|

“It is surely,” said Dick to

a friend, “a strange time we live in, when a poor devil cannot gather weeds

without being made a nine days’ wonder of to some, and a butt of derision to

others.”

Many people about Thurso, who saw Dick coming into the town with his feet

bedabbled with dirt and his jean trousers wet up to the knees, said that he

would have been much better employed in attending to his bakery than in

wandering about the country in search of beetles, bumbees, ferns, and wild

plants.

But he never missed attending to his business. Science was his pleasure; and

the pursuit of it became his habit. One science led to another. From Con-chology

he went to Entomology, and from these he went to Botany and Geology. Nothing

came amiss to him. He found “ sermons in stones, and good in everything.”

For a long time he kept all that he did to himself. He had no friends to

whom he could communicate the knowledge he had acquired. He was only a poor

baker. He did not mix with the educated class. He spent his thrifty savings

on books. His dress cost little. His best clothes were many years old. His

long swallow-tailed coat with brass buttons was considered antediluvian. His

tall chimney-pot hat was entirely out of date. Sometimes he was jeered at as

he passed along.

The boys knew that he had a love of nature. This is the first taste that a

country boy develops. Sometimes they were a little frightened at him. They

viewed him with awe, if not apprehension, when they encountered him among

the rocks with his hammer and chisel, or came upon him as he emerged from a

ditch, or from behind a turf wall, in his pursuit of insects, or grasses, or

mosses. But their fear was always tempered by the knowledge that any

curiosity they alighted on, in the shape of a stone, or a butterfly, or a

beetle, would always be repaid by the mysterious man when brought to him, by

a roll, or a cookie, or a biscuit, or sometimes by a sixpence.

One boy—now a well-known minister—called upon Dick when about twelve years

old. He was sent, with another boy, as a deputation from a number of their

schoolfellows, to ascertain something about the bones of a cuttle-fish which

they had found upon the shore. The boys went into his shop with considerable

fear; but they found the baker in excellent humour. He brought down from his

library several books, which he spread out among the loaves of bread on his

counter, and pointed out to them specimens of other cuttle-fish bones that

had been found. “We were much astonished,” says the minister, “to be told

that if we came back when he was less busy, he would tell us more about it;

but neither of us ever mustered courage for a second visit.”

Another says—“Boys out bird-nesting on the braes, or fishing by the

river-side or amongst the rocks, have often got from him a lesson in Natural

History which they would hardly forget in a lifetime.”

Dick began to be considered a general referee. When anything unusual was

found—a plant, a stone, a butterfly, or a fish—he was at once appealed to.

One day a boy came in with a message from a fisherman. A sun-fish had been

caught in Thurso Bay, and brought ashore. Dick was sent for to come and see

it. He was busy with his bread at the time, and could not leave the

bakehouse. The fisherman sent another message, saying that if Dick did not

come down immediately, he would cut up the fish. “Then tell him to cut

away,” said Dick; “I don’t like these peremptory orders.”

A person who made considerable pretensions to botanical knowledge met him

one day, and asked if he knew whether the county produced any Statice

armeria. “Oh!” said Dick, “if you will just call it Lea Gillyflower, or, if

you please, Thrift, you will find it at any roadside.”

Another gentleman found a pretty flower growing profusely in a small strath

a few miles out of Thurso. He took it to Dick. “Do you know that?” he asked.

“Yes,” he said; “you got it at the side of the burn at Olrig.” “How do you

know that ?” “ Because it grows in two or three more places in Caithness;

but these are too far off for you to have been there to-day.”

Another called upon him with a strange flower. “I have got a new thing for

you to-day, Mr. Dick!” “Oh no,” said Dick, “I know it quite well. You got it

near Shebster ”—indicating a small hillock on a moor in the western part of

the parish of Thurso. “Yes,” said the inquirer; “but how do you know that?”

“Simply because it grows nowhere else in Caithness.”

Thus, in course of time, he had pretty nearly mastered the botany of

Caithness. Among his other discoveries of plants in Caithness, which had

before been altogether unknown, was his discovery of the Hierochloe

borealis, or Northern Holy Grass, on the banks of the river Thurso. It is

called Holy Grass, because the people in Sweden and Norway were in the habit

of strewing their churches with it. It emits a scent when lying in

quantities, and when trampled on by the feet of the worshippers. It is

detected, when growing, by its beautiful spiral stem and its rich golden

seed.

