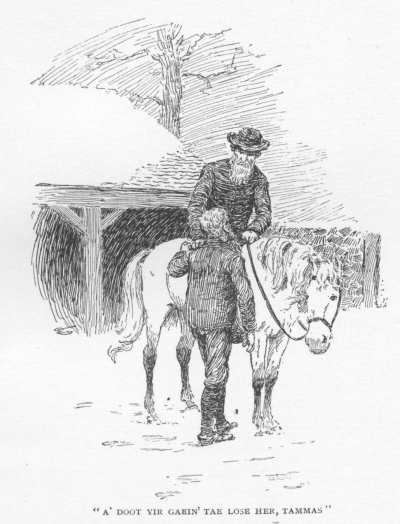

"Is’t as bad as yir lookin’,

doctor? tell’s the truth; wull Annie no come through?" and Tammas looked

MacLure straight in the face, who never flinched his duty or said smooth

things.

"A’

wud gie onything tae say Annie hes a chance, but a’ daurna; a’ doot yir

gaein’ tae lose her, Tammas."

"A’

wud gie onything tae say Annie hes a chance, but a’ daurna; a’ doot yir

gaein’ tae lose her, Tammas."

MacLure was in the saddle,

and as he gave his judgment, he laid his hand on Tammas’s shoulder with

one of the rare caresses that pass between men.

"It’s a sair business, but

ye ‘ill play the man and no vex Annie; she ‘ill dae her best, a’ll

warrant."

"An’ a’ll dae mine," and

Tammas gave MacLure’s hand a grip that would have crushed the bones of a

weakling. Drumtochty felt in such moments the brotherliness of this

rough-looking man, and loved him.

Tammas hid his face in

Jess’s mane, who looked round with sorrow in her beautiful eyes, for she

had seen many tragedies, and in this silent sympathy the stricken man

drank his cup, drop by drop.

"A’

wesna prepared for this, for a’ aye thocht she wud live the langest. . .

She’s younger than me by ten years, and never wes ill. . . . We’ve been

mairit twal year laist Martinmas, but it’s juist like a year the day. . .

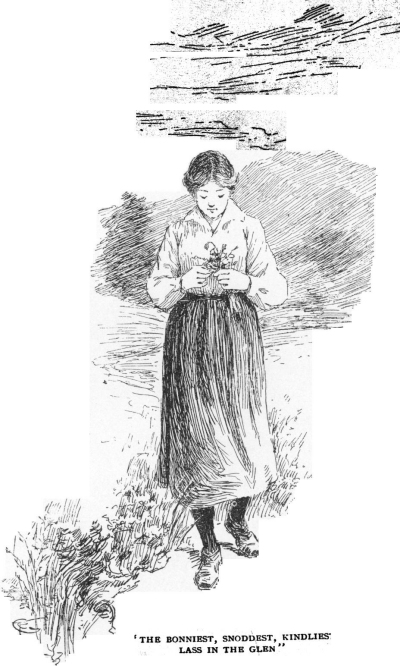

.A’ wes never worthy o’ her, the bonniest, snoddest (neatest), kindliest

lass in the Glen. . . . A’ never cud mak oot hoo she ever lookit at me,

‘at hesna hed ae word tae say aboot her till it’s ower late. . . . She

didna cuist up tae me that a’ wesna worthy o’ her, no her, but aye she

said, ‘Yir ma ain gudeman, and nane cud be kinder tae me.’. . . . An’ a’

wes minded tae be kind, but a’ see noo mony little trokes a’ micht hae

dune for her, and noo the time is bye. . . . Naebody kens hoo patient she

wes wi’ me, and aye made the best o ‘me, an’ never pit me tae shame afore

the fouk. . . . An’ we never hed ae cross word, no ane in twal year. . .

.We were mair nor man and wife, we were sweethearts a’ the time. . . . Oh,

ma bonnie lass, what ‘ill the bairnies an’ me dae withoot ye, Annie?"

"A’

wesna prepared for this, for a’ aye thocht she wud live the langest. . .

She’s younger than me by ten years, and never wes ill. . . . We’ve been

mairit twal year laist Martinmas, but it’s juist like a year the day. . .

