissolved the

kirks of Largo and Kilconquhar from the Abbey of North Berwick.

John Auchinleck was minister here from 1592 to 1619, and was

succeeded by his son Andrew in the following year, who was

translated to Dundee in 1642. James Fairlie, formerly Bishop of

Argyll, was thereafter presented, but was not received. This

unlucky wight was consecrated as a Bishop only two days before the

tumult about the liturgy, which led to the entire overthrow of the

Hierarchy. James Makgill was ordained at Largo in 1644. Lamont

relates several curious incidents that happened during Makgill’s

incumbency. The Commission of the Kirk appointed a fast to be kept

through the Kingdom, immediately before the coronation of Charles

the Second. This fast was observed at Largo on the 22d and 26th of

December 1650. On the second day the minister read the causes of

the fast, which were the sins of the King and his father’s house;

and the Earl of Lauderdale publicly acknowledged the sinfulness

and unlawfulness of the Engagement, his sorrow and remorse for

having acceded to it, and his resolution to beware of such courses

in future. Makgill then read the Solemn League and Covenant, and

Lauderdale holding up his hand sware it. The Kirk-Session gave him

a certificate bearing that they were well satisfied with his

repentance. Little did they know the man they had to deal with! In

1662, Parliament ordained that all persons in public trust should

take a Declaration, in which it was affirmed, inter alia,

that the Solemn League and Covenant was an unlawful oath, imposed

and taken against the fundamental laws and liberties. Sir George

Mackenzie, in his Memoirs of the Afairs of Scotland, says,

that the great design of this Declaration was to incapacitate

Crawfurd from being Treasurer, and Lauderdale from being

Secretary; but that "Lauderdale laugh’d at this contrivance, and

told them he would sign a cartfull of such oaths before he would

lose his place." Dr Burns, in his edition of Wodrow’s History,

expresses the opinion that Lauderdale "never forgot the

supposed indignity" that was put on him by the Covenanters in

Largo Church; and that it was only policy which prevented him from

coming out in his true character, as a persecutor, immediately

after the Restoration. Such a wretch could certainly never look

back with complacency on the Largo episode; and, in all

probability, he would not have humbled himself that day, if policy

had not been at the helm. Lamont describes a scene of a very

different kind which occurred in Largo Church in July 1652.

Makgill had finished his sermon and pronounced the blessing; but

before he could leave the pulpit two corporals of the English

regiment, which was lying at Largo and Leven, challenged him

because he had prayed for the prisoners in England—of whom

Lauderdale was one—as sufferers for righteousness sake. If he had

not been courageous, he would not have made such a reference in

his prayer in their presence. A few days previously, they had

quartered some of their men on him and Moncrieff of Scoonie,

although ministers in Fife had never been quartered on before. And

some of the soldiers, when they went to Largo church, "did sitt

ordinarlie (for contempt) in the stoole of repentance!" A year

later, the Presbytery of St Andrews met in the church of Largo,

and ordained that Thomas Wilson, the schoolmaster, should be

removed at the following Martinmas, "for profainlie taking the

name of the divill in his mouth twyse," for tippling, and

taunting, and not praying regularly every morning and evening in

the school. Wilson afterwards stood up in front of the pulpit,

while the preacher publicly rehearsed his faults, and then the

delinquent confessed on his knees that God was righteous, and

desired the people to pray for him. He seems to have been reponed,

for Lamont afterwards mentions him as schoolmaster, and says that

he was in -terred "betwixt his two wives," at Largo kirk, in 1670.

Makgill was one of those who would not conform to Episcopacy at

the Restoration, and who suffered in consequence. In April 1664,

Archbishop Sharp pronounced the sentence of suspension against him

and other six of his brethren, but their preaching was not stopped

at that time. Thirteen days afterwards, the High Commission

confined him to his parish, and for bade him to celebrate the

communion. In the following January, the sentence of suspension

was intimated to him by a messenger-at-arms, and in April 1665 he

was deposed. These incidents are recorded in the Life of Robert

Blair. Lamont tells how the patron would not present a

successor, and how, after six months had elapsed, Sharp presented

John Affleck or Auchinleck, whose father and grandfather had

ministered here before him. Only one of the heritors and three of

the elders gave him the right hand of fellowship, at his entry;

and, when, nearly two years later, he ventured to celebrate the

communion, the people, though earnestly invited, were so unwilling

to take part that there were only six tables instead of the ten or

eleven which had been usual in his predecessor’s time. It is a

long lane which has no turning. Like the other curates, he was

rabbled in 1689, and the same year he was deprived by the Privy

Council. In a rare tract entitled The Scots Episcopal

Innocence, printed in 1694, there is this brief entry :—August

29, 1689. "Mr John Auchin fleck, Minister at Largo; for not

reading and not praying, and praying for the late King. Present;

acknowledges the not reading and not praying. Deprived." Makgill

returned to his charge at this time, but died next year. He was

succeeded by William Moncrieff in 1691, who died in 1723. Fraser

tells, in his Life of Ralph Erskine, that he found, in one of the

note-books of that famous divine, an elegy on Moncrieff extending

to nearly 180 lines. Here is a specimen setting forth what he

thought of him :—

"This preacher showed himself

what few can do,

A Barnabus and Boanerges too,

A son of thunder, with alarming noise,

A son of comfort, with a charming voice.

Hence many came from distant parts, and saw

Sinai and Zion both, at Largo Law."

Moncrieff was succeeded by John Ferrier, whose

father was one of the magistrates of St Andrews. He occupied the

pulpit of Largo from 1724 to 1766, when he died. His son Robert

was ordained as assistant and successor to him in 1764, but having

adopted the principles of Independency, he resigned his charge in

1768, and, with Smith of Newburn, helped to form the congregation

at Balchristie. Robert Brown, who was ordained here in 1821,

joined the Free Church in 1843, and lived until a few years ago.

This venerable man, whose memory is fragrant, wrote the New

Statistical Account of the parish.

Wood’s Hospital is a handsome building,

designed by James Leslie, civil engineer, fully fifty years ago,

and erected at a cost of £2000. "It is fitted up for sixteen

inmates, each having a sitting and a sleeping apartment. In the

centre is a large hall, where they are convened to prayers morning

and evening; above which is a room for the meetings of the

patrons." At present, there are only eight inmates, and they are

all males. They are allowed to work for themselves, and each

receives thirty-five shillings every month, besides a share of the

garden. The hall, in which they meet for prayers, is the

entrance-hall of the building, and the floor is of pavement. In

the patrons’ room, which is immediately overhead, there is a very

small library. The governor acts as chaplain, and also discharges

the duties of church-officer. The previous hospital was built by

Robert Mill, "measter mason" in Edinburgh. The work began in April

1665, and about the end of the year, "the rooffe was put on this

buelding, and sclaitted and glased. It consisted of thrie roofs

one to the east, one to the north, and one to the west. The entrie

of it looked to the south." There were "24 divers rowrnes, with a

publicke hall; in each rowme ther was a bed and a closett and a

lowme, being all fyre rowmes, with a large garden; a stone bridge

for itts entrie; a howse besyde for the gardiner, two story high.

