|

The Sculptured Stone

monuments of Scotland may be considered the earliest existing expression of

the ideas, and the most genuine records of the skill in art of the early

inhabitants of Scotland; but now, when attention has been directed to them

it is found that they are diminished in numbers and in many cases mutilated

in their form. It is therefore satisfactory to know that in Easter Ross is

found a number larger and of more exquisite workmanship than have yet been

discovered in any one district in Scotland.

It has been supposed that the sculptured standing stones succeeded the rough

unhewn obelisks which appear so frequently in Scotland, or that Christian

sculptures were put on pillars previously erected, and it was a primitive

custom to erect stones for purposes of devotion, memorials of events, and

evidences of facts even down to early Christian times, and such monuments

were distinguished by their having a cross inscribed on them. Their purpose

and meaning, however, seem to have been forgotten ere the time came when

they could be written, though even yet in some such form men continue to

hope to hand down their memory to future times. There is no difficulty in

supposing that many of our Scottish monuments are sepulchral and may mark

the last resting place of the most illustrious of the early heroes and

missionaries, and it is easy to understand how others would wish to be laid

near the same spot, and how they would be chosen as fit sites for the

churches, and those in Easter Ross followed this rule.

The labour bestowed on the ornamentation of these stones, and especially on

the crosses, is quite remarkable, and some would attribute it to Roman

civilization from which so much of medimval art must have derived an

impression. But if the symbols could have been derived from this source, it

is difficult to explain why other countries open to the same influence do

not have them. If the symbols are Christian, it seems strange that they are

not found in other parts of Christendom as well as in the north-east of

Scotland. The only inference open is that most of the symbols were peculiar

to a people in the north-east of Scotland and were used by them at least

partly for sepulchral monuments. To the question, Whence did the inhabitants

of this district get their symbols? there is no convincing answer.

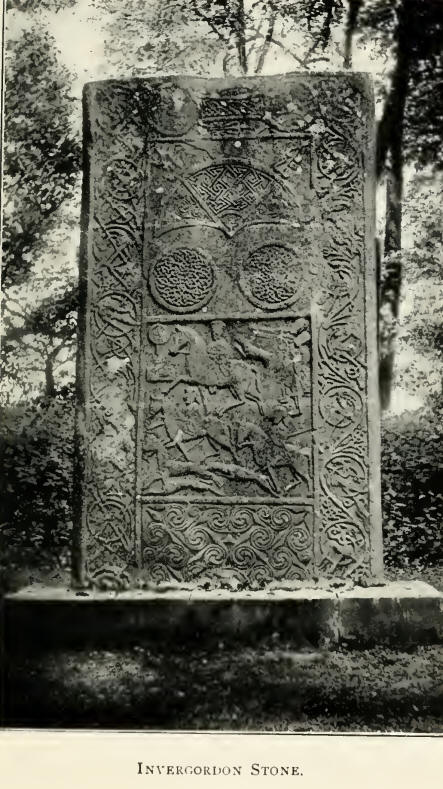

Of the stones in Easter Ross those best known are the Hilton, the Shandwick,

and [the Nigg stones which stood at no great distance from one another. They

are perhaps the most remarkable in Scotland for their elaborate finish and

varied representation. The Hilton stone now in “The American Gardens” at

Invergordon was at some period taken down and converted into a gravestone.

For this purpose one of the sides was smoothed by erasing the ancient

sculpture upon it and the following incription was substituted :—

“He that lives weill dies weil,” says Solomon the wise.

Heir lyes Alexander Duff and his thrie wives.

In this stone the “spectacle” ornament is transferred to the border amid the

ornamental tracery, while two unconnected circles take the usual place on

the face of the stone near the crescent, the whole being filled up with

elaborate tracery. The two figures in the upper corner on the right hand

seem to have been trumpeters. The centre is thickly occupied by the figures

of men, some on horseback, some afoot, of wild and tame animals, musical

instruments, and weapons of war and of the chase.

The Shandwick stone is a magnificent obelisk near the village of Shandwick.

