|

Robert Dick, by dint of

continuous industry, was gradually acquiring a notion of Caithness geology.

His knowledge was for the most part derived from direct personal

observation. He never accepted a statement without having verified it

himself. He saw with no man’s eyes but his own; he thought with no man’s

brains but his own. Thus what he did know was thoroughly exact, accurate,

and reliable.

As you proceed from letter to letter, in his communications with Hugh

Miller, you see him unlearning his old views and learning new ones. Every

ramble throws some new light on the geology of Caithness. He notes down

everything that he sees. About the dip of Caithness rocks, his observations

are for the most part at variance with the views of his “superiors,” his

“masters in geology.” Nevertheless, he notes down his own facts, and no

doubt they will by and by be confirmed and adopted.

He was very cautious in adopting conclusions. He must first be quite sure of

the premises. He found many writers on geology starting with a theory and

then making the so-called facts fit into the theory. “Here has been some one

writing upon the geology of Caithness,” he said. “His writing is very good,

but his premises are incorrect. He cannot have seen the rocks, except from a

gig, when he passed along the road; and now he drags them in to elucidate

his theory. When I want to know what a rock is, I go to it. I hammer it; I

dissect it. I then know what it really is. I object to this eternal

theorising. My idea is that we know very little of geology, yet these men

have got it dignified by the name of a science. The science of geology! Why,

don’t they see that there are only a very few exposed rocks which we can

study. It is only a small bit of the crust of the earth that we can inspect.

What are the rocks that we can see, compared with the immense mass lying

underground, or forming the ocean bed, which we can never see ? No, no; we

must just work patiently on, collect facts, and in course of time geology

may develop into a science.”

Dick even found that some of the fossil fish and fossil branches that he had

found in the course of his investigations were turned against himself. He

had sent a fossil branch, which had been found in a Caithness quarry, to a

friend in the south, thinking it to be of value. He was afterwards surprised

to find an engraving of the fossil branch given in a geological publication,

with an amount of letterpress, arguing out a theory which Dick had expressed

himself as decidedly opposed to. Not only was the theory incorrect, but the

fossil was misengraved, having received additions which were not warranted,

and illustrated by sections which in his opinion were impossible. In short,

it was twisted, like many a fact, to suit a theory, and Dick was indignant

that a fossil furnished by himself should be used for such a purpose.

It will be observed that Dick’s first study in geology consisted in

observing the dip of the strata round the Thurso coast, from Dunnet Head to

the end of the Hol-bom rocks. He did this with great care, and indicated the

faults, disturbances, and fossiliferous rocks, with their various dips, in

the letter he sent to Hugh Miller in April 1845. He found many of the rocks

abounding in dead fish, quantities of scales, heads, bucklers, and fossil

fish, sometimes in great confusion. Sometimes he found them in abundance on

the top of the highest rocks at Holborn Head. How came they there?

This led him into a consideration of the causes of the abundance of dead

fish in a fossil state on the shores of Caithness. It was clear that the

northern part of the county, where the fossil fish so abundantly exist, had

at one time been entirely under the sea. It had formed part of the bed of

the ocean. An upheaval of the bed occurred, when or how was not known. The

multitude of fishes were caught as in a trap. They were smothered amidst

thin clay. They died in agonies. Hugh Miller says—“The figures of the fossil

fish are contorted, contracted, curved; the tail in many instances is bent

round to the head, the spines stick out, the fins are spread to the full, as

in fishes that die in convulsions. The attitudes of all the Ichthyolites on

the platform of death, are attitudes of fear, anger, and pain.”

The clay formed, layer upon layer, on the fishes, and was transformed by

pressure into flagstones. The process of depression and elevation may have

been repeatedly performed, but every elevation brought up from the sea

bottom dead fish without end. In fact, the commercial value of Caithness

flags consists in the amount of dead fish they contain. “Thurso is built of

dead fish,” said Robert Dick; “and the capitalists and labourers are also

maintained by the same article.”

Sir Roderick Murchison says of the flagstones of Caithness, “that they are

highly valuable for many uses, and must prove eminently durable from the

nature of their composition. Their well-known durability is attributable, in

part, to the large amount of bitumen they contain, which has been produced

by the abundance of fishes which existed at the time those rocks were

deposited, the fossil remains of which still abound. Tar and gas may be

distilled from them.” Hugh Miller also says —“The animal matter of the

Caithness Ichthyolites is a hard, black, insoluble bitumen, which I have

used more than once as sealing-wax.”