Abowt 6 persons were entered to stay at the said hospitall about

Candelmisse 1667." John Wood, who was a descendant of the famous

Sir Andrew Wood of Largo, was a courtier, and, though a wealthy

man, died in straitened circumstances in London, as the money he

had with him ran short. He was buried in Largo church, in July

1661. On the 7th of July 1659, he executed a deed of

mortification, to build and uphold an hospital in this parish, and

to maintain therein, "threttein poore indigent and infirme

persones." This mortification was ratified by Parliament in 1661.

If tradition is correct, when he returned to the neighbourhood

after an absence of fifty-five years, he wished to see his

relative, the laird of Grange; but that selfish man, imagining

that he might require or wish pecuniary help, declined to meet

him, which so enraged the stranger that he resolved to devote his

fortune to the erection and endowment of the school at Drumeldrie,

and the hospital at Largo. In 1657, he built the wall round the

churchyard.

Largo House, which is immediately to the

westward of the Kirkton, was built in 1750; but one of the round

towers of the earlier building is still to be seen. It has been

alleged that at one time it was a jointure-house of the Queens of

Scotland; but I have seen nothing to substantiate that statement.

There can be no doubt, however, that the old house was built by

Sir Andrew Wood, the famous and first great sea-captain of

Scotland. Tytler quotes from a charter under the great seal, dated

the 8th of March 1482, to show that James the Third granted to

Andrew Wood, his own intimate servant and a citizen of Leith, the

lands and village of Largo, in consideration of his gratuitous and

faithful services, freely undertaken both by sea and land, in

peace and war, within and without the kingdom, and conspicuously

against his English enemies, at the risk of serious personal

danger. Soon afterwards, Wood set to work and built certain houses

and a fortalice on his lands of Largo, in order to resist and

expel the pirates, who invaded the kingdom; and, with a grim sense

of the eternal fitness of things, he made his English captives act

as masons. These facts are set forth in another charter under the

great seal, dated the 18th of May 1491, which Tytler also cites,

and in which James the Fourth gives Wood further liberty to build

a castle at Largo with iron gates. By far the best account of

Wood’s exploits is to be found in Pitscottie’s History of

Scotland. With much simplicity and graphic force, he tells how

Wood bearded the nobles after the death of the unfortunate James

the Third, in 1488, how the two lordly hostages narrowly escaped

hanging at the yard-arm, because he was longer detained than his

men expected, and how Captain Barton informed the Council, "that

there were not ten ships in Scotland would give Captain Wood’s two

ships the combat, for he was so well practised in war, and had

such artillery and men, that it was hard dealing with him by sea

or land." Wood was soon reconciled to. James the Fourth, and

served him as faithfully as he had done his father. It was in or

about 1490 that five piratical vessels entered the Clyde, and

chased one of the King’s ships to Dumbarton. By special request,

Wood set out in search of them, and after a hard fight brought

them all prisoners to Leith. The English could ill brook such a

defeat, but no one cared to tackle the Scottish sea-lion. At

length, Steven Bull, with "three great ships, well man-steid, well

victualled and well artilleried," took in hand to bring Wood to

the English King, either dead or alive. Confident of attaining his

purpose, he sailed for the Forth, and lay behind the May, to watch

for Sir Andrew as he returned from Flanders. Early on a summer

morning two ships were perceived coming round St Abb’s Head. Bull

immediately sent aloft some Scottish fishermen, whom he had

captured, to see if it was Sir Andrew. At first they pretended

ignorance, but, on the promise of their freedom, they acknowledged

that the two vessels were Wood’s. The result can best be told in

Pitscottie’s own words:- "Then the Captain was blyth, and caused

pierce the wine, and drank about to all his shippers and captains

that were under him, praying them to take courage, for their

enemies were at hand; for the which cause he caused order his

ships in the fier of war, and set his quarter-masters and

captains, every man in his own room; syne caused, his gunners to

charge their artillery, and put all in order and left nothing

undone pertaining unto a good captain. On the other side, Sir

Andrew Wood came peartly forward, knowing no impediment of enemies

to be in his geat; till at the last, he perceived thir three ships

under sail, and coming fast to them in fier of war. Then Sir

Andrew Wood, seeing this, exhorted his men to battle, beseeking

them to take courage against their enemies of England, who had

sworn and made their vows, that they should make us prisoners to

the King of England; but, will God, they shall fail of their

purpose. Therefore set yourselves in order, every man in his own

room. Let the gunners charge their artillery; and the cors-bows

make them ready, with the lyme-pots and fire-balls in our tops,

and two-handed swords in your fore-rooms; and let every man be

stout and diligent for his own part, and for the honour of this

realm. And thereto he caused fill the wine, and every man drank to

other. By this the sun began to rise, and shined bright upon the

sails; so the English-men appeared very awfully in the sight of

the Scots, by reason their ships were very great and strong, and

well furnished with greater artillery; yet, notwithstanding, the

Scots afeared nothing, but cast them to windward of the

Englishmen; who, seeing that, shot a great canon or two at the

Scots, thinking they should have stricken sails at their boast.

But the Scottish-men, nothing affeared therewith, came swiftly a

windward upon Captain Steven Bull, and clapt together from hand,

and fought there from the sun-rising while the sun go to, in the

long summer-day; while all the men and women, that dwelt near the

coast, came and beheld their fighting. The night sundred them,

that they were fain to depart from other. While, on the morn, that

the day began to break fair, and their trumpets to blow on every

side, and made them quickly to battle; who clapt together, and

fought so cruelly, that neither the shippers nor mariners took

heed of their ships; but fighting still, while an ebb tide and

south-wind bure them to Inchcap, foreanents the mouth of Tay. The

Scottish-men, seeing this, took courage and hardiment, that they

doubled their strokes upon the English-men; and there took Steven

Bull, and his three ships, and had them up to the town of Dundee."

