|

Hugh Miller corresponded

regularly with Robert Dick during the preparation of his later works on

geology. He sent him the proof sheets of his forthcoming books for the

purpose of having Dick’s corrections. Even as regards the Old Bed

Sandstone—Miller’s first geological work—Dick furnished him with many

additions and corrections. For instance, he sent him the first specimen of

the gigantic Holoptychius found under the lower beds of the Old Red

Sandstone, which enabled Hugh Miller to correct the theory set forth in the

two previous editions of his book. Dick also enabled Hugh Miller to

determine positively that Dipterus and Polyphractus were one and the same

fish.f Dick also furnished his friend with numerous specimens of the

Diplopterus, Osteolepis, and Asterolepis, accompanied by drawings of these

fossil fishes. When sending them, Dick said, “I am far from attaching any

value to these drawings. To me labour is its own reward. You can cut and

carve out of them as you please.”

Hugh Miller’s Footprints of the Creator was published in 1849, and here also

we find numerous indications of the assistance which he had received from

Eobert Dick. Professor Agassiz, in his preface to the last edition of the

book, says, “Many points respecting this curious fossil (the Asterolepis or

Star-scale) remained to be determined; and it was fortunate for science that

Mr. Miller was enabled to accomplish this object by means of a variety of

excellent specimens which he had received from Robert Dick.” “The remains of

an Asterolepis found by Mr. Dick at Thurso indicate a length of from twelve

feet five to thirteen feet eight inches. ... A specimen of Asterolepis

discovered by Mr. Dick among the Thurso rocks, and sent to Mr. Miller,

exhibited the singular phenomenon of a quantity of thick tar lying beneath

it, which stuck to the fingers when lifting the pieces of rock. What had

been once the nerves, muscles, and blood of this ancient ganoid, still lay

under its bones. The animal juices of the fish had preserved its remains by

the pervading bitumen, greatly more conservative in its effects than the oil

and gum of an Egyptian undertaker.”

The first cranium of the Asterolepis figured by Hugh Miller was imperfect.

Robert Dick furnished him with a perfect one. There was a gap in the print

which struck Professor Sedgwick as being unnatural. He said it was “not of

the proper finish.” But after Dick had furnished his specimen with the

keystone-shaped plate in its proper place, Miller says he referred the

professor to the geologist at Thurso “ as the true authority for determining

how nature had given the last finish to the cranial buckler of the

Asterolepis. ‘ Ay/ he exclaimed, as he eagerly knelt down to examine the

specimen, and passed his fingers over the keystone-like plate,—‘Ay, this is

a finish of the right kind! This will do!’”3 Dick also furnished Mr. Miller

with a well-defined jaw of the Asterolepis, and with a drawing of a section

of its tooth, which appeared among the illustrations of the book.

Dick found for Mr. Miller—apropos of a conversation which the latter had

with Professor Owen—a specimen of the Diplopterus, which fully confirmed the

professor’s views as to the prolongation of the brain of that fish. In fact,

there was scarcely a subject on which Hugh Miller wanted further

information, but Eobert Dick was ready to supply it. It was a delight to him

to labour night and day for the benefit of his friend, and also for the

benefit of science. In one of his letters to Hugh Miller he says—“Your

letter found me asleep, knee-deep in fern howes. But now I am awake, and

busy night and day.”

Hugh Miller, on his part, was ready to acknowledge the obligations which he

owed to his friend. At a lecture delivered by him before the Physical

Society of Edinburgh “On a Suite of Fossils, illustrative of the relations

of the Earlier Ganoids,” he said, “There are several rare and a few unique

fossils on the latter, illustrative of various points in the structure of

the first ganoids, to which I can only refer the members of the Society as

worthy of their examination. They are in part the fruits of a leisure

fortnight spent this autumn among the rocks of Thurso; but in still greater

part I owe them to the kindness of my indefatigable friend Mr. Robert Dick,

of whom I may well say that he has robbed himself to do me servicer

The same lecture is full of the obligations which he owed to Robert Dick. He

pointed to the Homocanthus arcuatus, which, though found in Russia, had only

recently been discovered in Scotland by his friend. To him also he owed the

Hoplacanthus marginalis, another Russian placoid of the Old Red. There was

also a magnificent specimen of the Asterolepis, which had enabled him to

determine the place and form of a thickly-tubercled, well-marked place on

the middle of the palate. This also had been sent to him by Robert Dick.

