|

The coast scenery, east and

west of Thurso, is very grand. On the one side it rises into Holhorn Head,

and on the other into the long perpendicular rocks of Dunnet Head. Holhorn

means Hell’s child, from Holla the goddess of hell, and Horn child. Many a

ship has been dashed against the rocks there. This has probably originated

the peculiar name of the headland.

When a ship in the North Atlantic is caught by a storm, and the wind blows

violently from the west, she is driven towards the rockbound coast of the

Hebrides. If she can weather the Butt of Lewis, she is driven towards the

gigantic rocks of Cape Wrath, which extend for about fifty miles towards

Holborn Head. If she can manage, by backing, to enter Scrabster Roads, she

is safe. If not, she is driven upon the rocks, and utterly destroyed—ship,

men, and cargo.

The faces of the rocks are hollowed into gaping caverns, where the waves

thunder in, and roll along the gyoes far inland. The leap of the waves is

only exceeded by their rebound seaward again. They rush up the face of the

rock like a pack of hounds, and spread themselves along the summit in

blinding showers of spray

As yon stand upon the top of the rocks in fine weather, they seem to

precipitate themselves into the sea,—in many cases overhanging the water.

Inside of Holborn Head is Scrabster Eoads. Many ships ride at anchor there

while the wind blows hard from the west. They are well protected by the

headland, which juts out towards the north-east. Scrabster Harbour is also

comparatively safe.

But when the wind blows from the north or northeast, the ships riding at

anchor there are in great danger. The waves come in with great force. They

come hissing along with their fleece of froth, and break with violent force

upon the shore. They rebound again, dragging the pebbles under them with a

rattle, and—to quote the words of Hardy—are like “a beast gnawing bones.”

After one of these storms, Dick went down to the sea-shore to ascertain

whether any of the secrets of Nature had been laid bare. “We have had a

terrible storm here,” he says; “such a force of wind that I have never felt

the like, so terribly strong and continuous. It has caused great disaster to

the shipping. The storm fairly whipped six vessels out of Scrabster Roads,

and dashed them ashore to ruin.

“When the wind abated, I went down to the shore, and found a piece of old

land strewed here and there with prostrate hazel stems. I picked out of the

clay five nuts. How long it is since they grew I know not, but it must have

been ages ago. Perhaps geologists would say that they grew when Britain

stood thirty feet higher than it does now. But that is all conjecture.

Certainly the land along our shores had once a very different appearance.”

On another occasion he says—“The wind to-day blows fearfully hard. A large

ship, with seventeen men on board, is ashore at Ham, thirteen miles off.

About mid-day we expected a ship ashore here. Unless the wind abates, I

should not be surprised if others came ashore to-morrow. The wind is howling

like mad, and roaring like thunder over the town.”

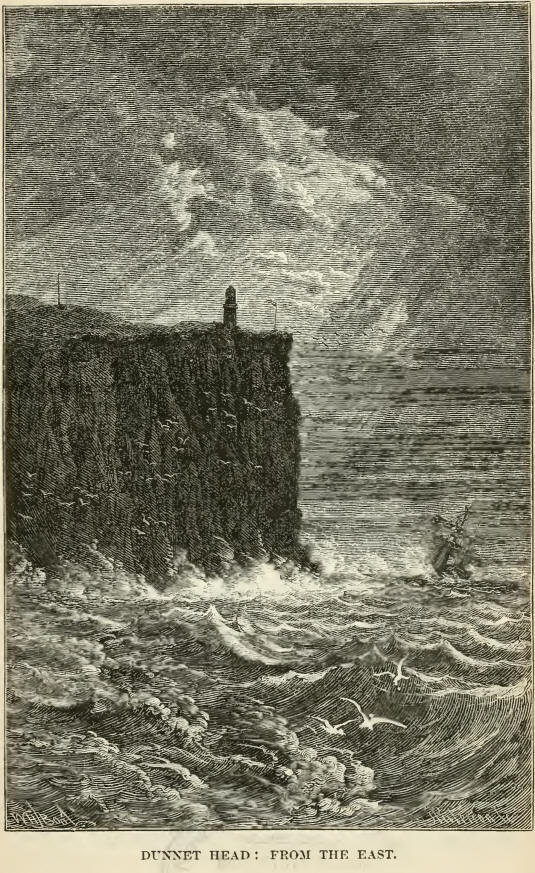

Dunnet Head, north-east of Thurso, was one of Dick’s favourite haunts. It

was a long walk to the lighthouse, which fronts the Pentland Firth. But he

often wandered to it, and descended the headland to the sea by paths known

only to himself.' The perpendicular rocks which surround the head, average

about two hundred feet high; but at the northern end, which forms the

northernmost point of Scotland, the rock rises three hundred feet above sea

level; and from the summit of the contiguous eminence, the height above the

sea is more than four hundred feet.