.A’ wes never worthy o’ her, the bonniest, snoddest (neatest), kindliest

lass in the Glen. . . . A’ never cud mak oot hoo she ever lookit at me,

‘at hesna hed ae word tae say aboot her till it’s ower late. . . . She

didna cuist up tae me that a’ wesna worthy o’ her, no her, but aye she

said, ‘Yir ma ain gudeman, and nane cud be kinder tae me.’. . . . An’ a’

wes minded tae be kind, but a’ see noo mony little trokes a’ micht hae

dune for her, and noo the time is bye. . . . Naebody kens hoo patient she

wes wi’ me, and aye made the best o ‘me, an’ never pit me tae shame afore

the fouk. . . . An’ we never hed ae cross word, no ane in twal year. . .

.We were mair nor man and wife, we were sweethearts a’ the time. . . . Oh,

ma bonnie lass, what ‘ill the bairnies an’ me dae withoot ye, Annie?"

The winter night was

falling fast, the snow lay deep upon the ground, and the merciless north

wind moaned through the close as Tammas wrestled with his sorrow dry-eyed;

for tears were denied Drumtochty men. Neither the doctor nor Jess moved

hand or foot, but their hearts were with their fellow creatures, and at

length the doctor made a sign to Marget Howe, who had come out in search

of Tammas, and now stood by his side.

"Dinna mourn tae the brakin’

o’ yir hert, Tammas," she said, "as if Annie an’ you hed never luved.

Neither death nor time can pairt them that luve; there’s naethin’ in a’

the warld sae strong as luve. If Annie gaes frae the sichot ‘yir cen she

‘ill come the nearer tae yir hert. She wants tae see ye, and tae hear ye

say that ye ‘ill never forget her nicht nor day till ye meet in the land

where there’s nae pairtin’. Oh, a’ ken saying’, for it’s five year noo sin

George gied awa, an’ he’s mair wi’ me noo than when he wes in Edinboro’

and I was in Drumtochty."

"Thank ye kindly, Marget;

thae are gude words and true, an’ ye hev the richt tae say them; but a’

canna dae without seein’ Annie comin’ tae meet me in the gloamin’, an’

gaein’ in an’ oot the hoose, an’ hearin’ her ca’ me by ma name, an’ a’ll

no can tell her a’ luve her when there’s nae Annie in the hoose.

"Can naethin’ be dun;

doctor? Ye savit Flora Cammil, and young Burnbrae, an’ yon shepherd’s wife

Dunleith wy, an’ we were a sae prood o’ ye, an’ pleased tae think that ye

hed keepit deith frae anither hame. Can ye no think o’ somethin’ tae help

Annie, and gie her back tae her man and bairnies?" and Tammas searched the

doctor’s face in the cold, weird light.

"There’s nae pooer on

heaven or airth like luve," Marget said to me afterwards; it maks the weak

strong and the dumb tae speak. Oor herts were as water afore Tammas’s

words, an’ a’ saw the doctor shake in his saddle. A’ never kent till that

meenut hoo he hed a share in a’body’s grief, an’ carried the heaviest

wecht o’ a’ the Glen. A’ peetied him wi’ Tammas lookin’ at him sae

wistfully, as if he hed the keys o’ life an’ deith in his hands. But he

wes honest, and wudna hold oot a false houp tae deceive a sore hert or win

escape for himsel’."

"Ye needna plead wi’ me,

Tammas, to dae the best a’ can for yir wife. Man, a’ kent her lang afore

ye ever luved her; a’ brocht her intae the warld, and a’ saw her through

the fever when she wes a bit lassikie; a’ closed her mither’s een, and it

was me hed tae tell her she wes an orphan, an’ nae man wes better pleased

when she got a gude husband, and a’ helpit her wi’ her fower bairns. A’ve

naither wife nor bairns o’ ma own, an’ a’ coont a’ the fouk o’ the Glen ma

family. Div ye think a’ wudna save Annie if I cud? If there wes a man in

Muirtown ‘at cud dae mair for her, a’d have him this verra nicht, but a’

the doctors in Perthshiire are helpless for this tribble.

"Tammas, ma puir fallow, if

it could avail, a’ tell ye a’ wud lay doon this auld worn-oot ruckle o’ a

body o’ mine juist tae see ye baith sittin’ at the fireside, an’ the

bairns roond ye, couthy an’ canty again; but it’s no tae be, Tammas, it’s

no tae be."

"When a’ lookit at the

doctor’s face," Marget said, "a’ thocht him the winsomest man a’ ever saw.

He was transfigured that nicht, for a’m judging there’s nae

transfiguration like luve."