In sending this fine specimen to Hugh Miller, Dick says—“I give it you most

cheerfully. Your kindness deserves it. To any other I would not have parted

with it.” At the same time he sends him the jaw of a fossil fish, showing

the outer row of teeth. “Looking at them with the glass,” he says, “they

show a very beautiful star-like arrangement of the channel through which

nourishment flowed to the tooth.”

Dick continued to correspond regularly with Hugh Miller. He spoke to him

very freely. He thought that he was sometimes twisting geological facts to

suit a religious theory. Dick thought very little of “authorities,” but he

greatly valued facts—tested and re-tested. “It is not,” he said, “by driving

along the public roads; strolling along the sea-shore; taking a distant view

of Morven through a spy-glass, that the depth of the Caithness schists is to

be ascertained. No! The very fact that the schists dip in almost every

direction might have led ‘ authorities ’ to suspect that the granite was not

confined to primary hills; but, like the stately oak, sent out its branching

roots far and wide. You, Mr. Miller, rule solely by 5 authorities/ Your

humble servant has often found them sleeping, and has no reverence for

them.”

Indeed, Dick had no hesitation in correcting the very highest authorities.

“Nothing,” he said to Miller (26th September 1850), “is more at fault than

the idea sought to be established by Sir Eoderick Murchison’s section in the

front of your volume on the Old Eed Sandstone, that the general dip of

Caithness rocks is all in one direction. No such thing! I candidly tell you

that *my masters* must revise their views before I can feel the smallest

respect for what they say about Caithness. I cannot resist the evidence of

my senses. Take, for instance, the Hill of Buckies, which you saw.- The dip

there is north-east, whereas at Thurso the dip is north-west.

“Of course, I am very far from wishing you to meddle with the findings of

men driving along the public road and viewing the country from gigs! No! But

it is my misfortune to laugh outrageously during my rambles to find the

Caithness rocks dipping in every airt of the compass, whereas it is stated

in geological books that they dip in only one direction!”

Robert Dick was not afraid of correcting Hugh Miller himself. In one of his

letters he says:—“You have fallen, into error in your Old Bed Sandstone. You

have described Caithness as a vast pyramid rising perpendicularly from the

bases furnished by the primary rocks of Sutherland, and presenting newer

beds and strata as we ascend, until we reach the apex.

“Now, Mr. Miller, this is not only incorrect but calculated to deceive. But

yon are not to blame. It is the getters-up of the geological maps who are to

blame. You work by the geological maps. Geological maps and treatises are

got up by men in red-hot haste, on data proved to be erroneous years ago.

New books, with nothing new in them but the paper and ink! The public are

gulled, and the poor student, panting for knowledge, fills his belly with

husks, and by and by he regards his new books with derision !

“I am working very hard—sometimes seeking new fossils but finding none;

sometimes rambling far over the hills and finding a junction of the Old Red

very different indeed from the respectable ‘authorities’ in Edinburgh. As

for the maps, I have handed them oveT to the devil as the most detestable

pieces of imposture ever obtruded on a discerning public. ‘Discerning’

indeed!

“Your Edinburgh Professors can put on their spectacles next time they travel

north. If they wish to be respected, they must be a little more particular.”