Dunnet Head forms a peninsula, extending from the village of Dunnet on the

south to the village of Brough on the north. From these points it extends

northward. The peninsula contains about three thousand acres of uncultivated

moor, with no fewer than ten small lochs or tarns on its summit. In winter

time the lochs are crowded with swans, geese, ducks, and northern seafowl.

Most of the birds summer in Greenland, and winter on Dunnet Head.

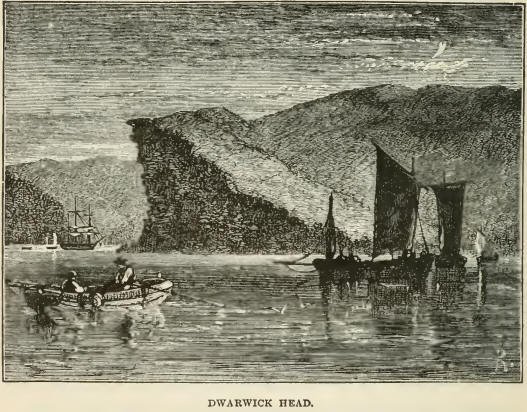

This immense rampart of rocky headland runs along the northern shore of

Dunnet Bay, by Dwarwick Head, in an easterly direction. Then turning sharp

round to the north by Rough Head, the rocks wend northwards, then slightly

eastwards, until you find yourself under Easter Head, where the lighthouse

is erected. This is the highest point of the cliffs. They then extend to the

south-east, and afterwards towards the south, ending at the village of

Brough.

In fine or even rough

weather, when the wind is easterly, a yachting trip under the cliffs is full

of interest. In Dunnet Bay the sea is quiet, being protected from the east

by the high grounds of the peninsula. Dwarwick Head forms a singular

headland, the strata dipping slightly towards the sea. Between this and

Rough Head is a wick or bay, in which ships find safe shelter —an old

retreat of the Vikingers.

Kough Head is a bold headland. Numerous boulders are strewn at the bottom of

the cliff. There are points near Dwarwick Head and Eough Head, where an

approach to the sands is possible, though, in some places, it is rather

precipitous. There are numerous gyoes along the headland, worn out into

inland caves by the powerful washings of the sea. There is one near Dwarwick

which penetrates far inland. When the sea is rough, and drives in from the

west, the sea dashes up far inland, and blows through the opening like a

whale, throwing abroad sheets of spray.

The precipices gradually rise. In certain places the rocks seem to have

slipped away towards the bottom, and left steep slopes overgrown by ferns.

There are numerous wild birds among the cliffs. Cormorants are seen winging

their solitary way towards the north. Deep caves appear in the face of the

rock; with here and there a recent slip from the summit to the sea, where

the stones lie in a rough slope. The red sandstone of the rocks looks so

clear, so solid, and so near at hand, that it might be thought they were

only a gunshot distant, though they are a mile and a quarter away.

And now we are under the lighthouse, where the strata are nearly level. The

precipice here is some three hundred feet high. The lighthouse is on the

crest of the rocks, only about thirty feet from the precipice. It is the

highest lighthouse in Scotland. The height of the lantern above the highest

spring tides is 346 feet, and the light is seen twenty-three miles off, on

either side of Dunnet Head.

Even here there seem to have been recent slips, for there are long slopes of

rock at the bottom overgrown with ferns and greenery. The sea is constantly

washing and grinding away the red sandstone and slates, so that, in course

of time, the lighthouse will have to be removed farther inland.

Notwithstanding the height of the cliffs, the sea, when driving strongly

from the west, rushes right up the face of the rocks, and dashes over the

lighthouse, sometimes breaking the glass with the stones which it carries

with it. Such is the prodigious force of the wind and the sea united, that

the very rock itself seems to tremble, while the lighthouse shakes from top

to bottom.

We are now in the Pentland Firth, and the waves are rolling strong from the

eastward. The wind and the waters dash about the little ship, and she tacks

and bears round under the shelter of the headland. But not before her decks

have been well drenched by the billows. She has now to make headway against

the tide, which is rushing into the Pentland Firth at the rate of some ten

miles an hour. At last, retracing her pathway under the rocks, Rough Head is

passed; a calm comes on; the ship makes a tack across the bay; and at length

Dwarwick Head is passed, and the buoyant little yacht makes her way into

Castletown harbour, from whence she set out.

