|

If that district which has

little history is to be considered happy then this is one of the happiest of

spots, as there are records of wonderfully few of those happenings which are

considered history, civil or uncivil, but much could be written of the ebb

and flow of the many ecclesiastical or religious waves by which for

centuries the district has been swept.

According to Ptolemy, a tribe called the Decanbae lived in the district

which extends from Beauly to Edderton, and the Smertae occupied the valleys

of the Carron, Oykell, and Shin. At a later period the inhabitants of the

district were known as Picts, who probably mixed with Celts. When the

Norsemen came to the west coast they probably drove the Scots eastward and

thus there is some likelihood that in the dim past there was a time when the

inhabitants spoke Pictish, Gaelic, and Norse. Before the opening of the

tenth century the Norsemen were all-powerful in the district and held sway

for about two hundred years.

When their power waned at the opening of the twelfth century the Gaels were

triumphant and the Picts a lost race. Of the feuds for mastery between these

races not a trace seems to remain in authentic history or local tradition

and really nothing can be affirmed of it until it was formally annexed to

the kingdom of Scotland, and then for a long time its history is associated

with Tain, its capital, which received from Malcolm Canmore its first

charter somewhere about 1060 a.d. There still exists in the Tain Council

Chambers a notarial certified copy made in 1564, of the Royal Charter

granted in 1457 by James II., who in it confirms the grants made by his

predecessors, “To God, the blessed St. Duthus, the church and clergy, the

town of Tain and its inhabitants, the immunities granted them within the

four corner crosses placed about the bounds of Tain and all their liberties

and privileges.”

Probably it was by Malcolm that the right of “Sanctuary” was conferred on

the town, a right which must have helped the place into prominence all over

the north as to it in lawless times the weaker could go and be safe from

their oppressors. It is quite possible that this right was got from

Malcolm^and his proselytising superstitious Queen Margaret by Duthack or

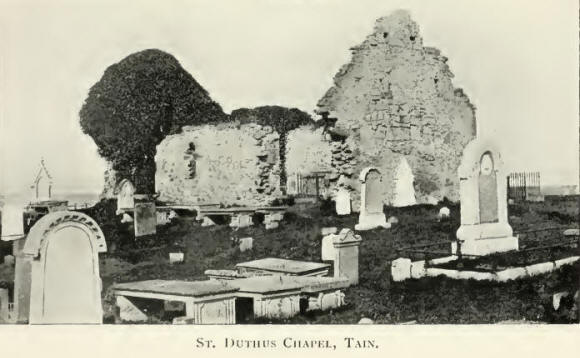

Duthus, afterwards St. Duthus, who is said to have been born in the now

ruined ivy covered chapel near the railway station and who by that time had

somehow acquired his saintly character. The king would very likely hold

Duthus in awe and readily grant the request if he were told that a smith,

when Duthus as a boy came to him for fire, placed some live coals in his lap

arid that the lad carried them home without injury to himself or his

clothes, and that angels were seen encamping around his home at the Angel’s

Hill. St. Duthus studied in Ireland, probably travelled as a missionary, and

died in Armagh in 1065. To this spot nearly two hundred years afterwards his

remains were carried and in this way the holiness of this sanctuary was

further enhanced. So sacred was this sanctuary held all over Scotland, that

in 1306, when Robert the Bruce’s fortunes were at their lowest ebb, he sent

his queen and daughter here with several ladies and a number of knights.

William, the fourth Earl of Ross, unscrupulously violated the sanctuary,

slew the knights, and delivered the ladies up to their English enemies.

Its sanctuary was next violated in 1427 when Mowat, a laird of Freswickin

Caithness, was defeated by Thomas Macneil of Creich. The vanquished fled

here for refuge, but the angry pursuers slew all whom they found outside and

then set fire to the chapel and so brought death to their enemies within and

an end to the building, which has never since been roofed. According to some

authorities important documents placed here for safety were also burnt,

perhaps also St. Duthus’ shirt, a relic which was said to possess marvellous

powers, but did not preserve Hugh, the fifth Earl of Ross, from fatal wounds

though he wore it at the battle of Halidon Hill in 1333. The English, who

likely enough regarded the relic with awe, restored it to the sanctuary.

To the chaplain of this shrine, Janies IV. ordered an annual sum to be paid

that masses might be said on behalf of his father’s soul, while he himself

did penance by wearing an iron chain to which he added a link year by year,

and came here on penance intent sometimes thrice a year for nineteen

successive years, that is from 1494 to 1513. During these journeys he would

doubtless learn to take an interest in the Highlands, would probably hear

complaints of injustice and help to maintain justice. He was here for the

last time on 5th August 1513, and on 9th September following he fell at

Flodden.