Dick himself had bought one of the best maps of the time. He used it for

travelling purposes. He noted down on it the direction of his journeys. He

marked the dips of the strata in nearly every part of the county. He noted

the disturbances, the faults, the beds in confusion, the sites of the

boulder clay, the flagstones, the red sandstone, the gneiss, the

conglomerates, and the various geological formations of Caithness. The map

is full of his marks. In some places, where a river or a loch is put, he

marks “nonsense” or “stuff,” meaning that there is no such thing. This map

must have been his pocket-companion for many years. Underneath it he writes

:—“I have been rambling over Caithness since 1830, and anything more unlike

the truth than the above picture I have never seen. There is no pleasure in

marking anything on it. I have made an attempt to put in roads. The dip is

often seen by the road-sides.” Writing to Hugh Miller about the geological

maps of Caithness, he said:—“It would be easy to construct such a plaything

as those maps of Messrs. -, and -, but when you had done so, would the toy

meet the felt necessity ? . . . 0 brave gentlemen! bold men and daring! how

gallantly you have set the truth aside! —here laying down your fancy ovals,

there your halfmoon patches! just as if Nature were strictly bound down to

mathematical figures, squares, and circles. How inimitably you have run your

Old Red in Caithness sheer up to the root of Morven, in defiance of every

intervening obstacle. Outbursts of granite are nothing. No ! Their

iron-pointed crests (stubborn facts) standing up here and there are only

trifles, yet they riddle in rotten holes your pretty pictures! . . . For on

such things men now-a-days found their Deep Philosophy.

“Seriously, if any junction of Old Red with the granitic rocks be as

irregular and complicated as that in Caithness, it will be no easy task to

delineate it correctly ; and unless it be correctly done it will be of no

value. It would require such an amount of time and patience, such a crossing

and re-crossing of the county, as few private individuals could venture on.

“For my own part, though I grumble at toil as little as any man, I have, so

far as regards any serious intention of doing such a thing, given it up. At

the same time, as I ramble now and then, I will have an eye to it, and that

is all. Let the Government do it; they only can order it to be done

properly.”

Then, about the new-fashioned ideas about geology he said:—“Since the

fashions,’ to use your own words, ‘have not passed away,’ how provokingly

strange will you deem it, if you and the rest of your scientific brethren

settle down at last to the conviction that this earth never saw a creation

but one. . . . Though difficulties and doubts innumerable stand in the way,

they may yet be brushed aside like morning mists, and the simple truth shine

forth clear and luminous as the sun.

. . . See ! says some observer, the dreams of our wise men! They tell us

that the dead animals entombed in the solid rocks do not belong to one

creation! and behold, they still exist. The animal whose shell they name

Nummulite still lives in the Mediterranean. The Pentacrinite lives in the

West Indian seas and in the bay of Dublin. . . . Your 'Theory of Degradation

’ is at least a very ingenious piece of pleading; hut if I am right in

supposing that it rests mainly on the idea that no reptiles existed during

the period that the lowest fossiliferous strata were accumulating, then I

say you may yourself live to re-write that part of your story, [n the

progress of discovery, the whole series of geologic speculations may change.

From the very nature of the investigations, an element of uncertainty must

for a long time mingle in all your most valued performances. That stern,

startling fact of ferns in the Orkney schists must in no small degree tend

to unsettle all fixed belief in the findings of the stone philosophers, if,

indeed, any belief can really belong to them.”

At Miller’s request, Dick again went out to do his biddings. “Referring

you,” he said (24th December, 1849), to a promise I made to you when down at

Thurso, to examine the groovings and polishings, by removing a little of the

soil in the locality in which you detected those marks, I wish to remark

that the work is done. You might think me dilatory and slothful, but I could

not accomplish it sooner. In the first place, the business was retarded by a

severe frost. Winter held his iron rule ; and could you have seen the place

over which you rambled in July last, you would have beheld a strange

metamorphosis. The strata were wholly covered wit]/ sheets of ice, with long

fantastic icicles hanging from every precipice. The air was still, and the

sea without a ripple. Of course nothing could be done; it was too icy, too

cold.

“The scene changed to another phase, not a whit more endurable. A cold,

‘blae, eastlin’ wind, accompanied by driving sleety showers, whistled along

the watery turmoil. This was followed by a close, dense, foggy drizzle. Bogs

and mires were impassable to ordinary folk. Patience said ‘ Wait'

“Well, I waited. Winds and rains are but a tide. The eastern sky at length

frowned, and stormed, and wept itself into sheer good humour. The air became

dry and mild, and a delightful morning at length dawned. I took up my spade

and went off to the spot, in order to solve your query.”

