|

IT may not be uninteresting here to say a few words about the town and

trade of Tihicoultry, which has now for so long a period been the place of

my abode.

There is an old story told of how Tillicoultry got its name,

and it really has 'the ring' of probability about it. A Highlandman was

taking a drove of cattle along the old road, and when passing through

Tillicoultry Burn, none of the cattle took a drink, when, in astonishment,

he exclaimed, 'There's Tiel a coo try' (Deil a cow dry), in Tonald's way

of pronouncing the D; and hence the town, it is said, got its name.

However, the writers of both the Statistical Accounts of Scotland say that

the etymology of the word is purely Celtic, and is composed of three

words— Tullic/-Cul-tir, and signifies 'The mount or hill at the back of

the country;' or, as a Gaelic correspondent puts it, 'The hill behind the

stretch of land.' The Rev. William Osborn (the writer of the first

Statistical Account) suggests the possibility of the name being derived

from the Latin words Tell'us cula, 'The cultivated land.'

We learn from

that interesting little book, Tillicoultry in Olden Times (by Mr. Watson,

headmaster of our public school here, and published by Mr. Roxburgh of the

Tillicoultry News office, price sixpence), that the

estate of Tillicoultry was granted to the family of Mar in 1261, the

fourteenth year of the reign of Alexander the Third; and from that very

early date to the present day it has passed through the hands of no fewer

than eleven proprietors,—Lord Colville of Culross and the Earl of Stirling

being amongst the number,—until in 1814 it came into the hands of R.

Wardlaw Ramsay, Esq., the father of the present proprietor, and in 1840

into the possession of' his son, the present laird—Robert Balfour Wardlaw

Ramsay, Esq., who is also proprietor of the fine estate of Whitehill, near

Edinburgh. The Kirk Hill, or Cunningham Hill,

which begins at the Devon, and goes up to near Tillicoultry House, and on

the south end of which our beautiful cemetery has been formed, is to the

antiquarian, the most interesting part of the estate. Immediately opposite

the cemetery lodge, on the north side of the public road, and close to it,

a large portion of a druidical circle can still be seen, of about 130 feet

in diameter, which (but for the Vandalism of some modern builder, as Mr.

Watson informs us) might have been one of the most interesting sights in

Scotland. A number of old druidical stones, five and a half feet high,

stood at one time in the circle, but by this Goth of a fellow had been

removed (very probably to build a dyke with). Had these still remained,

the true nature of the place would have been apparent at a glance. Now,

however, it is difficult to tell what it has been; and but for the old

Statistical Account of Scotland (from which Mr. Watson got his

information), people would have been a little incredulous as to the true

nature of the place.

The same Vandalism is—in

this nineteenth century of ours----still going on; for this famous old

relic of antiquity is being gradually carted away in the shape of sand—the

one half of it having already disappeared into the great sand. pit

adjoining. Had the present proprietor resided at Tillicoultry instead of

Whitehill, this surely would never have been allowed to go on.

From several urns containing human bones having been

dug up at the north end of the Cunninghar Hill, it is supposed the Romans

had a station here; and an old rusty sword, evidently of Roman make, was

dug up a little farther east, near to Harviestoun Castle.

In early days there were three villages in the parish

of Tillicoultry—Eastertown, Westertown, and Coalsnaughton. Harvieston Burn

ran through the centre of Eastertown; and that portion of the village on

the west side of the burn was called Ellieston, while that on the east

side was called Harviestoun. It was situated above the present road on the

north side of the Castle, and close to where the home farm now is. It was,

in early times, larger than Westertown, although not a vestige of it now

remains. It was entirely removed by Mr. Tait when he formed the garden for

Harviestoun Castle, on the site of which it stood. The road from

Eastertown to Dollar was by Whitehilihead, and joining the old highway at

the villa of Belmont. Mr. Andrew Rutherford, of the post office, Dollar,

is a native of Ellieston, and attended the school in Tillicoultry when a

boy. Tillicoultry—as at present—is Westertown

very much enlarged; and the old church, manse, and churchyard were

situated between the two, close to Tillicoultry House. The first manse on

the present site was built in 1730; the first church on the present site

in 1773; and the present handsome building in 1829.

A curious legend is told about the old churchyard of

Tillicoultry, which is situated at the back of the mansion house. A wicked

laird quarrelled with one of the monks of Cambuskenneth, and in the heat

and excitement of the moment actually knocked the holy father down. Dying

shortly after this, it was discovered next morning after the funeral, that

the wicked clenched fist that dealt the sacrilegious blow was projecting

out of the grave, and it was looked upon as a punishment sent upon him

from heaven for his wicked conduct. However, as this couldn't be allowed

to remain, the grave was opened and the hand replaced in it, and an end,

it was thought, put to the dreadful apparition. What, then, was the good

folks' surprise, on paying a visit to the grave on the following morning,

to find the terrible hand up again. This was repeated day after day for a

whole week, till the people were getting into an alarming state of

excitement and terror. As a last resource, however, an immense stone was

brought and placed over the grave, and now the hand no longer appeared.

This stone was too heavy for the monks to roll away, and repeat the

imposition they had evidently been practising upon these simple-minded and

superstitious folks; and hence the hand now got rest. This legend gave

rise to the old Scotch saying, when any one had given a blow, 'Your

hand'II wag abune the grave for this yet.' This big stone, which proved

'one too many' for the monks, is still pointed out in the old churchyard.

(For other information about Tillicoultry in days of old, see Mr. Watson's

very interesting little book.)

The population

of Tillicoultry parish was-

On the west side of the burn, and overtopping the

village, stands the beautiful Castle Craig, wooded to the top, and on

which stood, in ancient times, a round Pictish fortress, the traces of

which can still be distinctly seen. This craig is, I think, one of the

most picturesque objects on the Alva estate, and it is a very great pity

that it should be so disfigured by the extensive quarrying operations that

are being at present carried on at it. Not far from the foot of this craig,

and on the same site where Castle Mills dwelling-house now stands, an old

castle stood, in the beginning of this century, inhabited by two old

maiden ladies—Misses Kirkwood —of whom Mr. Edward Moir has a distinct

recollection. It was afterwards occupied by one Thomas Harrower, who

manufactured 'a drop of the cratur' on his own account; and the excise

officers, getting to hear of this, surrounded the castle, and summoned

Thomas to surrender; but he was deaf to all entreaties, and would not open

the great old door (full of large-headed nails) to them. Recourse was then

had, therefore, to force, and a supply of large forehammers procured from

a smithy down the village, and with these the big old door was soon

hammered to pieces, the sound of the knocks being distinctly heard in Mr.

Moir's dwelling-house, a long way from the castle. It would be either from

this old castle, or the Pictish fortress on the top of the craig, that

Castle Craig got its name; but from which, it is not easy now to say. A

little below this castle, a meal-mill was carried on in those days by a

man named William Carmichael, but it has long since entirely disappeared.

Its site was where the entrance gate now is.

