|

At the very time that Dick

was writing the preceding letter to his sister, a circumstance occurred

which brought him almost to the verge of ruin.

He had ordered from his flour merchants at Leith twenty-three bags of fine

flour. They were shipped by the steamer “Prince Consort” in the month of

March 1863. The steamers from Leith to Thurso usually call at Aberdeen and

Wick on their way northward. On entering the harbour of Aberdeen, the

“Prince Consort” struck the platform, and ran along the North Pier, where

the passengers were taken off. It must have been a lubberly affair, as there

was no heavy sea on at the time. It was said that the person who steered the

ship was half-drunk.

When the passengers were taken off, it was attempted to float away the

vessel, but as the tide was ebbing, that could not be done. The sea

eventually broke her in two. The water entered the hold; and, though part of

the cargo was saved, Dick’s flour was thoroughly drenched.

The ship was insured, but Dick’s flour was not. Though the bill of lading

intimated that the flour was to be delivered in good order—“the act of God,

the Queen’s enemies, fire, and all and every other dangers and accidents of

the seas excepted”— yet it was found difficult to prove that the disaster

occurred through the negligence of those who managed the vessel. Those whose

goods had been lost or damaged had therefore to sustain the loss. To Dick it

was ruinous.

The cost of the flour was only £45 :13 :6; but, small though the sum was,

Dick had not the money at his command. What was he to do? He had never been

in debt in his life. And yet, not only must this debt be paid for, but he

must order more flour in order to carry on his business. He had been slowly

going to ruin for years past. He had lost £120 of his former savings; and

now, to use his own words, the loss of £45 made him “next thing to a

beggar.” His only property consisted in his books, his collection of fossil

fishes, his botanical specimens, his slender stock of furniture, his

old-fashioned clothes, and his little store of linen. These were of little

value. They could not be sold in time to save him. He must turn to some one

else. Then he bethought him of his affectionate, generous-hearted sister.

She had offered him money a few years before, which he had refused, because

“coddling and nursing was about the worst treatment imaginable.”

But alas! the time had come when he could no longer refuse her generous

offer. He wrote to her, pouring out his griefs, and telling her how he had

been reduced almost to the brink of ruin.

“Have you still,” lie asked, “that spare money? Would you be willing to lend

it to me in hope of getting it back again? Should you wish it, I would pay

you interest for it. I have long felt the necessity of getting away out of

this miserable place. There is no trade, and the risk is very great. I have

had a sore struggle, and have often been sadly grieved; but this is the

saddest ill that has ever come to me. ... I am injured for ever. I’ll never

make an extra farthing by my trade here. The bakers are in swarms now. I am

old, and my strength and sight fail me. Before, I had hardships quite

enough; but now, this crowns everything. I am stupid with grief."

Dick’s sister earnestly sympathised with him. She told him to cheer up—to

put his shoulder again to the wheel, and that all might yet go well with

him. She sent him £20 of her spare money. She did so at considerable

sacrifice, as she required the money at that time for special purposes. But

she could not stand the piteous entreaties of her brother, and sacrificed

her own requirements for his good.

Dick plucked up heart again. He replied to his sister: “I am not easily put

down. I am neither inactive nor desponding. I am trying a way of recovering

my loss. Your brother Robert is the most active and laborious person in the

county, and could not live in idleness for one week. He does not entertain a

single thought of being beat.”

The “way of recovering his loss,” to which Dick alluded, was by selling his

fossils. He had now a very fine collection; but when such things are offered

in the market, they are likely to bring very little indeed. Still, he was of

opinion that if his collection was offered to some scientific man, he might

be able to realise enough to pay his debts.

One of Dick’s geological friends was Mr. John Miller, E.G.S., a gentleman of

independent property. He belonged to Thurso, but lived for the most part in

London. He had a great respect for Dick, and took a deep interest in his

fossil researches. When at Thurso, Mr. Miller was a frequent visitor at the

bakehouse, and had many keen discussions with Robert Dick and Charles Peach

about geological subjects. He was himself a collector, and employed a Mr.