The plant had been first admitted into the British Flora on the authority of

Don. But no one else had found it. After the death of Don the plant was

placed in the doubtful list of the London Catalogue, and it was finally

dropped out altogether. Dick was surprised at the discovery, but he took no

means to make it known. He kept the plant for about twenty long years beside

him. He was too solitary and too bashful to rush into print with his

botanical findings. It was only when a young botanist, who had heard of Mr.

Dick’s scientific knowledge, called upon him, saw the plant and ascertained

its habitat, that the information about the new plant was communicated to

the Professor of Botany at Edinburgh.

The professor at first doubted the existence of the plant in Britain. He

could scarcely believe that it existed in Caithness, the northernmost county

of Scotland. He observed, however, that if Dick had really found the plant,

he had rescued the celebrated botanist Don from an undeserved calumny. For

Don had asserted that the plant was found in Britain, whereas all the

botanists of note averred that the Holy Grass was not indigenous, but had

been imported from other countries.

Dick was specially requested to send a communication respecting the plant,

and where it was to be found. He accordingly did so in July 1854. He also

sent a specimen of the Holy Grass to Professor Balfour of Edinburgh. We must

here anticipate; and insert the paper which Dick prepared for the Botanical

Society, twenty years after the plant had been found. The paper runs as

follows :—

“About ten minutes’ walk from the town of Thurso there is, by the

river-side, a farm-house known by the name of the Bleachfield, opposite to

which, on the eastern bank of the river, there is a precipitous section of

boulder clay; opposite to the clay cliff, and fringing the edge of the

stream. Any botanist can, in the last week of the month of May, or in the

first and second weeks of June, gather 50 or 100 specimens of Hierochloe

borealis. Passing upwards along the river bank, and at no great distance,

there is another clay cliff, where a few hundreds of Hierochloe may likewise

be got. It also fringes the edge of the river. But the plant must be looked

for at the time indicated; for by the third week of June the beauty of

Hierochloe has passed away, and by the first of July the herbage has become

so rank that the Holy Grass, now ripe, and turned of a silky brown, and is

completely hidden from view. Farther up, between Giese and a section of

boulder clay a little below Todholes, the plant may likewise be picked in

hundreds. Hierochloe has never failed to appear in these localities during

the last twenty years.”

The Royal Botanical Society afterwards sent Dick a special vote of thanks

for his paper, and also for the specimen of the plant which he had sent for

the Botanical Gardens.

To return to his botanical wanderings. His sister, who lived at Haddington,

was very delicate, and he often tried to amuse her with the descriptions of

his walks in the country.

In the beginning of July he writes to her as follows : —“I have had two

walks—one of five miles, the other of ten miles. The five miles’ walk was to

see a fern called the Moonwort. It grows in abundance in a spot not far

away. I shall never forget the strange wonder with which I first saw it. So

I again walked off to the locality, where I knew it grew in all its glory.

The season has been very dry here, and the fern has not attained its usual

height. Nevertheless I found it. During my journey I saw much to admire.

“My ten miles’ walk I had yesterday evening. It was fearfully warm. The sky

was full of fire, hut it did not rain. There were great black mountains of

clouds in the air. It was a dead calm, with not a breath of air. I was told

that I must not go out, for it would he a downpour before long. But ‘he that

will to Cupar maun to Cupar.’ My imagination told me of beautiful geraniums

(Storksbill), which I longed to see. Off I went I The clouds were in motion,

but without wind. It was terribly sultry. After a long perspiring walk I

arrived at my journey’s end—a small precipice, lined with plants.

“I was now at home—intensely at home. The precipice was not in length a

stone’s throw. It was only about twenty feet in height. But there I found

many most interesting plants. There were a few of the Trembling Poplar

trees, about four, feet high. There were Roses and Willow Herb in flower (Epilobium

angustifolium, E. montanum, and E. quadrangulum). There was Arabis hirsuta,

a plant I never get in Caithness but here: Stone Bramble, Common Sanicle,

Carices, and Butterworts in scores. And in the crevices of the crags

ferns—Male ferns and Lady fems—Black Spleenworts, Maiden-hair Spleenworts,

and many other plants. Among the rest I found plenty of Bough Brome Grass—a

grass I saw alive for the first time—alive by scores. So here was my reward!

Well, I am increasing in knowledge, if not in wisdom. I hope to get up at

one o’clock tomorrow morning.”