In 1483, William, Lord Crichton, took refuge within this “girth” of Tain,

and though verbally summoned by the King’s macer to come to Edinburgh, he

refused to leave it and lived here in safety for some time.

Much of the subsequent history of Tain and Easter Ross is connected with the

struggle of the various creeds and churches for mastery, and some of these

are detailed in the next chapter, but several other historical incidents are

worthy of note. For many a long year the Earls of Ross and other great folk

really held kingly sway and were very pleasant masters for their subjects so

long as they had their own way, but woe betide any who turned on them. It is

told, and though the story may be apocryphal it is illustrative, that when

an injured woman complained to an Earl of Ross, then said to be resident at

Balnagown, that she would go to the king for redress he ordered horseshoes

to be nailed to the soles of her feet that she might be better able to

perform the journey.

Among others who for a time had an interest in Easter Ross was “The Wolf of

Badenoch,” who married a Countess of Ross, and received a Royal charter of

his wife’s lands.

There are also records of clan battles. There was one fought at Alt Charrais

in i486 or 1487 between John, Earl of Sutherland, and Alexander the Sixth of

Balnagown. The occasion was revenge. One Angus Mackay, the son of Neil Vass

Mackay, had been previously slain at Tarbat; a son of the slain man begged

the Earl of Sutherland for assistance so that he might be revenged for his

father’s death. The Earl yielded and sent his uncle, Robert Sutherland, with

a company of chosen men to assist Mackay. Strathoykell was invaded with fire

and sword, and there was “burnt, spoiled, and wasted many lands appertaining

to the Rosses. The laird of Balnagown, hearing of this invasion, gathered

all the forces of the province of Ross, and met Robert Sutherland and John

Mackay at Alt Charrais. There ensued a cruel battle, which continued a long

space with incredible obstinacy; the doubt of the victory being no less

great than the desire. Much blood was shed. In the end, the inhabitants of

Ross, being unable to endure the enemy’s force were utterly disbanded and

put to flight. Alexander Ross of Balnagown was there slain with seventeen

other landed gentlemen of the province of Ross, with a great number of

common soldiers.”

Some of the leaders of Easter Ross Society, notably Katherine, the eldest

daughter of the ninth Earl of Balnagown, had resort to witchcraft and

poisoning to accomplish her purposes, and her career is fully and

interestingly set out in Chambers’ Domestic Annals of Scotland, vol. i, pp.

203.

Much interest was excited in

this district in 1626 in connection with the thirty years’ war, and a

regiment was raised here to fight under Gustavus Adolphus. It is worthy of

note that in these German wars under this Lion of the North, there were

engaged three generals, eight colonels, five lieutenant-colonels, eleven

majors, and more than thirty captains, besides a large number of subalterns

of the name of Munro.

The Twelfth Ross of Balnagown, at his own expense, raised a regiment of

Rosses to help Charles II., and proceeded with the Scots to England, where

they were defeated at Worcester. Eight thousand prisoners were taken, and

among them many Easter Ross men who were sold as slaves to the American

Colonists. The laird himself was imprisoned in the Tower and died in 1653.

It is pleasing to have to record that after the Restoration this king

settled a pension on Balnagown’s son.

That was not the only connection Easter Ross had with the fight between

Cromwell and the Royalists, and the following account of how Lieut.-Colonel

Strachan outwitted the celebrated Marquis of Montrose on the borders of

Sutherland and Ross is of interest.

The Marquis crossed from Orkney to Caithness in April 1650. He had

calculated on collecting a considerable force in that county, but failed. He

marched southwards, and the Earl of Sutherland retired before him as he

advanced and Montrose reached Strath Oykell with but a force of 1200 men.

Lieut.-Colonel Strachan hurried to meet him with a party of horse, while

Leslie was pressing on with 3000 foot. It was resolved that the Earl should

cross into Sutherland to intercept Montrose’s retreat, while Strachan

advanced with 230 horse and 170 foot in search of him. Under cover of some

broom, they succeeded in surprising him at a disadvantage, on level ground

near a pass called Invercharron, on the borders of the parish, on Saturday,

27th April 1650, having diverted his attention by the display of merely a

small body of horse. Montrose immediately endeavoured to reach a wood and

craggy hill at a short distance in his rear with his infantry, but they were

overtaken. The Orkney men made but little resistance, and the Germans

surrendered, but the few Scottish soldiers fought bravely. Many gallant

cavaliers were made prisoners, and when the day was irretrievably lost, the

Marquis threw off his cloak bearing the star, and afterwards changed clothes

with a Highland kern that he might effect his escape. He swam across the

Kyle, directed his flight up Strath Oykell, and lay for three days concealed

among the wilds of Assynt. At length, exhausted with fatigue and hunger he

was apprehended by Neil Macleod, who happened to be out in search of him.