“I remember that I was much struck by the phenomenon, when you pointed it

out to me on the top of yon dizzy precipice. I was no less astonished on

seeing it a second time. To me these wonders are never old. Their edge never

dulls. They always stir me.

“I laid bare the rock for about two feet. I did not feel entitled to do any

more. I felt I had no right to strip the soil off any man’s property, so I

desisted. But it was quite enough. The rock, beneath the soil, was polished

and grooved, in even a more beautiful manner than when you saw it. The

bearings of the groovings and scratches were, as near as could be determined

without a compass, west and east.

“On coming homewards, I noted, at a spot where Lady Sinclair had caused a

small runnel of water to be diverted in order to form a mimic cascade, a

good piece of the rock laid bare of the soil; and the surface of that rock

was grooved and polished similar to the other.”

This unmitigated hard work injured Dick’s health. He did not sustain himself

properly. On his long journeys of forty or fifty miles he had only a little

biscuit to eat. He drank from the nearest spring. There were not only no

public-houses along the districts which he travelled through; but no houses

of any kind. There were only moors, and mosses, and mires.

On the 28th of January 1850, he sent Hugh Miller the head plate of an

Asterolepis. He found the heavy stone in which it lay concealed, five long

miles from Thurso. He hammered and chiselled, and took out the stone

himself; but he could not carry it away. He hid it until he could get some

help. He hired a man, and the two went out in the dark with a wheelbarrow to

bring it home. It was a very heavy stone. They carried it “ up the brae at

the shore,” and placed it carefully in the wheelbarrow. The two trundled it

home, turn and turn about, until they reached Dick’s house in Wilson Lane,

late at night. In a future letter to Hugh Miller he says :—“Truly the labour

of digging it out has nearly finished me. I worked too hard, caught cold

afterwards, and I am no better yet.”

On Miller’s asking him to go out and further observe the groovings on the

hill-sides, he says :—“The thing shall be attended to. But, Mr. Miller, I

have not been to the hills this winter, not since October. Not that I am

forgetful or unmindful of such affairs. But many conflicting cares will be

creeping in and annoying one. Thus the course of stone love cannot run

smooth. For three weeks and more I have been grinding the few stones I have

into something of a neater shape, rendering them less cumbrous and more trim

and smooth. Truth to say, it is hard work, and requires enthusiasm.

Geologists should be all gentlemen, with nothing else to do.”

The means by which Dick sawed and polished his stones, were very simple. An

old cask about the size of a herring barrel set on its end, and supporting a

board or flat stone, was his bench. He had a short portion ol the common

hand-saw, fitted by himself with a rough wooden handle. With this, and the

addition of a little sand and water, he trimmed the stones containing the

fossils, and afterwards polished them by rubbing the two surfaces together.

This work is generally done by machinery; but Dick did it all by the

strength of his arms. It occupied a great deal of time, and was often very

heavy labour.

Hugh Miller plied Dick very hard. He was constantly writing to him, asking

for further information. Mr. Miller was then contemplating his new book—The

Testimony of the Rocks—for the purpose of reconciling geology with the

Mosaic account of creation. The matter of the book was first delivered as

lectures. “You ask me,” said Dick, “what good news I bring you from the

shore, from the quarries in the hills, and from the quarries in the plains

?” I answer, simply nc news at all.

“Since February last, I sauntered east, I sauntered west; in fact, I am

almost as familiar with every rocky ledge sixteen miles on every side of

this place as you are with the desk before you. I have peered into them all,

and still there is no news. Old Boniface ate his ale, drank his ale, and

slept upon his ale. So may I say, I have ate on the strata, I have hammered

the strata, and sometimes I have sat down and fallen asleep on the strata;

and, after all, I am not one whit the wiser.