About twenty-five years ago, the damhead or reservoir for the public works

of Tillicoultry (erected in 1824) stood a little above the quarry, at the

very mouth of the glen; but as it was getting old, and a new one required,

a much more suitable site was fixed on for it, about a quarter of a mile

back the glen, and the present dam- head was then built. Our late worthy

townsman, Mr. Graham Paterson, was the architect and builder of it, and a

most substantial job he made of it. The getting up of the, enormous logs

required in its construction proved a very formidable undertaking, and

attracted a great amount of attention and curiosity. A carriage had to be

specially made for the. purpose, and on it they were dragged up the sledge

road, entering by the gate near the Wood Burn, a number of horses being

required in the operation. It was erected in 1853-1854, and cost £515.

The damhead is situated in a very romantic part of the

glen, and is well worthy of a visit. Indeed, the whole glen, up to the

base of Ben Oleugh, is rocky, precipitous, and wild, and would quite

compare with some of the finest Highland scenery, and one could almost

imagine himself in the midst of the Grampians. The hills immediately

behind Tillicoultry are—the Miller Hill, to the west of the burn;

adjoining it, on the west, is the beautiful Wood Hill, on which the

mansion- house of James Johnston, Esq. of Alva, stands; the Law, between

the two branches of Tillicoultry Burn; Ben Cleugh (the highest hill of the

Ochil range-2363 feet high) is immediately behind the Law; the Whum and

Andrew Ganhill are to the east of the Law; and immediately beyond them is

Maddy-Moss. The hill above Tillicoultry, on the east side of the burn, is

called Tillicoultry Hill. The one between Tillicoultry House Burn (or

'Back Burn') and Harviestoun Burn, is Ellieston Hill—the east half of

which is in Harviestoun estate, and the west half in that of Tillicoultry—the

stone dyke which separates the two properties running up the centre of it.

The hills on the east side of Harviestoun Burn are, the Grains Hill,

Harviestoun Hill, and Dollar Bank Hill - all three terminating in the

farther back and second highest peak of the Ochils, the King's Seat.

Tillicoultry Burn, and the other streams of the Ochils

utilized for water-power, have been rendered of very much less value to

the millowners than they used to be, from the extensive system of drainage

that has been carried on for the last thirty years all over the Ochil

range. Previous to this, the extensive morasses that exist on the hills

used to act as natural reservoirs; and after a heavy rain, good full water

was experienced for several weeks. Now, with the deep drains that

intersect these places in all directions, the greater part of the water

rushes off as fast as it falls, and in two or three days after a flood the

streams are as small as ever. In consequence of this, the water-power of

our burns has become of very little value indeed, and but for the aid of

steam we would be helpless. Helen's Muir, on the back of Tillicoultiy

Hill, is a fine example of this extensive system of drainage some of the

main drains being of great depth and very wide.

The wire fence that separates the Alva from the

Tillicoultry estates runs right up the centre of the Law, and passes

within a few feet of the cairn of stones on the top of it; whilst that

which separates Tillicoultry from Harviestoun estates, runs up Harviestoun

Glen; and both join the one from Maddy-Moss to Ben Cleugh, which is the

southern boundary of Back Hill farm. The top and south side of Ben Cleugh

are in Alva estate; part of the Law, the Whum, and Andrew Ganhill, are in

Tillicoultry estate; while the King's Seat is in Harviestoun estate. Back

Hill farm—which extends back to Devon, with Broich for its eastern

boundary, and Greenhorn for its western—is in Tillicoultry estate.

On a clear day, the view from the top of Ben Cleugh is

very grand, embracing as it does not only the wide Ochil range, stretching

in all directions a long way below you, but an extensive view also of

Strathearn and the hills beyond Crieff; while to the south, the river

Forth, with all the beautiful scenery surrounding it, forms one of the

finest panoramas that could be seen anywhere, perhaps, in the British

Isles. Benlomond and all the western hills are embraced in the beautiful

prospect; while away to the east, the Bass Rock and the mouth of the Firth

of Forth can be distinctly seen. The view from Craigleith Hill above Alva,

and from Damyat to the west of Menstrie, is also very fine. The latter

stands out a little from the rest of the range, and commands a beautiful

view of the Devon valley.

The Abbey Craig, on

which the Wallace Monument stands, is a rocky spur of the Ochils, and is

situated between Logic and Bridge of Allan, and stands out a good way in

front of the range. No finer situation could have been selected far this

monument to our old Scottish hero, as it is seen from a very great

distance in all directions.

From the remains of old turf walls and stone dykes that

cover the Ochils in our neighbourhood, it seems very clear that they were

at one time possessed by a great many proprietors, and not, as at present,

in the hands of two or three. One of these turf walls can be seen,

extending from the Mill Glen House to the Wood Burn, and going right over

the top of the Miller Hill. That patches of the very tops of the hills,

also, had been at one time under the plough, can be distinctly seen on the

level plateau on the top of this hill, the deep furrows being quite

visible from one side of it to the other.

In

the end of last century, a Mr. John Cairns (the late Laird Cairns'

grandfather) lived in this Mill Glen House, where there had been a

considerable sized farmsteading—the foundations of the houses being still

distinctly seen, and the form of the garden easily traced. The sledge road

would be made for the use of the dwellers in this hill farm. The burn that

runs past this house was then called Tankley Burn, but it now generally

gets the name of the Mill Glen House Burn. Mr. Edward Moir has a distinct

recollection of the last inhabitant of this house; but he had left it

before his day, and was residing in Tillicoultry.

In the old Statistical Account of Tillicoultry, Mr.

Osborne says: 'There are many veins of copper in the hills. Some of these

were wrought near fifty years ago (about the years 1740 to 1745) to a very

considerable extent in the Mill Glen. Four different kinds of copper ore

were discovered, the thickest vein of which was about 18 inches. The ore,

when washed and dressed, was valued at £50 sterling per ton. A company of

gentlemen in London were the tacksmen, and for several years employed

about fifty men. After a very great sum of money was expended, the works

were abandoned, as unable to defray the expense. Ironstone, of an

exceeding good quality, has been found in many different places.' Some

veins in Watty-Glen are as rich as any discovered in Scotland. Besides

copper, there is a great appearance in the hills of different minerals,

such as silver, lead, cobalt, antimony, sulphur, and arsenic, but no

proper trials have yet been made.'

'The whole

parish, south of the hills, abounds with coal. . . . There are four

different seams. The first, 3 feet thick, 12 fathoms from the surface. The

second, 6 feet thick, 15 fathoms deep. The third, 2 j feet thick, 20

fathoms deep; and the fourth is about 5 feet thick, and 30 fathoms deep.'

Mr. Watson, in his interesting little book, says: 'On

the west side of the Mill-Glen are hard grey basaltic rocks, and on the

east side, a species of red granite capable of taking a polish. . . . The

presence of silver in the Ochils is well known from the history of the

famous silver mine on the Alva estate, from which for thirteen or fourteen

weeks ore to the value of £4000 per week was extracted by the proprietor,

Sir John Erskine of Alva.' The glen where this mine was situated still

goes by the name of the Silver Glen. It is right above Burnside of Alva.

The late Robert Bald, Esq., of Alloa, in his valuable

contribution on 'Geology and Mineralogy,' to the Statistical Account of

Alloa Parish in 1840, says in regard to the collieries: 'The coals of this

parish have been wrought for a long period of years, but at what time they

commenced is quite uncertain. It would appear, however, from some very old

papers in possession of the family of Mar, that coals were wrought

previous to the year 1650 by day-levels.