We have thought it necessary to give this account of Dunnet Head, because it

was so often the scene of Robert Dick’s explorations. Sometimes also, Hugh

Miller accompanied him in his researches after the Old Eed Sandstone, which

is found on both sides of the headland. This will afterwards be found in the

course of the narrative.

In the course of one of his

letters to his sister, Dick thus describes one of his journeys to Dunnet

Head. It was made in April, while the weather was still very wild:—

“Determined not to he beat, I waited over snow, hail, frost, and rain, until

I could set out. Then I had my ramble. It was a fine morning, but after I

had set out it began to rain. It blew and rained for five miles. I saw

little beyond a hare country. The fields were red, and the grass by the

road-side was withered and brown. All was of a sad, desolate appearance. I

was walking in an easterly direction, and the wind was blowing south-west.

To fend me from the rain, I turned my face northerly, and saw only a tossing

sea, and the Orkney hills overspread with snow. I passed through the

mile-long village of Castletown, and there I saw trees, yes, most

respectable trees!

“On the top of a stone wall to the right I saw some tufts of moss. I went to

the moss and looked. It was all in fruit. I think it was Hypnum popuieum. I

had seen it before. I crossed burn after burn, and then the long dreary

sands of Dunnet lay before me—blank and bare, or tossed into fantastic

hillocks. The sand was blowing before the wind. The waves were thundering

along the shore.

“I saw a man breaking sandstone boulders. He little thought of what he was

doing, or of the time when ice went grinding along the surface of the stone

he was hammering. No: he was building a cottage, and the stone was only a

stone to him, and nothing more.

“Passing on, I left all human habitations behind, and had only heather,

heather, before me. The heather was brown and bumt-like, so severe had been

the weather during the past winter. As I passed on, I found a cocoon of the

Emperor Moth sticking on a piece of heather. I was next brought to a stop by

some crimson-tipped lichens—moss cups. They were taller than any specimens I

had seen before, but they were under shelter.

“After crossing another burn, and striding through heather only ankle deep,

I found myself on the edge of the precipitous cliffs of Dunnet Head. Before

I descended down their front I looked around. Orkney seemed quite near, with

the snow-wreaths on its hills. The waves of the Pentland Firth were rolling

away westerly.

“Down I went! down! It was at that place only about 100 feet deep. When I

reached the foot of the cliff, I gazed upward in wonder and admiration, full

of intense curiosity to see the various layers of sand—for such it once was.

It is not every day that one stands at the foot of such a cliff.

“I moved westwards. I passed along delighted. The scene was grand and

unusually striking. I came at length to a narrow fissure, up which I forced

my way in quest of Ferns. Yes, Ferns! Ferns grow green on Dunnet Cliffs all

the year round. In fact, Dunnet Head is a forest of ferns. It was the Sea

Spleenwort that I wanted, and sure enough I found it growing green in all

its glory. I gathered a few, and left the rest.

“Retracing my steps, I ascended the cliff. It then began to rain, and it

rained nearly all the way home.”

Dick often descended the cliff, sometimes to gather ferns, and at other

times to inspect the geological conditions of the rocks. One day he went

down the face of the headland a little to the west of the lighthouse. He

went searching about among the rocks and clefts, finding many new things to

wonder at. But he completely forgot the lapse of time. Looking round, he

found that the tide had risen and completely overflowed the path among the

rocks by which he had come. On one side was the precipice, on the other was

the sea, coming in higher and higher at every wave. He had no alternative

but to go onward, for the sands were still dry in front of him. At length he

discovered a portion of the headland which he thought might be attempted,

and he succeeded, with much difficulty and danger, in reaching the summit of

the cliff.

In fine weather, when the billows are asleep and the waters merely lave the

base of the cliffs, pleasure parties sometimes set sail from Thurso, and,

when the tide is low, they land on the sands under Dunnet Head. On one

occasion, Dr. Smith and a party who had just landed from their boat, found

to their amazement that Dick was there before them. He seemed to have got

there by miracle. But no ; he had merely come down the rocks by a path known

only to himself, for assuredly nobody else would have risked his life in so

perilous a descent.