“One sunny morning I found myself on the seashore at Barrogill. I had been

there before, but I was never so sure of achieving wonders as I was on this

occasion. The Pentland tides had receded to the lowest ebb, and the whole

range of stratified schists lay dry and inviting. I set gallantly to work,

and charged along one ledge and down another; up a third, and across a

fourth; retreating, advancing, wheeling, kneeling, poking, poring; now to

the right, now to the left; then the last tremendous assault, and all is

over, save ‘ Try again.’

“Well, I found a bed of very dark bituminous schist, very dark whilst wet by

the sea. It almost seemed of a coal colour, though the stone, when dry, is

brownish. In fact, the strata differ in nothing essential from similar

bituminous beds at Brims and near Thurso. In those strata I found nothing,

save detached scales of Diplopterus, droppings, detached spines of

Cheiracanthus, and bits of broken bones of Coccosteus. Here and there, in

those beds, lay roundish and irregularly shaped dark-coloured pellets, of

what looked like bituminous nodules.

... I turned away, and wound my way Dunnet-wards, examining every accessible

ridge on my way up. There is a wondrous similarity among the rocks of

Caithness everywhere, though from the Haven of Mey up to Scarskerry they are

charged with iron to a greater extent than in any other spot. At the little

Mill of Mey they are literally red as keel, and, tilted up at a high angle,

dipping north-east. ... As I passed an, looking down from the rocks, I could

identify the dark Barrogill bed, buried deep beneath those rough red strata.

And in some gyoes I exclaimed, as I looked down, ‘There’s Thurso beds! and

there, and there !’ “Near Scarskerry, at a jutting promontory, the dark

bituminous beds, and grey limy beds, many feet in thickness, are seen tilted

up at an acute angle, thin, slaty, rugged, and hard, and across their sharp

edge the chafing waves roll twice every day.6 I had marked them often as I

passed along at former visits; but the white surf had debarred me of the

pleasure of a reconnaisance. But this time ’twas all right, and I plied the

hammer where hammer had never been plied before. . . . I found a few broken

fragments of Asterolepis, scales of the same, and a few scales of

Diplopterus.

Hot another article did I find, although I tried until the incoming tide

threatened to cut off my retreat tc the land. And then I fled.

Dick went on with his ramblings, and sent, as usual, the results to Hugh

Miller. He went to Barrogill and Gills Bay on the Pentland Firth, marking

the dips of the flags and red sandstone. At the junction of Gills Burn with

the Firth he found several beds of bituminous shale, containing fossil

coprolites and large seaweed plants not unlike a stout bough. This was

afterwards engraved in Hugh Miller’s Testimony of the Bocks. Dick found the

beds of clay slate interlacing with the huge mass of red sandstone before

him, and up Gills Burn he saw a beautiful section of boulder clay. No less

than three little streams have cut their course through the boulder clay,

laying bare their internal structure most beautifully. In one of those

little streams you walk up into the very bowels of the earth, with a

perpendicular wall on each side of you, picking out at your leisure Crassena,

Mactra, Cyprina, Turritella, Dentalium, chalk, flints, pieces of Oolite, and

such like.

“Freswick Burn is nothing, Harpsdale is nothing, the Haven of Mey is nothing

to a geologist, compared with this. I wish you no higher gratification than

an hour spent among the clay and shells at Gills Bay. This section is

noticeable because it exhibits at the base, just where it rests on the red

sandstone, a bed of gravel and shells—broken and intermixed together— a

thing I never saw in connection with any other section. I have seen, here

and there, small gravel nests of various shapes, but never at the base line.

In truth, I do not remember ever seeing the base line of a section of

boulder clay until I saw this one”

From Gills Bay, Dick went westwards to the bay of Scotland Haven, where he

found various remains of the Asterolepis. He brought away a few of them,

more by way of memorial than because of their value. “The slates from this

locality on to Dunnet,” he says, “dip east-north-east, and in many places

they are in complete confusion. As I passed homewards, my thoughts reverted

to the ignorance of those who imagine that Caithness strata have in general

one particular dip—one general dip/ A greater delusion never entered the

brain-box of mortal man.”