'The

stratification has been satisfactorily proved to the depth of 140 fathoms,

extending beyond the lowest workable seam of coal in the field. . . . The

number of seams of coal found in the depth of 115 fathoms is twenty-one,

the aggregate thickness of which is fully 60 feet. At the present time, no

coal here is reckoned workable to profit below 2 feet thick. If all the

coals below that thickness are deducted, there remain nine workable coals,

the thinnest of which is 2 feet 8 inches thick, and from that to 9 feet. .

. . Of the thin coals in this parish some of them are only an inch or two

thick. . . . Until within these thirty years, all the coals in this parish

were brought from the wall face or foreheads of the mines by women,

married and unmarried, old and young; these were known by the name of

bearers. When the pit was deep, they brought the coals to the pit-bottom;

but when the pits did not exceed 18 fathoms, they carried the coals to the

bank at the pit-head by a stair. A stout woman carried in general from one

hundred to two hundredweight, and, in a trial of strength, three

hundredweight imperial.'

'As the collieries in

this parish extended, this oppressive slavery became evidently worse, and

the late most worthy and excellent John Francis, Earl of Mar, with a

benevolence and philanthropy which does honour to his memory, ordered this

system to be completely abolished. The evils attending this system may in

some degree be estimated, when it is stated that, when his lordship put an

end to it, 50,000 tons of coals were raised at his collieries annually,

every ounce of which was carried by women.)

This system of carrying the coals was still in existence at Dollar in my

young days, for I recollect well of watching the poor women toiling up the

long stairs with their heavy loads. The creels were placed on their backs,

and were' supported by a belt put round their foreheads, and in this way

they laboured up the long stairs of 108 feet (18 fathoms) with their

grievous loads of two and three hundredweights. Truly, as Mr. Bald says in

another place, 'of all the slavery under heaven's canopy (the African

slavery as it was in the West Indies excepted), this was the most cruel

and oppressive.'

No range of hills in

Scotland, I believe, possesses a greater number of fine trout-fishing

streams than the Ochils. I will refer first to that one with which I was

earliest acquainted—Dollar Burn. Fine trout used to be got in it (and, I

suppose, will still be) from where it falls into the Devon, up to near the

very top of its two branches—the Bank and Turnpike Burns. From the upper

bridge to a little above the Black Linn, I knew at one time every stream

and pool, and almost every stone in it, and fished this part of the burn

every other night —the fishing-rod and bait being kept always ready.

Considering the number of boys that fished this part of the stream almost

every night in the fishing season, it does seem really surprising how a

single trout was left in it; but there they constantly were, and we seldom

had to go unrewarded. The great flood of 1877 has entirely swept away all

the old landmarks (or rather watermarks) of this part of the burn; and now

the pools and streams which I used to know so well are all entirely gone.

An island which existed just below the wood is now joined to the west side

of the burn—the branch of the burn which formed it (and in which were some

fine fishing pools) being now quite filled up.

The largest and best

fishing stream of the Ochils is, of course, the Devon; to which all the

others on the south side of the range, west of Muckart, are tributaries.

Rising in the midst of the Ochils, on the back of Craighorn Hill, right

north from Alva, the Devon falls into the Forth at Cambus, only a few

miles from its source, after a run of about thirty miles. Its course till

it reaches Kameknowe is almost due east; it then turns southwards, and,

passing through Glendevon, runs almost due south till it comes to the

Crook of Devon (or, 'The Crook,' as it is generally called), where,

turning sharply round, it then runs straight west till it passes Menstrie;

and after a short run southwards again, it joins our

noble river, the Forth, at Cambus. From Back Hill House to Dollar, no

finer trout-fishing ground could be found anywhere than on the Devon. The

fine scenery on this stream at Glendevon, the Black Linn, the Rumbling

Bridge, and Caldron Linn, is so well known, I will not attempt to describe

it. I would merely say to all those who have not seen those celebrated

places, they should embrace the first opportunity that comes in their way

of doing so, and I am sure they will not be disappointed.

The farthest-up tributary of the Devon that I have

fished is the Greenhorn, which rises on the west shoulder of Ben Cleugh,

and runs northwards (passing Alva Moss) into the Devon. The next in order

is Broich, which rises at Maddy-Moss, and, after a run northwards of about

three miles, joins the Devon at Back Hill House. Grodwell (a fine branch

of T3roich) rises on the back of Ben Cleugh, and joins the larger stream

about a mile north from Maddy-Moss. We come next to Frandy Burn, and then

Glensherup, both fine fishing streams. It is on the latter the reservoir

for Dunfermline waterworks has been constructed. The next tributary is

Glenquhey Burn, with its fine branch the Garthiand. This, I believe, is

the most severely fished stream of any in the Ochils, being within a

convenient distance of Dollar, with its large population of boys. After

passing Dollar, we then come to Tillicoultry Burn, with its two branches —Daiglen

and Gannel Burns—which would have plenty of trout but for being so

constantly fished. Some good trout are occasionally got in the linus in

the glen. The next in order are Alva and Menstrie Burns, neither of which

I have fished, but which, I have no doubt, would, like the others, have

plenty of trout if they could only get a little rest. There are an immense

number of smaller streams all the way round, but none of which are big

enough to tempt the angler, although I have no doubt many of them contain

trout. On the north side of the Ochils, the

stream corresponding to the Devon on the south side is the Allan. It has

many tributaries from the Ochils—the Wharry, Millstone, Buttergask,

Ogilvie, and Danny Burns, the last joining it at Blackford. The Ruthven

and the Water of May are tributaries of the Earn. The highest hill on the

north side of the Ochil range is Craigrossie, to the south-east of

Auchterarder. The north and south Queichs

drain the south side of the eastern portion of the Ochils, and fall into

Lochleven; while the Farg, which rises north from Milnathort, falls into

the Earn, about three miles from where it joins the Tay. The great north

road runs through Glenfarg—one of the most picturesque glens in Scotland.

The greater portion of it is beautifully wooded; while the road, which

follows close to the stream in all its serpentine windings through the

really beautiful, and, at places, narrow glen, presents at every turn

fresh glimpses of magnificent scenery, and forms quite an enchanting

drive. Before the railway from Edinburgh to Perth was formed, the stage

and mail coaches between those two cities ran through Glenfarg, and many

is the time I have passed through it, seated on the top of the 'Defiance.'

In the Statistical Account of Scotland, the Rev. Mr.

OsborRe says, in connection with the hill burns of Tillicoultry: 'No trout

were ever discovered in the Glooming-side Burn (the name then given to

Gannel Burn), though it has plenty of water, and remarkably fine streams

and pools. Trouts have even been put into it, but without the desired

effect. This is supposed to arise from some bed of sulphur, or other

mineral hurtful to fish, over which the burn passes.'