"It’s God’s wull an’ maun

be borne, but it’s a sair wull for me, an’ a’m no ungratefu’ tae you,

doctor, for a’ ye’ve dune and what ye said the nicht," and Tammas went

back to sit with Annie for the last time.

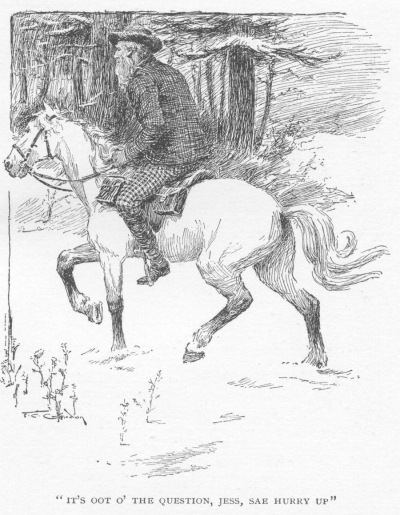

Jess picked her way through

the deep snow to the main road, with a skill that came of long experience,

and the doctor held converse with her according to his wont.

"Eh, Jess wumman, yon wes

the hardest wark a’ hae tae face, and a’ wud raither hae ta’en ma chance

o’ anither row in a Glen Urtach drift than tell Tammas Mitchell his

wife wes deein’.

"A’ said she cudna be

cured, and it wes true, for there’s juist ae man in the land fit for’t,

and they micht as weel try tae get the mune oot o’ heaven. Sae a’ said

naethin’ tae vex Tammas’s hert, for it’s heavy eneuch withoot regrets.

"But it’s hard, Jess, that

money wull buy life after a’, an’ if Annie wes a duchess her man wudna

lose her; but bein’ only a puir cottar’s wife, she maun dee afore the

week’s oot.

"Gin we hed him the morn

there’s little doot she would be saved, for he hesna lost mair than five

per cent. o’ his cases, and they, ‘ill be puir toon’s craturs, no strappin

women like Annie.

"It’s

oot o’ the question, Jess, sae hurry up, lass, for we’ve hed a heavy day.

But it wud be the grandest thing that was ever dune in the Glen in oor

time if it could be managed by hook or crook.

"It’s

oot o’ the question, Jess, sae hurry up, lass, for we’ve hed a heavy day.

But it wud be the grandest thing that was ever dune in the Glen in oor

time if it could be managed by hook or crook.

"We ‘ill gang and see

Drumsheugh, Jess; he’s anither man sin’ Geordie Hoo’s deith, and he wes

aye kinder than fouk kent;" and the doctor passed at a gallop through the

village, whose lights shone across the white frost-bound road.

"Come in by, doctor; a’

heard ye on the road; ye ‘ill hae been at Tammas Mitchell’s; hoo’s the

gudewife? a’ doot she’s sober."

"Annie’s deein’, Drumsheugh,

an’ Tammas is like tae brak his hert."

"That’s no lichtsome,

doctor, no lichtsome ava, for a’ dinna ken ony man in Drumtochty sae bund

up in his wife as Tammas, and there’s no a bonnier wumman o’ her age

crosses our kirk door than Annie, nor a cleverer at her wark. Man, ye ‘ill

need tae pit yir brains in steep. Is she clean beyond ye?"

"Beyond

me and every ither in the land but ane, and it wud cost a hundred guineas

tae bring him tae Drumtochty."

"Beyond

me and every ither in the land but ane, and it wud cost a hundred guineas

tae bring him tae Drumtochty."

"Certes he’s no blate; it’s

a fell chairge for a short day’s work; but hundred or no hundred we’ll hae

him, an’ no let Annie gang, and her no half her years."

"Are ye meanin’ it,

Drumsheugh?" and MacLure turned white below the tan.

"William MacLure," said

Drumsheugh, in one of the few confidences that ever broke the Drumtochty

reserve, "a’m a lonely man, wi’ naebody o’ ma ain blude tae care for me

livin’, or tae lift me intae ma coffin when a’m deid.

"A’ fecht awa at Muirtown

market for an extra pound on a beast, or a shillin’ on the quarter o’

barley, an’ what’s the gude o’t? Burnbrae gaes aff tae get a goon for his

wife or a buke for his college laddie, an’ Lachlan Campbell ‘ill no leave

the place noo without a ribbon for Flora.

