|

While Robert Dick was

searching for organic remains among the rocks at Thurso during his leisure

hours, another scientific labourer was occupied in the same manner at the

opposite end of the island, among the rocks of Cornwall. Robert Dick had

discovered numerous remains of fossil fishes in Caithness, where

distinguished geologists had stated that no fossil fishes were to be found ;

and Charles William Peach had discovered fossil fishes in Cornwall, though

it had also been stated that the rocks there were non-fossiliferous. While

the one was disturbing the echoes of Pudding-gyoe, the other was hammering

in Ready-Money Cove. The two were working simultaneously amongst rocks of

the same epoch, and the results of their labours were in a remarkable degree

alike.

The Cornish worker in science was- then but a private in the mounted

coastguard service. Like Dick, in his hours of leisure he found time to add

materially to the facts upon which geology is based. Thus, at the same time,

Hugh Miller, originally a stonemason,—Robert Dick, a working baker,—and

Charles William Peach, a private in the coastguard service,—were all engaged

in like pursuits. “It is one of tlie circumstances of peculiar interest,”

said Hugh Miller, “with which geology in its present state is invested, that

there is no man of energy and observation, who may not rationally indulge in

the hope of extending its limits, by adding to its facts.”

While engaged in their respective pursuits, Dick

and Peach were quite unknown to each other. They worked on quietly and

unostentatiously, without any thought of fame. It might be said that theirs

was “the pursuit of knowledge under difficulties.” But this is a mistake.

The pursuit of knowledge is always accompanied with pleasure, and the

pleasure is only enhanced by the difficulties with which it is surmounted.

But circumstances shortly occurred which led to Mr. Peach’s promotion in the

service, and to his removal to the north—first to Peterhead and afterwards

to Wick. Then it was that Dick and Peach became the most intimate of

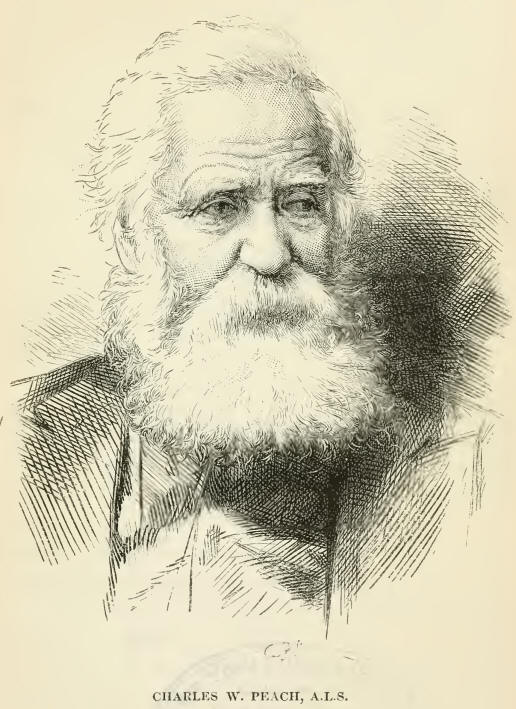

friends. For this reason it is perhaps appropriate to couple the portrait of

the one friend with that of the other,—not only because their pursuits

during their leisure moments were in a great measure the same ; but because

it serves as an introduction to the correspondence which follows.

Mr. Peach has told us the story of his life. We think it full of interest.

It shows what a man in even the humblest ranks of life may do, to accumulate

knowledge and to advance science for the benefit of his fellow-creatures.