This belief had got so impressed on the minds of the

community, that no one ever thought of fishing in this burn, until, forty

years after Mr. Osborne wrote this Account, this popular fallacy was

discovered by the merest accident. The late Mr. John Ure, and his

brother-in-law Mr. James Archibald (then a boy of 14), started one

morning, in the year 1833, for a day's fishing on the hills, and, the

morning being very misty, they got a little confused as to where they

were. Mr. Ure intended fishing down Greenhorn, and Mr. Archibald down

Grodwell and Broich, and they were to meet on Devon. Under Mr. Ure's

directions, his young brother- in-law got to what he considered was

Grodwell, and hadn't fished long till some excellent trout were caught;

and when he reached what he considered was Broich, he soon got a basket of

large, beautiful trout. After getting well down the burn, he came, to his

surprise, to some impassable rocks, that he never remembered having seen

on Broich before, and was quite puzzled as to where he was. On getting

above the rocks, and pursuing his way a little, what was his astonishment

to find, that in place of landing at Back Hill House, as he expected, the

town of Tillicoultry was lying down below him. The truth then flashed upon

him that he had been fishing all day in Glooming-side Burn (Gannel), which

was popularly believed, for at least forty years, to have had no trout in

it; and here was his basket filled with large, beautiful trout. When Mr.

Ure came home, he could scarcely credit what had taken place, till he

himself, on a subsequent occasion, had verified the truth of it. And now

the secret was out, but was for a considerable time made known only to a

very few. One of those fortunate few, however, came home invariably with

such a well-filled basket, that it quite excited the curiosity and envy of

one of his acquaintances, and he determined that he would watch him some

day when he knew he was going for a day's fishing, and learn the secret.

Accordingly, he started up to the hills one morning before him, and

concealed himself at a convenient spot where he could watch his movements.

What then was his profound surprise when he discovered that he went down

to Gannel Burn. This discovery, as may be supposed, took the whole village

by surprise, and a sorrowful time of it the poor trout had after that, as

a perfect rush of fishers at once took place to the doomed burn, and the

'big ones' quickly disappeared.

TILLICOULTRY A MANUFACTURING VILLAGE IN THE DAYS OF

QUEEN MARY. We learn from Mr. Watson's

interesting book, that as far back as the days of Queen Mary (in the

middle of the sixteenth century) cloth was manufactured in Tillicoultry,

which afterwards became so famous that it established for itself a name

throughout the country, and when other places commenced to make the same

kind of cloth, it had to be sold by the name of the place where it was

first introduced: it was called 'Tillicoultry serge,' and no other name

would take the market ;—in the same way as, at the present day, thousands

of spindles of stocking-yarn are sold annually as 'Aba yarn' that never

saw Alloa. When alluding to the now celebrated

Alloa stocking- yarn, I may, in passing, refer to the very small beginning

of the business at Kilucraigs, which has turned out to be one of the

largest (if not the largest) of the kind in the kingdom. When old Mr.

Paton commenced business, he had only two carding engines; and now the

firm of John Paton, Son, & Co., are possessed of forty- nine sets of

machines (147 carding engines) at their three works at Kilneraigs,

Keiliersbrae, and Clackmannan.

Mr. Watson

tells us that the writer of the old Statistical Account of Scotland

describes the serge 'as being a species of shaloon, having worsted warp

and yarn waft.' The weavers were called 'websters' in those days, and are

mentioned in the oldest records of the kirk-session of Tillicoultry.

With reference to the introduction of this serge into

Tillicoultry, Mr. Watson says: 'What led to its being located here can

only be conjectured. David I. received into his dominions a number of

Flemish refugees, driven in 1155 from England by Henry II., whose policy

thus contrasted unfavourably with that of Henry I., who had gladly given

encouragement to the honest Flemish artisans to settle in his realms. It

is not improbable that the woollen manufacture was introduced into this

part of Scotland by some of these Flemish refugees. Amongst the natural

advantages in its favour may be reckoned the supply of wool which was

obtained from the pastoral lands of the Ochils. When this supply was

insufficient, it was not uncommon for the guidwife to go to Edinburgh for

a stone of wool, which she carried home on her shoulders, and afterwards

spun into yarn in the intervals of her household duties.'

'The cloth was sold at an average price of is. per

yard. . . . It is much to be regretted,' says the Rev. Mr. Osborne (who

was minister of Tillicoultry from 1774 till 1795), 'that more attention is

not paid to the manufacture in the place where it was invented, or at

least brought to the greatest perfection. About fifty years ago, a serge

web from Alva would not sell in the market while one from Tillicoultry

remained unsold. But this is by no means the case at present. The author

of this Account can give no precise statement of the quantity of serge

wrought here, as the stamp- master keeps no list. He supposes, however,

that he stamps annually 7000 ells of serge, and an equal quantity of

plaiding. Some of the weavers are now employed in making muslins; but as

this branch is still in its infancy, it is impossible to say with what

advantage it may be attended.'

It couldn't

have been because of the water-power that Tillicoultry got established so

early as a place of manufacture, for no power of any kind was used in

those days. It must have been, as Mr. Watson suggests, because of the

abundant supply of wool close at hand. Wool was then carded with little

hand cards, and the yarn spun by women in their own homes, and neither the

carding-engine nor the spinning-mule had then been heard of.

The mode then in use for milling the blankets and

plaidings made from these home-spun yarns was by the women tramping them

with their feet, which must have been a very slow, tiresome, and

unsatisfactory process; and the very first object aimed at by our early

manufacturers was to get a more efficient method introduced for

accomplishing this object. This, therefore, more than for carding and

spinning, was the purpose for which the first mills here were principally

erected, and to which the water-power was first applied. Waulk mills were

erected, which would not only do the work much more efficiently and

quicker than before, but would also relieve the guidwives of what must

have been a very laborious and fatiguing operation (although tradition

says they were rather jealous of the innovation).

FIRST MILLS ERECTED IN TILLICOULTRY.

As far as can be learned, the first waulk mill erected

on Tillicoultry Burn was put up in the open air, by one Thomas Harrower,

in the end of last century; but where this mill stood no one seems now to

know. About this time, also, the first spinning mill in Tillicoultry was

built, by three brothers, named John, Duncan, and William Christie, which

is still standing, although used now only as a place of storage, and the

attic as a hand-loom weaving shop. It is situated above the upper bridge,

and is known as the Old Mill of Castle Mills.

The Messrs. Christie being very pushing men, particularly the brother

John, they soon found the one little mill too small for their operations;

and they then built what is known as the Old Mill of Robert Archibald &

Sons' works, at the 'middle of the town,' which was the second mill built

in the village. In both places waulk mills were erected, and a great trade

carried on in miffing goods to the country people round about.

The first carding-engine in Tillicoultry was erected in

'Betty Burns' house' (a little two-storied building opposite the

boiler-house door of Mr. Walker's mill), and must have been of a very

primitive kind; but whether it belonged to the Messrs. Christie or some

other one, there seems to be some doubt. It was driven by the hand, and

must have been quite as laborious an operation as the tread-mill, but of

course a decided step in advance of the little old hand cards. As to the

correctness, however, of this being the mode of driving the 'first carder

ever started here, there can be no doubt, as the old man who had been

employed at it told my informant (Mr. David Paton) that this was the way

it was driven.

The water-wheel for Messrs.