Budge to obtain for him new specimens of fossil fishes. He often consulted

Dick as to their interest and value.

When the thought occurred to Dick of selling his fossils to Mr.

Miller—knowing that he was buying them from Budge—he addressed to him the

following letter :—

“Some years since you saw that I was distressed, and you offered to relieve

me. I put your proffered kindness aside. Since then you have had many

opportunities of knowing and seeing me; and I think you will allow that

anything like complaining was very far from me. A recent event, however, has

ruined me. The ‘Prince Consort,’ on attempting to enter Aberdeen Harbour,

has become a total wreck. I had flour on her, uninsured, to the amount of

£45 :13 : 6.

“Enclosed is a note to Sir Roderick Murchison, stating the matter, and

promising to send him every Old Red fossil in my possession, if he would in

pity undertake to do anything among the London geologists by way of making

up my loss. Will you in kindness hand my note to him in a quiet way, and I

will be ever grateful to you? If you dislike handing my note to Sir

Roderick, put it in the fire, and also this one to yourself.”

We have not Mr. Miller’s reply to Dick’s letter. Very likely it may have

been intended to cheer him up. At all events it seems to have contained some

reference to Dick’s “independence,” for here is Dick’s reply, 27th March

1863 :—

“It is all very good to talk to me about 'independence.’ I have laboured

among flour bags for the last thirty-eight years, but I never yet knew an

empty bag to stand upright. .

“An honest well-meaning man once kept his horse on short allowance, and

boasted that he had brought him to live on a straw a day. But when he had

accomplished his object, the horse died.

“A very kind and a very discerning public have, for the last eighteen years,

set me down as independent, and fed me with chopped straw; and now those

drunken blackguards of the steamer have ruined me. I am a beggar, not in

word, but in fact.

“Previous to writing to you, I applied to my sister at Haddington. She at

one time offered me £48. I would not take the money. I thought that she

might still have it. She wrote at once, saying that she had it yet, but was

about to use it. I told her never to mind me, and just to use it in the way

intended. She replied again, and sent me £20.

“The steamer people have sent me twelve bags, out of twenty-three bags of my

flour. I have laboured hard and sifted it out, and made out six hags of

spoilt flour! With my sister’s £20, and with what the flour may do, and

perhaps other resources, I will try and manage to pay my bill.

“You will please to give orders to the National Bank accordingly. Reverse

your order I have not gone to the bank, and do not intend to go on the

errand you speak of.

“As to my relations with Sir Roderick Murchison, I am already his debtor for

two hundred dried plants, and rather than he turned out on the wide world, I

would not hesitate one moment in being indebted to his goodness still

further.”

He followed this letter with another written on the next day:—

“On trial,” he said, “I find that the flour saved, after much labour, is

mixed with sand; consequently it will have to go for little or nothing.

“In my last to you, I thought that I would get on without troubling any one;

but now I find it all hopeless.

“I have written to Sir Roderick Murchison offering to sell my fossils. I

have asked his permission to send them up to Jennyn Street Museum, that he

might give for them whatever he thinks them worth.

“Surely there is no degradation in this idea It was altogether out of

the question to allow the amount of my loss to fall upon you. No! I will not

do that. But if you put in a good word for me with Sir Roderick about these

fossils, I shall feel grateful to you.

“The fossils are not many, but they are such as Sir Roderick has not in his

Museum.

“P.S.—If Sir Roderick Murchison declines to purchase my fossils, I’ll not be

beat, but will offer them to some other person.”

At last the matter was pleasantly settled. Mr. Miller at once agreed to

purchase the fossils, and sent Dick an order on the National Bank for

£46,—the amount of his loss by the shipwrecked flour. Dick cordially

acknowledged the receipt of Mr. Miller’s letter:—

“I thank you most sincerely. I have to-day (4th April) received a note from

Sir Roderick Murchison. He will take the fossils; but I have settled it in

my mind to give them to you. I am afraid that I grieved you by refusing your

gift, but I could not, poor as I am, take so much money for nothing. I will

give all my fossils to you—every one of them—shells of the boulder clay and

all. There are two or three which Hugh

Miller gave me, and these I will add to my own collection of fossils. I will

also give you all those which I had got for Professor Thomson, and my

blessing along with them.