Dick’s next ramble was to Bencheilt, about twenty-five miles south of Thurso.

His wish was to examine the granitic debris, and to correct the observations

made during his midnight journey to Dunbeath about three years before. He

went by Sordal and Spittle Hill, where the strata dipped east. At the

thirteenth milestone, he found the granitic debris, and it continued to

Stemster Hill. Passing a Druidical pillar, nine feet high, he went on to

Bencheilt. He was twenty miles from home. His time was nearly up ; yet he

determined bo ascend the mountain. Observing, however, that the Loch of

Stemster was close at hand, and that a Druid’s temple stood on its side, he

resolved to go over and see the great antiquarian monument.

“The Druidical temple,” he says, “is not a circle. It is shaped like a

liorse-shoe—like an old-fashioned reticule basket, or rather like an old

wife’s pocket— pardon the simile. The stones are from the hills around. The

highest stone may be six feet high; their average height about four feet.

They are grey, moss-grown, and lichened; and upon some of their points the

hammer of the antiquarian has hit very hard. At the north-east corner is a

small space, outside the circle, at the foot of a large stone—the second

stone in the end row,—at which some person has been digging for relics, and

has left it half open. The small space looks a grave, as if some one had

been buried there after sacrifice.

“Returning to the west end of Stemster Loch, you observe a small stream runs

out of it down to Loch Rangag. This little stream I traced from the one loch

to the other. I traced it very patiently, and was rewarded and delighted.

“Where the bum runs out of Loch Stemster, there has been dug a sort of

watercourse, and a sluice-gate has been put in. They have cut through the

strata, hard clay stone, and bituminous stone, with the same abrupt dip to

the east. You go down the stream, over the edges of the strata, still

dipping east. On and on, and still the dip is east. Going on, over their

edges, you are arrested by a bed tilted south ! Dip south. Close in contact,

you find a bed on end!—broken fragments, angular, gneiss-looking, hard,

bound together by three seams of lime crystallised. Disturbance and even

trituration have been at work. On a little. The strata wheel round again to

an easterly dip. Down, down, and down —down even to the Mill, and even below

the Mill; and the same beds, bed over bed; what a pile! The distance between

the two lochs is about a mile on the map. During half of that mile, you

descend the strata, bed upon bed, stair-like; about 2625 feet. Then up above

Loch Stemster another hill overlies all this thickness of rocks ! You are

perfectly safe in estimating the thickness of the Slate beds.”

After he had made his observations, he returned home with all speed. The

bread must be made and baked, and the bread must be sold. His hard day’s

work in the mountains was followed by a hard day’s work in the bakehouse.

“A long period elapsed before Dick again corresponded with Hugh Miller. The

latter was editing the Witness, and preparing his admirable book entitled My

Schools and Schoolmasters. Dick had again returned to his study of botany.

But the correspondence seems to have been resumed towards the end of 1854.

In a letter written by Dick to Hugh Miller, he says, “ When Satan once

appeared where he ought not to have been, and was asked ‘ WLence comest thou

? ’ his answer was, ‘ From going to and fro in the earth, and walking up and

down in it.’ Now, what could you expect from any deil’s bairns but only a

reflex of their father’s conduct ? I too have been going to and fro in the

earth, and walking up and down in it; with this difference, however, that I

have had the very best intentions. And though Satan’s palace chambers are

said to be paved with such, I hope he shan’t have any of mine for

flagstones—more particularly as my acts have been of the most innocent

kind,—scorning to mock the use of any living thing,-/-not even rudely

crossing the stray ideas of any fellow-geologist.

“I have been admiring the fashion of the grass of the field; not only

admiring but collecting it; not only collecting hut studying it. In the

prosecution of the study, I have made hundreds of laborious journeys. I have

ransacked the coast,—rambled inland over moor, mire, and meadow—up hills and

across valleys—peeped into .running streams and stagnant pools, goose-dubs

and dismal lochs. Finally, I have been twice on the pinnacle of Morven—the

Mont Blanc of Caithness.