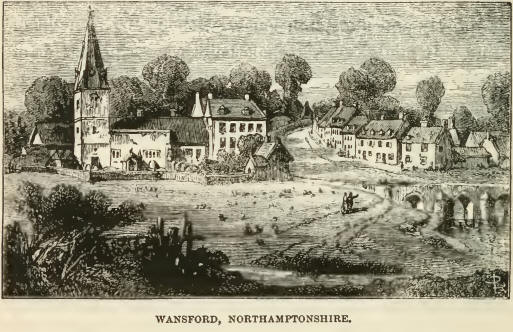

Mr. Peach was born in September 1800, at the village of Wansford in

Northamptonshire. At the time of his birth, his father was a saddler and

harness-maker, but he afterwards gave up the business and took a small inn

in the village, and also farmed about eighty acres of land. The time came

when young Peach had to be sent to school. He first went to a dame’s school,

where he speedily learned the ABC. After that he was sent to the village

school, the master of which had been an old sawyer. The man could no longer

saw, but it was thought he might teach. In those days any worn-out

brokenlegged man was thought good enough to be a schoolmaster. The old

sawyer knew very little about spelling. There was not a grammar-book about

the school.

But as old Mr. Peach was anxious to make his son a scholar, Charles was

taken from the old sawyer’s school at twelve years old, and sent to a school

at Folkingham, in Lincolnshire. There he made better progress. He learnt to

read and write well; and lie laid the foundations of the ordinary branches

of education. He remained at this place for three years, and at the age of

fifteen he left school altogether.

He returned to his father’s house to help in the work of the inn, and to

assist in the labours of the farm. It was not a very good training for a

lad. Peach was brought into contact with the people who frequented his

father’s inn. Wansford was then a very drunken village. Peach was often

invited to drink, but always refused,—a proof of moral courage at an early

age. He was consequently called “the milksop” of the house. Perhaps from

what he daily saw before him, he deter? mined to abstain from drink. In this

way the Spartans taught their children. At all events, though reared in an

inn, Peach abstained from liquor for the rest of his life.

Hot liking his position at home, Charles applied for the position of riding

officer in the Revenue Coastguard. He was appointed in January 1824, and

directed to proceed to Southrepps, in the county of Norfolk, and report

himself to the commanding officer there. After approval, he was directed to

take up his station at.Weybourn, in the port of Cley, Norfolk.

At that time Peach knew nothing of Natural Hist ory. He had never seen the

sea. What a sight, and how full of wonders, it was to him ! He was struck

with everything connected with it. He wandered along the shore, and found

brilliant seaweeds and zoophytes innumerable, the names of which he did not

yet know. He was particularly impressed by a splendid specimen, which was

placed on the parlour chimney-piece of the little inn where he stayed at.1

The appearance of the zoophyte strongly excited his curiosity. He determined

to know what it was, and where he could find a specimen for himself. This

little object had the effect of turning his attention to the study of

Nature.

He began to make a collection. He had no book on the subject. He collected,

more for the beauty of the forms and the colours of the agates. He would

know more by and by. Men in the Coastguard service were in those days turned

rapidly about from place to place, for no particular reason, but generally

at considerable expense to themselves. After being at Weybourn for a year,

Peach was removed to Sherringham, also in Norfolk.

It was while at this station that he met the Rev. J. Layton, then living at

Catfield. The reverend gentleman, finding that Peach was an enthusiastic

collector of zoophytes, asked him if he should not like to know the names of

the objects he collected. “Certainly,” was the reply. The clergyman then

invited him to his house, and showed him a book containing the history of

British zoophytes. He was delighted with the book ; but, as it was

expensive, and he could not purchase it, he went boldly to work, and copied

out the greater part of the letterpress. Although he had never had a lesson

in drawing, he also endeavoured, to the best of his power, to copy out all

the engravings. By this and other means, he laid the foundations of a great

deal of knowledge of the lower forms of marine life, while carrying on his

humble office of mounted guard in the Bevenue service along the northern

coast of Norfolk.

His business was to look after smugglers, and prevent them landing their

illicit goods at any part of the coast. His work was done partly at night

and partly by day. He must be constantly on the alert. The mounted guard

were not allowed to remain long in one place. After remaining at Sherringham

for about two years, Peach was removed to Hasboro. After a year’s service

there, he was sent to Cromer; then from Cromer back to Cley, where he

remained for two years. Here he married, and entered upon a new career, that

of bringing up a family on small wages. But he met every difficulty

cheerfully. He was fond of home life, and his wife helped to make his home

happy.