Christie's first mill was close to the east wall of the building, on the

outside, and was removed only about a dozen of years ago, power not being

then required for this part of the works.

About the same time that this primitive mode of driving a carding-engine

was in operation in Tillicoultry, there was one started in Alva, driven by

a horse, and Mr. Edward Moir recollects well of seeing it in operation. A

company of eight or nine gentlemen were connected with it, and they

afterwards built the next mill above Castle Mills in Tillicoultry, and it

often went by the name of the Horse Mill (in consequence of the company's

peculiar start in Alva), although no horse was ever used in it It was more

generally called the Company Mill, by which name it is still known. Six

members of this company were named—James Balfour, James Ritchie, James

Morrison, David Drysdale, William Rennie, John Cairns, and the name of the

firm was James Balfour & Co. A waulk mill was at once erected by them

here, and each member of the company got his turn at milling; and a worthy

old lady of our village remembers well of the goods being regularly

carried along from Alva, on their backs, to get milled here; and so great

were the demands on this mill, and so much difficulty experienced in

getting their goods milled in time, that it was often like to lead to

misunderstandings and unpleasantness amongst the various members of the

company. Mr. John Christie built and lived in

Burnside House, Tillicoultry, the residence at present of Mr. Scott and

family, and for such a long period of years previously of Mr. Robert

Archibald and family. He was the most active of the three brothers; and

when he died, the other two gave up the business, and emigrated to

America. As far as I have been able to learn, this would be about the year

1814 or 1815, as the old 'middle of the town mill' stood silent for two or

three years previous to Mr. Robert Archibald acquiring it.

INVENTION OF THE SPINNING-MULE.

About the year 1764 a very great discovery was made

(from a very trifling circumstance) in the art of spinning, which

completely revolutionized this branch of industry, and led to results the

importance and magnitude of which it is impossible to estimate. A

spinning-wheel having been accidentally overturned, the spindle (although

in a vertical position) continued to revolve, and the yarn to spin, as

before,—the thread slipping over the point of the spindle at every

revolution; and the idea at once suggested itself to James Hargreaves,

that if one spindle could do so, why not a number? and here was 'the germ'

of the spinning- mule. A small machine was at once constructed, with eight

spindles only, and got christened by the name of the Spinning Jenny. In

1770 Arkwright invented a spinning frame, which was a great improvement

upon the first attempt of Hargreaves; but the real author of the

spinning-mule was Samuel Crompton, who, by combining the invention of

Hargreaves with that of Arkwright, gave us that invaluable machine which

has continued in use ever since. This combination, or mongrel sort of

machine, had suggested the name of 'mule' for it, and hence it was so

named. The vastness of the results gained by its adoption may be judged of

from the fact that, in place of one spindle (as in the old

spinning-wheel), revolving at a very slow speed, a pair of mules have

frequently 1000 spindles, revolving about 4000 times a minute! Samuel

Crompton was born at Bolton in 1753, and died in 1827.

Several attempts were made, first by William Kelly, of

Lanark Mills, Scotland, Mr. Smith of Deanston, and others, to make the

spinning-mule self-acting; but the real inventor of the self-acting mule

was Richard Roberts, born in North Wales in 1789. It was not till

1830—when he also invented the quadrant motion —that the success of the

self-actor may be dated.

The head stock of the

self-actor is a most ingenious piece of mechanism, and shows Mr. Roberts

to have been a man of rare genius. Had a worthy man who lived in Dollar

when the wool mill was first started there, and who, on first seeing

through it, was much impressed with the ingeniousness of some of the then

primitive machinery, lived to see the self-acting mule, he would have had

more reason for the exclamation of surprise he gave utterance to, and

which so much amused his hearers: 'The works of nature are very wonderful,

but the works of man are more wonderful still.' Mr. Smith of Deanston was

the first to introduce the self-actors into Scotland, and to adapt them

for wool spinning; and the first self-acting mules for this purpose in the

United Kingdom were fitted up by him for Mr. William Drysdale, Braehead,

Alva, and Messrs. Robert Archibald & Sons, Tillicoultry. Great

improvements, however, have been made on them since then, and they are now

as near perfection as it is possible almost for them to be.

A very primitive sort of spinning machine, called a

Jack, was what was generally in use in Tillicoultry in the beginning of

this century; and it, like the carding engine, was driven by the hand.

Afterwards the spinning frame was introduced, driven at first also by the

band. An uncle of Mr. Edward Moir's (a Mr. David Lawson), wrought one of

those hand-spinning frames in the attic of Christie's first mill.

The hand-billey and hand - mules were the next

improvements introduced, and they were driven partly by hand and partly by

power. When the self-acting head stock was perfected, it was applied to

both the billey and the .mules, and self-acting machines of both kinds

were gradually introduced; and now, unless in small country mills,

hand-mules or billeys are rarely to be seen.

Some very extensive machine works are now in existence for the production

of carding and spinning machinery, one work alone, in England, giving

employment to between 5000 and 6000 hands.

INVENTION OF THE PIECING MACHINE AND CONDENSER.

When carding wool by the carding-engine was first

introduced (and for long afterwards), the rovings, or rolls of wool that

were taken off the carder (from sheets of card set apart from each other)

for the foundation of the thread, were rubbed together or 'pieced' at the

billey by the hand; which must have caused very irregular yarn, and no

little pain to the children's hands, which were often bleeding at night.

By and by, however, a piecing machine was invented by Mr. John Archibald

of Keilersbrae ('Uncle John,' so called to distinguish him from his nephew

of the same name), for joining these rovings together, which did the work

much more efficiently, and dispensed with the services of some three or

four children for each billey. This piecing machine was afterwards greatly

improved, first by James Melrose & Sons, Hawick, and was afterwards

further improved by Mr. Archibald of Devondale; and where bileys are still

used, Mr. Archibald's is the one now in general favour.

The mechanical genius of our age being ever 'at work,

an invention was afterwards brought out that dispensed entirely with

piecing machines and billeys, and which not only saves time and labour,

but makes a much better yarn,—that was the condenser. In place of the wool

coming off the carder in thick rolls, from sheets of card placed across

the machine, it comes off the condenser dotter (from narrow rings of card

put round it) in small, continuous slivers, and thus no piecing is

required; and these are rubbed or 'condensed' into small soft threads,

which are then taken to the mules and spun into yarn. This mode of making

yarn is now almost universally adopted, although piecing machines and

billeys are still in use in small country mills, and even hand-piecing, I

learned the other day, is not yet quite extinct. As the billey is a large

machine, and takes up a great deal of room, a great saving of space has

been effected by its discontinuance.

DETAILED NOTICE OF THE PUBLIC WORKS

IN TILLICOULTRY.

About the beginning of the

present century, three brothers, named John, William, and Robert

Archibald, left Tullibody and started a small woollen mill in Menstrie.