"Ilka man in the Kildrummie

train has some bit fairin’ his pooch for the fouk at hame that he’s bocht

wi’ the siller he won.

"But there’s naebody tae be

lookin’ oot for me, an’ comin’ doon the road tae meet me, and daffin’

(joking) ivi’ me about their fairing, or feeling ma pockets. Ou ay, a’ve

seen it a’ at ither hooses, though they tried tae hide it frae me for fear

a’ wud lauch at them. Me lauch, wi’ ma cauld, empty hame!

"Yir the only man kens,

Weelum, that I aince luved the noblest wumman in the glen or onywhere, an’

a’ luve her still, but wi’ anither luve noo.

"She had given her heart

tae anither, or a’ve thocht a’ micht hae won her, though nae man be worthy

o’ sic a gift. Ma hert turned tae bitterness, but that passed awa beside

the brier bush what George Hoo lay yon sad simmer time. Some day a’ll tell

ye ma story, Weelum, for you an’ me are auld freends, and will be till we

dee."

MacLure felt beneath the

table for Drumsheugh’s hand, but neither man looked at the other.

"Weel, a’ we can dae noo,

Weelum, gin we haena mickle brichtness in oor ain hames, is tae keep the

licht frae gaein’ oot in anither hoose. Write the telegram, man, and Sandy

‘ill send it aff frae Kildrummie this verra nicht, and ye ‘ill hae

yir man the morn."

"Yir the man a’ coonted ye,

Drumsheugh, but ye ‘ill grant me ae favor. Ye ‘ill lat me pay the half,

bit by bit—a’ ken yir wullin’ tae dae’t a’—but a’ haena mony pleasures,

an’ a’ wud like tae hae ma ain share in savin’ Annie’s life."

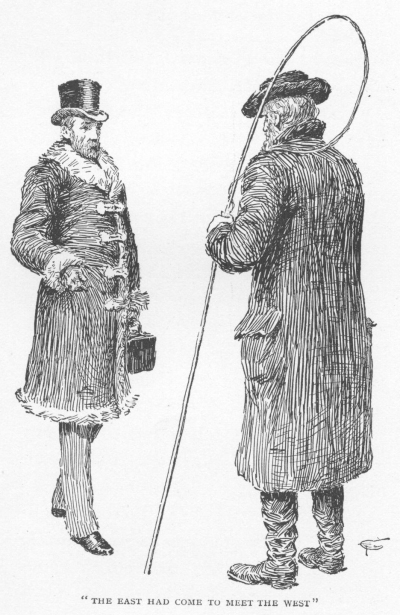

Next

morning a figure received Sir George on the Kildrummie platform, whom that

famous surgeon took for a gillie, but who introduced himself as "MacLure

of Drumtochty." It seemed as if the East had come to meet the West when

these two stood together, the one in travelling furs, handsome and

distinguished, with his strong, cultured face and carriage of authority, a

characteristic type of his profession; and the other more marvellously

dressed than ever, for Drumsheugh’s topcoat had been forced upon him for

the occasion, his face and neck one redness with the bitter cold; rough

and ungainly, yet not without some signs of power in his eye and voice,

the most heroic type of his noble profession. MacLure compassed the

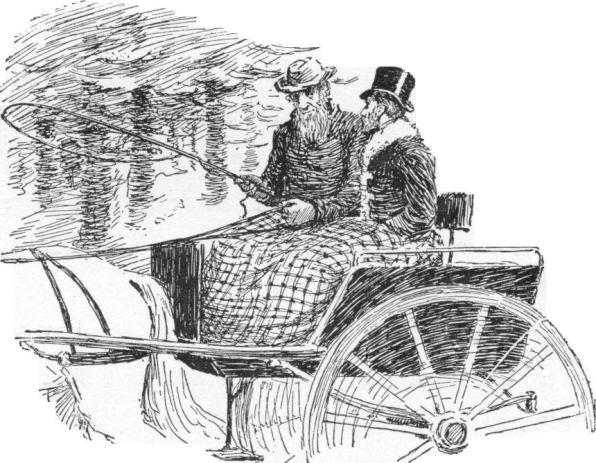

precious arrival with observances till he was securely seated in

Drumsheugh’s dog cart—a vehicle that lent itself to history—with two

full-sized plaids added to his equipment—Drumsheugh and Hillocks had both

been requistioned—and MacLure wrapped another plaid round a leather case,

which was placed below the seat with such reverence as might be given to

the Queen’s regalia. Peter attended their departure full of interest, and

as soon as they were in the fir woods MacLure explained that it would be

an eventful journey.

