Bell

heard this verdict from behind the door, and gave way utterly, but

Drumsheugh declined to accept it as final, and devoted himself to

consolation.

Bell

heard this verdict from behind the door, and gave way utterly, but

Drumsheugh declined to accept it as final, and devoted himself to

consolation.

"Dinna greet like that,

Bell wumman, sae lang as Saunders is still livin’; a’ll never give up houp,

for ma pairt, till oor ain man says the word.

"A’ the doctors in the land

dinna ken as muckle aboot us as Weelum MacLure, an’ he’s ill tae beat when

he’s trying tae save a man’s life."

MacLure, on his coming,

would say nothing, either weal or woe, till he had examined Saunders.

Suddenly his face turned into iron before their eyes, and he looked like

one encountering a merciless foe. For there was a feud between MacLure and

a certain mighty power which had lasted for forty years in Drumtochty.

"The London doctor said

that Saunders wud sough awa afore mornin’, did he? Weel, he’s an authority

on fevers an’ sic like diseases, an’ ought tae ken.

"It’s

may be presumptous o’ me tae differ frae him, and it wudna be verra

respectfu’ o’ Saunders tae live aifter this opeenion. But Saunders wes awe

thraun an’ ill tae drive, an’ he’s as like as no tae gang his own gait.

"It’s

may be presumptous o’ me tae differ frae him, and it wudna be verra

respectfu’ o’ Saunders tae live aifter this opeenion. But Saunders wes awe

thraun an’ ill tae drive, an’ he’s as like as no tae gang his own gait.

"A’m no meanin’ tae reflect

on sae clever a man, but he didna ken the seetuation. He can read fevers

like a buik, but he never cam across sic a thing as the Drumtochty

constitution a’ his days.

"Ye see, when onybody gets

as low as puir Saunders here, it’s juist a hand to hand wrastle atween the

fever and his constitution, an’ of course, if he had been a shilpit,

stuntit, feckless effeegy o’ a cratur, fed on tea an’ made dishes and

pushioned wi’ bad air, Saunders wud hae nae chance; he wes boond tae gae

oot like the snuff o’ a candle.

"But Saunders hes been

fillin’ his lungs for five and thirty year wi’ strong Drumtochty air, an’

eatin’ naethin’ but kirny aitmeal, and drinkin’ naethin’ but fresh milk

frae the coo, an’ followin’ the ploo through the new-turned sweet-smellin’

earth, an’ swingin’ the scythe in haytime and harvest, till the legs an’

airms o’ him were iron, an’ his chest wes like the cuttin’ o’ an oak tree.

"He’s a waesome sicht the

nicht, but Saunders wes a buirdly man aince, and wull never lat his life

be taken lichtly frae him. Na, na, he hesna sinned against Nature, and

Nature ‘ill stand by him noo in his oor o’ distress.

"A’ daurna say yea, Bell,

muckle as a’ wud like, for this is an evil disease, cunnin, an’

treacherous as the deevil himsel’, but a’ winna say nay, sae keep yir hert

frae despair.

"It wull be a sair fecht,

but it ‘ill be settled one wy or anither by sax o’clock the morn’s morn.

Nae man can prophecee hoo it ‘ill end, but ae thing is certain, a’ll no

see deith tak a Drumtochty man afore his time if a’ can help it.

"Noo, Bell ma wumman, yir

near deid wi’ tire, an’ nae wonder. Ye’ve dune a’ ye cud for yir man, an’

ye’ll lippen (trust) him the nicht tae Drumsheugh an’ me; we ‘ill no fail

him or you.

"Lie doon an’ rest, an’ if

it be the wull o’ the Almichty a’ll wauken ye in the mornin’ tae see a

livin’ conscious man, an’ if it be itherwise a’ll come for ye the suner,

Bell," and the big red hand went out to the anxious wife. "A’ gie ye ma

word."

Bell

leant over the bed, and at the sight of Saunders’ face a superstitious

dread seized her.

Bell

leant over the bed, and at the sight of Saunders’ face a superstitious

dread seized her.

"See, doctor, the shadow of

deith is on him that never lifts. A’ve seen it afore, on ma father an’

mither. A’ canna leave him, a’ canna leave him."

"It’s hoverin’, Bell, but

it hesna fallen; please God it never wull. Gang but and get some sleep,

for it’s time we were at oor work.