The King was greatly pleased and richly rewarded Sir Andrew, and

chivalrously sent back Bull and his men as a present to the

English King, with the message that if any of his captains should

in future disturb his people in Scottish waters they would not be

so well treated. Sir Andrew never gave up his sailor ideas, and

the canal can still be traced in which tradition says he was rowed

to the parish church. Long may his memory be cherished as the

founder of the Scottish navy, and as one of the boldest and truest

sons of a heroic nation. Through course of time the estate of

Largo passed into another family, and in 1662, according to

Lamont, Sir Alexander Durham, the Lord Lyon, bought it from Gibson

of Dune, for about 85,000 merks. He died unmarried, next year, and

left it to his nephew Francis, the son of his celebrated brother,

the Rev. James Durham of Glasgow. Francis was succeeded in the

estate, in 1667, by his brother, who was the grandfather of that

James Durham, who married Anne, daughter of Thomas Calderwood of

Polton and Margaret Steuart. [Margaret was the grand-daughter of

Sir James Steuart, Lord-Advocate after the Revolution, and the

authoress of the shrewd and fascinating Letters and Journals,

which were first published in the Coltness Collections, in 1842,

and re-printed by Lieutenant-Colonel Fergusson in 1884.] They had

three sons, who were distinguished for their bravery, to wit,

James, Thomas, and Philip. James was born in 1754, and entered the

army when he was only fifteen. "In 1794 he was appointed Colonel

of the Fifeshire regiment of Fencibles, which he had raised, and

immediately obtained the rank of Brigadier-General. He served in

the Irish rebellion;" and had "for some years the command of the

Eastern District of Scotland. In 1830 he attained the rank of

General in the army." For many years before his death he resided

almost constantly at Largo House. He was "kind, neighbourly, and

humane." His constitution was unbroken, until a few days before

his death, although he was 86. He succeeded to the estate at his

father’s death, in 1808, and at his death in 1840 it passed into

the possession of his nephew Thomas, the son of Lieutenant-Colonel

Thomas Durham, who had died in 1815. Two years after the General’s

death, his brother Philip succeeded to the estate of Largo. "He

was born in 1763, and having entered the navy in 1777, was acting

signal-officer in the Royal George when she foundered at Spithead

in 1782, a catastrophe which only two of her officers survived."

He was appointed Rear-Admiral in 1810, Vice-Admiral in 1819,

Admiral in 1830, and Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth in 1836. "An

almost uninterrupted course of professional employment, and a not

less remarkable series of victories, fell to his share, from the

13th February 1793—when, as commander of the Spitfire, he took the

first tricolor flag that was struck to the British ensign, within

two days after hostilities had been declared—until, by a singular

coincidence, the last French colours at the close of the long war,

were hauled down in Guadaloupe, at his summons on the 10th of

August 1815." This worthy successor to Sir Andrew Wood died in

1845. The estate was sold, in 1868, to Mr Johnstone, and at that

time the old sculptured stone, which stood on the lawn, and the

cannon, which had belonged to the Royal George, were both removed.

There are still some very old fruit trees in the orchard.

Lower Largo stretches along the coast

for fully halfa-mile. The western portion is known as Drummochie,

and the eastern extremity bears the name of Temple. A winding walk

called the Serpentine connects Temple with the Kirkton, which is

half-a-mile due north. If Upper Largo has the advantage of

containing the Parish Church, the Free Church, and Wood’s

Hospital; Lower Largo can boast that it is nearer the waves, is

the birth-place of Alexander Selkirk, and possesses the Harbour,

the U. P. Church, and two Baptist Churches, both of the latter

being very near the water. Spence Oliphant, in the old

Statistical Account, says that "since the demission of Mr

Ferrier, who, in conjunction with a Mr Smith, minister at Newburn,

formed a sect of Independents, a spirit of schism has prevailed in

this and all the adjacent parishes." At that time fully a third of

the population of the parish were "Separatists," as he called

them. When Mr Brown prepared the New Account, in 1837, the

proportion of Dissenters was about the same; but six years later

he headed the Free Church movement in the parish, and so increased

the Dissenters still more. What is now the U. P. congregation was

formed in connection with the Relief Church. The "spirit of

schism," of which Mr Oliphant complains, may have prevailed; but

the immediate cause of the setting up of this congregation was the

appointment of Oliphant’s predecessor—David Burn—as Ferrier’s

successor in the Parish Church in 1769. When Burn knew that there

was opposition to him, he declined the call; but the patron, the

Laird of Largo, nothing daunted, issued another presentation to

him, which he accepted. "The people," says Mackelvie, in his

Annals and Statistics, "were not so willing to yield to the

patron’s wishes as the ministry, and a number of them carried

their non-compliance so far as to withdraw from the Established

Church, and cast in their lot among the Dissenters. In 1770, they

applied for and obtained supply of sermon from the Relief

Presbytery of Edinburgh. The patron was generous enough to grant

them a site for a place of worship. On this site they began to

build the proposed edifice. But being very limited alike in number

and pecuniary resources, they could not readily command the

co-operation they required. Nothing disheartened, they at length

set to work. Men, women, and children, were alike zealous, and

when the masons towards the end of their day’s labour left off

their work for want of material, they were often surprised next

morning to find an abundant supply—the men with barrows, the women

with their aprons, and children with creels, having procured it

for them over night from the beach, which skirts the village. The

congregation met in the open air till the church was completed. It

cost, exclusive of free carriages, the modest sum of £18 4s." The

new church, which is a very neat building, is seated for 400, and

cost £1200. It bears, under the initials of the esteemed pastor,

the date 1871. John Goodsir, who was "a physician by profession,

and a pastor by principle," preached to the Baptists of Largo for

twenty years. He was grandfather of the famous Professor Goodsir

(see Part I., p. 64). The population of Lower Largo, in 1837, was

567, and it has not increased greatly since.

Harbour and Fishing.—The Harbour is a

very small miserable affair, at the mouth of the Kiel Burn, near

the imposing railway bridge. The fishing has had many ups and

downs. Lamont complains that in 1657, 1658, 1662, and 1663, there

were few or no herring caught on the Fife side, and not many at

Dunbar. Some thought there had not been the like for a century

before, and "beganne to feare ther sould be no dreve hireafter."

According to Sibbald, in 1710, there were "ordinarily three

fishing boats with five men in each, and in the herring season,

they have four boats with seven men in each." Eighty-one years

later, Oliphaut wrote:- "About ten years ago, fish abounded on

this coast, particularly haddock, of a very delicate kind. But

since that period, fish of every kind have become scarce, insomuch

that there is not a haddock in the bay. All that remain, are a few

small cod, podlies, and flounders. The fishermen have also

disappeared, who, 20 years ago, constituted the chief part of the

inhabitants of Largo and Drumochy. At present there is not a

fisherman in Largo, and only 1 in Drumochy, who fishes in summer,

and catches rabbits in winter." The only fishery to which Mr Brown

refers in 1837 is the salmon stake-net fishery, which had been

commenced a few years before. In 1883, there were 36 boats, manned

by 78 men and boys. The comparative position of the Largo

fishermen is shown by the table on Part I., page 56. While these

pages are passing through the press (April 1886), a gloom is

hanging over the place through the loss of the "Brothers." This

boat was last seen on the 30th of March, about 50 miles east of

the May. She had a splendid crew, and had weathered many a storm.

It is believed that she was swamped by a heavy sea, while the crew

were "hauling their lines," and the hatches off. One of the men

leaves a widow and a family of ten, while his two sons, who were

drowned with him, respectively leave a widow and three children,

and a widow and two. The skipper leaves a widow and four children.

