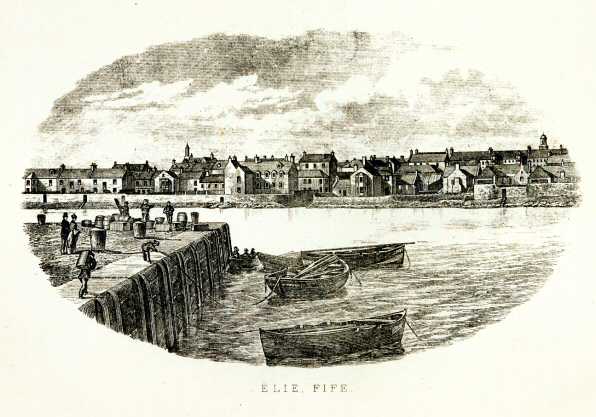

This favourite

little watering-place is two miles further up the Firth than St

Monans.

The Name, which is

sometimes spelt Ely and Ellie, is supposed to be derived “from A

Liche, in Gaelic, ‘out of the sea, or out of the water,’ the town

being built so near the sea that it washes the walls in some

places.” Dr Milligan, on the other hand, held that it had “sprung

from the Greek word, ‘elos’ a marsh;” and Wood, dissatisfied with

both theories, thought it meant “‘the island,’ that is, the island

of Ardross, and the land at the harbour being surrounded by the

sea before the dyke was built, probably was the origin of the

name.” In the parlance of the district it is commonly called the

Elie.

The Town is older

than the parish, but how old is uncertain. In 1586, James Melville

speaks of landing in a boat at the Alie, “efter a maist weirisome

and sear day.” It has long been a burgh of barony; and it

consented by its deputy to the union with England, in 1651, on

which occasion it was styled in the records Elymburgh. In 1672,

the weekly market was changed by Parliament from Sabbath to

Tuesday. Two yearly fairs had been held, on the 1st of May, and

the 20th of August, since the days of James the Sixth, who had

granted the privilege; but, in 1672, they too were changed. Three

were now to be held, viz., on the 13th of January, 7th of July,

and 20th of October; but the market and fairs have long been

discontinued. In 1699, the proportion of taxation payable by the

unfree traders of Fife, for the communication of trade, was set

down at 17s 5d. Of that sum the undermentioned places paid as

follows

“By Elie one

shilling six pennies.”

“By toun and paroch of Saint Minnans six pennies.”

“By the paroches of Kilconqr and Newburne eight pennies.”

“By toun and paroch of Largo eight pennies.”

“By toun of Leven and paroch of Scoony one shilling.”

An offer of eight

pence by Elie in 1700 was rejected as too small. In 1705, Sir

Robert Forbes, in name of the Royal Burghs, protested against this

burgh receiving the privileges of a Royal Burgh. It is described,

in Chambers’ Gazetteer of Scotland, as “an ancient little town of

no trade,” and as “excessively dull.” But though it is nine and

thirty years more ancient now, it is certainly not excessively

dull. It is a delightfully quiet retreat, for those who wish to

escape from the din and bustle of the city, to rusticate where

they can enjoy the combined advantages of a sea-side resort and

country town. The streets are wide and clean, the air is clear and

bracing, the beach is splendid for bathing, the rocks are wild and

rugged, the water supply is abundant and excellent, there are many

beautiful walks and drives in the neighbourhood, and the golfing

links of Earlsferry are close at hand. There is an “Elie

Golf-House Club,” an “Earlsferry and Elie Golf Club,” and also a

Cricket Club, a Lawn-Tennis Club, and a Curling Club. As Elie is

likewise easy of access by rail, road, and sea, it is sure to rise

much higher in popular esteem. Although Earlsferry is so near that

it seems to be part of the same town, it is in the parish of

Kilconquhar, and is under different municipal control. I therefore

treat it in a separate chapter. Elie is governed by nine Police

Commissioners, of whom three are Magistrates. These also form the

Local Authority, and the Police Act of 1862 has been wholly

adopted.