They were destined afterwards to play an important part in the opening up

of the woollen trade at the foot of the Ochils, and some of their

descendants are at the present day proprietors of some of our largest

manufacturing establishments. Either direct or by marriage, the

descendants of those three brothers are, or have been, connected with nine

of our public works, viz. the original mill at Menstrie; Strude Mill,

Alva; (2raigfoot Mill; Robert Archibald & Sons; J. & D. Paton's, and J. &

R. Archibald's works, Devondale, Tillicoultry; Keillersbrae, Gaberston,

and Kilncraigs Works, Aba. Mr. William Archibald, of Strude Mill, Alva,

and Mr. John Archibald, of Keilersbrae ('Uncle John'), were sons of Mr.

John Archibald, of Menstrie. Messrs. John, William, and Andrew Archibald,

of Keillersbrae new mill, were grandsons; Mrs. Lambert, of Gaberston, was

a grand-daughter; and Mrs. John Thomson Paton, of Norwood, a

great-grand-daughter. The first Mrs. James Paton and first Mrs. David

Paton were daughters of Mr. William Archibald, of Craigfoot, Tillicoultry,

one of the three brothers who left Tullibody for Menstrie.

In 1806 Mr. William Archibald left Menstrie for

Tillicoultry, and built the third mill of the village at Craigfoot (which

at present forms the back wing of the works), and pushed the trade very

successfully for a great many years.

Mr.

Robert followed him in 1817 (two or three years after the Messrs. Christie

left Tillicoultry), and bought the second mill they built at 'the middle

of the town,' and started the firm of Robert Archibald & Sons.

Mr. John continued in Menstrie, and carried on the

original mill there, which was after his death carried on for such a very

long period by his two sons, Mr. Andrew and Mr. Peter.

The village of Tullibody (we learn from the Statistical

Account) claims a comparatively high antiquity. About the year 834,

Kenneth king of the Scots assembled his army on the rising ground close to

where this village now stands, previous to attacking the army of the Picts,

under Druskein, their monarch, who had put Kenneth's father to death, and

on whom he was determined to be revenged. Having completely defeated the

Pictish army, he pursued them to the river Forth, near Stirling, and thus

fully accomplished the object he had in view. Returning to where his army

had encamped before the battle, he caused a stone to be erected where the

royal standard had stood, as a memorial of the victory; and this stone was

only removed about fifty years ago. The spot, however, where it stood is

well known to the neighbourhood, and still receives the name of the '

stan'in' stane.' 'A little to the east of the field where the main body of

his army was encamped, he also founded a village, which he called "Tirlybothy"

(since varied into Tullibodie and Tullibody), a name originally signifying

"the oath of the croft." Such was the origin of this village. For upwards

of three centuries subsequent to the period mentioned, little of its

history is known.' Tullibody Church is a small but venerable edifice,

having been built by David I., king of Scotland, in the year 1149, nearly

700 years ago. Two years previous to this, he had also built the splendid

Abbey of Cambuskenneth, on the very spot where his royal ancestor Kenneth

gave the fatal blow to the Pictish dominion. 'The churches, with their

tithes and pertinents, belonging to this abbey, were those of Clackmannan

with its chapels, Tillicoultry, Kincardine, St. Ninians with its chapels,

Alva, Tullibody, with its chapels at Alloa, etc. The first Abbot was

called Aifredius.'

For upwards of 400 years

the rites of the Roman Catholic faith were celebrated in Tullibody Church.

It is recorded that in the year 1559 it was unroofed by the French, who

under Monsieur d'Oysel were retreating on Stirling, on hearing that the

English fleet had arrived on the coast of Fife. Kirkcaldy of Grange, in

order to arrest their progress, broke down the bridge of Tullibody over

the Devon, about a mile to the west of the village, and the French

unroofed the church, and used the materials for a temporary bridge. The

church continued in this dismantled state for about 200 years, when it was

roofed in by George Abercromby, Esq., of Tullibody, and used by the family

as a place of sepulture. About fifty years ago it was fitted up by

subscription as a preaching station.

In order

to get water to such a high situation as Craigfoot (fixed on by Mr.

William Archibald for his mill), two formidable undertakings had to be

accomplished,—the formation of a dam far up the glen, and the construction

of a lade to convey the water from it to the mill. From the great length

of the latter, and the immense depth of it at one part below the surface

(20 feet at least), they must have cost him, or the laird, a very large

sum of money. Besides other machinery, Mr.

Archibald put in a waulk mill at Craigfoot, which soon brought him into

trouble with the inhabitants of the village. There being no common sewer

in those days, as at present, the waulk mill water was run into the burn

above the village; and the inhabitants naturally rebelled against this,

and insisted on its being stopped. Not being able to come to a

satisfactory arrangement about it, the guidwives of the village, armed

with axes, hammers, etc., proceeded in a body to the dam-head, and soon

completely demolished it, which of course would put a stop to all

operations at the mill, and throw all the workers idle. It was, however,

got quietly constructed a second time during the night, soon after; and no

sooner was this known than the irate ladies proceeded to the work of

destruction again, and soon made short work of the erection. (Mr. Moir,

who informed me of these incidents, remembers well of the excitement

caused in the village at the time, and of seeing the wives proceeding with

their implements to the work of destruction.) Things having now reached a

crisis, something required to be done to put a stop to such a state of

matters, and Mr. Johnstone of Alva (the present. Mr. Johnstone's father)

allowed Mr. Archibald to make a sewer for the dirty water down through his

plantation into the sunk fence of his fields; and thus an end was put to

the strife. About the same time that Mr.

Robert Archibald got the middle of the town mill, the other mill built by

the Messrs. Christie at Castle Mills was bought by a Mr. Robert Walker,

who came about that time, with a grown-up family, from Galashiels.

In 1820 his two eldest sons, James and George, built

the mill immediately below the upper bridge, and started business there

under the firm of J. & G. Walker. This business was very successfully

carried on for a great many years, and when Mr. George Walker (the present

Mr. Robert Walker's father) died, he was possessed of very considerable

wealth. Shortly after this mill was built, a

younger brother, named Andrew, built the New Mill of Castle Mills; and

when I came to Tillicoultry, it went always by the name of 'Andrew

Walker's Mill.' He erected a large gaswork within the grounds, which

supplied (in addition to his own works) the whole of the village with gas.

A very singular coincidence in connection with this family was, that those

three brothers, and also another brother, all died at the age of

forty-two. James died in 1832, George in 1841, and Andrew in 1843.

The next mill to Craigfoot was built by a Mr. James

Dawson, about the year 1811 or 1812. Although now the property of Mr.

Cairns, it still goes by the name of Dawson's Mill. The one below it was

built about the same time by the company of gentlemen from Alva (James

Balfour & Co.) already referred to, and is still known by its old name of

'The Company Mill;' but at one time, as already stated, it was

occasionally called 'The Horse Mill.'

After

Mr. William Archibald's death in 1826) his business was carried on for

thirteen years by Mrs. Archibald; and hence Craigfoot was very generally

called, when I came to Tillicoultry, 'The Widow's Mill.' One of Mr.

Archibald's first carding-engines still stands in the Old Mill

(unused);--a relic of bygone days.

