|

It will be remembered that

Thomas Dick, supervisor, left Thurso in 1834, shortly after his son Robert

had begun business as a baker. Mr. Dick was appointed to the office of

Collector of Customs at Haddington. He did his duty there in a quiet,

unostentatious manner, and gained the respect of everybody who knew him.

After his term of service had expired, he removed to Dovecot, Tullibody,

where he ended his days in peace and quiet.

Robert Dick continued to keep up a correspondence with his father, though

none of his letters have been preserved. The last letter of his father (22d

April 1846) informed Robert of his last illness. “My complaint,” he said,

“is in the heart. I am sometimes alarmingly ill. At other times, though very

weak, I am able to be up. . . . There is no prospect of my recovery. I have

been preparing for the last change, and have laid my hope on the Lord Jesus

Christ. . . . Dear Robert, pray for me. May the blessing of God attend you

through this life, and afterwards receive you into glory.”

This was his father’s last blessing. He died five weeks after. His son

preserved the letter. He writes upon it, “I have laid it amongst my mother’s

hair.”

Robert was not able to attend the funeral. He was too poor for that. The

journey was long and expensive, and there were no railways in Caithness at

that time. Besides, he did all his work with his own hands. He had neither

journeyman nor apprentice. His only helper was Annie Mackay, his servant.

His sister Jane, however, went from Haddington to Tullibody, to be present

with the family at the time of Mr. Dick’s funeral. After her return home—for

she was then married—he thus wrote to her:—“I have thought that it may

perhaps lighten the distress which you suffer from the decease of our

father, if I should write you a few lines,—not that a flow of words is the

best source of comfort in a case such as this. Resignation to the will of

God will avail much more. I hope you will see it to be your duty to bow in

quiet and patient submission, looking forward with the eye of Faith to that

better world, where, after a few years, you will meet your father again.

Your mother is also there. Those who remain behind must toil on, and abide

their time, neither murmuring nor desponding at the ways of the Supreme

Disposer of all events, whether prosperous or adverse.

“These events create sad blanks. The mind for a time will be hankering after

what is gone. But new affections spring up and entwine themselves round the

soul, hiding if not healing the wounds. Time will roll on, and then we shall

be here no more. This is all that has been and will be. One generation

cometh, and another goeth. The Framer of all things alone is subject to no

change.”

Robert Dick also kept up his correspondence with his old master, Aikman, at

Tullibody. In the year following his father’s death, Aikman told him that he

was about to retire from business,—“that he had not yet advertised the shop

and bakehouse, but intended doing so. It would be a good opening for an

active man, as he was now baking about 20 bolls of wheat every week, with

three men and a boy.”

This was doubtless intended as a hint to his correspondent to buy the

business, and thus enter into a thriving trade. But Dick had no money to

spare for the purpose. His business at Thurso was only paying expenses. He

did not save money. What he could spare from his ordinary wants, he spent on

books.

Competition was also beginning to tell upon him. Although there were only

two bakers in Thurso at the time that he commenced business, there were now

several. Every new baker served to diminish his trade. No increased exertion

could make up for the loss. The town was small, and the people’s wants were

few. When the bakers amounted to six, Dick said “it was like half-a-dozen

dogs worrying over a very little bone.”

Dick’s business was also to a considerable extent diminished by his not

going to “the Kirk.” When that is known of a man in a small town in

Scotland, it goes very much against him. The “fear o’ the folk” is very

great there. Conformity is insisted on. A man must be what other people seem

to be, or he is looked upon as a sort of reprobate.

We have been told why Dick abstained from going to church. Miss Dick, his

half-sister, says that the singing caused him giddiness, and that he had

some feeling in his head which prevented him sitting in church. Another says

that he considered the sermons which he heard to be only “cauld kail het

again;” and that he could study the Bible and read his sermons just as well

at home. Indeed, his library was full of religious works. He had seven

Bibles and a Latin Testament, with various commentaries on the Scriptures.

His library included a set of Bible maps, and the works of Josephus,

Mosheim, Locke, Kitto, Hervey, Wardlaw, and others.

Dick had been a diligent attender of the Established Church until the

Disruption in 1843. He had a wonderful memory, a large vein of humour, and

even a good deal of mimicry. He could, upon occasion, give a head or two of

the discourses; and for that matter, a whole sermon of several of the

ministers of the town and neighbourhood, with the gesture, and accent, and

peculiarities of each, to perfection. His old servant used to say, that if

she wanted a sermon she had not far to go to get one. “Tae hear my maister

sometimes,” she would say, “you wud think you were hearing Mr. Cook of Beay

or Mr. Munro of Halkirk preaching frae the tent on the Thursday o’ the

Sacrament.”