The Parish

Church stands in the burying-ground in the middle of the town.

From a lengthy Act of Parliament passed on the 17th of November

1641, it appears that the then lately deceased Sir William Scott

of Elie was anxious to build a kirk in the town of Elie, within

his lands and barony of Ardross, and left 5000 merks for that

purpose. His son and heir built the church, and mortified a

stipend for the minister with a manse and glebe. The patron and

minister of Kilconquhar consented that Scott’s lands should be

erected into a separate parish. The Presbytery of St Andrews, the

Synod of Fife, and the General Assembly all agreed, and therefore

the King and Estates now ratified the mortification and contracts,

and erected the lands into a separate parish and the new kirk into

a parish kirk, to be called the parish and kirk of Elie. The

building cannot have been very substantial, for in 1670, William

Scott of Ardross was empowered to lift the vacant stipend, that he

might repair the kirk and manse, which had become ruinous, and

like to fall to the ground. The steeple was built in 1726, and the

church “underwent a complete repair in 1831.” In the east gable of

the church, on the south side of the porch, the top of an old

table stone has been built in. It has a richly carved border, and

is in memory of Thomas Turnbull, sen., of Bogmill—a pious,

upright, and modest man, who died in 1650. A bull’s head occupies

a prominent place in the coat of arms. A much more remarkable

tombstone has been built into the outside of the north wall of

the porch, in memory of Elizabeth,. second daughter of Thomas

Turnbull of Bogmill, who died on the 3d of January 1658. It shows

a full-sized skeleton, covered from the breast to the ankles by a

cloth, which is attached to a roller on either side, and on this

there is a winged hour-glass. Altogether, it is most peculiar, and

almost conveys the idea of an Egyptian mummy, with the head and

feet protruding. There are engravings of several stones of

somewhat similar design, in Cutts’ Manual of Sepulchral Stabs and

Crosses of the Middle Ages. The first minister of the parish

church has also been its most eminent. Robert Trail, a descendant

of the Trails of Blebo, was born in 1603, and after finishing his

course at St Andrews University went to France. He returned to

Scotland in 1630, and became chaplain to. the Marquis of Argyle.

He was presented to Elie by the Laird of Ardross, and admitted on

the 17th of July 1639. When the Scots army was in England, he

attended it for several months as chaplain, and was present at

Marston Moor. He took an active part in the public affairs of the

Church, and was translated to the Greyfriars’ in Edinburgh in

1649. In the unhappy controversy which soon afterwards divided the

Scottish Church, he took the side of the Protestors; and was one

of the few who met on the 23d of August 1660, to draw up a

supplication to Charles the Second. For daring to prepare a

petition, they were seized and imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle.

Next March, some of them were brought before the Lords of the

Articles. Trail alone seems to have been brought before

Parliament. His manly Christian speech on that occasion has been

preserved by Wodrow, in his History of the Sufferings of the

Church of Scotland. On the 11th of December 1662, the Privy

Council banished him forth of his Majesty’s dominions. He went to

Holland in March 1663; but even there persecution followed him.