A little later in the month he says—“This being one of my rambling days I

did not leave Thurso until the postman had gone round with his letters

between one and two o’clock. Of course I could not go far to-day. But there

is a fern growing about a mile and a half off, which I should like to see

once more. I once thought the fern to be very rare, not having met with it

in all my rambles, except at the foot of the hill of Morven, in the extreme

south of the county. Then I found the same fern about four or five miles

from this, eastward of the Fairies’ Hill (Lysa); afterwards about a mile and

a half out of Thurso ; and then about three-quarters of a mile eastward of

the town. The search for plants is amusing; and when I come unexpectedly

upon plants in a spot which I had before minutely searched, I wonder where

my eyes had been all the time.” .

“On Saturday last,” he says in another letter to his sister, “I got up in

the morning at three, worked until midday, and then I set off on a journey

of nine miles to gather a specimen of a plant. Before I started I took off

my shoes and dipped my feet, stockings and all, into a basin of water. I

then tied my shoes on and set off. When I had gone six miles I came to a

burn ‘ roarin’ fou,’ through which I walked ankle-deep. Fifteen minutes

later I walked through another burn, and then through another and another

burn—four burns in all.

“I pulled the plant and returned homewards. My route lay across Dunnet

sands. The tide was ebbing. I kept close by the waves. As they rolled in, in

long breakers, they went far up the sands. For about three-quarters of an

hour I walked ankle-deep in salt water.

After leaving the shore I had

six miles to walk. I reached home at eight in the evening with my plant,

having walked eighteen miles in four hours and forty minutes.”

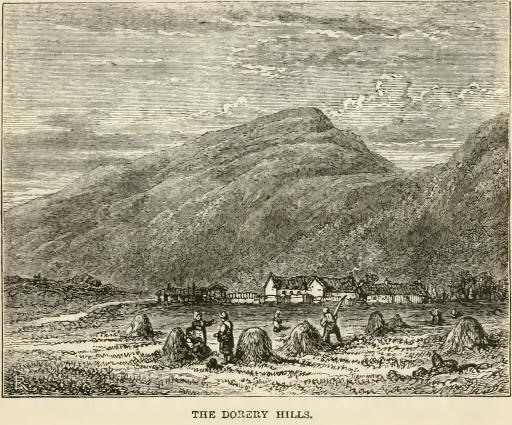

On another afternoon in July he goes to the Dorery hills. “I had a ramble,”

he said, “on Saturday last, after my day’s work was over. While on my way I

found in a quarry, at a loch, a fossil fish snout or two, and some plants. I

got to the hills, about ten miles off, and examined ferns and roses. I had a

grand view of the Sutherland hills. I stood in a sheltered nook, and gazed

at the sunlight shining far over the distant mountains. I never forget any

of these moments. I turned aside this morning just to gaze upon the moon. It

was about two o’clock in the morning. All was still, solemn, and

impressive.”

The road to the Dorery hills lies through a hare and slightly undulating

country. The fields are separated from the road by fences of Caithness flag.

On either side you observe here and there mounds of green earth, underneath

which are said to be the so-called Picts’ Houses. After the cultivated

fields, come the moors —quiet, solitary, and sublime.

After the moors you reach the heathery hills. The highest of the hills is

called Ben Dorery. There is a cleft between the two principal hills, and at

the farther side of the main hill is a hollow, surrounded by projections of

slaty rock, in which Dick would sit down, and look with delight on the

prospect before him. In the far-reaching plain below there was nothing but

heather moor, and moss, in the midst of which twelve lochs might be seen

glittering in the sunshine, with the Sutherland hills far in the distance.

The scene is lonely and solitary. Not a house is to he seen. Not a sound is

to be heard, excepting the shot of a sportsman during the grouse season.

Below the hill, is Loch Shurery, quietly sleeping in the sunshine.

Rising the hill and looking north, you see the flat county of Caithness,

with moors and lochs in the foreground, and beyond them the flag-fenced

fields in the distance. The Dorery hills were attractive to Dick, not only

because of the solitary scenery, but because they were full of ferns of many

sorts, togetliei with many of the plants and grasses of which he was

constantly in search.

Dick liad another special fernery at Achavaristil; under the Reay hills,

about ten miles from Thurso. It was nearly opposite Sir Robert Sinclair’s

shooting-lodge. It was a sheltered place, where ferns grew in beauty. Dick

kept the place an entire secret. For a long time, no one obtained access to

it. Ho one knew of it. He transplanted ferns from all parts of the county,

that they might grow and spread there long after he was dead. But alas, some

mischievous person found out the place, and pulled up the “weeds.” What a

hitter day that was for Robert Dick! |