In 1776 it was surrounded at the base by large well-cut flagstones formed

like steps. It was unfortunately blown down in April 1847 and broken, but

soon afterwards it was, by the order of Sir Charles Ross, bound up with iron

and re-erected on its ancient site. It is about eight feet high, four feet

broad, and one foot thick. It has been supposed that the figures on each

side of the cross, immediately beneath the transverse bars are intended to

represent St. Andrew on his cross, but it may be doubted whether they are

not meant to represent angels with displayed wings. Hugh Miller says that it

bears on the side which corresponds to the obliterated surface of the other,

the figure of a large cross, wrought into an involved and intricate species

of fretwork, which seems formed by the twisting of myriads of snakes. In the

spaces of the left side of the shaft, there are huge clumsy looking animals,

the one resembling an elephant, the other a lion; over each of these a St.

Andrew seems leaning forward from the cross, and in the reverse of the

obelisk, the sculpture represents processions, hunting scenes, and combats.

The ground around was for ages used as a burying place, and all unbaptized

infants of the parish were buried here up till fairly recent times. The

ground around is now cultivated.

The exquisitely beautiful Nigg stone now stands under a portico at the east

gable of Nigg Parish Church but it stood near the gate till 1727, when it

was blown down by a blast of wind which also threw down the church belfry.

Towards the end of the eighteenth century it was removed for the purpose of

gaining admission to the vault of the family of Ross of Kindeace, and during

the operation it fell and was broken. It was afterwards bound in iron and

re-erected in its present position. The top of the stone is triangular. On

the one side of this upper compartment are two priestlike figures attired in

long garments, and furnished each with a book. They incline forward as if

intent on reading and devotion. Betwixt them is a small circular table,

which may represent an altar; and above it there is the representation of a

dove in the act of descending to carry away the sacrifice offered. It has a

circular cake in its bill.

Under the table, two dogs of

large size seem restrained by the priestly incantations of the human figures

from executing their evil intentions. Under the triangular top and on the

same side the surface contains the figure of a cross beset by serpents. The

spaces above and below the arms are divided into rectangular compartments of

mathematical exact ness. On the other side the centre is occupied by the

figure of a man attired in long garments, caressing a fawn, and directly

fronting him, there are the figures of a lamb and a harp. The appearance of

the chalice and host between the kneeling figures at the top is very

remarkable. None of the symbols occur on this stone.

Casts of this stone are to be seen in Edinburgh, London, Dublin, and in

several Continental museums.

There are fragments of a stone in the churchyard of Tarbat which formed

parts of a cross which stood in the centre of the churchyard. It was however

knocked down long ago by the gravedigger and broken up for gravestones.

There is a sculptured sarcophagus in the churchyard of Kincardine. The

statistical account says “In the churchyard there is a stone about five feet

in length, and two in breadth and thickness; it is hollow and divided into

two cells. The ends and one of the sides are covered with carved figures and

hieroglyphics.”

In the churchyard of Edderton there is a stone on each side of which is a

carved cross and below one of them is the figure of a man on horseback. In

the compartment below this are two horses with their riders lined out. About

a mile to the west of the Church at Edderton is an obelisk of rough unhewn

whinstone which has a fish sculptured on the north side, and below that two

concentric circles. There is a tradition that a bat-tle was fought in this

place betwixt the inhabitants of the country and Norwegian pirates and that

the leader of the invaders—Carius—was slain and interred here, and hence the

name Carrieblair.

There is, or rather was, a complete chain of dunes or brochs surrounding the

parish of Edderton but the most complete of them Dunalliscaig was completely

destroyed about 1818 and the material of which it consisted was used for

building dykes and farm houses in Easter Fearn. There is little doubt that

many of these once existed in the district but were used up by utilitarian

farmers or proprietors in the same way.

Investigators are now all but agreed that these carved stones could not have

been the work of the Norsemen, as Hugh Miller contends. As most of them are

found in the district once called Pictland, and scarcely anything like them

in other parts where the Norsemen held sway, it is fair to assume that they

were the work of these Picts. As to when they were erected evidence points

to the eighth century as the most probable period. |