“Nor has the peculiar study that you favour been forgotten. I have made many

journeys expressly in search of fossils, or to examine some particular

stratum, I have regularly visited the boulder clay after rains and

storms—kept a keen eye after all the slate quarries— and even spent days in

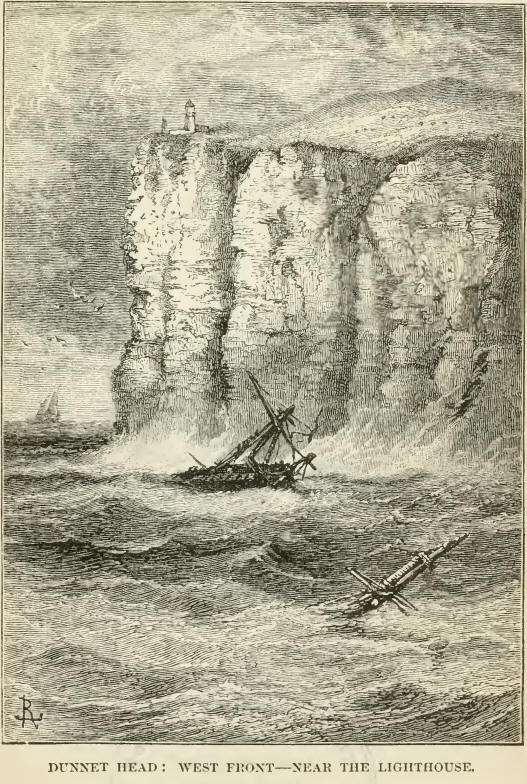

scrutinising Dunnet cliffs. True, in March 1854, clambered down the West

Front, more than two hundred feet, and examined, searched, and hammered for

hours; and my only reward was a curious thing, which is still a problem.

Splendid sections are those cliffs. How strange one feels, crawling along

their feet, and looking up their perpendicular height! What mites, what

trifles we are amidst the might of earth and the vastness of oceanI”

Hugh Miller was at this time very much annoyed at the leaders of the sect of

which his newspaper was the organ. “I see” says Dick, “that you are not in

heaven as to peace any more than I am. Yet I candidly say that it is very

hard that you cannot enjoy yourself for one day among the rocks, without

being assailed for it by ignorant W. W.’s be they clerical or not. Great

stir about tyrannical Popery at present ; but query—may there not be among

ourselves Moderate Popes, Free Popes, and such like ? Plenty, I guess. The

divine right of ruling is worth ten times the stipend.”

In acknowledging the receipt

from Hugh Miller of some papers containing an account of the meeting of the

British Association at Edinburgh, Dick says—“ These papers are not thrown

away. They shall be duly pondered and considered—ay, on mountain tops, even

at early dawn, or sober eve, when the twinkling stars and the soothing winds

tell their own tale of nature’s happiness in their own dear way.

“It is a blessed thing that creation smiles or frowns, laughs or is sad,

just as we are content or otherwise. Every man according to his ‘gift.’

Sooth to say, I am one of those whose faith is too weak to see every one of

the many twinkling orbs that bedeck the vault of heaven —the abodes of

beings who suffer and of beings who rejoice—of beings who are saved, and of

beings who are lost. Ho, no! I have thrown Calvin’s theory to the winds.

There are as many Gospel theories as there are geological; and all are at

liberty to behold their own likeness in their own mirror. Only one thing. If

divines have for centuries been preaching nonsense about the creation of the

world and of man, what confidence can an ignorant man have in their findings

and interpretations of other parts of the same writings^ equally full of

interpretations, corrections, and amendments? I know what I say.”