“Of course £46 is too much for them; hut the fossils are worth—what they are

worth; and I must just be contented to stand indebted to your friendship for

the rest. I will label on the fossils the localities in which they were

found, and also pack them carefully.

“I am to write to Sir Roderick by this same post, telling him that you had

heard of my distress, that you had made a most liberal offer to me for the

fossils, and that I had given them to you. I know—at least I trust—that Sir

Roderick will see meet not to be offended at me for giving you the

preference. Sir Roderick will get plenty, and so will you. But one thing you

know, that some of my fossils are altogether rare, and not in the possession

of any other person.”

And thus ended the sale of Dick’s fossils. He parted with them with a heavy

heart. But he was now enabled to pay his bill for the lost flour, which he

did on the 29th of April following. How he regretted the loss of his fossils

may be inferred from a letter to his brother-in-law:—“Unhappily,” he said,

“I have now no fossils. I have given them all away. Alas! how often has my

heart beat proudly, when looking over the figures of jaws in Duff’s and Dr.

Buckland’s books, and saying, *O yes, these are very fine, but humble as I

am, I have finer than either.’ But that is over, and they are all away. They

exist only in remembrance, and I never hope to find the like again.”

Again he felt his business falling off. Unfortunately, he had tried to make

bread of the sifted flour saved from the wreck; hut the bread was not good,

and more customers left him. “They might have borne with me,” he said, “a

little longer, if they had only known of my suffering and distress.”

Afterwards, he said, “If I had only half as much work as I could do, I

should be the happiest of men. I have more biscuit beside me than I shall be

able to sell in three months. I would toil willingly, but all is overdone

here. It is very difficult to get work at all. He is a happy man who can

make his living. Shoals of masons and house-wrights are leaving here by

steamer.

“Men are failing rapidly. One is said to have failed for £3000. He hasn’t

preached according to his stipend. You know the story. An elder went to his

minister, and said, ‘that his preaching was rather poor; that’s what people

said.’ *Of what do they complain?" asked the minister. *Weel, sir, they’re

saying that ye dinna preach half weel.’ *So,’ said the minister. *but ye

dinna consider that ye dinna pay half weel. I preach according to my

stipend. Pay me better, and I’ll preach better!’ And so, had the people

bought better, the merchant would have sold better, and not a breath would

have been heard about his failure.”

Though Dick said that his customers were leaving him, and that he was

thought less of than ever, there was still some comfort left him. “Nobody

heeds me,” he said; “and yet Nature is as kindly as ever.” The spring was

approaching. Fine balmy days wooed him to the fields, or led him along the

sea-shore. He watched nature with the eye of a lover. He longed for the

coming of spring; and when she came he was unspeakably glad. He looked

anxiously for every favourite plant, and knew it at once as it put its first

stem above the ground.

The spring was later in 1863. At the end of April the fertile stems of the

common Field Horsetail were not yet above ground. He had seen only one

rumpled straggler. Neither Drummond’s Horsetail, nor the Wood Horsetail, had

made their appearance. It was not until about the middle of May that he

found them above ground,—excepting Drummond’s Horsetail, which was always

late.

“I went out last Sabbath morning,” he said, “up the river-side, and found

the common Field Horsetail and Wood Horsetail. The Water Horsetail was by

the riverside. The prevailing flowers are dog-violets and yellow primroses.

I found about six specimens of a rare plant peculiar to the north. It is

Ajuga pyramidalis—a plant I have sent alive, as well as dried, to the south.

It is a great prize with botanists. Of course, I look on them now with very

different feelings from what I once did. I found also the early Purple

Orchis by sixes and sevens. Also a species of chickweed which I never saw

before. It is a larger and showy species. No other flowers have come up as

yet. But they will come. And when they come, short will be their stay, and

all will be again desolate.”