In 1838 the

large new mill (with its giant water wheel-35 feet diameter) was built;

and in 1839 Mr. Archibald's two sons, Mr. John and Mr. Robert, took over

the business, and started the new firm of J. & R. Archibald, which has

been carried on so successfully now for forty-three years. The business

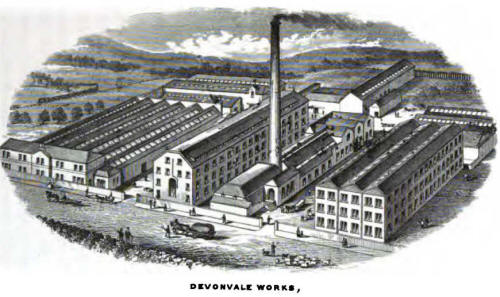

extended so rapidly, that in 1846 the first part of the extensive works at

Devonvale was built, which has since been added to so very largely. Mr.

John died on the list of January 1848, at the early age of thirty-five;

and the business has, since then, been carried on solely by Mr. Robert,

until his Sons were old enough to assist him in it. Craigfoot and

Devonvale were both carried on by the firm till 1851, when the business

was transferred entirely to Devonvale. The class of goods manufactured by

this firm is of the very best description, and has long taken a first

place in the tweed trade,—the name of 'Devoiivale' (as with the Aba yarn)

being a sufficient guarantee for the superiority of the goods. As a

specimen of some of our modern manufacturing premises, I herewith give a

view of their extensive and beautiful works. The mill to the south (the

last one built) is generally considered 'a model' of what a spinning mill

ought to be. Those works are situated very near the railway station. Mr.

William Archibald's old rent-book for the water-power and feu-duty of

Craigfoot Mill, which commenced in 1807, is in my possession now, and is

still used by me when paying these to James Johnstone, Esq. of Alva. This

little passbook is very interesting, from the fact that it is now

seventy-five years old, and is quite a little history in itself regarding

the factors on the Alva estate. A Mr. Alexander Littlejohn received the

first feu-duty for Craigfoot Mill in 1807, and he continued factor till

1816. Mr. John M'Laren, of Burnside of Alva, followed him, and continued

for the long period of thirty-one years. Mr. James Kerr, writer in

Stirling, succeeded Mr. M'Laren, and acted for nine years; and then Mr.

James Moir, banker, Alloa, followed, and continued for fifteen years, from

1859 till 1874; and after his death Mr. Archibald Moir, his brother, was

appointed, and is now factor at the present time.

The most extensive and prosperous business in our

village was commenced in 1824, by Messrs. James and David Paton (the two

eldest sons of the late Mr. John Paton of Kilncraigs, Alloa), under the

firm of J. & D. Paton. From a very small beginning, this business

gradually extended, and has been for many years the principal mainstay of

the working population of Tillicoultry, a very large number of hands being

employed by the firm. Their goods have long been celebrated throughout the

country; and at the first Great Exhibition in London in 1851, they

obtained the gold medal for their exhibits. The works now cover a very

large piece of ground, and contain seventeen sets of carding and spinning

machinery, and upwards of 250 power and hand looms. Both gentlemen have

given very largely of their wealth for the cause of Christ, both at home

and abroad; and Mr. James built a very handsome manse for the U.P. Church

here, bought the old manse, and presented it to the village for a British

Workman Public House.

Mr. James's two sons—Mr.

John and Mr. James— were taken into the firm a great many years ago, and

up till 1875 both together took the active management of the business. In

that year, however, on the 3rd of March, Mr. James was taken away at the

early age of forty-three; and his death was a great blow to all the

friends, and must have been particularly so to his brother, with whom he

had all along been associated. Since that year the management has devolved

principally upon Mr. John; and the loss of the counsel and assistance of

such a shrewd, active business young man as Mr. James was, must have been

very much felt by him. Mr. James left £5000 to found an orphanage in his

native village; and this has proved a very great blessing indeed. A

beautiful house was erected in Ochil Road, and, under the motherly care of

Mrs. Currie, who was appointed to take charge of it, from eight to ten

orphans have been enjoying all the comforts of a nice home, and having not

only their temporal but their eternal interests well looked after.

From the present state of the health of Mr. James Paton,

senior, and the long-existing copartnery being about to expire, it is more

than probable that Mr. John will after this be the sole proprietor of

these extensive works and prosperous business.

The firm of Robert Archibald & Sons consisted of the

father and four sons,—Messrs. William, Robert, Duncan, and James. The

original mill, bought by the firm in 1817, proving too small for their

increasing business, their new mill was built in 1836, adjoining which

there have since been added a very large power- loom shed and other

extensive premises, and further extensions are in contemplation. For many

years they have been doing a large and profitable business, and have

become quite celebrated throughout the trade as the makers of the finest

woollen shirtings that are produced; and they are, in consequence, kept

always busy, and give employment to a very large number of hands. They

have now close on one hundred power- looms, besides a large number of

hand-looms, and manufacture tweeds as well as 8hirtings. Mr. Archibald,

senior, died in 1849. Mr. William retired from the business in 1858. Mr.

Robert died in 1868, and Mr. Duncan in 1874. The only member of the

original firm then left being Mr. James, he assumed as partners, in 1875,

Mr. Robert, his son, and Mr. Alexander Scott. Mr. Archibald has laid our

village under a deep debt of gratitude to him, by building a very handsome

tower to our Town Hall, and providing it with a clock and bell, at a cost

of about £1500. He has been, for upwards of a dozen years, the

much-respected captain of our rifle volunteer corps, and is proprietor of

the beautiful villa of Beechwood.

When

referring to our Town Hall, or 'Popular Institute, as it is generally

called, I think it right to state, in passing, that the inhabitants of

Tillicoultry are indebted to the late Mr. Archibald Browning, junior, for

initiating the movement which culminated in the erection of this fine

building. It was he who gave it the name it still bears; and both he and

his brother, the late Mr. Richard Browning, exerted themselves most

energetically in getting funds raised for carrying the project through. It

has been a great acquisition to our town, and I think it ought not to be

forgotten who the originator of it was, and to whose exertions the village

is so largely indebted for the carrying out of the scheme to a successful

termination. Mr. Archibald Browning, junior, died on August 2nd, 1854. Mr.

Richard died on the 25th July 1855; and Miss Catherine Browning in March

1855.

FIRST POST-OFFICE IN

TILLICOULTRY. Mr. Thomas Walker was appointed

the first postmaster in Tillicoultry in 1833, and his widow is still our

much-respected post-mistress; so that Mrs. Walker has now been connected

with our post-office for the long period of fifty years. Mr. Walker died

in 1852. I am sure I only express the feeling of the whole community when

I say, that during all those years our post-office has been conducted to

the entire satisfaction of every one.

During

the long period that Mrs. Walker has been at the head of our post-office

here, she has seen many improvements introduced in connection with

it,—such as the penny postage, the savings bank, money orders, the

telegraph, etc., and she informs the writer that they frequently send and

receive more telegrams in a day now, than they used to do of letters in

the days of the dear postage. The active duties of the office are now

being conducted by her son, Mr. William, her daughter, Miss Walker, and

her grand-daughter, Miss Anderson.

The

telegraph from Alloa to Tillicoultry was constructed in the year 1860, and

cost above £100, one half of which was paid by the railway company, and

the other half by the inhabitants of Tillicoultry. And so little faith had

the telegraph company in its being self-supporting, that a few individuals

had to guarantee the clerk's salary for the first year, before they would

agree to erect it. The guarantors, however, were never called upon to make

up any deficiency, as it was largely taken advantage of from the very

first, and proved quite a paying concern.