"The doctors in the toons

hae nurses an’ a’ kinds o’ handy apparatus," said MacLure to Drumsheugh

when Bell had gone, "but you an’ me ‘ill need tae be nurse the nicht, an’

use sic things as we hev.

"It ‘ill be a lang nicht

and anxious wark, but a’ wud raither hae ye, auld freend, wi’ me than ony

man in the Glen. Ye’re no feared tae gie a hand?"

"Me feared? No, likely.

Man, Saunders cam tae me a haflin, and hes been on Drumsheugh for twenty

years, an’ though he be a dour chiel, he’s a faithfu’ servant as ever

lived. It’s waesome tae see him lyin’ there moanin’ like some dumb animal

frae mornin’ tae nicht, an’ no able tae answer his ain wife when she

speaks.

"Div ye think, Weelum, he

hes a chance?"

"That he hes, at ony rate,

and it ‘ill no be your blame or mine if he hesna mair."

While he was speaking,

MacLure took off his coat and waistcoat and hung them on the back of the

door. Then he rolled up the sleeves of his shirt and laid bare two arms

that were nothing but bone and muscle.

"It gar’d ma very blood rin

faster tae the end of ma fingers juist tae look at him," Drumsheugh

expatiated afterwards to Hillocks, "for a’ saw noo that there was tae be a

stand-up fecht atween him an’ deith for Saunders, and when a’ thocht o’

Bell an’ her bairns, a’ kent wha wud win.

"‘Aff wi’ yir coat,

Drumsheugh,’ said MacLure; ‘ye ‘ill need tae bend yir back the nicht;

gither a’ the pails in the hoose and fill them at the spring, an’ a’ll

come doon tae help ye wi’ the carryin’.’"

It was a wonderful

ascent up the steep pathway from the spring to the cottage on its little

knoll, the two men in single file, bareheaded, silent, solemn, each with a

pail of water in either hand, MacLure limping painfully in front,

Drumsheugh blowing behind; and when they laid down their burden in the

sick room, where the bits of furniture had been put to a side and a large

tub held the centre, Drumsheugh looked curiously at the doctor.

It was a wonderful

ascent up the steep pathway from the spring to the cottage on its little

knoll, the two men in single file, bareheaded, silent, solemn, each with a

pail of water in either hand, MacLure limping painfully in front,

Drumsheugh blowing behind; and when they laid down their burden in the

sick room, where the bits of furniture had been put to a side and a large

tub held the centre, Drumsheugh looked curiously at the doctor.

"No, a’m no daft; ye needna

be feared; but yir tae get yir first lesson in medicine the nicht, an’ if

we win the battle ye can set up for yersel in the Glen.

"There’s twa dangers --

that Saunders’ strength fails, an’ that the force o’ the fever grows; and

we have juist twa weapons.

"Yon milk on the drawers’

head an’ the bottle of whisky is tae keep up the strength, and this cool

caller water is tae keep doon the fever.

"We ‘ill cast oot the fever

by the virtue o’ the earth an’ the water."

"Div ye mean tae pit

Saunders in the tub?"

"Ye hiv it noo, Drumsheugh,

and that’s hoo a’ need yir help."

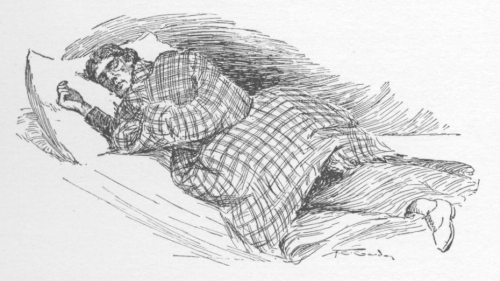

"Man, Hillocks," Drumsheugh

used to moralize, as often as he remembered that critical night, "it wes

humblin’ tae see hoo low sickness can bring a pooerfu’ man, an’ ocht tae

keep us frae pride.

"A month syne there wesna a

stronger man in the Glen than Saunders, an’ noo he wes juist a bundle o’

skin and bone, that naither saw nor heard, nor moved nor felt, that kent

naethin’ that was dune tae him.

"Hillocks, a’ wudna hae

wished ony man tae hev seen Saunders—for it wull never pass frae before ma

een as long as a’ live—but a’ wish a’ the Glen hed stude by MacLure

kneelin’ on the floor wi’ his sleeves up tae his oxters and waitin’ on

Saunders.

"Yon big man wes as pitifu’

an’ gentle as a wumman, and when he laid the puir fallow in his bed again,

he happit him ower as a mither dis her bairn."