Steven, in his history of the Scottish Church in Rotterdam, says

that the King, in 1670, formally asked their High Mightinesses to

expel Trail and other two Scotch ministers from Holland. Steven

adds that he “secluded himself for a while, and afterwards lived

unmolested in Holland till his death, which took place several

years afterwards.” Wodrow states that he returned and died in

Scotland, and Hew Scott gives the 12th of July 1678, as the date

of his death. But in a letter written by Macward—one of his

fellow-exiles—in 1677, he is spoken of as already dead, and it may

be inferred from that letter that he died abroad. Macward places

him among the great luminaries who had preached to the Scottish

congregation at Rotterdam, and describes him as “fervent, serious,

and zealous.” He had three sons and three daughters. The eldest

son William became minister of Borthwick, and his son, grandson,

and great-grandson successively occupied the pulpit of Panbride

from 1717 to 1850. His third son James was Lieutenant of Stirling

Castle; and his second daughter Agnes was married to Sir James

Stewart of Goodtrees, one of the authors of Naphtali, and

Lord-Advocate after the Revolution. But his second son Robert, who

was born at Elie in 1642, was most widely known. He was a staunch

Presbyterian, and was bold enough, when only nineteen, to

accompany James Guthrie to the scaffold. Six years later he had to

fly to Holland to his father; but in 1670 he was ordained in

London, and preached in Kent for several years. In 1677, he

returned to Edinburgh, where he was seized by Major Johnston, who

received £1000 Scots for apprehending him. He was sent to the Bass

for three months. Often would he look wistfully across the water,

from his sea-girt prison, to the peaceful little town where he had

first seen the light, and spent his early years. After being

released he returned to Kent, and for many years was minister of a

congregation in London, where he died in 1716, having lived to

see the overthrow of the Stuarts, and the union of the two

kingdoms. “His writings are essentially English— clear, nervous,

and Saxon—while the catholicity of their sentiments made them a

favourite with every class of religious men both in England and

Scotland.” Of those printed in his lifetime, his Discourses on the

Throne of Grace are best known.

Antiquities of South Street.—There

is a fine old door-way at the east end of this street, a very good

drawing of which is given in Leaves from my Sketch Books. Mr Small

there says that :—“ It is rather unique in its heavily trussed

pilasters, elaborately carved on both face, and ingoe, which is

much weather worn, as well as the frieze and cornice.” He remarks

that Elie does not possess any other old remains of value. The

next door to the west, save one, is surmounted by an ornamental

stone showing the sun, moon, world, and three stars. The door

immediately to the west of this has a most imposing stone

door-case, with a frieze, crowned by a composite sun-dial, and

dated 1682. It bears the initials of Alexander Gillespie and his

wife, Christian Small, and also the Gillespie arms. [On the west

side of the church-yard gate, there is a mural monument, bearing

the same arms; but the old inscription has been hewn off to make

way for one more modern.] A large building called the “Muckle

Yett,” stretching half-way across the street, formerly stood here,

and this door-case belonged to it. Two centuries ago the Duke of

York, afterwards the ill-fated James the Seventh, lodged in it,

when he came to see the Earl of Balcarres and the Laird of

Ardross. “There is a dim recollection of a bed,” says Wood, “with

satin hangings, apple-green, and a darker shade of the same

colour, and the arms of Scotland on the bolster-piece, which the

Duke used to occupy when he came over from Holyrood, and his barge

cast anchor in the road-stead of Elie.” The coxswain of his barge

fell in love with the daughter of Turnbull of Bogmill, and the

Episcopal minister of Kilconquhar married them privately. That

York might not be blamed for carrying her over in his barge, the

bride consented to be put into a barrel with a sparred top. Those

who were inquisitive enough to ask what was in the barrel were

promptly told that, it was a swan from Kilconquhar Loch. Wood has

preserved the old song written on this episode :—

“At Elie lies a

gallant barge,

And her sails as white as snaw,

With the royal standard at her mast,

And her gilded sides and a’.

Sing a’ and sing a’; sing Elie leddies, a’,

Bewaur the Duke o’ York’s lads when they

come here awa’.

“Up the lang turnpike,

And at the brass Ca’;

The leddy liked the sailor weel,

And wi’ him she ran awa’.

Sing a’, &c.

“They stowed the maiden in a cask,

and bore her to the shore;

And it’s fare ye weel my father’s house,

And Elie evermore.

Sing a’, &c.

“Old Bogmill he took it ill,

That his daughter was awa’,

And to Holyrood, and to the Duke,

And telt him o’ it a’.

Sing a’, &c.

“Oh! woe be to Kinneuchar priest!

An ill death may he dee!

He’s wed my lass to an English loon,

And that has ruined me.

Sing a’, &c.