But we have received another account, from a veriL able person, as to the

reasons why Dick ceased to attend the kirk on Sunday. When the Disruption

occurred, almost all the congregation went out with Mr. Taylor, and set up a

church of their own. But Robert Dick, who cared very little for religious

politics, or even for parliamentary politics, remained where he was. “I am

very well satisfied,” he said, “ with the church of my fathers.” In fact, he

“stuck by the waas.” It is even said that at this time, for want of leading

men in the church, it was proposed to make Robert Dick an elder. But a

circumstance shortly after occurred which had the effect of sending him away

altogether.

It seems that one day Dick met in the street a man named Geddie, a barber

and shoemaker in Thurso. The man was loquacious and locomotive. “Ah!” said

Geddie, “that was a fine sermon o’ the minister’s yester day.” “Yes,” said

Dick, “but he was perhaps a weo thocht indebted to Blair’s Sermons and

Hervey’s Meditations.” “Ay, was he?” said the barber. Away the little

busybody went, and spread the report among the tattle-mongers of the place.

The barber’s shop is always the centre of gossip. The report about Dick and

the minister soon came to be known. Of course, it reached the minister’s

ears.

Dick was at that time accustomed, being an early riser, to get up on fine

Sunday mornings and take a walk along the sea-shore, with the magnificent

prospect of Dunnet Head on one side and Holborn Head on the other, with the

Orkney Islands in the distance; and a glorious walk it must have been on an

early summer morning. Dick got home by breakfast time, and then he prepared

to go to church. But one day he got a sermon which made his ears tingle. It

was upon the awful crime of Sabbath-breaking—upon going about on the Sabbath

day, and wandering in pursuit of “science, falsely so called.”

Dick could not mistake the application of the sermon. He felt that it was at

him the minister was preaching. If it was not intended for him—as we have

been assured —at all events he put the cap on. “Well,” he said, “I’ll never

more be preached at. Religion is not The Kirk: neither is it in the

preaching of one minister or another. I’ll stay at home, and do my religious

services myself.”

The person who gave us the above information was one of Robert Dick’s

intimate friends. He says Dick was a thoroughly religious man, though he

ceased to attend the Established Church. He was invariably kind, benevolent,

and helpful. And perhaps he entertained deeper thoughts about religion than

anybody in the parish, not even excepting the parish minister himself.

Dick himself told the same story to Mr. Peach. He said that having been shut

up in the bakehouse during the greater part of the week, he thought it was

for the benefit of his health that he should take an early Sunday morning’s

walk; and that it was an interference with the liberty of the subject to

preach at him in that way. Mr. Peach further says that he always kept a

solitary service in his own house, reading the Bible, and the commentaries

thereon.

One Sunday morning Mr. Peach called in upon Dick, having walked over from

Castletown for the purpose.3 He found Dick reading the Bible, with Sharpe’s

translation of the Hew Testament from the Greek of Griesbach, and comparing

one with the other. “Ah!” said Dick, on seeing Mr. Peach coming in, “you

never had the Shorter Catechism knocked into your head as I had during my

youth.” After further conversation, he said, “After all the translations of

the Bible that have been made, there is none like the old translation. It

has the right ring about it. And then, it is so connected with all the

associations of our early home life.”

The people of Thurso, however, could never understand Dick. They saw him

going out at all times with his hammer and chisels, and bringing home loads

of stones. What had he been doing? Had he, like Hugh Miller, been “seekin’

siller in the stanes”? or had he been digging holes in the ground to bury

the gold he had made by his trade ?f In these respects the people of Thurso

were altogether at sea.

Dick went on with his geological investigations. All his treasures were sent

to Hugh Miller. He kept duplicates for himself, and by degrees collected a

rich repository of fossils. He stored them in his upper room, where he also

kept his best books. To help Hugh Miller, he began his researches into the

boulder clay4 of Caithness. “I had seen the boulder clay,” says Hugh Miller,

“characteristically developed in the neighbourhood of Thurso,—hut, during a

rather hurried visit, had lacked time to examine it. The omission mattered

the less, however, as my friend Robert Dick is resident in the locality; and

there are few men who examine more carefully or more perseveringly than he,

or who can enjoy with higher relish the sweets of scientific research. I

wrote to him regarding Professor Forbes’s decision on the boulder clay of

Wick and its shells; urging him to ascertain whether the boulder clay of

Thurso had not its shells also. And almost by return of post I received from

him, in reply, a little packet of comminuted shells, dug out of a deposit of

the boulder clay, laid open by the river Thurso, a full mile from the sea,

and from eighty to a hundred feet above its level. He had detected minute

fragments of shell in the clay about twelve months before; . . . but his

dread of being deceived by mere surface shells, carried inland by seabirds

for food, prevented him from following up the discovery.”