Dr. Smith asked him to return with his party in the boat. Ho ! he would

ascend the rocks by the path down which he had come. Besides, he never

accepted any accommodation of this sort while on his journeys. His skin was

in a state of perspiration, which he desired to maintain. If he took a seat

in a boat or in a road conveyance, with his wet feet, he was sure to get

chilled, and the result was a severe cold. Hence he strode back to Thurso by

the heather, the sands, and the road, as he had come.

On one occasion Dick describes the geology of Dunnet Head. It is during the

month of June that he undertakes his journey. He has already reached Dunnet

sands, which are about seven miles by road from Thurso. The description is

best given in Dick’s own words:—

“Dunnet sands are a long and a weary trail in a warm day in June, when the

dark thunder-clouds creep overhead, when not a breath of air stirs, and all

is still and motionless, save the dull, sluggish fall, at solemn pauses, of

the incoming and retreating waves on the burning sands, or the humming of

the overjoyed flies feeding on the dead fish cast up by the tide; when the

cattle from tlie benty links have come down towards the sea, where they

stand knee-deep in it, stooping and eyeing it wistfully, but yet unable to

drink; when the parched sands stretch away in the distance, the heated air

flickering upwards like the breath of a furnace !

“I look up, and implore the ‘all-conquering sun to intermit his wrath.’ He

only continues to shine out stronger and fiercer; till at last, faint and

exhausted. I throw myself down, and drink out of the burn which flows across

the sands, careless of the consequences. Your very wise people may say what

they please about the consequences of imbibing cold water when overheated,

but I have never found any harm, but much good to be the result, and in no

case more than in taking this drink out of the burn as I crossed the sands

towards Dunnet.

“Refreshed and invigorated, I rose and pursued my way. Hot long after, I had

the pleasure of striking my first hearty blow on the yellow stones which

crop out through the unconsolidated beach. I examine and search for organic

remains. But no. Again and again my efforts are renewed, and still the

answer is, Ho.

“Passing on along the foot of the cliffs—now yellowish, then reddish—now

thin and slaty-like, then in thick solid beds—I go rambling along.

“Owre mony a weary ledge he

limpit,

An' aye the tither stane he thumpit; *

but thumped in vain. Oh for

one scale! But no; no organisms; not one, though you upturned the whole

stupendous accumulation of quartzy sand, which rears its lofty and weathered

front to the wasting waves and sea-breezes.

“We have chosen the right time, when the tide is at the lowest. Consequently

we are enabled to move along at the foot, of the cliffs, which otherwise

would be impassable. We actively and untiringly explore, but with no

success; and are at last so wearied that we clamber up to the top of the

headland by a rugged sort of footpath, and, moving along the edge of the

precipice, we make through the grass and heather for the crags immediately

facing the Western Ocean. How strange to find, as we move along, a white

butterfly or two flitting about, a solitary mason wasp, and a sparrow-hawk

looking out for prey, the sun all the while beating down upon us.

“It is possible to get down the western face of the rugged cliffs of Dunnet

Head. We got down, and what do we find? The sight is worth all the toil of

walking to see it. Immense masses of sandstone, fallen from the cliffs

overhead, skirt the mighty wall. The masses lie in rude confusion. Applying

the hammer to them, no remains of fish or quadruped are to be found, but

pieces of quartz, clay pebbles of a reddish brown, and in some places balls

of sulphur-yellow clay, as big as a man’s fist. Here and there are large

patches of something like rusty sheet-iron, which would almost make one

fancy that they were the remains of some Antediluvian Frying-pan that had

been swept to sea and buried there.

“There is very little real red sandstone at Dunnet Head. By far the greatest

bulk is what I take to be a yellow quartzose sand. In one place, and in one

place only, is the sand in any way red. In crossing Dunnet sands we had not

failed to notice little stones, standing out here and there in the sand,

left by the retiring tide, and great was my surprise to find the same

appearances here. In some places, where the boulders are a little asunder,

the exact beds of the strata are to be seen, walked over, handled, and

hammered. I had seen sandstone beds with here and there a pebble, but they

never struck my imagination so forcibly as now, when I was down upon my

knees and busied in the work of extraction.

“What a vast gathering of sand! I was forced to exclaim. Where did it all

come from? How long did it take to pile up this heap in the silent depths of

the sea? How long? How many years? These are pertinent questions,—questions

which enter one’s very soul. Then man feels instinctively his own

littleness, and his utter inadequacy to solve even the simplest of his

questionings.

“But however amazed he may feel at this vast pile of sand, it was at one

time unquestionably much greater. Looking across to the Orkneys, immediately

opposite, the spectator cannot fail to remark that they are of the same

material. Then, turning from the Orkneys to Hol-born Head, where a strong

sea now rolls, one cannot help looking back, and we are led to picture the

time when there was no sea between them, but only sandstone beds, stretching

continuously from shore to shore!