But the geological formation of Caithness was still in progress. These dead

fishes existed long before the appearance of man on the earth. If we stretch

our view over long intervals, it will be found that, in consequence of the

depression of one portion of the earth’s crust, and the elevation of

another, what has at one time been dry land becomes covered with sea; and

what has at one time been sea, at another becomes dry land; and that, partly

in consequence of the eccentricity of the earth’s motions, and partly in

consequence of the shifting distribution of land and sea, what at one time

has been tropical, at another becomes arctic, and what at one time has been

arctic, at another becomes tropical.

Astronomers tell us that more than 200,000 years ago, the earth was so

placed in regard to the sun, that a series of physical changes was induced,

which eventually resulted in conferring upon our hemisphere a most intensely

severe climate. All the northern lands of Europe were then covered with a

thick crust of ice and snow. The climate of England and Scotland was what

Greenland is now.

Glaciers, laden with boulders, some torn from the rocks on which they

rested, some fallen from overhanging heights, flowed down the valleys,

leaving their ice-tracks along the sides of the hills. When the glaciers

melted, they dropped the boulders which they contained, either on the land,

or in the sea, far away from the place from which they had been reft from

the rocks. Then was laid down the boulder clay, consisting of an

agglomeration of ground-down rocks of various kinds, old red sandstone,

chalk, or coal, interspersed with boulders, pebbles, and sometimes shells.

There must have been constantly recurring alternations of climate, from

arctic frost to tropical heat, though separated, it might be, by hundreds of

thousands of years, before the dry land was prepared for the occupation of

man. Again, every bed of coal presumes an elevation of the land, and a

subsequent depression. Near Newcastle, there are numbers of these beds, some

of them from eight to ten feet thick. These successive beds of coal consist

of the remains of peat mosses, ferns, jungle, cypress swamps, and forest

growths. They were either submerged where they grew, or were drifted into

seas of deposit. When compressed by the superincumbent strata of sandstones,

limestones, shales, mudstones, and ironstones, they formed the coal fields

of every country. Then, at last, the present land and the present sea took

their places, and man entered on the scene.

Full of curiosity, or perhaps full of the desire for knowledge, Dick

proceeded, in course of time, to look into the geologic formations of the

ground on which he lived. He dug into the rocks, inquired into the nature of

the soil, and found many things which excited his surprise and his wonder.

He found many dead things under his feet—dead foliage, dead ferns, dead

seaweed, dead fish, the dead remnants of chaos.

Such was the subject on which Robert Dick was now spending the remnants of

his spare time. He not only spent his days but his nights in his search for

dead objects. He himself was not before the public, but Hugh Miller was.

Hugh was the editor of the Witness newspaper, in which he entered all that

he knew about geological matters. Accordingly Dick sent all that he

discovered during his rambles to his friend at Edinburgh. Here, for

instance, is a bundle of his findings, which he sent to Hugh Miller on the

21st of July 1845 :—

“I send a stone, with a fossil fish in it, from Weydale; a stone from the

salmon cruives in the Thurso river, with a fish on each side of it; a stone

from the little burying-ground of Pennyland, with a bit of fish on it; a

stone from the burn of Scrabster, with a fish wanting the head on it; a bone

or two from the extreme point of Holborn Head; a fish, a stone or two from

the fish-bed, Holborn; and some bits of fish from Brims. Some bones from

Thurso East—one, two, three of this form [giving a drawing], and a fragment

of a skull-cover of great strength, but not so strong as the monster plate I

sent you; but the triangular knob thus fully to confirm you in the faith of

my report of last year. The fragment is altogether of a massive appearance.

I am much chagrined at my ill luck in not finding a whole fish of

respectable size. I am not, however, cast down, but may yet be triumphant.”

Hugh Miller received with

gratitude the fossil fish sent him by Dick. He also referred to them in his

articles in the Witness, and mentioned Dick by name, as the discoverer of

the principal fossil fish. Dick had no desire to appear before the public in

this or any other way. He was an extremely shy man. Some who did not really

know him, thought him morose. But he was nothing of the sort. He enjoyed

science merely for its own sake, and it always gave him the greatest

pleasure to hand over his fossils to others who could make use of them, and

bring them under the notice of scientific men.