At Cley he was placed in charge of the station. He superintended the

look-out after smugglers, and he did his duty carefully. Notwithstanding

this, he was once charged with having neglected it. A jack-in-office, an

Irish naval captain in command of the coast service there, assembled the

Coastguard before him, and charged them all with being bribed by the

smugglers. Peach was justly indignant. He protested for himself and on the

part of his men that they were loyal and honest servants of her Majesty, and

he challenged the captain to prove his words. The captain could not; and

accordingly, after a little hard swearing, he drew in his horns, and said no

more on the subject.

It may here be mentioned that Mr. Peach was a handy man at everything. He

learnt to draw with correctness. He cultivated mechanics. When he went into

the Coastguard, he spent part of his spare time in making a turning-lathe.

With this he turned jet earrings, jet boxes, and other things. He afterwards

made a compound slide-rest, and turned things in iron and brass.

After two years’ service at Cley, Peach was sent to Lyme Regis in Dorset, at

the south-western part of the island. He then lived at Charmouth, hut he

remained there only four or five months, when he was removed to Beer, at the

mouth of the Axe, in Devonshire. He remained there for about two years,

always working in his leisure hours at zoology and natural history.

He was then removed to Paignton in Tor Bay, farther down the coast. He was

not allowed to rest there, but was shortly after removed to Gorranhaven,

near Mevagissey, in Cornwall. It was here that he indefati-gably pursued his

studies in zoology. He collected some of the most delicate specimens of

marine fauna. Many of these he sent to Dr. Johnston when preparing his

history of the British Zoophytes. Others were sent to the most distinguished

writers on zoology, and several of them were called after his name.

It was while living at Gorranhaven that Peach applied himself to a new

subject,—the geological formation of the coast. It had been stated by

well-known geologists that no relics of ancient life existed in the Cornish

rocks. “We have no exuviae,” said Pryce, “of land or sea animals buried in

our strata.” "The rocks of Cornwall and of Scotland are non-fossiliferous,”

said Dean Conybeare. The same statement was repeated by many writers, and

amongst others by Sir Roderick Murchison, who took the statement on trust.

In fact, geology was then in its infancy. During the last fifty years,

nearly everything has been changed.

The private in the mounted Coastguard service did a great deal to alter the

then state of geology. He was not satisfied with the statements of others.

He examined for himself. He had the quick eye and the keen judgment. He

possessed the gift of careful observation. Nor was he ever daunted by

difficulties. In fair weather and in foul, he worked among the Cornish

rocks, and found fossils where no fossils were said to have been— fossils

innumerable!

Mr. Peach was not the man to let his light lie

hid under a bushel. A meeting of the British Association was about to be

held at Plymouth. Plymouth was not far from the place where he lived, and he

determined to put his facts together, and read them before the association.

He never wrote a paper before, nor had he ever read one. He had only heard

one scientific lecture. But with his ready mother wit he prepared his paper,

and it proved to be a thoroughly original one. He read if himself at the

Plymouth meeting in 1841. It was entitled, On the Organic Fossils of

Comical?.

“It is impossible,” he writes in 1847, “to describe the feelings under which

I then rose. That is over long since. The only beating of my heart now about

the British Association is, that of gratitude towards its members, and of

affection for their great kindness. I feel my love of scientific pursuits

strengthen every day. I have taken hold of that which every day affords f a

feast of reason and a flow of soul/”

In the following year (1842) he attended the meeting of the British

Association at Manchester, where he read a paper before the Zoological

section on his discoveries and observations of the marine fauna on the

Cornish coast. In 1843 he attended the meeting at Cork, and in 1844 he was

at York. He never went without a paper. Sometimes he read several. Men of

distinction began to notice this remarkable coastguardsman. He was

acknowledged to be one of the most original discoverers in geology and

zoology. Such men as Murchison, De la Beche, Buckland, Forbes, Daubeny, and

Agassiz, took him by the hand and greeted him as a fellow labourer in the

work of human improvement and scientific development.