“The Duke he answered by his faith,

Likewise his royalty;

No lady was aboard the barge,

That ever he did see.

Sing a’, &c.

“Stand up, stand up now, gude Bogmill,

From off your bended knee;

I’ll mak’ your son a captain,

And he shall sail wi’ me.

Sing a’, &c”

The Subscription

Library, containing about 4000 volumes, is open daily to town and

country readers. Membership only costs 6s per annum.

Elie House

was built by Sir William Anstruther, who bought the estate in or

about 1697. Mr Baird is now the owner, and the grounds are kept

strictly private. Within them, not far from the Railway Station,

stands an obelisk nearly thirty feet high; but no one seems to

know what it was raised to commemorate. Some suppose that it was

in memory of a great battle, others imagine that it was in honour

of the union of the kingdoms, while some authoritatively assert

that it only marks the burial-place of a favourite dog! On the

east and west sides there are panels for inscriptions, which have

never been lettered. On the south side there is a head carved in

high-relief which might pass either for a dog’s or a lion’s, but

it is much wasted. On the north side there is a slab bearing the

arms of the Anstruthers, which are also very weather-worn, both of

the supporting falcons having lost their heads, and each being

minus a foot, while only the last word of the motto remains. The

carved stones look much older than the monument. Sir John

Anstruther, the third baronet of this branch of the family, wrote

a book on drill husbandry, which was published in 1796. One of his

friends remarked that no one could be better qualified to write on

the subject, as there was not a better drilled husband in Fife.

The Harbour.—Wood

states that a royal charter of the port was granted in 1601.

Lamont relates that on the 20th of July 1651—” The towne of

Bruntellande did render to the English armie; the garesone ther

had libertie to goe foorth with flieing coullers and bage and

baggage. The said day also, a pairtie of ther horse came alonge to

the Ellies towne, at which tyme Jhone Small’s ship was taken out

of the harbery, and mead a pryse of.” In 1696, a petition was

presented to the Privy Council craving help to repair the harbour,

as it was in a ruinous condition, and urging as a reason that

three hundred of his Majesty’s soldiers would have been lost, had

it not been for the conveniency and safety of this harbour. The

Lords of the Privy Council were so impressed with the importance

and necessity of the case, that, they authorised a collection to

be made in all the parish churches of the kingdom. In 1710,

Sibbald pronounced the harbour to be most convenient and safe.

“The water in it at spring tides,” he says, is “twenty-two foot

deep. A little to the east of this there might be a harbour made

for ships of the greatest burden, and in which lesser ships might

enter at low water, and be as safe as the other.” In 1795, William

Pairman, the minister of the parish, said it was again “going fast

to ruin,” though it could be repaired at an inconsiderable

expense. He declared it to be “the resort of more wind-bound

vessels, than any other harbour, perhaps, in Scotland.” And he

thus refers to the haven on the east side of it:— “ To the east

end of the harbour of Ely, and at a small distance from it, Wade

haven is situated; so named, it is said, from General Wade, who

recommended it to government as proper for a harbour. Others call

it Wadd’s Haven. How it got that name, if the right one, is not

known. It is very large, and has deep water, in so much that it

would contain the largest men-of-war, drawing from 20 to 22 feet

water.” In John Ainslie’s map of Fife and Kinross, published in

1775, it is neither called Wade nor Wadd, but Wood Haven. Pairman

also states that, in 1 795, there were, “belonging to this place,

seven square-rigged vessels, carrying 1000 or 1100 tons, all

employed in foreign trade, and one sloop used as a coaster.” He

further notifies that “vessels of a considerable size are built

here;" and that there were eight fishermen, who had houses rent

free from Sir John Anstruther, on condition of supplying the town

with fish at least thrice a week. The harbour of Elie now serves

for Earlsferry as well, and yet there are only twelve

fishing-boats, with twenty men and boys. There is a rocket

apparatus in connection with the Coast-Guard Station.