Hence, in the letter to Hugh Miller accompanying the above bundle of

fossils, he says :—“Your letter, with the 10th and 11th Geological Rambles,

came safely to hand. That of the 11th arrived this morning.* I turned to it

without a moment’s delay. I had not read very far when I had a notion of

what was coming, and the perspiration began to rise profusely from my brow.

. . . Seriously, nothing could be better handled than your ingenious mode of

broaching the subject, nor exceed your masterly manner of carrying it

through. . . Only, like a good man, do not speak so often about me by name.

I am a quiet creature, and do not like to see myself in print at all. So

leave it to be understood who found the old bones; and let them guess who

can.”

Dick again repeated his invitations to Hugh Miller to come to Thurso, and

see what he had been doing on Holborn Head, in Thurso East, and at Dunnet

Head. But in order to explore the country further, he went inland to see

what had been found in the flag quarries at Weydale and Banniskirk. He had

been to Weydale several times, and made the acquaintance of a quarry-man. He

had made an appointment to visit him on a certain day, and, as Dick was a

most punctual man and kept his appointments to a minute, he accordingly made

his appearance at Weydale.

“As I drew near the place,” he says, “the auld bachelor came out, pipe in

cheek, and sitting down on a stone, he made a motion for me to come and sit

down beside him. ‘ I saw you coming,’ he said, * but I thocht you wudna come

the day, it was so blawey.’ ‘Oh,’ said I, ‘ I always keep my word, blawey or

no. Did ye tirr a bit?’*f- ‘No, man,’ said he, ‘the grun was so

21st July 1845.

Work a bit hard that feint a bit o’ the pick wud go through it. The gran’s

like iron. But/ he added, ‘I’ve got a fish! ’ 'Have ye?' said I. ‘Yes' he

said, ‘ oot o’ anither place. Ye can see it in the barn.’ And away we went

to inspect the fish in the barn; and there it was, spread out on the clay

floor. ‘See!’ said he. ‘0 man' said I, that’s grand, it’s a new kind’ [Dipterus].

It had been much wasted ere it was buried up in the mud; the tail rays were

all scattered; the head plates were spread out; but a piece of the body was

standing up wonderfully full and round.

“‘See' said he again, ‘there’s a head!’ It was that of a Diplopterus—much

broken, but of a good size. ‘ I must see the place from which it was taken/

said I. ‘ Come away then.’ So, shouldering a pick and spade, away we set.

About three good stonethrows from the burn, we came to what some people had

been trying to make a ditch—rough and rude—and in the ditch was a rock, and

in the rock, fish and abundance of loose scales. But the fish are much

wasted. We worked at the place an hour, but did not get one fish that would

bear carrying away. We saw plenty of broken Diplopteras. I cut my hand and

broke my chisel, and then left the spot, and went back to the burn, where I

got a few small things.

“If you choose to come here and stay three or four days with me, you can

have a fair trial upon a third locality close by, which has never yet been

fairly tested. I will make you welcome to my little house, and you can give

Scrabster, Holborn Head, a trial also —say a day at each. The Diplopterus is

abundant at the Cruives, and Dipterus also.”

The quarrymen in the neighbourhood had now begun to learn the value of

fossils. The publication by Hugh Miller of the specimens of the Holoptychius,

Dipterus, Diplopterus, and other fossil fishes found by Robert Dick near

Thurso, had the effect of sending many fossil-hunters into the neighbourhood.

It was holiday time—the month of August,—and wherever curiosities are to be

found, there is a rush to see them, to find them, and to carry them home as

treasures. Accordingly, when Dick went out fossil-hunting, he found the

strangers from the south very much in his way. One day in August, before the

arrival of Hugh Miller, he extended his investigations to Banniskirk. It was

about eight miles from Thurso, and he had never been there before.

“I have been seventeen years in Thurso,” he said (13th August 1845), “but

never saw Banniskirk. I have been two years a fossil man, but never saw

Banniskirk. You were one blessed week there; but what were you doing?

“Eleven o’clock was ringing this forenoon when I left Thurso for Banniskirk.

I went on and on until I reached it. Most fortunately I directed my steps to

a point of the rubbish which, in my opinion, had not been touched since the

first opening of the quarry. The day was cold and wet, and there I stood

hammering away, as shower after shower went driving by. I was alike

indifferent to wind and weather for some hours.