Next

morning a figure received Sir George on the Kildrummie platform, whom that

famous surgeon took for a gillie, but who introduced himself as "MacLure

of Drumtochty." It seemed as if the East had come to meet the West when

these two stood together, the one in travelling furs, handsome and

distinguished, with his strong, cultured face and carriage of authority, a

characteristic type of his profession; and the other more marvellously

dressed than ever, for Drumsheugh’s topcoat had been forced upon him for

the occasion, his face and neck one redness with the bitter cold; rough

and ungainly, yet not without some signs of power in his eye and voice,

the most heroic type of his noble profession. MacLure compassed the

precious arrival with observances till he was securely seated in

Drumsheugh’s dog cart—a vehicle that lent itself to history—with two

full-sized plaids added to his equipment—Drumsheugh and Hillocks had both

been requistioned—and MacLure wrapped another plaid round a leather case,

which was placed below the seat with such reverence as might be given to

the Queen’s regalia. Peter attended their departure full of interest, and

as soon as they were in the fir woods MacLure explained that it would be

an eventful journey.

"It’s a richt in here, for

the wind disna get at the snaw, but the drifts are deep in the Glen, and

th’ill be some engineerin’ afore we get tae oor destination."

Four times they left the

road and took their way over fields, twice they forced a passage through a

slap in a dyke, thrice they used gaps in the paling which MacLure had made

on his downward journey.

"A’ seleckit the road this

mornin’, an’ a’ ken the depth tae an inch; we ‘ill get through this

steadin’ here tae the main road, but oor worst job ‘ill be crossin’ the

Tochty.

"Ye see the bridge hes been

shaken wi’ this winter’s flood, and we daurna venture on it, sae we hev

tae ford, and the snaw’s been melting up Urtach way. There’s nae doot the

water’s gey big, and it’s threatenin’ tae rise, but we ‘ill win through wi’

a warstle.

"It micht be safer tae lift

the instruments oot o’ reach o’ the water; wud ye mind haddin’ them on yir

knee till we’re ower, an’ keep firm in yir seat in case we come on a stane

in the bed o’ the river."

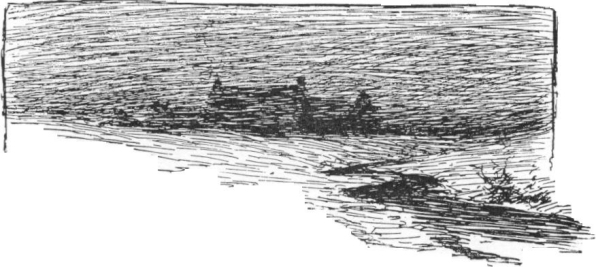

By this time they had come

to the edge, and it was not a cheering sight. The Tochty had spread out

over the meadows, and while they waited they could see it cover another

two inches on the trunk of a tree. There are summer floods, when the water

is brown and flecked with foam, but this was a winter flood, which is

black and sullen, and runs in the centre with a strong, fierce, silent

current. Upon the opposite side Hillocks stood to give directions by word

and hand, as the ford was on his land, and none knew the Tochty better in

all its ways.

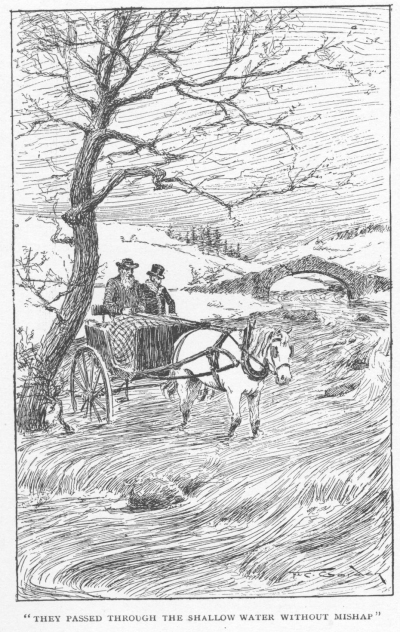

They

passed through the shallow water without mishap, save when the wheel

struck a hidden stone or fell suddenly into a rut; but when they neared

the body of the river MacLure halted, to give Jess a minute’s breathing.