Thrice it was done,

Drumsheugh ever bringing up colder water from the spring, and twice

MacLure was silent; but after the third time there was a gleam in his eye.

"We’re haudin’ oor ain;

we’re no bein’ maistered, at ony rate; mair a’ canna say for three oors.

"We ‘ill no, need the water

again, Drumsheugh; gae oot and tak a breath o’ air; a’m on gaird masel."

It was the hour before

daybreak, and Drumsheugh wandered through fields he had trodden since

childhood. The cattle lay sleeping in the pastures; their shadowy forms,

with a patch of whiteness here and there, having a weird suggestion of

death. He heard the burn running over the stones; fifty years ago he had

made a dam that lasted till winter. The hooting of an owl made him start;

one had frightened him as a boy so that he ran home to his mother—she died

thirty years ago. The smell of ripe corn filled the air; it would soon be

cut and garnered. He could see the dim outlines of his house, all dark and

cold; no one he loved was beneath the roof. The lighted window in

Saunders’ cottage told where a man hung between life and death, but love

was in that home. The futility of life arose before this lonely man, and

overcame his heart with an indescribable sadness. What a vanity was all

human labour, what a mystery all human life.

But while he stood, subtle

change came over the night, and the air trembled round him as if one had

whispered. Drumsheugh lifted his head and looked eastwards. A faint grey

stole over the distant horizon, and suddenly a cloud reddened before his

eyes. The sun was not in sight, but was rising, and sending forerunners

before his face. The cattle began to stir, a blackbird burst into song,

and before Drumsheugh crossed the threshold of Saunders’ house, the first

ray of the sun had broken on a peak of the Grampians.

MacLure left the bedside,

and as the light of the candle fell on the doctor’s face, Drumsheugh could

see that it was going well with Saunders.

"He’s nae waur; an’ it’s

half six noo; it’s ower sune tae say mair, but a’m houpin’ for the best.

Sit doon and take a sleep, for ye’re needin’ ‘t, Drumsheugh, an’, man, ye

hae worked for it."

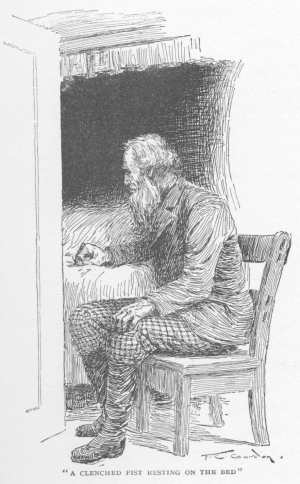

As

he dozed off, the last thing Drumsheugh saw was the doctor sitting erect

in his chair, a clenched fist resting on the bed, and his eyes already

bright with the vision of victory.

As

he dozed off, the last thing Drumsheugh saw was the doctor sitting erect

in his chair, a clenched fist resting on the bed, and his eyes already

bright with the vision of victory.

He awoke with a start to

find the room flooded with the morning sunshine, and every trace of last

night’s work removed.

The doctor was bending over

the bed, and speaking to Saunders.

"It’s me, Saunders; Doctor

MacLure, ye ken; dinna try tae speak or move; juist let this drap milk

slip ower—ye ‘ill be needin’ yir breakfast, lad—and gang tae sleep again."

Five minutes, and Saunders

had fallen into a deep, healthy sleep, all tossing and moaning come to an

end. Then MacLure stepped softly across the floor, picked up his coat and

waistcoat, and went out at the door.

Drumsheugh arose and

followed him without a word. They passed through the little garden,

sparkling with dew, and beside the byre, where Hawkie rattled her chain,

impatient for Bell’s coming, and by Saunders’ little strip of corn ready

for the scythe, till they reached an open field. There they came to a

halt, and Doctor MacLure for once allowed himself to go.

His coat he flung east and

his waistcoat west, as far as he could hurl them, and it was plain he

would have shouted had he been a complete mile from Saunders’ room. Any

less distance was useless for the adequate expression. He struck

Drumsheugh a mighty blow that wellnigh levelled that substantial man in

the dust and then the doctor of Drumtochty issued his bulletin.

"Saunders wesna tae live

through the nicht, but he’s livin’ this meenut, an’ like to live.

"He’s got by the warst

clean and fair, and wi’ him that’s as good as cure.

"It’ ill be a graund

waukenin’ for Bell; she ‘ill no be a weedow yet, nor the bairnies

fatherless.