“When I had tied up my bundle I went to the upper end of the quarry—a good

gunshot off—where four or live men were at work. Accosting them, I said, ‘Is

there any sign of fish with ye? ’ ‘0 no, boy,’ they said, 'ye’re on the

wrong scent. But what wad ye gie for a score o’ themV ‘I don’t know,’ said

I, ‘what wad ye seek?’ ‘Igot five shillings for one? said a buck-toothed man

with a long nose. ‘Ay,’ said I, ‘the siller has been plenty.’ ‘Yes,’ said

another; ‘he was an Englishman ! ’ ‘ Oho,’ said I, ‘ that’s the stuff!

Nothing like

English gold! ‘Yes,’ said he; ‘away wi’ yer scabbit Thurso folk! ’

“‘But,’ said I, growing saucy in my turn,—‘they’re lying in hundreds at

Weydale—in hundreds at Holborn Head—in hundreds at Brims—in hundreds at

Thurso East!’ ‘Ay,’ said they, with a girn—‘Fresh Herring!’ ‘Not so fast,’

said I. ‘What then?’ ‘Fossil bones.’ ‘Not so good as this?’ said they. ‘Yes,

far better,’ and then I came away.

“Dirty, greedy vagabonds. I knew them perfectly well. To get a price for a

few old bones, they have thrown rubbish on the face of the strata. I had,

however, got as many fossil fish as I wanted, no thanks to them.

“I said I had beat you—no harm! Did you meet with any trace of Coccosteus at

Banniskirk? or did you meet with any trace of a Holoptychius? I found both.

I think, if you had met: with any sign of either, you would have mentioned

it. The head of the Holoptychius that I found, was about three and a half

inches wide; a prize from Banniskirk! When I was tying up my bundle, a stone

beside me drew my attention. ‘A gill-cover!’ said I. Lifting my hammer I

gave it a blow. Huzza! Warty! Coccosteus! Huzza again!

“I had a heavy bundle home; and about eight miles to walk.”

Hugh Miller had not yet paid his visit. Dick was eagerly expecting him. He

determined to give Hugh a great treat when he came. He would have a number

of fossil fish for him to dig out with his own hands. For this purpose he

went along the shore, east and west. One day he crossed the stepping-stones

at the mouth of the river, and was passing under Thurso Castle, when Sir

George Sinclair hailed him. Dick was deaf that day. He had lost a whole

afternoon a few days before, by being caught and involved in a conversation

by Sir George. Therefore he rushed up the cliff and disappeared instanter.

But he was not yet at liberty. “One of the salmon-fishers,” he says, “left

his employment, and came and walked sentry over me on the brae head. This

was annoying, ‘but I pushed on. Then some boys fishing cuddins left their

sport and dogged me, tramping almost on my tail. This was horrible. When I

threw a stone aside, they impudently lifted it and looked at it. Wherever I

went, they went also. I saw the snout of a Dipterus; .then two in succession

of the snouts of Diplopterus; then a broken skull-cap, standing out for

about nine or/ten inches, but it is broken,—for some stupid fool had given

it a passing blow—not knowing what it was. I saw it and quaked, for the boys

were still behind me. I did not betray myself, by look or by sign. Then I

got angry, and ran away at my utmost speed.

“Next day was very wet, but as I was eager to know if my bone was safe, I

put up my umbrella, and walked over. As I neared my prize, I ventured to

reconnoitre. Thief-like, I looked round in every direction, and then moved

forward, and found it quite safe. ... I can now say confidently that you

will have the pleasure of digging out the remains of this Holop with your

own hands at Thurso East. I am very glad!

“I will next go to Holborn Head, pass Slater’s monument, and with a spade

turn aside a piece of the clay and turf, that you may have the pleasure of

striking a passing blow, and get a fossil fish there, also with your own

hands.

“I was at Weydale on the 9th, and managed to ‘tirr a bit.’ The remains of

the Diplopterus are there in abundance; but they are very much knocked

about— heads, scales, gill-covers, bits of tails, and such like. I only

brought off one moderately passable specimen for you.

“I expect that you will strive to drop me a note, as to what time I may

expect you; so that I can have my work snugged, and all in order. I shall be

most happy to see you, and we shall have a Glorious Day! ’

Hugh Miller at last paid his visit to Robert Dick. They had been

corresponding for a long time, but had never yet met. Their meeting was full

of cordiality.