In

the year 1839, a Mr. John Henderson built the only woollen mill at that

time not in connection with the burn, the water for the steam-engine of

which was got from the Ladies' Well. This mill was three stories in

height, and was occupied by three different parties, viz. Mr. Henderson,

Mr. Thomson Dawson, and Mr. Alexander Robertson. It was destined, however,

to have a very short career; for, one evening about seven o'clock, in the

spring of 1842, the cry of 'Fire!' was suddenly heard, and in little more

than an hour the whole pile was reduced to ashes, and nothing left but the

blackened walls. I don't know how the others' stood for insurance, but Mr.

Robertson was not insured at all, and this disastrous fire completely

ruined him. From being a manufacturer on a considerable scale, he was at

once reduced to a weaver, and was working on the loom when I came to

Tillicoultry. This Alexander Robertson (or 'Sandy Robertson,' as he was

generally called) was, by the way, one of our very best curlers,— although

left-handed,—and considered one of the best skips in the club. The walls

of this mill stood for thirty-five years in a ruinous state, and it was

always known as 'The Burnt Mill.' In 1874, however, it was turned again

into a substantial building, by having its walls thoroughly repaired and

roofed in ; and now a large portion of it is turned into a dye-house, and

carried on by Mr. George Brownlee—on a very extensive scale—as the

Lady-Well Dyeworks, where 'plant' of the very newest description has been

introduced, including a large blue vat; while the other portion of it has

been turned into a weaving shop, and carried on by Messrs. Robert

Archibald & Sons. In place, then, of this part of the village having a

desolate and forlorn look, as it had for such a long period, all is now

bustle and activity.

It may not be out of

place here, when taking notice of 'The Burnt Mill,' to give our own

experience of tires (those ever-to-be-dreaded calamities of the

mill-owner), of which we have, unfortunately, had more than the average

share. In the month of March 1858, when busy

in the office one day, we were suddenly startled by seeing a black cloud

of smoke rushing past the office window, and, on running out to see what

was the cause of it, were horrified to find the big mill on fire, and the

under fiat filled with smoke as black as coal. We at once gave the mill up

for lost, and were, of course, in a great state of excitement and alarm.

However, not a moment had to be lost, and a double row of hands was at

once arranged from the mill door to the lade, and a constant supply of

water poured on the floor above where the fire was, which was effectual in

drowning it out before the fire-engines (which had been sent for) arrived.

This was not accomplished, however, till upwards of £300 of damage had

been done. Nothing, however, could have saved the mill but for an

extraordinary feat that was performed by our old ex-foreman, John Gentles.

The day having been a very dull one, the gas was partially lighted through

the mill, and the sagacious old man saw at a glance that unless the big

meter could be turned off, the mill was sure to be lost. But here was the

difficulty. The entrance door of the flat where the fire was was, at the

one end of the mill, and the meter stood at the other end, and to reach it

the whole length of the mill had to be traversed through black,

suffocating smoke, in which I couldn't have lived for a second or two; and

into this pit this devoted man plunged, walked the whole length of the

mill, turned off the meter, walked all the way back again, and came out

alive. How this feat was accomplished astonished every one, as it really

seemed little short of a miracle.

After the

fire was extinguished, we found that this noble act of his had saved the

mill. The main gas-pipe had been blazing, and was meted fully halfway

along the mill, and in another minute or two it would have reached the

perpendicular 'main' for the flats above; and then all would have been

lost.

This fire originated at the teazer, while teazing a

batch of Angola wool, which is a very inflammable material when once it is

started; and but for the abundant supply of water immediately at hand, all

efforts to put it out would have proved abortive.

After this fire, the teazer was at once removed to a

separate house, and a stopcock placed on the gas supply pipe, outside the

mill. Our next experience of this dreaded foe

was in the month of July 1863. On arriving at the railway station from the

east one day, a messenger was waiting for me with the unwelcome news that

the teazer-house, with all its contents, was burned down. This of course

was very vexatious, as it seriously interfered with our operations, and,

until new teazers could be got ready, would put us very much about

However, with the kind help of our neighbours, we had just to do the best

we could, and use every precaution possible against a like calamity

occurring again.

Our next and last experience

of fire (and I earnestly hope it may be the last) was a much more serious

affair than the teazer-house, and, happening as it did through the night,

gave us all a dreadful shock. About three o'clock on a dark, foggy morning

in November 1876, I was awakened out of a sound sleep by hearing 'Fire!

fire! fire!' shouted most lustily in front of our house; and on opening

the window and asking where it was, was answered, At the head Ptoon' (a

very common designation for our works). On looking in the direction of the

mill, I was alarmed to see the whole heavens lighted up with a very big

fire, and concluded at once it was all over with the big mill. I found,

however, on getting to the street—and to my great relief—that it was only

the dry-house. This building, however (125 feet long, and two stories and

attics high), was ablaze from end to end, and a very formidable-looking

fire it was. The fire-engines were at work when I got there, but all they

could do was to prevent the fire spreading to the other buildings, and in

this they were successful; but the dry-house, with all its contents, was

burned to the ground. In rebuilding this house, we made it 'fire-proof' by

putting in an iron floor above the flue. An old saying is, 'Burnt bairns

dread the fire,' and our repeated experiences of this 'useful servant but

bad master' has made us use every possible precaution against the

recurrence of a like calamity. An extineteur and six pails of water are

kept always ready in every flat of the mill, and all material that is apt

to take fire spontaneously removed from the mill daily.

The millwright and machine works of Messrs. James

Wardlaw & Sons have been in existence since 1824, and were established at

first by a Mr. Robert Hall, Mr. William Ross, and Mr. James Wardlaw (Sir

Henry Wardlaw, Baronet's, father), under the firm of Robert Hall & Co.,

and have all along been the only public works of the kind in the village.

Their first premises were situated nearly opposite the Crown Hotel, and

were the first buildings on the south side of the High Street. Their

present works were erected in 1839, and after the death of Mr. Ross and

Mr. Hall (the former about forty years ago, and the latter some fifteen

years afterwards), the firm was changed to James Wardlaw & Sons. Sir Henry

Wardlaw, Bart., is now the sole partner of this old-established firm. He

succeeded to the baronetcy in 1877, on the death of his father's cousin,

Sir Archibald Wardlaw, Bart., who lived in Edinburgh. The Wardlaw

baronetcy dates from 1631; and for a very full and interesting account of

it from that time till the present day, see the Tillicoultry News of

January the 18th, 1882, or Dod's Peerage, Baronetage, and Knighthood of

Great Britain and Ireland for 1882. Mr. James Wardllaw (Sir Henry's

father) died in 1867.

In this record of the

early public works of Tillicoultry, I must not omit to mention a fine mill

that was erected by a Mr. Robert Marshall, about the year 1836. Not having

been successful in business, this mill came into the market for sale, and

was bought by the Messrs. Paton, and is now incorporated with their works.

It is the end building of the south wing, and on the right-band side as

you enter their works. |