Dr. Robert Chambers was present at the York meeting. He wrote a very

interesting article on the subject, which appeared in Chambers's Journal of

November 23, 1844. Here is his description of Mr. Peach:— “But who is that

little intelligent-looking man in a faded naval uniform, who is so

invariably seen in a particular central seat in this section? That is

perhaps one of the most interesting men who attend the association. He is

only a private in the mounted guard (preventive service) at an obscure part

of the Cornish coast, with four shillings a day, and a wife and seven

children, most of whose education he has himself to conduct. He never tastes

the luxuries which are so common in the middle ranks of life, and even

amongst a large portion of the working classes. He has to mend with his own

hands every sort of thing that can wear or break in his house. Yet Charles

Peach is a votary of natural history—not a student of the science in hooks,

for he cannot afford hooks; hut he is a diligent investigator by sea and

shore, a collector of zoophytes and echinodermata—strange creatures, many of

which are as yet hardly known to man. These he collects, preserves, and

describes; and every year he comes up to the British Association with a few

novelties of this kind, accompanied by illustrative papers and drawings

thus, under circumstances the very opposite of such men as Lord Enniskillen,

adding, in like manner, to the general stock of knowledge.

“On the present occasion he is unusually elated, for he has made the

discovery of a holothuria with twenty tentacula, a species of the

echinodermata, which Edward Forbes, in his hook on Starfishes, had said was

never yet observed in the British seas. It may be of small moment to you,

who perhaps know nothing of holo-thurias, hut it is a considerable thing to

the fauna of Britain3 and a vast matter to a poor private of the

Cornwall Mounted Guard. And accordingly lie will go home in a few days, full

of the glory of his exhibition, and strung anew by the kind notice taken of

him by the masters of science, to proceed in similar inquiries, difficult as

it may be to prosecute them under such a complication of duties,

professional and domestic.

“But he has still another subject of congratulation; for Dr. Carpenter has

kindly given him a microscope4 -wherewith to observe the structure of his

favourite animals,—an instrument for which he has sighed for many years in

vain. Honest Peach! humble as is thy name and simple thy learning, thou art

an honour even to this assemblage of nobles and doctors; nay more, when I

consider everything, thou art an honour to human nature itself; for where is

the heroism like that of virtuous, intelligent, independent poverty ? and

such heroism is thine!”

Some of the gentlemen who attended the meeting at York, and especially Dr.

Buckland, in their admiration for the character of Mr. Teach, proposed to do

something for his promotion in her Majesty’s service. Dr. Buckland wrote to

Sir Eobert Peel on the subject. The reply was, that there were no openings

at the time, but that the application of Dr. Buckland on behalf of Mr. Peach

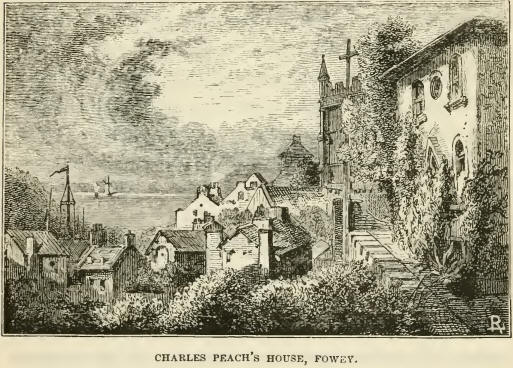

should be kept in mind. At length the promotion came. A position of Landing

Waiter was vacant at London, and another at Fowey. Mr. Peach prelerred the

latter, though the salary was £50 less. He desired to remain in his quarters

by the sea-coast, to carry on his investigations among the zoophytes, and to

further examine the rocks of Cornwall at his leisure. His salary was now

£100 a year; and the advance of pay greatly helped him and hiğ lamily. He

removed to a pretty house overlooking the river Fowey and the English

Channel, and at this house Mr. Tennyson, the Poet Laureate, was a frequent

visitor.