The gallant Marquis’ subsequent fate is well known.

As in other parts of the north the people of this district were much

agitated by “The Fifteen,” though they seem almost unanimously to have sided

with the Hanoverians. Sir Robert Munro asked Lord Strathnaver to assist him

to defend Ross-shire. This he did, and at the same time the Munroes, Grants,

and Rosses were mustered by their chiefs. When the Earl of Seaforth, who

favoured the Jacobites, asked Sir Robert to deliver up all his defensive

weapons, he refused, garrisoned his house, and sent men to the rendezvous at

Alness. But Lord Duffus, with Seatorth not far away, marched into Tain with

between 400 and 500 men of the Mackenzies, Chisholms, and Macdonalds,

proclaimed James there, and then made haste south to join the Earl of Mar.

The Easter Ross men who stood by the Government were in 1716 gathered at

Fearn to the number of 700, ready to march to Inverness but they had to

complain of the scarcity of provisions. So scarce indeed was meal then in

this district, that the people were starving. This regiment was soon

afterwards disbanded.

In “The Forty-five” Easter Ross men, with the exception of the Earl of

Cromartie and his son, Lord Macleod, again seem to have favoured the

government and some of them were at Prestonpans and Falkirk. Tain was during

this time subjected to great distress and oppression from a large body of

Jacobites quartering there and making arbitrary demands for money, and the

magistrates were forced to make large payments. The Earl of Cromartie raised

400 men and with his son (then a lad of eighteen), marched to join the

Pretender’s army and they fought—possibly against other Ross-shire men at

Falkirk. Subsequently tbe Earl held the chief command north of the Beauly,

but was on 15th April 1746, surprised and defeated near Dunrobin Castle

where he was captured on the eve of Culloden. For this, both father and son

were sentenced to death, but by the strenuous and good offices of Sir John

Gordon, the second Baronet of Invergordon, they were afterwards pardoned.

This Lord Macleod, after distinguished service in India, succeeded to the

estates of his influential uncle in 1783, and had his family estates

restored to him in 1894. It was he who sold the Invergordon estates to

Macleod of Cadboll.

So far the history of Easter Ross, like that of most other parts, has simply

been the story of the fighting of chieftains or their superiors for

supremacy but the condition of the people, as Hallam says, “like many others

relating to the progress of society is a very obscure inquiry. We can trace

the pedigrees of princes, fill up the catalogue of towns besieged and

provinces desolated, describe the whole pageantry of coronations and

festivals, but we cannot recover the genuine history of mankind. It has

passed away with slight and partial notice by contemporary writers, and our

most patient industry can hardly at present put together enough of the

fragments to suggest a tolerably clear representation of ancient manners and

social life.”

“The Forty-five altered the relation of the people to their chiefs and the

relation was afterwards in many cases a purely commercial one as between

landlord and tenant, and of course the former were naturally anxious to get

the highest possible rent for their lands. Farming in this fertile machair

was as yet carried on in primitive fashion but improvements were being

inaugurated and better crops were being got, but when it was found on the

Borders that the hills and dales yielded most profit when improved breeds of

sheep were reared, and that a sheep farmer from the southern dales offered a

rent of £350 for a sheiling in Glengarry for which others paid only £15 the

temptation to most landlords was irresistible. Though it involved hardship

to the natives they were not allowed to stand in the way and in 1763 the

laird of Balnagown took the initiative and after some experimenting, he in

1781 offered a farm to a Mr Geddes who is believed to have been the first

sheep farmer in the north of Scotland. The people saw themselves deprived of

their holdings for sheep and gave the farmer all the annoyance they could.