But now that Hugh Miller inquired about the existence of sea-shells in the

boulder clay, Dick proceeded to follow up his investigations with the

keenest interest. He visited every locality in Caithness where boulder clay

existed. He went as far as John o’ Groat’s and Freswick in one direction;

and to Dunbeath, at the southern limits of the county, in the other. He did

the most of his journeys at night; sometimes walking in the dark, at other

times in bright moonlight. He seems to have been intensely interested in all

that he did. Everything was to him new and wonderful. His delight was often

like that of a thoughtful child, in seeing further into the mysteries of a

piece of fine mechanism.

“It appears to me,” he said in a letter to Hugh Miller (1st September 1848),

“that the best way of answering your queries, will he to relate in a plain

and simple way the various truths which have dawned upon my astonished mind,

during my rambles of the last few weeks.

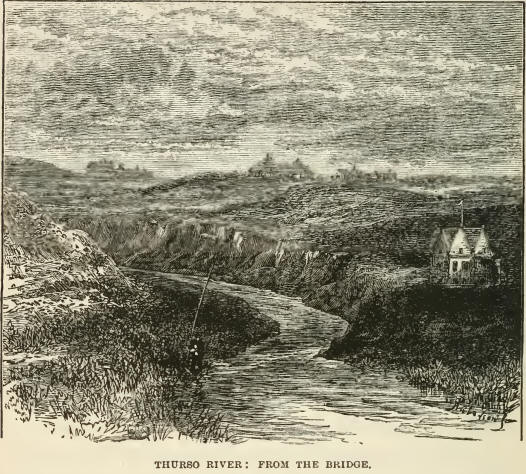

“Few are acquainted with the peculiar features of Thurso river. Few are

aware that, in many places, as it nears the sea, it has scooped out its

course deep in the blue boulder clay. Hear the town, on the west or left

bank, a bed of this blue clay is seen within a stone’s cast of the bridge.

On the east you see it at Mill Bank; and on both sides, after that, an

immense mass runs on, almost continuously, four miles inland, until at

Todholes it becomes low, and on a level with the surrounding fields.

Throughout its whole extent it almost invariably presents the same

characteristic marks—pieces of blue stones, granite, gneiss, and such like.

“Hot long since, the Thurso

East Salmon Fishing Company ran a dyke or wall across the river; and in

consequence of the openings left at the south-west end, the waters of the

river, when the rains fell and the floods rose, rushed with great

impetuosity and violence on the end of a hank of blue boulder clay,

undermining and bringing down large pieces of it. After one of these

slippings I found the first fragments of shell. A piece of stout Cyprina was

found sticking in the clay; and various shell fragments, with a considerable

sprinkling of pieces like grains of oatmeal or pinheads.

“At another part of the river, a large piece of boulder clay had fallen,

near Juniper Bank House; and here I detected fragments of shell, and that

fragment of Bent-alium which I sent you. The exposed portion of the boulder

clay is here eighty feet in height above the river-level; and the river here

may be about twelve feet above the sea-level.

“On turning to Brown’s Elements of Fossil Conchology, I find a figure of

Dentalium; but in the letterpress description of it, I do not find any

mention of its ever having been found in the blue boulder clay.

“On a future evening I examined the blue boulder clay at Scrabster along the

bay. I detected fragments of shell here again, but not so plentiful as up

the river.”

In a future letter he says :—“On the river-side, right beneath the House of

Geise, there is a rather high exposed section of the blue stony clay; and

here again I found shell fragments. I had a good piece to walk—through

grass, heather, bracken, asphodel, and rushes—before I met with another

slope; and here also, again and again, I met with shell fragments.

“A fine section presenting itself on the eastern side of the river, I

stripped and waded through the river. Here again, my now familiar

acquaintances presented themselves; and here—what I had not met with before

—I found a piece of chalk flint. The flint was sticking in the clay.

“I was now at ease regarding the fact of the shells, but was rather puzzled

with the flint. I sounded my savants, as to their acquaintance with this

unlooked-for fairy. I showed it to them, and asked them if they had seen

such a thing up the country; when they both— the old one and the young

one—answered ‘Yea’ They had found them when digging, and the old people told

them that fire was in them, and that they were commanded in all haste to

bury them again, for fear lest the cattle should get a shot!

“Another thing may be added. I know that farmers hereabout use seaweed as

manure, and that shells of Fusus, Littorina, Purpura, Patella, etc., find

their way up the country along with the tangles; and that cockles and

periwinkles are scattered everywhere. I have even found them far inland, and

away from cultivated land. The sea-mews, when hard pressed in winter, eat

turnips, sea-shells, whelks, and Purpura lapillus; and flying far and near,

disgorge the shells in a half-digested state. Therefore, I should not attach

any importance to marine shells on the surface of the most solitary and

unfrequented moor in the county. But when I find marine shells from twenty

to sixty feet deep in the boulder clay, the case is completely different.”