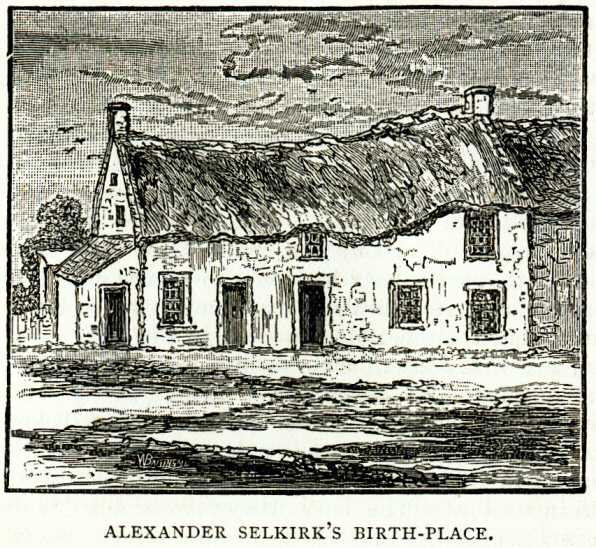

Alexander Selkirk.—Two centuries ago,

there was a prosperous shoemaker and tanner in Lower Largo, named

John Selcraig. His seventh son, Alexander, who was born in 1676,

proved a wild, restless youth. He was only thirteen when John

Auchinleck, the Episcopal incumbent of Largo, was rabbled by "a

great mob armed with staves and bludgeons."

It would have mattered little, to one of his

age and disposition, whether the obnoxious minister was

Presbyterian or Prelatic. Such an opportunity for furious fun

would have been irresistible, even although his eldest brother had

not been ring-leader, and accordingly he took part. Six years

later, he was summoned before the Kirk-Session for misbehaving in

the church; but, instead of appearing, he went "away to the seas."

His disposition seems to have remained unchanged, for in another

six years, to wit, in 1701, when he was again at home, a strong

young man of five-and-twenty, he raised a tumult in his father’s

house. His younger brother Andrew, who was of weak intellect, had

brought in a can of salt water, and laughed at him when he took a

drink of it by mistake. Alexander was so enraged at being laughed

at, that he struck him twice with a staff. Andrew cried for his

eldest brother, John; but, before he could appear on the scene,

Alexander tried to get into the upper room, where he had a pistol,

and was only prevented by his father sitting down on the floor

with his back to the door. On seeing John, he cast off his coat

and challenged him to a combat of "dry neifs." The father then

rushed between his sons to separate them; but the young sailor

seized them both and bore down his brother’s head. It was good for

this brother that he had a wife. She now came into the room, and

at once set to work to wrest Alexander’s hands from the head and

breast of her husband, who gladly escaped from the house, as soon

as his better half managed to release him. For this outbreak, he

was dealt with by the Session, and publicly rebuked before the

congregation. Soon after this he went back to sea, and became

sailing master of the Cinque Ports, of which Charles Pickering was

captain. The consort ship—the St George—was commanded by William

Dampier, who was the originator of the privateering expedition to

the South Seas, for which these ships had been fitted out. Dampier

was full of brilliant designs, but was extremely irritable and

vacillating. Pickering having died, Lieutenant Stradling was

appointed as his successor. Hitherto, the venture had been most

unfortunate, and discontent and wrangling broke out among the

crews. Selkirk—for he altered his name to that form—who had no

confidence in Stradling, had a remarkable dream "in which he was

forewarned of the total failure of the expedition and shipwreck of

the Cinque Ports." He accordingly made up his mind to leave the

vessel on the first favourable opportunity. Having reached Juan

Fernandez, two or three mouths after Pickering’s death, they

refitted their ships, and, while so engaged, "a violent quarrel

broke out between Captain Stradling and his crew." The men were so

discontented that forty-two out of the sixty resolved not to

return on board; but, wearying of the island, Dampier managed to

reconcile them to their captain. A French ship having come in

sight, the two privatcers set off in such hot pursuit that a few

of their men were left behind. The Cinque Ports returned for them;

but finding two French ships, of thirty-six guns each, at anchor,

Stradling sailed for Peru, and Dampier did the same, leaving the

men meantime to their fate. After adventures of many kinds, there

was such a quarrel that the two ships parted company. The Cinque

Ports cruised for several months along the shores of Mexico, and

during this period Stradling and Selkirk differed so much, that

the latter determined to leave. Want of provisions, and the state

of the vessel, forced them to return to Juan Fernandez, where they

found two of the men they had left six months before. The

relations between the captain and the sailing-master getting more

strained than ever, Selkirk was landed, with his chest, a few

books among which was a Bible, a gun, a kettle, an axe, and some

other necessaries, just before the ship got under weigh. The sound

of the oars as the boat moved away caused him to realise the

horror of being left alone, perhaps, for life. He rushed into the

water, and besought them to return, but Stradling was inexorable.

At first, Selkirk was so dejected that he only ate when forced by

the pangs of hunger, but by degrees he became reconciled to his

lot. It was eighteen months before he could absent himself for a

whole day from the beach, where he watched for a friendly sail. He

built two huts—one of which he used as a kitchen—and was able to

keep himself in food and clothes by his fleetness and ingenuity.

The island, which is eighteen miles in length and six in breadth,

is remarkably beautiful, and in those days it abounded with goats,

which he ran down and caught. With his knife and a nail he shaped

and sewed the goat-skins into garments. Seals and shell-fish

varied his table, and the cabbage-palm served as a substitute for

bread. Rats were so plentiful that he had to tame some wild cats

to protect him during his sleep. He taught his tame goats and cats

to dance, and "often afterwards declared, that he never danced

with a lighter heart or greater spirit any where to the best of

music, than he did to the sound of his own voice with his dumb

companions." His early training and his father’s godly example

came back on him, and much of his time was spent in devotion. With

tears in his eyes, he afterwards said, that "he was a better

Christian while in his solitude than ever he was before, and

feared he would ever be again." He remained monarch of all he

surveyed for four years and four months, when, curiously enough,

he was relieved by another privateering expedition, of which

Dampier was also the projector, but not the commander. On the 31st

of January 1709, the Duke and Duchess came in sight of Juan

Fernandez, and a party landed next day. They were as surprised to

see him as he was pleased to see them. He caught goats for them

which their swiftest runners and a bull-dog could not overtake.

Salt and spirits he did not relish, owing to his long abstinence

from them, and shoes caused his feet to swell. He soon became a

favourite, and got the command of their second prize, which was

fitted up as a privateer, and named the Increase. Captain Rogers

seems to have been a model bucaneer, as, on one occasion, it is

specially mentioned, that before attacking a ship, the crew went

to prayers: and he was so tolerant, in his "floating

common-wealth," that while he used the Church of England service

on the quarter-deck, the Papists had mass in the great cabin

below—being, as he said, the low church-men in this case.