They shot or drowned many of his sheep but yet Mr Geddes was able to pay his

rent and grow rich though the seasons were bad enough. In 1782-83 the crops

were an entire failure over the whole Highlands. So hard pressed were the

tenantry that a gathering of lairds and their factors was held in Tain on

10th December 1783 I in order to take into consideration the state of the

tenantry in that part of the country and to form some plan whereby they

might convey some effectual relief to their distressed situation.” The

minutes of the meeting at which Donald Macleod of Geanies presided say, “the

gentlemen present having taken the state of the country into their serious

consideration, and having maturely and deliberately reasoned thereon, they

were unanimously of opinion that the situation of the whole of this country

is extremely critical, and that if severe and harsh means are adopted by the

proprietors of Estates in forcing payment of arrears at this time, though

the conversion should be at a low rate, it must have the effect of driving

the tenantry into despondency, and bring a great majority of them to

immediate and inevitable ruin ; and in so doing will go near to lay the

country waste, which to the personal knowledge of this meeting, has been for

these two hundred years back over-rented ; and if once the present set of

tenantry are removed, there will be very little probability of getting them

replaced from any other country.”

For all this the people continued to feel the pinch of poverty and Sir

George Mackenzie said that they were prejudiced against “improvements,” as

the formation of sheep farms was called. At last in the Autumn of 1792 men

were despatched to make public proclamation at all the churches in Ross and

Sutherland that the hated sheep were to be gathered and driven across the

Beauly. In response the people began at Lairg and drove before them every

sheep they could find in Lairg, Creich, and Kincardine. In four days they

had thousands of sheep driven out of Easter Ross as far as Alness. Here the

drovers were met by the sheriff accompanied by Sir Hector Munro of Novar and

a party of the 42nd Regiment which had made forced marches from Fort George.

At sight of the soldiers the drovers fled. Several of them were caught,

tried at Inverness, and had heavy sentences passed on them, but they soon

escaped from prison. General Stewart of Garth says, It would appear that

though the legality of the verdict and sentence could not be questioned,

these did not carry along with them public opinion, which was probably the

cause that the escape of the prisoners was in a manner connived at; for they

disappeared out of the prison, no one knew how, and were never inquired

after or molested.”

For some time after this things went on quietly, notwithstanding the

hardships endured by the failure of the crops in 1808 and 1818, until in

1820 Munro of Novar resolved to remove the Culrain tenantry to the number of

between two and three hundred. The tenantry knowing that they owed him no

rent, resolved to retain their holdings. They therefore resisted the

officers employed to serve the summons of removal. In order to enforce the

execution of the writs the sheriff of the county went to Culrain accompanied

by twenty-five soldiers and a body of gentlemen from Easter Ross. On

approaching Culrain the progress of the party was interrupted by the

appearance of a crowd of between three and four hundred people, chiefly

women, and men in women’s clothes, who rushed on the soldiers, attacked them

with sticks, stones, and other missiles and compelled them to retreat. The

soldiers fired several rounds of blank cartridge but the people were not

terrified. Then one of the party used a ball cartridge by which one woman

was fatally, and one or two less seriously, injured. Of course the “civil”

power was in the end victorious and this “improvement” also was effected at

Culrain. Small landholders were thereafter gradually removed in several

other districts and the fertile large farms of Easter Ross formed.

In the New Statistical Account the ministers of Kilmuir Easter, Nigg, Logie

Easter, Rosskeen, and Kincardine comment on the result. He of Kilmuir says,

“The great evil which requires to be remedied in some way or other is the

fluctuating state of the population in consequence of the arable land being

in the possesion of a few, which, however much it may tend to the

agricultural improvement of the parish, certainly is not calculated to

improve the state of the population. In consequence of this many of the

people are always on the wing, and shifting from one parish to another, in

quest of a better place or of more congenial employment; thus rendering in a

great measure migratory the instruction which they receive.”

Since then things had to be adjusted after the passing of the Corn Laws but

the farms have increased in fertility so that now it can truly be said that

life has little better to offer than the lot of an Easter Ross farmer, while

the lot of the farm servants has been ameliorated in many directions.

Probably nothing affected the progress of the people so much as the making

of roads which were begun to be seriously made when the provisions of the

Statute Service Road Act of 1720 were adopted and bye laws made for

enforcing the Statute Labour Act or commuting it by money payments. The

greatest step in this direction was the making of the parliamentary road

from Perth to Wick, completed in 1821, and which effectually linkedthe

district to the rest of Scotland. In 1809 a “Diligence” began to run from

Inverness to Tain on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, and from Tain to

Inverness on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. Much was made of the fact

that the 44 miles could be covered in one day. The upkeep of these roads was

so heavy that toll-bars were placed here and there along the route and were

certainly bars to progress until the Ross and Cromarty Act of 1866 abolished

therm and now the roads in the district are as good as any in Scotland.

The railway was opened to Invergordon in 1863 and to Bonar-Bridge in 1864. |