On another evening, while searching with his pick among the boulder clay

along the river side, he met with an almost entire Turritella5 amidst many

other pieces of shell. He had been a shell-collector for fourteen years, hut

had never met with the smallest fragment of a Turritella until the previous

spring, when he found a damaged fragment near Castlehill, Dunnet sands. “You

may therefore,” he says, “judge of my joy in finding one in the boulder

clay. They are abundant, I know, in the British seas, but somehow, owing to

the set of the currents, they are never thrown on Thurso shores.”

On the following evening, he again set out to examine the blue clay, and

found a fine section at Thurdistoft. A large mass of clay and stones had

fallen down the bank. The stones from the blue clay differed from those of

the red. He had before been at Weydale, up the country, and at the quarries

on the hill of Forss, to detect glacial action on the surface of the rocks.

In both cases he failed. But here, among these fallen stones, he for the

first time detected signs of glacial action in four separate instances.

“I now,” he says, “put off my shoes, and, despite the ‘ water kelpies/ took

the ford and pushed on to a fine section on the east side. I again found

shell fragments. My pleasure was great. I pushed on, and next found a very

high section opposite the Bleachfield, on the east side. I found shell

fragments here too. My pleasure was doubled and trebled. ... I was joined by

two boys, who thought it capital sport!

Dick continued to walk early in the morning and late at night in search of

his marine shells. One morning he found an entirely whole valve of Venus

casina. He found at one place on the river-bank a black band or belt running

diagonally in a waving manner across the boulder clay. Above it, the clay

was reddish; below, it was blue. On taking part of the black belt into his

hand and rubbing it, it felt like fine clay and fine sand intermixed. “Am I

to infer,” he said, “that the wavy band arose from the sea ebbing and

flowing alternately over the ordinary boulder clay beneath it? And then the

reddish clay, so different from the clay beneath the black belt. Just as if

the abrading or grinding forces had ceased for a time, and then set to work

again.”

He was soon able, by his unintermitting exertions, to determine whether the

sea had once washed over the county of Caithness.

“In these days of hasty revolutions,” he says, “my opinions since yesterday

have changed. I am now enabled to answer the question which I put to you as

to whether there was a sea here before the deposition of the boulder clay.

“This morning, on clearing away the clay from my shell crumbs from Harpsdale,

I found a piece of the Common Mussel and a piece of the Rock Whelk—Pur-pura

lapillus.”

There was no doubt about it. Not only had the sea covered Caithness, but

ponderous ice-rafts had gone grating along the mountain valleys, grinding

the rocks into clay, and dropping the boulders which they contained along

the sea-bottom as they sailed along. Wherever he went Dick found shells

among the boulder clay— Cyprina, Venus, Turritella terebra, Mactra, and

several species of the genus Tellina.

One day, towards the end of September 1848, Dick went to Harpsdale, about

two miles up the Thurso river. “At Harpsdale,” he says, “in the boulder

clay, marine shell fragments are to be had in abundance. I lingered by this

delightful section for about an hour.” He speakg of the boulder clay as if

it was a lover he was lingering for. He went still higher up the river that

day to Dale House—crossing the river from time to time, startling the wild

ducks, and inspecting the boulder clay in all its windings.

Dick found fourteen shells of the existing races which he had extracted from

the boulder clay, and he had no doubt that this number might have been

doubled. He says—“A list of these shells is necessary, not only to mark my

present success, but also to stimulate me to further efforts.” He

accordingly subjoined a list of the shells he had found, and sent it to Hugh

Miller. “Thin shell valves,” he said, “such as Tellina, have been found

entire. Pieces of Cyprina are by far the most abundant. But I suspect that

it will not do to say that it was owing to their superior strength—their

strong construction—that they are found so very abundant. Mactra and Tellina

have received slight damage; small young Crassina (a month old?). have

withstood the fearful shock of mountain waves, of dashing icebergs grinding

and pounding, whirling about and reeling like playthings —seas charged with

mud, and stones of stupendous weight; all these have been tossing hither and

thither, ebbing and flowing, and the earth reeling; and yet, a diminutive

little thing like this now lying before me has been preserved! Amazing! I

have met with many stones in the boulder clay grooved and scratched and

rubbed in the strangest way imaginable. For the presence of these stones

where they now are, I think the glacial theory is the most likely.

“I have found gneiss, light blue kind of grauwacke, oolite, and oolite

conglomerate, in the clay. I know of no rocks in situ to the west similar to

these. The blue clay and dark clay is undoubtedly derived from the ordinary

rocks of the county. It is found in various degrees of purity, but is in

general one confused jumble, and as hard rammed as if a giant had used one

of the Stacks of Duncans'by as a paving hammer,”

|