While residing at Fowey, Mr. Peach became an honorary member of all the

scientific societies in Cornwall. But he was far more than an honorary

member. He greatly enriched their collections. He added many organic remains

of the Devonian Bocks to the admirable collection of the Boyal Geological

Society of Cornwall. Indeed, the collection seems to have remained as Mr.

Peach left it, some thirty years ago. The President of the Society, at the

meeting in 1877, thus referred to the museum at Penzance:—“Our collection

contains Devonian forms from the lower, middle, and upper series, in most of

those areas in the counties of Cornwall and Devon, where the rocks are

exposed. It must be allowed that it is essential to the credit and future

history of the Society that this, of all groups of rocks and associated

fossils, should be well, if not perfectly, represented in the museum. The

collection, as it now stands, is in the main due to the energy and industry

of Mr. Charles Peach, A.L.S., one of our oldest living naturalists, who for

many years resided on the south coast of Cornwall, there making a special

study of the coast sections, and who extensively collected from them,

especially at East and West Looe, Polperro, Polruan, and Fowey. This truly

great collection is now displayed in the cases of our Society, and has been

but little added to since,—a circumstance especially to he regretted, when

we take into consideration the great amount of work and research that has

been done and carried on in foreign countries.”

As constant movement from place to place seems

tc be the rule of the Ee venue Service, Mr. Peach left Fowey in 1849; and

this time he was sent to a far-distant place—to Peterhead, in the north-east

of Scotland. The removal cost him a great deal of money. His own expenses

were paid, but he had to remove his wife and family at his own expense. Yet

it was a promotion in the service. He was now Comptroller of Customs. The

dignity of the appellation was much greater than the advance of salary,

which was only £20 a year. Still it was a promotion, and it might lead to

better fortune.

At Peterhead, as in Norfolk, Devonshire, and Cornwall, Mr. Peach went on

with his study of zoology and geology. He added to the list of British

fishes, Yarrell’s Blenny, Pay’s Bream, and the Anchovy,— which had not

before been known to inhabit the seas which wash the north-eastern coast of

Scotland. He also devoted much attention to the nest-building habits of

certain sea shells and fishes. “At Peterhead,” says Professor Geikie, “he

made himself intimately acquainted with the family arrangements of that

rather fierce-looking little fish, the fifteen-spined stickle-back (Gaster-osteus

spinachia). In a rocky pool he discovered a colony of them, and learnt how

they built their nests and deposited their ova. He watched the hatching and

growth of the young until the whole colony, young and old, took to the sea.

As he used to visit them five or six times a day, the parents grew so

familiar that they would swim round and touch his hand, though on the

appearance of a stranger they would angrily dash at any stick or incautious

finger that was brought near them. The same habit of close and cultivated

observation was shown by his study of the maternal instincts of the female

lobster in its native haunts.”

Mr. Peach’s next removal was to Wick,—the greatest fishing town in the

North. Though an ardent lover of nature, he never neglected his duty. He was

as accurate and quick-sighted in business as in science. He was alike

shrewd, wise, and observant in both. He was the model of a Comptroller of

Customs, as he was of a true collector and naturalist. His removal to Wick

was a promotion. His salary was advanced to £150 a year, though his duties

were to a certain extent enlarged. Part of his work consisted in travelling

round the coast of Caithness in search of wrecks, and reporting them to the

Board of Trade. This led him to travel to the rocky points of the coast,

where the wrecks principally occurred; and he made good use of his spare

time by hammering the rocks in search of fossils, and more particularly the

fossil plants with which the dark flagstones of the district abounded.

His removal to Wick occurred in 1853. One of the first things that he did

was to travel across the county to pay a visit to Eobert Dick at Thurso.