The Lady’s Tower

- Sauchar Point, is a conspicuous and picturesque object. It was

built as a summerhouse for one of the Lady Anstruthers, and there

were old people, twenty years ago, who remembered when it had a

roof and glazed windows. The diameter inside is about 15 feet, and

it has been lathed and plastered. There are three pointed windows

and a door-way, and also a fire-place and a press. A bathing

place, with a sluice, was close by. Some people have made a

livelihood by gathering Elie rubies or garnets, which are found

here. Searching for these gems is an agreeable pastime to

visitors.

Ardross Castle,

which was long the seat of the Dischingtons, and afterwards of the

Scotts, stood half-way between Elie and St Monans. It has fared

much worse than Newark Castle, for only a vestige remains, on the

cliff between the railway and the beach. A sheep-washing

apparatus has been fitted up in one end of it. In one of the

fields near this, a curious subterranean building was discovered

last century. Several coffins are said to have been found in it,

“ranged in the shape of a horse-shoe,” and some of the bones were

of “a remarkably large size.”

Bucklevie

was the name of a village, which stoodbetween Elie House and

Kilconquhar Loch, and which was cleared away by Sir John

Anstruther, about 1760, to please his wife, who is said to have

been “a very superior woman.” According to tradition, an old

woman, who lived in it, predicted that the family should not

flourish for seven generations. Dr Milligan, in 1836, says : —

“The prophecy is still devoutly believed by a number of people;

and the fact has added strength to their faith,—the sixth

proprietor, within the memory of middle-aged men, being now in

possession, and some disaster having occurred in the history of

them all.” Another version will have it, that the old woman stood

on a stairhead, when the demolition had begun, and cursed the lady

and her race to the third generation. Whether this was the cause

or not, the unlucky estate has passed out of the hands of the

family. The effigy of “Jock o’ Bucklevie” is in the burying-ground

of Kilconquhar.

Praying Society and Covenanters’

Conference. —During the persecution, under Charles the Second,

and James the Seventh, many of the Presbyterians kept up praying

societies in the districts in which they lived. The stricter and

more uncompromising of these—the followers of Cameron, Cargill,

and Renwick—were emphatically known as the “Society People.” The

Records of this “suffering remnant in the Church of Scotland, who

subsisted in select societies, and were united in general

correspondencies during the hottest time of the late persecution,

viz, from the year 1681 to 1691,” were published by John Howie of

Lochgoin, in 1780, with the appropriate title of Faithful

Contendings Displayed. Some of the Society People doubtless showed

“more zeal than knowledge, more honesty than policy, and more

single-hearted simplicity than prudence,” in their anxiety to

avoid “the defections, compliances, sins, and snares of the time;”

yet “the unbiassed and unprejudiced may discover much ingenuity,

and somewhat of the Lord’s conduct, and helping them to manage and

keep up the testimony, according to their capacities, and stations

in these meetings.” On the 11th of June 1681, one of these

societies, in Fife, agreed to a paper called A Testimony against

the Evils of the Times; and on the 11th of next month, three of

the members, to wit, Laurence Hay, Andrew Pittilloch, and Adam

Philp, were tried before the Justiciary for signing it, and were

sentenced to be hanged in the Grassmarket of Edinburgh on the next

day save one. There is reason to believe that Hay was born in West

Anstruther in 1649, and Wodrow says he was a weaver. Pittilloch

was a land-labourer in the parish of Largo. Both of them were

executed on the 13th of July, and, in conformity with their

sentence, their heads were stuck up on Cupar tolbooth. As

Crookshank has justly said, their dying testimonies, which are in

the Cloud of Witnesses, “breath a spirit of true piety.” Philp

seems to have been respited, and to have afterwards escaped. James

Russel—” a man of a hot and fiery spirit “—who had taken a leading

part in the death of Bishop Sharp, introduced dissension and

confusion, at a general meeting of the Society People, held at

Tala-linn, in Tweedale, on the 15th of June 1682, by endeavouring

to make the paying of customs at ports and bridges a testing

question. He afterwards prevailed on the Fife Society to withdraw

from the others; and to adopt his extreme views on that point, and

also on the names of the days of the week and months of the year.