A few days later, he again goes up the river-side, and found and plucked

numerous specimens of the far-famed grass—Rierocliloe borealis. By this time

Dick had received communications from botanists in nearly every part of the

country, asking for dried specimens of the grass. He also went to the cliffs

on Dunnet Head, to his ferneries on Ben Dorery and the Reay hills, to see

how the ferns were growing that he had planted—ferns that would still be

growing when he and his friend Peach “were both out of time.”

“I have discovered,” he says one day, “another plant wonder! Some time ago I

found a new daisy. I have now found another. It has twenty-four little

heads, and the stalks are longer than the other. I sought all over the grass

field on which it grew, and could not find another. I never read of such a

daisy being found wild. A daisy with thirteen heads, and another with

twenty-four heads, are most extraordinary. But "little things are great to

little minds."

To his brother-in-law he said:—“So you have been amongst gardeners, and

found a daisy. Still, the wild one is, I think much finer. It is tall, and

being single, it makes a more natural show. I have hastily pencilled it off

[giving a drawing of the wild daisy]. I could have done it much better,—only

it is Saturday afternoon, and I am busy.

“The daisy is a great favourite with the poets; Burns speaks of it as the

'wee, modest, crimson-tipped flower.’ Another says of it, 'the bright

flower, whose home is everywhere.’ Another—

“The rose has but a summer reign,

The daisy never dies.

And still another :—

“Not worlds on worlds, in phalanx deep

Need we, to prove a God is here;

The daisy, fresh from winter’s sleep,

Tells of His Power in lines as clear.”

As far on as the month of June, the weather was cold and wet. There was a

good deal of hail, and one day of almost continuous snow. It is true, the

snow melted as it fell, and did no other harm than giving the grass a

brownish colour; though the country folks said the distant hills were

covered with snow.

Dick went to Loch Duran, some seven miles off, to see the Bullrush, rather a

rare plant in the far north; and besides the Lake Bullrush he found a much

rarer plant, the Lapland Beed. He could find the plant nowhere else. Six

miles inland he also found the Baltic Bush. “How it got there,” he said, “I

cannot make out.” He was recommended to try his hand among the marine

plants. “I have little doubt,” he observed, “that something new might be

discovered among the weeds along the sea-shore. Solomon says, ‘All things

are full of labour.’ But I’m ower auld for the labour, and as for the honour,

if I get a splitting headache and a sweating cough for my pains whilst

dabbling in a saltwater pool, perhaps the cost to me would be greater than

the honour. The poor animal is overladen already, and to put on more weight

would probably squeeze the life out of him altogether.”

“In fact,” he says to Mr. John Miller, “I fear that in pursuing researches

among the rocks I have not been half cautious; for during June I have been

suffering severely from rheumatism,—to an extent greater than ever I did

before. 'The vengeance ’ has got hold of both my feet,—so much so that I

have a difficulty in walking. That, you may be sure, was gloomy for me. I

grumbled to be compelled to walk slow, especially when the spirit within

said, Forward .”

And yet, when sufficiently well, Dick immediately went to the fields again

to gather ferns, grasses, plants, and wild roses. One day he says to his

brother-in-law, “I have had a ramble sixteen miles out and sixteen miles

home again for a small fern not so long as your little finger. I would not

have gone so far, but that the fern would not come to me. I had another

ramble twelve miles away and twelve miles home again, and all for nothing.

The plant I went to get was not growing for want of moisture.”

Dick had many applications for native roses. He sent a number of them to

Professor Babington of Cambridge; but he thought that the professor’s

opinion as to the species to which they belonged was not quite correct.