While he resided in Cornwall, the name of Eobert Dick had been a household

word with him. He knew what he had done from Hugh Miller’s writings, and he

had no doubt that he would find Dick to be a man after his own heart. for

was he disappointed. When he first called at Dick’s shop in Wilson’s Lane,

on the 19th October 1853, he found that the “maister,” as his servant called

him, was in the bakehouse. The caller sent in his name, and the baker

speedily appeared in the front shop, his shirt sleeves rolled up, and his

arms covered with flour.

“I’m Charles Peach of Eeady Money Cove in Cornwall ; and you are Eobert Dick

of Pudding Goe.” That was Mr. Peach’s first introduction. “How are ye?”

answered Eobert Dick, with a firm grasp of the hand; “come into the

bakehouse!” That was an honour accorded to few, but in the case of a

renowned geologist it was readily granted. Dick went on with his work at the

oven mouth, or at the side of the dough, while the two talked together. It

was an interesting conversation, which Mr. Peach long remembered. The latter

observed on the wall of the bakehouse a full-sized sketch of the Greek boy

taking the thorn from his foot, with an Egyptian god on each side,—all

accurately done in pencil or charcoal by the Thurso baker.

Mr. Peach called again in the evening, and again t’ound Dick at the oven in

the bakehouse. After he had done his evening’s work, lie had a fire lighted

in his parlour, and took his new friend upstairs to see his collection. Mr.

Peach was first attracted by the fine busts of Sir Walter Scott and Lord

Byron, and a large plaster figure of the Yenus of Milo, which the apartment

contained. Dick then showed his collection of fossils, plants, ferns, and

entomological specimens. Mr. Peach, in an entry in his diary, written the

same evening, says—“ He is a very diffident man, but an enthusiast in

natural history pursuits. He is unmarried, and lives most retired. In fact,

he is very little known in Thurso. He has a nice collection of Caithness

ferns, beetles, and insects. He is deeply interested in botany. His

researches in geology have been great, especially in the Old Bed Sandstone;

and some of his specimens have added new links to the history of these

ancient rocks.”

Mr. Peach soon repeated his visit. He called again at the beginning of the

following May, and again found Dick very busy in his bakehouse. The fire was

not again lighted in the parlour. Peach was now regarded as a friend. All

the subsequent interviews between the two occurred at the mouth of the oven,

or in the kitchen, or in the fields, or among the rocks. All ceremony and

formality were laid aside; and although they had many differences of opinion

and stout debates, these were, like lovers’ quarrels, soon made up.

Mr. Peach entered the following passage in his diary, descriptive of his

second visit to Dick :—“2d May 1854. Bose early; called upon Mr. Dick; found

him at his oven, and very busy; had a nice chat with him. ... In the evening

I saw him in his bedroom. What an industrious man he is. He is through

nineteen volumes of plants, and hopes soon to finish his herbarium. He has

heaps upon heaps of specimens, and appears to thoroughly understand Ills

subject. After two hours’ chat I left him to go to his bed, to which, if

possible, he retires at 9 p.m., to rise again between 3 and 4 a.m. I have

often been up and with him at that time, not willing to lose time when I had

an opportunity of enjoying his society. His conversation was too precious to

lose.” During the ensuing summer, when the grasses and plants were in bloom,

the two took a long walk up the Thurso river. Dick pointed out to his friend

the habitat of the Holy Grass (Hierochloe borealis), which he had long

known; and also what was then called Drummond’s Horsetail (Kquisetumpratense).

Dick also pointed out the Baltic rush (Juncus balticus), which Mr. Peach had

never before seen. Mr. Peach says of this walk, that “Dick’s cheerful

manner, his sparkling wit, and frolicsome playfulness, added to the other

beauties of the excursion, made it a treat indeed.”