They

passed through the shallow water without mishap, save when the wheel

struck a hidden stone or fell suddenly into a rut; but when they neared

the body of the river MacLure halted, to give Jess a minute’s breathing.

"It ‘ill tak ye a’ yir

time, lass, an’ a’ wud raither be on yir back; but ye never failed me yet,

and a wumman’s life is hangin’ on the crossin’."

With the first plunge into

the bed of the stream the water rose to the axles, and then it crept up to

the shafts, so that the surgeon could feel it lapping in about his feet,

while the dogcart began to quiver, and it seemed as if it were to be

carried away. Sir George was as brave as most men, but he had never forded

a Highland river in flood, and the mass of black water racing past

beneath, before, behind him, affected his imagination and shook his

nerves. He rose from his seat and ordered MacLure to turn back, declaring

that he would be condemned utterly and eternally if he allowed himself to

be drowned for any person.

"Sit doon," thundered

MacLure; "condemned ye will be suner or later gin ye shirk yir duty, but

through the water ye gang the day."

Both men spoke much more

strongly and shortly, but this is what they intended to say, and it was

MacLure that prevailed.

Jess trailed her feet along

the ground with cunning art, and held her shoulder against the stream;

MacLure leant forward in his seat, a rein in each hand, and his eyes fixed

on Hillocks, who was now standing up to the waist in the water, shouting

directions and cheering on horse and driver.

"Haud tae the richt,

doctor; there’s a hole yonder. Keep oot o’t for ony sake. That’s it; yir

daein’ fine. Steady, man, steady. Yir at the deepest; sit heavy in yir

seats. Up the channel noo, and ye’11 be oot o’ the swirl. Weel dune, Jess,

weel dune, auld mare! Mak straicht for me, doctor, an’ a’ll gie ye the

road oot. Ma word, ye’ve dune yir best, baith o’ ye this mornin’," cried

Hillocks, splashing up to the dogcart, now in the shallows.

"Sall, it wes titch an’ go

for a meenut in the middle; a Hielan’ ford is a kittle (hazardous) road in

the snaw time, but ye’re safe noo.

"Gude luck tae ye up at

Westerton, sir; nane but a richt-hearted man wud hae riskit the Tochty in

flood. Ye’re boond tae succeed aifter sic a graund beginnin’," for it had

spread already that a famous surgeon had come to do his best for Annie,

Tammas Mitchell’s wife.

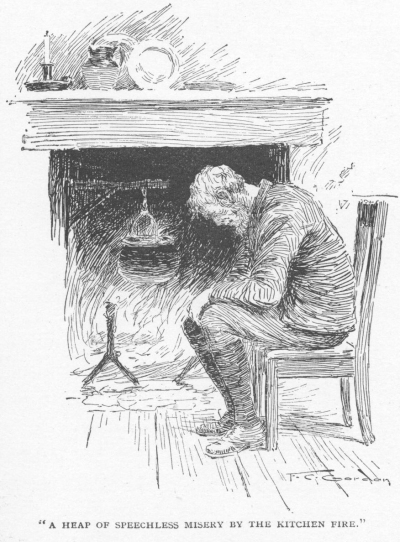

Two

hours later MacLure came out from Annie’s room and laid hold of Tammas, a

heap of speechless misery by the kitchen fire, and carried him off to the

barn, and spread some corn on the threshing floor and thrust a flail into

his hands.

Two

hours later MacLure came out from Annie’s room and laid hold of Tammas, a

heap of speechless misery by the kitchen fire, and carried him off to the

barn, and spread some corn on the threshing floor and thrust a flail into

his hands.

"Noo we’ve tae begin, an’

we ‘ill no be dune for an’ oor, and ye’ve tae lay on withoot stoppin’ till

a’ come for ye, an’ a’ll shut the door tae haud in the noise, an’ keep yir

dog beside ye, for there maunna be a cheep aboot the hoose for Annie’s

sake."

"A’ll dae onything ye want

me, but if— if--"

"A’ll come for ye, Tammas,

gin there be danger; but what are ye feared for wi’ the Queen’s ain

surgeon here?"

Fifty minutes did the flail

rise and fall, save twice, when Tammas crept to the door and listened, the

dog lifting his head and whining.

It seemed twelve hours

instead of one when the door swung back, and MacLure filled the doorway,

preceded by a great burst of light, for the sun had arisen on the snow.

His face was as tidings of

great joy, and Elspeth told me that there was nothing like it to be seen

that afternoon for glory, save the sun itself in the heavens.