Writing to a friend he said, “The genus Rosa is a difficult one, even for

the most experienced botanist. It is hardly possible to tell the different

species by their leaves alone. Their fruit is a far better test. For

example, the leaves of the spiny or thorny rose may be found of various

sizes—from an eighth of an inch to more than an inch long. They differ so

much in their hairiness and smoothness that it would almost puzzle a

conjuror to define which was which. Some years since I sent a packet of dry

roses and leaves to Professor Balfour, who sent them to Professor Babington

in England. The latter gave the best verdict he could, and yet I have no

faith in it. For example, he told me that he believed one of them to he Rosa

involuta. Now, Rosa involuta is found in the Western Isles, and a stranger

might conclude readily enough that the plant grew in our neighbourhood. I

have ever since been watching the hush from which I took the specimen; hut I

cannot form any other opinion than that it is a variety only of the Rosa

spinosissima, or the Thorny Bose. The leaves of the said hush might pass for

the leaves of Rosa involuta, but the fruit will not. The fruit is invariably

the fruit of the Thorny Rose.”

In September 1863, Dick received a letter from Professor Owen, stating that

he had been informed that a large sperm whale had been cast ashore near

Thurso, and that, as he should like to secure the hones, he would feel

obliged to Mr. Dick if he would make the necessary inquiries about the

nature of the whale—whether it was a sperm whale or not. He added that Sir

Roderick Murchison had informed him that Mr. Dick was the most likely man in

Thurso to help him on the occasion.

It seems that the whale was cast ashore at Sandside, about thirteen miles

from Thurso. Dick worked all night with the object of starting on foot next

morning. But at two o’clock it began to rain, and it rained continuously for

about a fortnight. What with his pains and his rheumatism, he could scarcely

go out of doors during the interval. “Even if I went there,” he said, “it

would only have been—to guess. But I gathered all the information I could

get about the whale, and sent it to Professor Owen.”

Dick still kept up a considerable correspondence, though it was for the most

part forced upon him. He was indisposed, amidst his troubles, to open new

correspondence; though those who had corresponded with him once, would not

allow him to forget them: his letters were so interesting, humorous, and

instructive. He was often invited to pay visits far from home; but that was,

of course, impossible. Pew of his correspondents knew of his poverty. Very

likely, many of them thought him to be a man of independent position. Mr.

Notcutt of Cheltenham thought that Dick wished the correspondence with him

to cease. But he wrote to him again and again, until he replied. “I shall

ever feel grateful to you,” said Mr. Notcutt, “for the noble series of Old

Red fossils which, through your liberality, I possess. I append a list of

most of the things (dried flowering plants) which I have for you.” And at

length Dick was thawed into continuing the correspondence. Of course Mr.

Notcutt knew nothing of the pecuniary struggles that Dick was then passing

through.

Numerous requests were made to Dick for exchanges of plants and fossils.

Amongst his correspondence we find letters from Dr. L. Lindsay,

lichenologist, Perth; Mr. John Sim, botanist, Perth; Mr. Boy, botanist,

Aberdeen; Mr. Alfred Bell, Bloomsbury Street, London; Mr. John Backhouse,

York; Mr. Henry Coghill, Liverpool ; Mr. George Henslow, son of Professor

Henslow and from Mr. Tarrison of the Registrar-General’s Office, Melbourne.

The principal applications made to him were for fossils from the Old Red

Sandstone, and for specimens of the Hierochloe borealis which Dick had

discovered so many years before on the banks of the river Thurso. Mr.

Pringle of the Farmer's Gazette, Dublin, in acknowledging the receipt of a

specimen, addressed Dick in the following letter:—

“I gave the specimens of the Holy Grass to Dr. Moore of the Botanic Gardens.

He expressed himself much gratified with the same, and stated that he would

like to correspond with you. I send by book-post a copy of his Notes of a

Botanical Tour in Norway and Sweden, which will likely interest you. I must

repeat what I said to you—that I think it is a great pity, nay more, a

shame, that a man of your abilities and research should be buried alive, as

you are and have been. Why not come out as an author on those subjects with

which you are so conversant ? I hope yet to see Robert Dick’s name taking

its proper place among the list of British scientific men—far above the

names of some who occupy a large share of public attention, but whose chief

claim to notoriety consists in an unbounded command of cheek, and of a still

more unenviable gift of the gab.”