“My next visit to Thurso,” says Mr. Peach, “occurred in connection with a

wreck, happily unattended with loss of life. On this occasion, our first

difference broke out. The Old Bed Sandstone period was said to be one of

seaweeds and cartilaginous fish. That I felt to be unstable, from specimens

which I had picked up in my spare minutes snatched from duty. We both

defended our views. He was strenuous in his defence of Hugh Miller’s and his

own opinions, and although I felt a sad heretic, I warmly, but I hope

modestly, suggested that I might be right. Time has since proved that I was

so, and dear Dick set to working out the problem for himself as usual, and

at last lie came to the same conclusion that 1 had done. I have just found a

note in reply to one of mine. After saying that he is ready to be my pupil

in seaweeds, zoophytes, and in every other department of natural history, he

adds, and ‘even in fossil wood’—a jocular allusion to our discussion on this

point.”

Mr. Peach, in a recent letter, referring to the many happy hours and tough

battles fought in Dick’s bakehouse, says that old Annie, the housekeeper,

would sometimes interfere, and say, “ Eh, maister, ye’re awfu’ hard wi’ Mr.

Peach; he’ll never come back again after sic rough usage.” But Peach came

back as before. The lovers’ quarrels soon healed, and they were more

affectionate than ever. “ I had the advantage,” says Mr. Peach, “ in having

read all that Hugh Miller had done, and also many of Dick’s letters on the

same subject. Besides, I had had lots of experience in Devonian and Old Bed

rocks in more places than Scotland. I had also a mode of my own for

collecting. I got all the weathered and detached portions of fishes and

plants, studied them, and fitted them into more perfect specimens. But Dick

did much good service. He was fortunately in time to reap the harvest. I

only got his gleanings. But I found for myself new fields of unworked rocks

in Suther-landshire, and got new fishes there, and also new ones in the old

fields that Dick had so long been working in.

I was very fortunate. My duties led me so far about, and gave me many

opportunities that I should not otherwise have had ; whereas Dick was

confined to the neighbourhood of his bakehouse in Thurso. All this I took

advantage of, after duty had been done. By rising early in the morning and

working until late at night; by often giving up my meal times, and

satisfying myself with a crust of bread and butter, and at night with a

Highland tea and something to eat, I fortunately contrived to fill up my

leisure hours with a good deal of useful work.” The principal new field to

which Mr. Peach refers, was the limestone of Durness in Sutherland. The spot

was too far from Caithness to enable Dick to investigate it. But it was in

the Comptroller’s way. He went to Durness to visit a wrecked ship, and he

did not neglect liis opportunity. He was the first to find fossils in the

limestones of Durness. Obscure organic remains had before been detected by

Macculloch in the quartz rocks of Sutherland; but they had gradually passed

out of mind, and their organic nature was stoutly denied even by such

geologists as Sedgwick and Murchison. Mr. Peach, however, brought to light,

in 1854, a good series of shells and corals, which demonstrated the

limestones containing them to lie on the same geological horizon as some

part of the great Lower Silurian formations of other regions.

The discovery remained without solution for some years, the principal

geologists still doubting its reality. But about five years after, Sir

Roderick Murchison again visited the spot, and the discovery was confirmed.

Professor Judd, of the Royal School of Mines, Jermyn Street, London, said in

the Geological Society's Quarterly Journal that “Charles Peach’s discovery

in 1854 of Silurian fossils at Durness, Sutherland, has already borne the

most important fruit; and, in the hands of Murchison, Ramsay, Geikie,

Harkness, and Jamieson, has afforded the necessary clue for determining the

age of the great primary masses of the Highlands of Scotland.”

We have thus described the origin of the friendship between Charles Peach

and Robert Dick. It strengthened as it grew. Charles Peach shared all Dick’s

enthusiasm, and bore a warm and constant friendship for the solitary

student. They communicated to each other, as all true labourers in science

do, the results of their respective discoveries. They kept up a regular

correspondence, and many of their communications with each other will be

found referred to in the following pages. |