It was not until October 1711 that Selkirk landed in England. The

account of his adventures excited great interest in London. There

was still "a strong but cheerful seriousness in his look, and a

certain disregard to the ordinary things around him, as if he had

been sunk in thought;" and he "frequently bewailed his return to

the world, which could not, as he said, with all its enjoyments,

restore to him the tranquillity of his solitude." After getting

his share of the prize-money he came back to Largo early next

spring, and arrived on a Sabbath after his relatives had all gone

to church. He went after them, and, ere the service was ended, his

mother—moved by the unerring maternal instinct—recognised him, and

with a cry of joy rushed to his arms. They immediately left the

church. He stayed for some time in the old village, and

constructed a cave in his father’s garden, through which the

railway now runs. He loved to wander alone in Keil’s Den, and to

take solitary boating excursions, and seemed to return with

reluctance to the haunts of men. He should not have left his

island home. In vain his friends tried to cheer him. But, alas!

in Keil’s Den, he met a lonely lassie herding her father’s

oniy cow; and her solitary occupation, and innocent looks, made

such an impression on him, that he at last resolved to marry her.

Afraid of the jests of his friends, they eloped, and he never was

seen again in Largo. Like most other wives, Sophia Bruce made a

great difference on her husband, and when Sir Richard Steele met

him in the streets of London he did not know him. Copies of the

Power of Attorney and the Will, which he made in January 1717 in

favour of his fair Sophia, are preserved in the appendix to

Howell’s Life and Adventures of Selkirk. She must have died

soon after, for about eight years later, "a gay widow, by name

Frances Candis or Candia, came to Largo to claim the property left

to him by his father." Having proved her marriage to him, and the

Will which was dated in 1720, and also his death as Lieutenant of

His Majesty’s ship Weymouth in 1723, her claims were adjusted, and

she left Largo. He does not appear to have had any children. A few

mementos of his undisputed reign in the far-off isle were long

preserved in the old home. Sir David Baxter bought his "kist," and

presented it to the Antiquarian Museum in Edinburgh. His drinking

cup, with the silver rim and wooden foot added by Archibald

Constable, is also there. And his gun is preserved by the

representatives of the late Mr Lumsdaine of Lathallan. The house

in which he was born is demolished; but the accompanying

illustration will recall it to those who knew it, and acquaint

others with its appearance. A recess has been made in the wall of

the upper storey of the house which now stands on its site, and,

there, a striking monument in bronze, designed by Mr Stuart

Burnett, has been placed, at the expense of Mr David Gillies,

net-manufacturer, who is a relative of Selkirk’s. The 11th

December 1885 will ever be a red-letter day in the local calendar.

The triumphal arches, the great processions, the Earl of

Aberdeen’s speeches, and the unveiling of the monument by his

Countess, will never be forgotten. Selkirk would not have been so

famous if De Foe had not elaborated his adventures in the

inimitable "Robinson Crusoe." In the old, crowded burying-ground

of Bun-hill Fields, a striking monument to De Foe is to be seen,

built by the penny subscriptions of his youthful readers; for he

is best remembered by this popular story; while most of his other

works are only known to book-collectors. On Juan Fernandez itself,

a tablet in memory of Selkirk has stood for eighteen years, and

now a statue of Crusoe graces his birth-place.

Largo Bay extends from Kincraig Point to

Methil, a distance of five miles and a half in a straight line,

but much more, of course, on the curve. It is marked, says

Oliphant, "by a ridge of sand..... . . . called by fishermen the

Dike. Of this there is a tradition, although probably not well

founded, among the oldest inhabitants of Largo, that there was

formerly a wall or mound running from Kincraig Point to that of

the Methil, containing within it a vast forrest, called the Wood

of Forth." The roots of the trees of this submerged forest can

still be seen at extra low tides. It is almost superfluous to say

that the bay is well adapted for bathing.

Lundin Mill—or Lundie Mill, as it is

usually called— is so close to Lower Largo that it almost seems to

form a continuation of it. This village is not mentioned by

Sibbald. Perhaps, it did not exist in his time; or, it may have

been so small that he did not deem it worthy of notice. As the

name implies, it grew around the Mill, just as Upper Largo did

around the Church, and as Lower Largo did beside the Harbour. The

mill was there long before Sibbald wrote. Lamont says, that in

October 1657, "William Lundy caused stoole Lundy Mille all new;

the wright that wrought it was James Edee, the said William’s

brother in law. Robert Maitland, Laird of Lundy, gave him two

great elme tries for to stoole the said mule, which grew out

without the deike, betuixt the hayre and coall horse stabell.

(Remember, the said William, at that time, said to the Laird, that

he sould never, in his time, seike any more timber from him for

the said mule.) Robert Bayle at this time was miller ther." This

is the earliest notice which Lamont specially bestows on the old

mill, and it is a pretty fair specimen of his minute entries. He

had previously referred to William Miller, as the miller, in 1652;

and to a spate, in 1655, when "the water entred the mille-doore,

beate stronglie upon the walls of the houses ther, ran over

the head of the bridge, it being biger, by a foote or halfe a

foote then the bridge itselfe." From this entry it appears that

there were at least some houses there at that time besides the

mill. In 1662, the same local chronicler relates that "att Lundy

Mule, the corne kill" took fire, "haveing 11 bolls oatts on hir,

belonging to Symon Cowtrie." The roof was completely burned; and

the three bolls of oats, which were saved, were "ill spoilt." Old

Robert Baillie was "dryster" that day, and William Lundy, master

of the mill. This mill-master bought a part of Boarhills from his

fatherin-law in 1666, for about 5000 merks, but one-half of

that sum was allowed "for his tocher." His wife died, and he took

"a second fitt of distraction," the first being before he was

married. Plainly, he was not fitted to live alone, and so he took

another wife in 1669. Lamont says—"Remember, this marriage was

first proposed be him to hir on a Sabath day att Largo kirke, and

afterward accomplished ther on a Sabath after sermon privatly."

Before his first wife was buried, this other was spoken of at

Lundin House, where she was a servant, as "a fitt woman for his

second wife." And there they supped on the marriage night, dined

the next day, "and went home privatly att night." Whether this old

miller of Lundy took any more fits of distraction, or any

more wives, is not recorded by his gossiping neighbour. In 1837,

the population of Lundin Mill was 453, and at present is probably

rather less. There are some very good villas near the Links, and

the place is popular with visitors. The Postmaster-General has

provided a collecting box for letters, and the inhabitants thrive

well enough without gas. There is a comfortable, homely hotel,

with stabling attached.

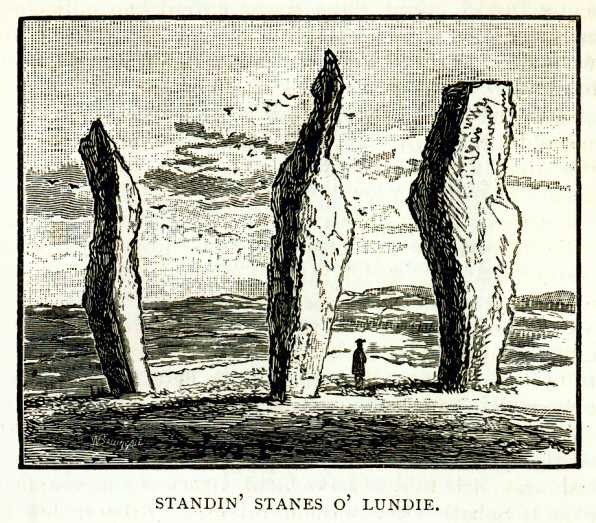

The Standing Stones of Lundin are very

conspicuous objects, nearly half-a-mile further west than the

village.