"There’s nae use glowerin’

at me, Drumsheugh, for a body’s daft at a time, an’ a’ canna contain masel’

and a’m no gaein’ tae try."

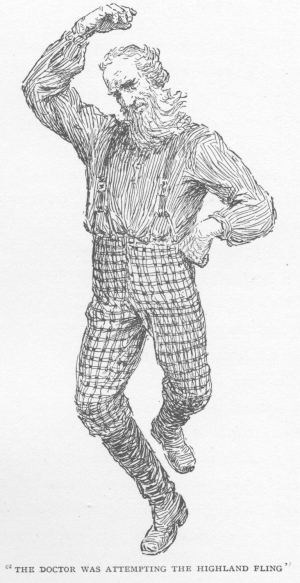

Then

it dawned on Dramsheugh that the doctor was attempting the Highland fling.

Then

it dawned on Dramsheugh that the doctor was attempting the Highland fling.

"He’s ‘ill made tae begin

wi’," Drumsheugh explained in the kirkyard next Sabbath, "and ye ken he’s

been terrible mishannelled by accidents, sae ye may think what like it wes,

but, as sure as deith, o’ a’ the Hielan flings a’ ever saw yon wes the

bonniest.

"A’ hevna shaken ma ain

legs for thirty years, but a’ confess tae a turn masel. Ye may lauch an’

ye like, neeburs, but the thocht o’ Bell an’ the news that wes waitin’ her

got the better o’ me."

Drumtochty did not laugh.

Drumtochty looked as if it could have done quite otherwise for joy.

"A’ wud hae made a third

gin a hed been there," announced Hillocks, aggressively.

"Come on, Drumsleugh," said

Jamie Soutar, "gie’s the end o’t; it wes a michty mornin’."

"’We’re twa auld fules,’

says MacLure tae me, and he gaithers up his claithes. ‘It wud set us

better tae be tellin’ Bell.’

"She was sleepin’ on the

top o’ her bed wrapped in a plaid, fair worn oot wi’ three weeks’ nursin’

o’ Saunders, but at the first touch she was oot upon the floor.

Is Saunders deein’,

doctor?’ she cries. ‘Ye promised tae wauken me; dinna tell me it’s a’ ower.’

"‘There’s nae deein’ aboot

him, Bell; ye’re no tae lose yir man this time, sae far as a’ can see.

Come ben an’ jidge for yersel’.’

"Bell lookit at Saunders,

and the tears of joy fell on the bed like rain.

"The shadow’s lifted,’ she

said; ‘he’s come back frae the mooth o’ the tomb.

"‘A’ prayed last nicht that

the Lord wud leave Saunders till the laddies cud dae for themselves, an’

thae words came intae ma mind, "Weepin’ may endure for a nicht, but joy

cometh in the mornin’."

"‘The Lord heard ma prayer,

and joy hes come in the mornin’,’ an’ she gripped the doctor’s hand.

"‘Ye’ve been the

instrument, Doctor MacLure. Ye wudna gie him up, and ye did what nae ither

cud for him, an’ a’ve ma man the day, and the bairns hae their father.’

"An’ afore MacLure kent

what she was daein’, Bell lifted his hand to her lips an’ kissed it."

"Did she, though?" cried

Jamie. "Wha wud hae thocht there wes as muckle spunk in Bell?"

"MacLure, of coorse, was

clean scandalized," continued Drumsheugh, "an’ pooed awa his hand as if it

hed been burned.

"Nae man can thole that

kind o’ fraikin’, and a’ never heard o’ sic a thing in the parish, but we

maun excuse Bell, neeburs; it wes an occasion by ordinar," and Drumsheugh

made Bell’s apology to Drumtochty for such an excess of feeling.

"A’ see naethin’ tae

excuse," insisted Jamie, who was in great fettle that Sabbath; "the doctor

hes never been burdened wi’ fees, and a’m judgin’ he coonted a wumman’s

gratitude that he saved frae weedowhood the best he ever got."

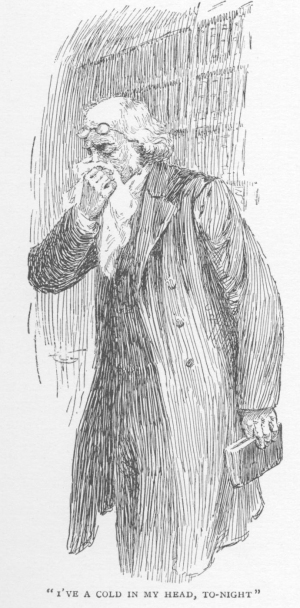

"A’ gaed up tae the Manse

last nicht," concluded Drumsheugh," and telt the minister hoo the doctor

focht aucht oors for Saunders’ life, an’ won, and ye never saw a man sae

carried. He walkit up and doon the room a’ the time, and every other

meenut he blew his nose like a trumpet.