“The beds have been burst through by the ocean, and where dry land once was,

the grampus now rolls, and the tall ship speeds on her way to the farthest

ends of the earth. Amazing change!

“Art, empire, earth itself, to

change is doomed;

Earthquakes have raised to heaven the humble vale,

And gulphs the mountain’s mighty mass entombed;

And where the Atlantic rolled wide continents have bloomed.’

“Who told Beattie this? It

seems to prove Lyell's theory of the sameness of ancient and existing causes

for geological changes in the earth's surface. And the change is still going

on; and ‘ come it will, the day decreed by fate,' when not a vestige of the

sandstone of Dunnet Head will he found above the encroaching ocean.

“What induces me to think so is this :—1st, Dunnet Bay does not, in my

opinion, owe its existence to a fault, hut has been literally hammered out

by the force of the Atlantic waves. The sandy links are the broken remains,

in part, of the dispersed strata; and were they now to become solidified,

they would he found as rich in fossil remains as the present beds are

barren. 2d, The ocean tempests are telling surely on the western face of the

beds of Dunnet Head; and time alone is wanted to effect their ruin. 3d, The

beds on the south, at Brough, are in some places in a mouldering, crumbling

state, and the sea will ultimately effect a junction with the upper end of

Dunnet Bay. Dunnet Head will for some time be an island; but it will

ultimately be blotted out of existence altogether. There is a prophecy for

you!

“I remember once getting up, towards the end of harvest, while the blue

canopy above was still adorned and enriched with innumerable stars. I was

gaily crossing Dunnet sands in the first peep of day, when I made directly

across the peninsula for the stupendous cliff immediately westward of the

little haven of Brough. I found that the tide did not retire far from the

coast, but rose and fell close to the cliffs, wetting and allowing to •dry

the big stones at the base of the precipice.

“The cliff, under which I rested for a time, was about 150 feet high. It

seemed sound and hard. The morning sun rose in beauty. I hammered away, and

kept moving down upon the hamlet of Brough. There I found the cliffs in sad

decay; in fact, they were a sloping mass of rotten materials. A little out

to sea there is a ledge of what was once red sandstone. It is a mouldering

hint of what is to come. It is 50 feet in height, and rests upon slate.

“I had made this long journey in the hope of finding some very fine

organisms where the slate cropped out from beneath the sand. I found a few

fish scales and droppings, but no fossils; and sounded a retreat, very much

chagrined at having to return home almost empty-handed.

“There is a loch or two near Dunnet Head. There is one on the top of the

hill. It is a quiet secluded spot, a place of great attraction for wild

swans, geese, and ducks, during their autumnal migration, when winging their

way southward. There is another loch lower down, famed for its miraculous

cures. It is quite common for mothers to carry their sickly children there

on the first Monday morning of a Wraith; and, going round the puddle three

times, they dip in the chick at the end of each revolution. The children

have sometimes returned home cured. So they say.

“I remember a sort of cure. A poor woman took thither a child who could

neither sit, stand, walk, nor talk. She performed the customary observances,

and returned amidst much derision. But lo! a marked change took place in the

child. He gained strength, walked, and learned to speak. He often came to my

back premises, and called out: ‘Bakie, bakie, gie’s a lopiebut' still he was

very ancient-looking in the face. About two or three years after he died of

gravel. So that the cure, whatever it might be, was not permanent.”

The piece of water referred to by Dick is Dunnet Loch, or the Halie Loch,

not far from the village of Dunnet. It was once supposed to possess great

healing virtues. People came from all parts of Caithness and the Orkneys, to

be cured by the waters. The patient had to walk round the loch, or, if not

able to walk, he was carried round it. He washed his hands and feet in the

loch, and then threw a piece of money into it. He had to do this early in

the morning, and must be out of sight before sunrise. There was in ancient

times a Boman Catholic chapel dedicated to St. John at the east end of the

loch. Some say that the alleged healing virtues of the waters were converted

into a source of pecuniary emolument by tlie priests. The loch is merely a

collection of water dropped from the clouds, and possesses no healing or

other qualities, except those of rain water.

Among the superstitions of Caithness, the Swallow is called “Witch hag.”

They say that if a swallow flies under the arm of a person, it immediately

becomes paralysed. Is it because of the same superstition, that in some

parts of England the innocent Swift is called “the Devilin”?

|