The correspondence proceeds at intervals, until the death of Hugh Miller,

which took place on the 24th December 1856. He was then preparing the last

sheets of the Testimony of the Rocks, which was published at the beginning

of 1857. Dick was of opinion that Hugh Miller published the book quite as

much to please the dominant religious party in Scotland, as to satisfy the

convictions of his own mind. Indeed, he traced the beginnings of Hugh

Miller’s insanity to the over-stimulation of his brain, for the purpose of

meeting the exigencies of his position as a scientific man and a religious

journalist. Some time before the sad catastrophe of Hugh Miller’s death, he

mentioned to Professor Shearer a curious symptom, indicative of commencing

insanity in this gifted man.

The following are Professor Shearer’s words :—“I had an interview with Mr.

Dick in the inner shrine of his daily labours—his bakehouse. This was

considered a high mark of his consideration; and indeed his manner was

perfectly cordial and natural. Our conversation naturally turned upon his

friend Hugh Miller, then not long dead, and to his books. His powerful and

brilliant effort to reconcile the scriptural account of creation with

geological science, Mr. Dick considered a failure. At the same time, he

strongly maintained the doctrine of successive creations of animated beings,

though he appeared to have no confidence in the Darwinian doctrine of

development. Pointing to the sketches of the Greek boy and the ape on the

walls, he asked, ‘ whether that could come out of this ?’

“Returning to Hugh Miller, I naturally expressed my sorrow that a life so

brilliant and valuable as that described in his Schools ancl Schoolmasters,

should have ended so sadly. ‘ Ah, poor Hugh!’ said he, ‘ I knew him well.

His life, as he could write it, would be as interesting as a romance. But I

am not at all astonished at the way it ended. His mind was touched somehow

by superstition. I mind/ he continued, ‘ after an afternoon’s work on the

rocks together at Holborn Head, we sat down on the leeside of a dyke to look

over our specimens, when suddenly up jumped Hugh, exclaiming, The fairies

have got hold of my trousers! ’ and then sitting down again, he kept rubbing

his legs for a long time. It was of no use suggesting that an ant or some

other well-known ‘ beastie’ had got there. Hugh would have it that it was ‘

the fairies ’! ”

“When the news of Hugh Miller’s death came,” said Dick to his sister, “I

thought it was the end of all things. I was more shocked than I could tell

to anybody. Poor Hugh! I knew him so well! I shall always remember him.

Indeed, he is now, and almost always, with me. I cannot look on a stone

without thinking of him. I am not likely ever to forget him. He was sorely

afflicted with his head while he was here, and to such a degree that neither

you nor I can form any idea of his sufferings. Peace to him! He will live

long over all the earth.”

Again writing to his sister, he says, “ Mrs. Miller has sent me Hugh’s last

Testimony of the Rocks. I have read it frequently. It contains a great deal

of good writing; but it leaves the great point as far from being settled as

ever. I am surprised at his mode of handling the two records—the account of

creation in Genesis, and the facts as we actually find them; for it is an

undeniable fact that all our present dry lands are full of dead animals. But

don’t mistake me. Mr. Miller has produced an unmistakably clever book, which

will sell fast and become popular. But it does not solve the great problem;

neither is it in harmony with the account of creation recorded in the oldest

book extant. Nor will it convert geologists, and satisfy those who know

anything about rocks and organic remains.

“Possibly the business cannot be settled in the present stage of discovery,

and friend Hugh had rather too much veneration for sundry great living men,

to strike out a new path amid such an entangling forest of conflicting

opinions. Of one thing you may be sure. The earth, as we have it, was not

made in six ordinary days. The earth is making yet. It is still in course of

creation.” Strange to say, when the Life of Hugh Miller came out, not a word

was said about Piobert Dick. The two had been in communication for more than

ten years. Dick returned to Mrs. Miller all the letters he had received from

her husband, for the purposes of the biography; and more than a hundred of

Dick’s letters were in the possession of the biographer. Dick had given all

his best fossils to Miller. “He robbed himself,” said Hugh Miller, “to do me

service.” Dick worked night and day to enable him to illustrate his works by

new specimens. One would have thought that these services were worthy of

some mention in Hugh Miller’s biography. But not a word is said there zs to

Hugh’s greatest helper. |