The illustration conveys a capital idea of the

stones, but a very erroneous one of the stature of the

inhabitants. The most massive of the three is fifteen feet high,

fully two feet thick, and its greatest breadth is about six and

a-half feet. The other two are rather taller, but are not so

substantial. They are supposed to be as deep in the ground as they

are above it. Whether that is quite the case or not, it is

marvellous how such huge blocks of stone could be brought here and

erected at a remote age, when there were no engineering

appliances. The visible portion of the largest must be fully ten

tons in weight. In 1791, Spence Oliphant says:- "There are also

fragments of a fourth, which seems to have been of equal magnitude

with the other three. There is no inscription, nor the least

vestige of any character to be found upon them." It would have

been wonderful if the same remark could still have been made, for

here, as elsewhere, come silly, contemptible wretches, who think

to immortalise themselves, by scratching their unknown names on

monuments of historical or antiquarian interest. It is with no

love for Popish penance that I would suggest that such vandals

should be made to lick out their offensive handiwork. Oliphant

says that "the tradition is, that they are the grave-stones of

some Danish chiefs, who fell in battle with the Scots near this

place." In 1837, Brown adds, that "they are conjectured to be of

Roman origin; by others, to be the gravestones of Danish chiefs,

who fought here and were conquered by Banquo and Macbeth; and, by

others, perhaps, with most probability, to be Druidical remains.

Ancient sepulchres are found near them." That they were raised in

memory of some battle, or in honour of some mighty warriors, is

very probable; but they were certainly not raised to commemorate

any Danish chiefs, who fell under Banquo and Macbeth. It has long

been known that both Banquo, and the Danish invasions in the reign

of Duncan, are inventions of the fertile brain of Hector Boece.

How came you here? Who bade you stand

Grim sentinels o’er sea and land?

Did grateful nation you uprear,

In mem’ry of a patriot dear?

Did some repulsed invader sue

For leave to lay his slain ‘neath you?

Or were your sides, in days of yore,

Of't stained with sacrificial gore?

No picture, symbol, nor a word

You bear, to shew what you record:

Nor threat nor bribe can make you tell

The secret which you keep too well !

Lundin Tower is barely half-a-mile to

the northwest of the Standing Stones. In its solitary grandeur, it

forms a striking feature in the landscape. Until ten years ago it

was hidden by the modern mansion of Lundin, but at that time the

house was demolished; and the old tower left alone. It is said to

have formed part of the old castle, built in the reign of David

the Second—1329-1371—but it is very doubtful if any part of it is

quite as old as that. It has evidently been subjected to many

alterations and additions. The two corbelled turrets may have been

added at a later date, and at that time it was probably

heightened; yet, as a whole, it seems to belong to the early part

of the seventeenth century. Like a great many other old buildings,

it contains a room in which Queen Mary is said to have slept. In

this case, it is a very small one, at the top of the tower; but

the view is magnificent. The Gothic window, however, which now

lightens it, has been inserted. With the exception of the two

small rooms at the very top, there is nothing in the tower except

the staircase. On one of the platforms, the blood-stains of a

tragic murder were pointed out until quite recently; but a new

floor now covers what could not be washed out—and it may he

confidently expected that the antiquated ghost, which has so long

haunted the place, will now be sensible enough to depart. A

fragment of the modern building has been preserved at the base, to

serve as an occasional luncheon room for the worthy owner—Mr

Gilmour of Montrave. The key is kept by the game-keeper, who lives

hard by; but visitors are not desired. Strangers can see really

all that is worth seeing from the outside. The large garden is

turned into a field, although the surrounding walls still remain.

There are also many majestic old trees growing in the

neighbourhood of the tower; and there is the invariable adjunct of

a Fife lairdship—a doocot—which is said to have served originally

as a private chapel, and in the floor of which, according to

tradition, a lucky labourer found a pot of gold. Lamont gives some

curious information about the repairs, alterations, birds, and

incidents of his time. In 1649, the tower-head was covered with

lead at an expense of more than 500 merks Scots. Both the house

and the "dowcoat" were pointed, in 1655, by "one David Browne, in

Enster, a sclater," for which he and his son received 24s Scots

each day for their wages, besides their food. Many alterations

were carried out in 1660 and 1661. At the latter date, "the Lady

caused make a new chemlay fireplace] for the hall of Lundy, of the

newest fashion, with long barrs of iyron before, with a high backe

all of iyron behinde. It was meade by one Androw Mellen, smith in

Leven. It was about 12 stone weight, and more, at 5 markes the

stone, so that, one way or other, it stood neire fowre pound

sterling." Ten years afterwards a new bake-house and brew-house

were added, and for the second time the hall was adorned with new

green cloth hangings, "with stampt gilt leather betwixt every

peice." In 1653, the chronicler, who was factor on this estate,

planted some elms and firs in the south quarter of the garden

yard. The previous year Captain Weilkesone, of Fairfax’s regiment,

who was quartered at Lundin, "caused the chirurgion..... . . . .

to draw blood of his whole company." Possibly, they had not lost

much in active service! The Laird of Lundin had been taken

prisoner at the battle of Worcester, in September 1651 ; but in

1652, Cromwell let him home for four months, and again in 1654 he

got a pass. In September 1657, he returned for the third time to

his beautiful estate, but only to die of consumption. He lingered

until December 1658, when he passed peacefully away, and, eight

days later, "was interred at Largo church, att night, with

torches." He was only 36, and his son, who had been educated at

Cupar and St Andrews, died in 1664, when he had barely reached his

majority. The young man was buried with so much pomp, that Lamont

devotes a whole page to an account of the funeral and the expenses

incurred. The details are very interesting, but are too numerous

for quotation. Three trumpeters and four heralds marched before

the coffin. Ten dollars were given to the poor, forty-eight

dollars to the trumpeters, and about eight hundred merks to the

heralds and painters. The mournings cost more than £1000, the

claret £200, the tobacco £7, and the beef £84 12s. The man who

dressed the coach got seven dollars, and "the Kirkekaldie man,"

who made the coffin, £40. Lamont records a curious and fatal

accident that happened here two and a-half years before the young

Laird’s death. As it would be unfair to abbreviate his quaint

account, it is given entire:- "1662, July 5, being Saturns

day.—The said day, betuixt 7 and 8 in the morning, at Lundy, in

Fyfe, John Rattray, one of the plowmen ther, being in the garden

yearde, sneding tries on the north dyke, over against the coall

stabell, for the gyle-house , Alexander Cuninghame, elder, in

Lundy Mille, came into the yearde, and stoode a litell under the

place wher he was sneding, the said Johne crying if ther were any

body ther to bewarre and remove, for the branche was falling

downe; the said Alexander, not regairding, was immediately smitten

with it to the grounde, and dyed presently of the stroake, his pan

being broken, and his necke almost, so that he was never hard

speake a worde after. After which, he was taken up, and placed on

a deal at the garden yeate, till James Murray, wright, meade a

coffin to him, and that same day, in the afternoone, he was

interred at Largo Church, in the east end of the said church

yearde."