But it was too late for Robert Dick to give his thoughts to the world in

writing. Por one thing, he was too modest. He was about the last person to

wish to see his name in print. He was always complaining of the smallness of

his knowledge, even about subjects that he had studied the most. “The more I

know,” he said, “the more I feel my. ignorance. Knowledge seems to retreat

before me.” He often quoted the words of Athena's wisest son—“The most I

know is, nothing can he known.” And yet he said, “There is a satisfaction in

getting on in knowledge, which those only can imagine who have risen early

in searching for it.”

He still continued to write verses, probably as a relief from business

troubles. Mr. Peach says that he wrote verses down to the end of his life.

The following are extracted from some verses written in 1863, when in the

midst of his sorrow and poverty. The verses commence, “0 waft me o'er the

deep blue sea ! ” and proceed to the seventh stanza, which thus begins:—

“O waft me o’er, and let me roam

Her untilled plains, her fertile soil,

Where weary wanderers find a home,

And live by honest, manly toil!

By manly toil they rear a home—

Nor curst with want, nor crushed by care;

Nor grasping greed, nor grinding down,

Nor sad and weary struggle there.

“O waft me o’er! 0 waft me o’er!

In yon fair land there’s peace and rest,

And toiling-room for thousands more,

With blissful Hope to soothe the breast.

With grief, with care, by sorrows prest,

Of fruitless toil, my heart is sick.

O endless dreams, in horrors drest,

Of cruel want, when old and weak!

O waft me o’er! 0Owaft me o’er!

Yon slrip is strong; tlie sea is still;

Nor care I tliougli a tempest roar,

And every billow rolls a bill!

Let swelling sea-waves roar tbeir fill,

And dasb till crested wbite witb foam,

Tis sweet as murmuring mountain rill,

To sootbe a weary spirit Home.”

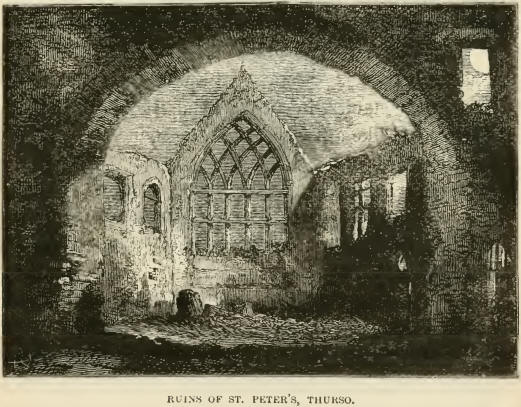

During his troubles Dick was a sleepless man. He wandered up and down the

little town at night, looking in at the little burying-ground of St.

Peter’s, where tbe fathers of Thurso lay buried. The town was asleep. Not a

footstep was to be beard, save those of the sleepless man plodding round the

graveyard, and from thence to his neighbouring bakehouse in Wilson’s Lane.

Night was always a time of thought for Dick. “It is so pleasant,” be says in

one of his letters, “getting up at nights to see the stars. Last night was

beautiful, and the moon was a great pleasure. It is impossible, when looking

at it, to prevent oneself falling into a dream of a far better world than

ours.”

“Do you know,” be said to his brother-in-law, “that I am a firm believer in

the unseen world? Millions of spiritual creatures walk the earth unseen,

both when we wake and when we sleep. I have no doubt that they exercise a

watching care over us, and often warn us of coming evil. Since my sister

Jane died, I never dreamt of this but once. What people think often about,

they commonly dream of. On that occasion, my sister, I thought, came to me,

clothed from bead to foot with roses ! I smiled when I saw her, with

pleasure, and awoke with the reflection that my sister, knowing my taste for

flowers, had chosen that way of expressing her happiness. ... You may smile

at this, and set it down as Robert’s silly superstition; but of one thing

you may be assured, that unseen beings care for you, and that nothing can

happen to you without the permission of our heavenly Father.”

|