At a general meeting, convened near Glasgow, on the 28th of

November 1683, a deputation was appointed to go to Fife, to invite

that society to come and hear the Gospel preached by Renwick, who

had returned from Holland. It was risky for these people to

travel, and highly dangerous to hold meetings; nevertheless, on

the 14th of December 1683. “three men and a boy, and about seven

or eight women” convened at Elie to meet the deputation. Before

imparting their commission, the deputation wished one of their own

number to pray, but as the Fife folk refused to join in this with

them, they forbare, and delivered their message after this manner

:—“ The General Meeting hath sent us to acquaint you, that the

Lord out of His free love and infinite mercy bath visited His poor

people in their low condition, in giving us the sweet and precious

Gospel again, in stirring up Mr James Renwick a minister,

faithfully to preach the same, and freely to testify against the

sins and abominations of the time, to which we have been witness

both in private and in public; and considering our being bound in

covenant together, and out of brotherly love and kindness to your

souls, they earnestly desire and invite you to come and hear the

same, and be partakers of that rich and unspeakable blessing the

Lord hath bestowed.” The dozen Fifers, however, were immovable.

They would hold no communion with those who paid customs at ports

and markets, although they were willing to pay them at boats and

bridges. None of the Society People would pay cess expressly

]evied to maintain soldiers to hunt them down; and the deputation

acknowledged that they would not justify the paying of customs;

but they said they “could not drive so abruptly and

inconsiderately to such a height of separation on that head.” And

yet the representatives of the Fife Society would not give way.

“All the ground they gave for refusing to hear the said Mr James

preach, was only this, that he does not as yet see the paying of

customs, and joining with those who pay the same to be a ground of

separation, and of debarring from the privileges of the Church.”

The Parish,

as already mentioned, was erected by Parliament in 1641.

Altogether it contains fully 2241 acres, including 210k of

foreshore; but as Scott’s lands were not all contiguous, 650 acres

are detached from the rest. Population, Public Buildings, &c.—In

1755 the population of the parish was only 642, and in 1790 it had

decreased to 620. In 1831 the inhabitants had increased to 1029,

but in 1881 they had sunk to 670. At the latter date there were

625 people in the town, of whom 79 were in Kilconquhar parish. In

Elie, there are two hotels, a branch of the National Bank, a

Savings’ Bank, a Post and Telegraph Office, and a gas-work. The

Free Church, which is dated 1844, is a peculiar looking building.

In 1795, Pairman wrote:- “There are a few Seceders, Independents,

and Bereans; but the great body of the people belong to the

Established Church. The stipend of Ely is £80 old stipend, and £20

lately given voluntarily by Sir John Anstruther—in all £100. The

schoolmaster’s salary is £11.” The valuation of the parish in

1855-6 was £5053 18s. It has gradually risen until it has now

reached £7333 12s. In 1836, Dr Milligan said :—“There are no

antiquities in the parish, nor yet any modern buildings worthy of

notice:" but, “it has often been remarked by strangers that on

Sundays the church, from the cleanliness of the people, and in

many instances the handsomeness of their dresses, presents much of

the appearance of a city congregation.” At that time, there was

no Dissenting Church in the parish, and not more than 15 of the

parishioners were members of Dissenting Churches; but these were

“divided among perhaps half a dozen different sects.” Under the

head of “eminent persons,” Dr Milligan stated:- This is a

production in which the parish does not appear to be very

prolific.” Since that time his own eldest son has risen to great

eminence in the Church, but he was not born in Elie. In the very

year, however, in which he wrote, a most distinguished native

rested from his labours. Few men have done more for the safety of

their fellows than James Horsburgh, the self-taught and

enthusiastic hydrographer, who was born at Elie in 1762, who died

in 1836, and was buried here.

Click here to see pictures

of Elie