Robert gave up his bed to Hugh, and he was to stay there as long as he

liked. But his visit was to be very short. He had very little spare time at

his disposal. The Witness must be kept up to the mark; and like many other

newspaper editors, he thought that if he remained long away, the world would

come to an end. Then, there was his new book to write, the Asterolepis of

Stromness. Hugh Miller’s first visit to Robert Dick was therefore of only a

few day’s duration.

The weather was fine, and most of their time was spent out of doors. They

walked along the east shore, and along the west shore. First they went with

hammer and chisel to Thurso East, to dig out the Holoptychius, the head of

which Dick had noted only a few days ago. Dick pointed out the bed from

which he had taken the gigantic fossil fish the year before. After this work

had been done, the brother geologists proceeded eastward, Dick pointing out

the scales and teeth, the tuberculated plates, and the coprolites of the

fossil fishes. Hugh Miller afterwards gave a sketch of the coast, of Dunnet

Head on one hand, and Holborn Head on the other, with the Orkneys “rising

dim and blue over the foam-mottled currents of the Pentland Firth.” We have

already given Dick’s sketch of the same view; and we prefer it, as it was

done from the quick

But we quote a passage from Hugh Miller’s description,—a bit of nature

painted by a poet. “We are still within an hour’s walk of Thurso; but in

that brief hour how many marvels have we witnessed! how vast an amount of

the vital mechanisms of a perished creation have we not passed over! Our

walk has been along ranges of sepulchres, greatly more wonderful than those

of Thebes or Petrea, and a thousand times more ancient.

There is no lack of life

along the shores of the little solitary bay. The shriek of the sparrowhawk

mingles from the cliffs with the hoarse deep croak of the raven, the

cormorant, on some wave-encircled ledge, hangs out his dark wing to the

breeze; the spotted diver, plying his vocation on the shallows beyond, dives

and then appears, and dives and appears again, and we see the glitter of

scales from his beak; and far away in the offing the sunlight falls on a

scull of sea-gulls, that flutter upward, downwards, and athwart, now in the

sea, now in the air, thick as midges oyer some forest brook in an evening of

midsummer.”

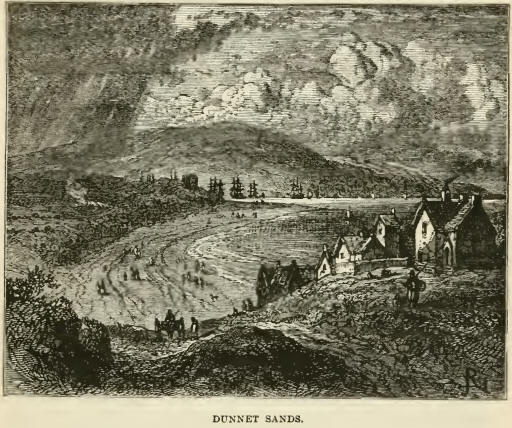

The geologists passed on towards Dunnet Bay. They crossed Dunnet sands, and

at length reached the tall sandstone precipices of Dunnet Head, with their

broad decaying fronts of red and yellow. They had reached the upper boundary

of the Lower red formation, and found it bordered by a desert, and void of

all trace of life. They plied hammer and chisel, but found not a scale, not

a plate, nor even the stain of an imperfect fucoid.