"A’ never saw the marrow

o’t, Tammas, an’ a’ll never see the like again; it’s a’ ower, man, withoot

a hitch frae beginnin’ tae end, and she’s fa’in’ asleep as fine as ye

like.’’

"Dis he think Annie . . .

‘ill live?"

"Of coorse he dis, and be

aboot the hoose inside a month; that’s the gud o’ bein’ a clean-bluided,

weel-livin’—"

"Preserve ye, man, what’s

wrang wi’ ye? it’s a mercy a’ keppit ye, or we wud hey hed anither job for

Sir George.

"Ye’re a richt noo; sit

doon on the strae. A’ll come back in a whilie, an’ ye i’ll see Annie juist

for a meenut, but ye maunna say a word."

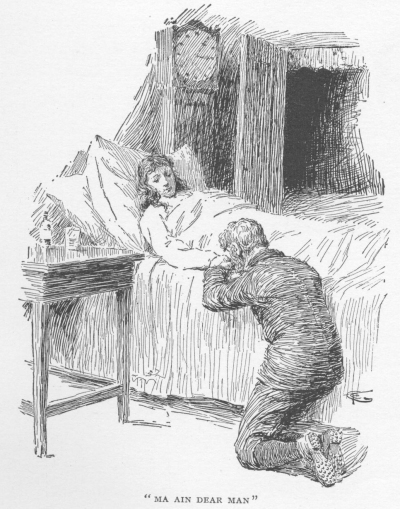

Marget took him in and let

him kneel by Annie’s bedside.

He

said nothing then or afterwards, for speech came only once in his lifetime

to Tammas, but Annie whispered, "Ma ain dear man."

He

said nothing then or afterwards, for speech came only once in his lifetime

to Tammas, but Annie whispered, "Ma ain dear man."

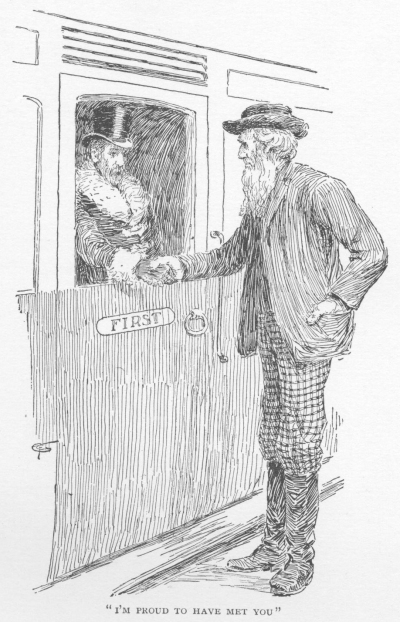

When the doctor placed the

precious bag beside Sir George in our solitary first next morning, he laid

a cheque beside it and was about to leave.

"No, no," said the great

man. "Mrs. Macfayden and I were on the gossip last night, and I know the

whole story about you and your friend.

"You have some right to

call me a coward, but I’ll never let you count me a mean, miserly rascal,"

and the cheque with Drumsheugh’s painful writing fell in fifty pieces on

the floor.

As the train began to move,

a voice from the first called so that all the station heard.

"Give’s another shake of

your hand, MacLure; I’m proud to have met you; you are an honor to our

profession. Mind the antiseptic dressings."

It

was market day, but only Jamie Soutar and Hillocks had ventured down.

It

was market day, but only Jamie Soutar and Hillocks had ventured down.

"Did ye hear yon, Hillocks?

hoo dae ye feel? A’ll no deny a’m lifted."

Halfway to the Junction

Hillocks had recovered, and began to grasp the situation.

"Tell’s what he said. A’

wud like to hae it exact for Drumsheugh."

"Thae’s the eedentical

words, an’ they’re true; there’s no a man in Drumtochty disna ken that,

except ane."

"An’ wha’s thar, Jamie ?"

"It’s Weelum MacLure himsel.

Man, a’ve often girned that he sud fecht awa for us a’, and maybe dee

before he kent that he hed githered mair luve than ony man in the Glen.

"‘A’m prood tae hae met

ye’, says Sir George, an’ him the greatest doctor in the land. ‘Yir an

honor tae oor profession.’

"Hillocks, a’ wudna hae

missed it for twenty notes," said James Soutar, cynic-in-ordinary to the

parish of Drumtochty.