"’I’ve

a cold in my head to-night, Drumsheugh,’ says he; ‘never mind me.’"

"’I’ve

a cold in my head to-night, Drumsheugh,’ says he; ‘never mind me.’"

"A’ve hed the same masel in

sic circumstances; they come on sudden," said Jamie.

"A’ wager there ‘ill be a

new bit in the laist prayer the day, an’ somethin’ worth hearin’."

And the fathers went into

kirk in great expectation.

"We beseech Thee for such

as be sick, that Thy hand may be on them for good, and that Thou wouldst

restore them again to health and strength," was the familiar petition of

every Sabbath.

The congregation waited in

a silence that might be heard, and were not disappointed that morning, for

the minister continued:

"Especially we tender Thee

hearty thanks that Thou didst spare Thy servant who was brought down into

the dust of death, and hast given him back to his wife and children, and

unto that end didst wonderfully bless the skill of him who goes out and in

amongst us, the beloved physician of this parish and adjacent districts."

"Didna a’ tell ye, neeburs?"

said Jamie, as they stood at the kirkyard gate before dispersing; "there’s

no a man in the coonty cud hae dune it better. ‘Beloved physician,’ an’

his ‘skill,’ tae, an’ bringing in ‘adjacent districts’ that’s Glen Urtach;

it wes handsome, and the doctor earned it, ay, every word.

"It’s an awfu’ peety he

didna hear yon; but dear knows whar he is the day, maist likely up—"

Jamie stopped suddenly at

the sound of a horse’s feet, and there, coming down the avenue of beech

trees that made a long vista from the kirk gate, they saw the doctor and

Jess.

One thought flashed through

the minds of the fathers of the commonwealth.

It ought to be done as he

passed, and it would be done if it were not Sabbath. Of course it was out

of the question on Sabbath.

The doctor is now

distinctly visible, riding after his fashion.

There was never such a

chance, if it were only Saturday; and each man reads his own regret in his

neighbor’s face.

The doctor is nearing them

rapidly; they can imagine the shepherd’s tartan.

Sabbath o’r no Sabbath, the

Glen cannot let him pass without some tribute of their pride.

Jess had recognized

friends, and the doctor is drawing rein.

"It hes tae be dune," said

Jamie desperately, "say what ye like." Then they all looked towards him,

and Jamie led.

"Hurrah," swinging his

Sabbath hat in the air, "hurrah," and once more, "hurrah," Whinnie Knowe,

Drumsheugh, and Hillocks joining lustily, but Tammas Mitchell carrying all

before him, for he had found at last an expression for his feelings that

rendered speech unnecessary.

It was a solitary

experience for horse and rider, and Jess bolted without delay. But the

sound followed and surrounded them, and as they passed the corner of the

kirkyard, a figure waved his college cap over the wall and gave a cheer on

his own account.

"God bless you, doctor, and

well done."

"If it isna the minister,"

cried Drumsheugh, "in his goon an’ bans; tae think o’ that; but a’ respeck

him for it."

Then Drumtochty became

self-conscious, and went home in confusion of face and unbroken silence,

except Jamie Soutar, who faced his neighbors at the parting of the ways

without shame.

"A’ wud dae it a’ ower

again if a’ hed the chance; he got naethin’ but his due."

It was two miles before

Jess composed her mind, and the doctor and she could discuss it quietly

together.

"A’ can hardly believe ma

ears, Jess, an’ the Sabbath tae; their verra jidgment hes gane frae the

fouk o’ Drumtochty.

"They’ve heard about

Saunders, a’m thinkin’, wumman, and they’re pleased we brocht him roond;

he’s fairly on the mend, ye ken, noo.

"A’ never expeckit the like

o’ this, though, and it wes juist a wee thingie mair than a’ cud hae stude

"Ye hev yir share in’t tae,

lass; we’ve hed mony a hard nicht and day thegither, an’ yon wes oor

reward. No mony men in this warld ‘ill ever get a better, for it cam frae

the hert o’ honest fouk."