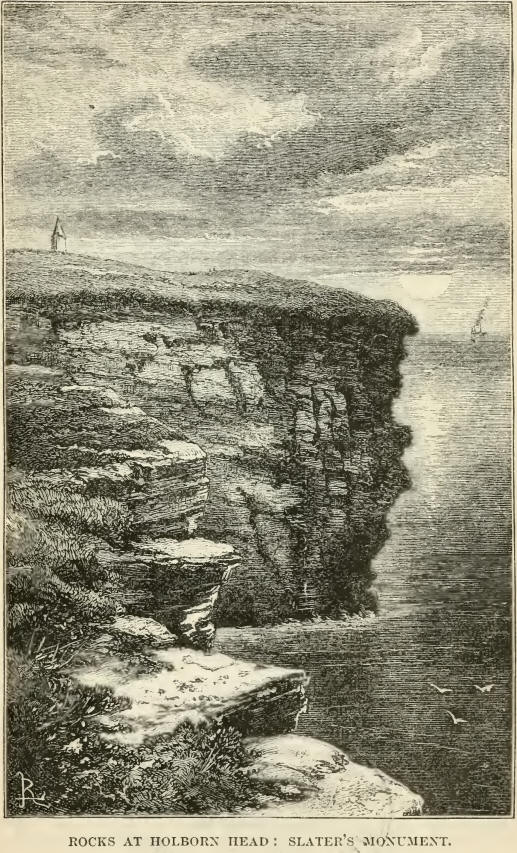

On the following day the brother geologists wandered along the shore of

Thurso West,—Dick pointing out the boulder clay between the Bishop’s Castle

and Scrabster Harbour. They ascended Holborn Head, went along the precipices

to the Clett, after which Hugh Miller chiselled out with his own hands the

fossil fish that Robert Dick had set apart for him. He did not cut his hands

as Dick had done, for Hugh was an accomplished mason before he became a

geologist. There was one particular sight that struck Hugh very much while

standing on the top of the rocks at Holborn Head, and looking down with Dick

into the deep sea-green water, underlying the lofty cliff called “Slater’s

Leap.” Hugh Miller afterwards described it splendidly in his Lectures on

Geology. He says :—

“Perhaps the most striking scenic peculiarities of the Old Red Sandstone are

to be found in its rock-pieces. The Old Man of Hoy, with its rural rampart

of rock-pieces, not unfurnished with turret and tower, and wide yawning

portals that rise a thousand feet over the waves; the tall stacks of

Duncansby, Canisbay, ornately Gothic in their style of ornament, with the

dizzy chasms of the neighbouring headland, in which the tides of the

Pentland Firth for ever eddy and toil, and the surf for ever roars; and the

strangely fractured precipices of Holborn Head, where, through dark crevice

and giddy chasm, the gleam of the sun may be seen reflected far below on the

green depths of the sea, and venerable and grey, like some vast cathedral, a

dissevered fragment of the coast descried rising beyond,—are all rock scenes

of the Old Red Sandstone.

“When I last stood on the heights of Holborn there was a heavy surf toiling

far below along the base of the overhanging wall of cliff which lines the

coast, and deep under my feet I could hear a muffled roaring amid the long

corridor-like caves into which the headland is hollowed, and which, opening

to the light and air far inland by narrow vents and chasms, send up at such

seasons, high over the blighted sward, clouds of impalpable spray, that

resemble the smoke of great chimneys. As I peered into one of these profound

gulphs, and dimly marked, hundreds of feet below, the upward dash of the

foam, grey in the gloom,—as I looked, and experienced with the gaze that

mingled emotion natural amid such scenes, which Burke so well analyses as a

consciousness of great expansiveness and dimension, associated with a sense

of danger,—my eye caught on the verge of the precipice the outline of part

of an old reptile fish traced on the rock. It was the cranial buckler of one

of the hugest ganoids of the Old Red Sandstone, the Asterolepis. And there

it lay, as it had been deposited, far back in the bypast eternity, at the

bottom of a muddy sea. But the mud existed now as a dense grey rock, hard as

iron, and what had been the bottom of a palaeozoic sea had become the edge

of a dizzy precipice, elevated more than a hundred yards over the surf. The

world must have been a very different world, I said, when that creature

lived, from what it is now. There could have been no such precipices then; a

few flat islands comprised, in all probability, the whole dry land of the

globe ; and that emotion of which I had just been compassed, is it not

something new in creation also? The deep gloom of these perilous gulphs—these

incessant roarings—these dizzy precipices —the sublime roll of these huge

waves—are they not associated in my mind with a certain idea of danger—a

feeling of incipient terror, which, in all God’s creation, man, and man

only, is organised to experience? Is it not an emotion which neither the

inferior animals on the one hand, nor the higher spiritual existences on the

other, can in the least feel—an emotion dependent on the union of a living

soul with a fragile body of clay, easily broken?

While at Thurso, Miller fired his friend’s mind with the injustice done to

the poor remnant of the Highlanders who still remain in the far north. Many

years before, the Celts had been driven out of their homes, such as they

were, to make room for sheep, and afterwards for deer. This was during the

time that Sir John Sinclair was so much bent upon introducing the Cheviot

breed of sheep into Scotland The Highlanders were thought to be idle, and

they were accordingly driven away, or forced to emigrate. It was thought to

be “for their good.”