Lundin Links lie to the south-west of

the village, and are the favourite resort of the golfers, who

spend their holidays in Lower Largo, the Kirkton, and Lundin Mill.

Lamont relates that while a party of Cromwell’s soldiers were

passing through the Links on a summer evening in 1654, two of

Kenmuir’s men charged the two foremost, and, having shot one of

their horses, retired. They were quickly followed, but escaped.

The English, in revenge, returned to Newburn, where they surprised

some of the rest of Kenmuir’s men, of whom they wounded four or

five, and took as many prisoners. A man and a woman were shot with

one bullet, and other two women were struck. From Newburn they

went to Easter Lathallan, where they took Lathallan Spence’s son

prisoner. Late the same night, they reached Lundin again, and

having set young Spence free next morning, and leaving one

badly-wounded prisoner behind them, they marched off with their

seven or eight captives to Burntisland. The prisoner they left

behind died next day, and one of the wounded women had to get a

leg cut off. Robert, the fourth Viscount of Kenmuir, suffered much

in the cause of Charles the Second, and was excepted by Cromwell

from his act of grace and pardon in 1654.

Largo Law is a very prominent hill to the

north of the Kirkton, and is seen from a great distance. In

troublous times it was used as a beacon-hill to warn the people of

approaching dangers. As it is 965 feet high, it well repays

enthusiastic climbers, by the magnificent view which is to be had

from the summit.

Kiel’s Den, which is nearly two miles in

length, is immediately to the north of Lundin Mill. It is

beautifully wooded, and some of the vista views are very fine. Few

places are better suited for a quiet stroll, and its pleasant

glades arc the beloved haunts of many a picnic party.

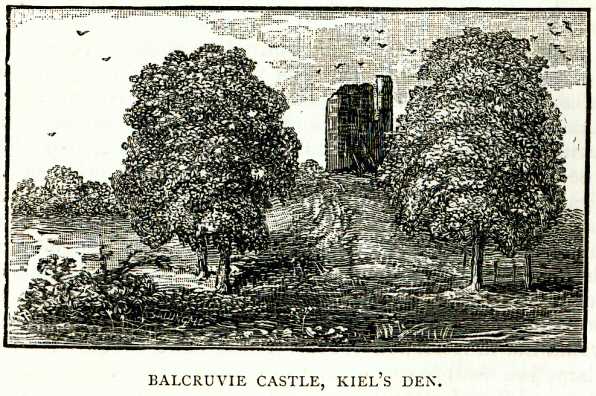

Pitcruvie Castle is picturesquely situated

on the verge of the upper portion of Kiel’s Den. It is sometimes

called Balcruvie. The most direct way to reach it, and the easiest

way to find it., is to take the road which leads from Largo to

Ceres. It. is so conspicuous, with the romantic den on the one

side and a prosaic farm-steading on the other, that it cannot be

missed. The walls are wonderfully entire, but the stones are very

weather-worn. It has been a great massive keep, much the same as

Scotstarvit Tower, near Ceres. Two of the flats have had vaulted

floors, and the remains of the circular tower, which contained.

the stair-case, can still be seen at one of the corners. This

tower seems originally to have been corbelled out, and to have

been afterwards supported from the ground. Near another corner the

foundation of the stair can be seen which led to the first flat.

The two vaulted chambers, on the ground floor, must have been used

as dungeons, or store - houses, as the only entrance was by a

trap-door from the room over-head. It is said that the castle

belonged in ancient times to the Ramsays, and that a daughter of

that family married David, second Lord Lindsay of the Byres, who

was distinguished for his bravery in foreign wars, and for his

devotion to James the Third. According to Pitscottie, Lindsay gave

that monarch his "great gray courser," which, "if he had ado in

his extremity, either to flee or follow," was able to "war all.

the horse of Scotland, at his pleasure, if he would sit well." The

King, however, was not able to "sit well;" and so, in his flight

from Sauchie Burn, he fell off the great gray courser at the fatal

Beaton’s Mill. Pitscottie also tells how Lindsay and the others,

who had assisted James the Third, were summoned to appear at

Edinburgh, and records the bold but informal speech of Lord David,

who was "a rash man, of small ingyne and rude language, although

he was stout and hardy in the fields." The Chancellor craftily

advised him to submit to the will of the King; but David’s.

brother, Patrick, who was versed in the law, tramped on his foot

as a hint that he should not. Unfortunately, he had a sore toe,

and "the pain thereof was very dolorous," and so he angrily

exclaimed:- "Thou art over peart, lown, to stramp on my foot, were

thou out of the King’s presence, I should take thee on the mouth!"

Patrick, seeing that the case was desperate, fell on his knees and

craved leave to plead for his brother. When his desire was

granted, he managed, by pointing out first one informality and

then another, to remove the King from the bench, and to induce the

Lords to "cast the summons." Lord David was so delighted now with

his brother, that his gratitude thus burst forth:- "Verily,

brother, you have fine pyet words, I would not have trowed that

you had such words. By St Mary, you shall have the Mains of

Kirforther for it!" The Mains of Kirkforthar was a poor

recompense; for the King was so displeased at Patrick, that he

declared, "He should gar him sit where he should not see his feet

for a year;" and he kept his word. Lord David died in 1492, and

was succeeded by his brother John, who died without male issue in

1497. .At the latter date, Patrick, of the "fine pyet words,"

became fourth Lord Lindsay of the Byres. He accompanied James the

Fourth to Flodden, and advised that the King should not hazard

himself in the battle, at which James was so furious that he

vowed, he would "cause hang him on his own gate," when he returned

to Scotland. As one of Lord Patrick’s sons, who died before him,

was styled Sir John Lindsay of Pitcruvie, it has been inferred

that the estate had passed into the hands of the Lindsays by the

marriage of Lord David. In his History

of Fife, Leighton

expresses the opinion, that it was Sir John, who acquired the

lands of Pitcruvie by marriage, and built the castle. Leighton

also states that Pitcruvie was sold to "James Watson, Provost of

St Andrews, whose grandson, James Watson, was served heir to him

in the lands of Pitcruvie, Auchindownie, and Brissemyre, on the

8th of March 1664."