Yet the poor folks did not think it for their good to leave their homes

amongst the hills in which they had been born. But the law was against them.

The chiefs insisted on their pound of flesh, and the Highlanders were

expelled, and emigrated in all directions. If they did not leave after their

notices had expired, their houses were pulled down, and sometimes they were

burnt down, leaving only blackened ruins. One old paralytic woman was

actually burnt in her bed.

In 1795, Sir John Sinclair raised a regiment, the Caithness Highlanders,

consisting of 1000 stalwart men. Ho such regiment could be raised now. The

Highlanders are now in Canada, and sheep supply their places. Emigration

still continued to go on. In 1841 Dick wrote to his sister: “ Emigration to

America is fast thinning the moors of this cold bare country; and soon, very

soon, it will be bare of population with a vengeance. Two ships have already

sailed. A third and a fourth are expected to sail this season. Many hamlets

have been pulled down, and those that have not been pulled down are to let!”

The flag works at Thurso, and of Mr. Traill of Castletown, gave employment

to many of the expatriated clansmen; but still, there were thousands

preparing to set out for Canada and America.

The trouble was renewed in another way when the Free Churchmen dissented

from the Established Church. They could not find sites for their chapels,

and sometimes they gathered together on the verge of a loch, where the

minister could preach to them from a boat. They also assembled in the open

air, along a hill-side, or in a valley surrounded by rocks, where the

minister dispensed to them the Word of God and the Holy Sacrament.

Hugh Miller was editor of the Witness, an outspoken paper, the organ of the

Free Church. Hugh was a great power in those days. He was one of the boldest

writers of his time. His paper spread far and wide the cruelty and injustice

of the Highland proprietors. Here is one of his descriptions, which he wrote

while on his way to meet Robert Dick at Thurso :—

“I have just returned from Helmsdale,” he said, “where I have been hearing a

sermon in the open air with the poor Highlanders. ... I thought their Gaelic

singing, so plaintive at all times, even more melancholy than usual. It rose

from the green hill-side like a wail of suffering and complaint. Poor

people! There stretched inland, in the background, a long deep strath, with

a river winding through it. It had once been inhabited for twenty miles from

the sea; hut the inhabitants were all removed to make way for sheep ; and it

is now a desert, with no other marks of men save the green square patches

still hearing the mark of the plough, that lie along the water-side, and the

ruined cottages, some of them not unscathed by fire, with which these are

studded. . . . The people had a look of suffering and subdued sadness about

them that harmonised but too well with the melancholy tones of their psalms.

There is, it is said, a very intense feeling about them. ‘We were ruined and

made beggars before/ they say, ‘ and now they have taken the gospel from

us/”

And again, at Loch Brora, he says:—“The Loch stretches out in front for

miles, its undulating and winding shores tufted with birch, and here and

there mottled with small green spots that, ere the poor Highlanders had been

driven from home, kept them in oats and bere. . . . I doubt not that the

thoughts of them live, set in sorrow, in hearts beyond the Atlantic.”

When Hugh Miller had left Thurso for Edinburgh, Robert Dick took his pen in

hand, and wrote the following stanzas:—

DONALD’S FLITTIN!

Eh, Donald, man, they’ve served ye sair,

Yeer Hieland chiefs an’ a’,

They’ve brought their sheep, an’ uovvt, an’ deer,

And ye maun gang awa !

Ye focht for them, ye bled for them,

Sae lang’s a sword ye’d draw,

An’ though ye got but little for’t,

Now ye mann gang awa’!

Puir Donald, man, where is he gaun?

His wife and bairnies twa?

“Oh, fient care I,” the laird, said he,

“So that they gang awa’! ”

The wife sat by her cauld hearth-stane,

She couldna thole her fa’ ;

She moaned and sighed, and groaned and grat

She wadna gang awa’ !

The licht was set to theek and roof,

The fire ran up the wa’ !

Alas ! the Hieland mother now

Was forced to gang awa’!

Oot owre the cot, upon a stane

She sat, wi’ bairnies twa ;

Her heart was brak, she could but dee ;

She couldna gang awa’!

He couldna use his dirk the noo,

The laird was right in law ;

Sae Donald gave up house and hame?

And syne he gaed awa’!

Across the seas he dreams o’ hame,.

Far off in Canada ;

But grim and bitter Donald thinks

Of when he gaed awa’ |