Norrie’s Law is exactly three miles

north from Largo Pier. Robert Chambers, in his Popular Rhymes

of Scotland, gives the following curious traditional account

of its origin:—"It is supposed by the people who live in the

neighbourhood of Largo Law in Fife, that there is a very rich mine

of gold under and near the mountain, which has never yet been

properly searched for. So convinced are they of the verity of

this, that whenever they see the wool of a sheep’s side tinged

with yellow, they think it has acquired that colour from having

lain above the gold of the mine. A great many years ago, a ghost

made its appearance upon the spot, supposed to be laden with the

secret of the mine; but as it of course required to be spoken to

before it would condescend to speak, the question was, who should

take it upon himself to go up and accost it. At length a shepherd,

inspired by the all-powerful love of gold, took courage, and

demanded the cause of its thus ‘revisiting,’ &c. The ghost proved

very affable, and requested a meeting on a particular night, at

eight o’clock, when, said the spirit:

"'If Auchindownie cock disna craw,

And Balmain horn disna blaw,

I’ll tell ye where the gowd mine is in Largo Law.’

"The shepherd took what he conceived to be

effectual measures for preventing any obstacles being thrown in

the way of his becoming custodier of the important secret, for not

a cock, old, young, or middle-aged, was left alive at the

farm of Auchindownie; while the man, who, at that of Balmain, was

in the habit of blowing the horn for the housing of the cows, was

strictly enjoined to dispense with that duty on the night in

question. The hour was come, and the ghost, true to its promise,

appeared, ready to divulge the secret; when Tammie Norrie, the

cow-herd of Balmain, either through obstinacy or forgetfulness,

‘blew a blast both loud and dread,’ and I may add, ‘were ne’er

prophetic sounds so full of woe,’ for, to the shepherd’s mortal

disappointment, the ghost vanished, after exclaiming:

"‘Woe to the man that blew the horn

For out of the spot he shall ne’er be borne.’

"In fulfilment of this denunciation, the

unfortunate horn-blower was struck dead upon the spot; and it

being found impossible to remove his body, which seemed, as it

were, pinned to the earth, a cairn of stones was raised over it,

which, now grown into a green hillock, is still denominated

Norrie’s Law, and regarded as uncanny by the common people." This

tradition was taken down by Chambers in 1825. There is another

local tradition, according to which, Norrie’s Law covered "the

chief of a great army, buried there with his steed, and armed in

panoply of massive silver;" but it has been suspected that it

originated after the wonderful discovery of nearly seventy years

ago. Spence Oliphant must either have been ignorant of these

traditions, in 1791, or thought they were not worth recording,

for, after describing Largo Law, he merely says:- "Besides this,

there are 2 other Laws. But it is evident that these have been

artificial. When the cairn was removed from one of these, a few

years ago, a stone coffin was found at the bottom. From the

position of the bones, it appeared that the person had been buried

in a singular manner. The legs and arms had been carefully severed

from the trunk, and laid diagonally across it." No archaeologist

can refer to Norrie’s Law, without experiencing a mingled feeling

of anger and bitter chagrin; for, in or about 1819, there was

found here, only to be destroyed, "the most remarkable discovery

of ancient personal ornaments and other relics of a remote period

ever made in Scotland." Daniel Wilson, in his Pre-Historic

Scotland, devotes a chapter to the Norrie’s Law relics, and

vigorously denounces—yea, almost curses—the pedlar who purloined

the valuable ornaments and sold them for old silver. It has been

computed that nearly 400 ounces of pure bullion were found in

Norrie’s Law. Unfortunately, almost the whole of it was melted

down; although, from an antiquarian point of view, it was of

priceless value. The jeweller in Cupar, who paid £25 to the pedlar

for some of it, had a vivid recollection, even after a lapse of

twenty years, of "the rich carving of the shield, the helmet, and

the sword-handle, which were brought to him, crushed in pieces, to

permit convenient transport and concealment." Having heard of the

discovery, General Durham caused a search to be made at the base

of the Law, in 1822, and a number of interesting silver relics,

weighing in all about 24 ounces, were found. Several of these were

presented to the Antiquarian Museum in Edinburgh in 1864, and the

remainder in 1884. A description of them, by Dr Joseph Anderson,

will be found in the eighteenth volume of the Proceedings of

the Society of Antiquaries. They embrace two penannular

brooches of hammered silver, two leaf-shaped plates of solid

silver, three pins, a band of silver, a spiral finger-ring, a disc

of thin plate, a portion of plate, two portions of an arm-band, a

thin riband, a fragment of a chain of fine silver wire, a large

quantity of fragments, clippings and broken pieces of thin plates

of silver, and a brass coin. These specimens have led to the

abandonment of the idea of silver armour. The ornamentation is

distinctly Celtic. And each of the leaf-shaped plates bears the

symbol of the double-disc and broken rod, which occurs so

frequently on the sculptured stones. There is only one other

instance known of this symbol appearing on metal work, to wit, on

the terminal link of a silver chain found in Lanarkshire. The

tumulus of Norrie’s Law was surrounded by a ditch, or fosse, on

the outer side of which there was a wall. "On the inner side of

the ditch the base of the Law was defined by a circle of large

boulders. Portions of an inner concentric wall were also observed.

Between these walls a quantity of travelled earth was found, and

within the inner circle the eminence was mostly formed of a cairn

of stones. Here, towards the centre, vestiges of charred wood

appeared, and many of the stones of the cairn showed that they had

been under the action of fire. A small triatigular cist, found in

the foundation of the outer base of the Law between two of the

stones, and covered with a flat stone, contained incinerated human

bones. On the west and on the outside of the base in which the

triangular cist or hole was discovered, a small urn of baked clay

was found lying on its side among charred wood. Nothing was found

in the urn. The tumulus rests on a hillock of sand on the summit

of a ridge commanding an extensive view." It had doubtless been "a

pagan grave-mound of Bronze Age type." The silver relics were

found, not in the grave-mound, but in the sand at its base, and

are believed to belong to the seventh century. Largo has been rich

in valuable antiquities, for in the winter of 1848, four golden

torcs were found at Temple. They are made of thin fillets twisted

like a screw, and have hook-like terminations, which interlock and

fasten them round the wrist of the wearer. Three of them are

perfect, and all are now in the Edinburgh Antiquarian Museum. An

old woman, who had lived all her life where they were found,

stated that in her young days several cists were discovered there,

and that a man was supposed to have found a treasure, for he

suddenly became wealthy enough to build a house.

Backmuir of Gilston is a long,

dilapidated village in the northern part of the parish. In 1837,

the population, including that of the neighbouring hamlet of

Wood-side, was 316, but it is probably much less now.

The Population of the whole parish in

1755 was 1396; in 1791, it had risen to 1913; in 1861, it had

still further increased to 2626; but in 1881, it was down to 2224.

The Valuation in 1855-6 was £14,438 12s,

and rose to £15,829 11s 10d in 1874-5; but has fallen to £14,258

6s 4d in 1885-6.

Click here to see some

pictures of Largo