|

Robert Dick proceeded with

his study of natural science. From conchology he went on to entomology and

botany. He gathered insects while he collected plants. They both lay in the

same beat. After his bread was baked in the morning and ready for sale, he

left the shop to the care of his housekeeper, and went out upon a search.

Or, he would take a journey to the moors and mountains, and return home at

night to prepare for the next day’s baking.

He began to make his entomological collection about the year 1836, when he

was about twenty-five years old. He worked so hard at the subject, and made

so many excursions through the country, that in about nine months he had

collected nearly all the insect tribes that Caithness contained. He spent

nearly every moment that he could spare until he thought he had exhausted

the field.

He worked out the subject from his own personal observation. He was one of

those men who would not take anything for granted. Books were an essential

end; but his knowledge was not founded on books, but on Nature. He must

inquire, search, and observe for himself. He was not satisfied with the

observations of others. He must get at the actual facts. He must himself

verify everything stated in books.

He was not satisfied with the common opinion as to the species or genus to

which any individual of the insect world belonged. He tested and tried

everything by the touchstone of science and careful observation. If he had

any doubts about an insect, from a gnat to a dragon-fly, he would search out

the grub, watch the process of its development from the larva and chrysalis

state, until the fly emerged before him in unquestionable identity. It will

thus be observed that he was from the first imbued with the true scientific

animus; and in the same spirit he continued to find out and discover the

true workings of Nature.

The Thurso people did not quite understand the proceedings of their young

baker. He made good bread, and his biscuits were the best in the town. But

he was sometimes seen coming back from the country bespattered with

mud,—perhaps after a forty or fifty miles’ journey on the moors in search of

specimens. What were they to make of this extraordinary conduct ? It could

have no connection with baking. What could he have been doing during these

long journeys ?

He was now doing fairly in business. He was not yet distracted by the

competition that afterwards ruined him. His wants were very small. He had

only himself and his housekeeper to provide for. He was accordingly able to

save money, and with his surplus capital he bought books.

“How painfully, how slowly,” he once said in a letter to Hugh Miller, “ man

accumulates knowledge! How easily, how quickly, it escapes and is gone!

Blessings on the noble art of printing, under the shadow of whose dominion,

thoughts, words, and deeds, are piled up like the proliferous corn of old in

the storehouses of Pharaoh! ”

Dick was now buying his flour from a merchant in Leith. He requests the

merchant to send him hooks as well as flour. The books were purchased,

packed in paper in the centre of the bags, and despatched to Thurso, by way

of Aberdeen, Wick, and the Pentland Firth. We find him thus receiving the

Gardener's Dictionary, the Naturalist's Magazine, and the Flori-graphia

Britannica. He also directs the flour merchant to buy him a microscope, and

to send it him as soon as possible. His correspondent says, “I have at

length bought for you the long-wished-for microscope. It is a very powerful

one. I hope you will find yourself amply rewarded for your time and

expense.” The microscope was despatched in July 1835, and it reached Dick in

safety. He found that, in the course of his investigations into the minutiae

of objects, he could not do without the microscope.

The flour merchant afterwards sent Dick numerous volumes of the Naturalist's

Library, and bought for him a copy of Hogarth’s Works,—the large edition,

with the original plates restored. We find, from the bill of lading

accompanying the flour and the volume, that its oinding cost Dick two

guineas. Other books, relating principally to botany, conchology, and

geology, shortly followed. Sometimes a phrenological cast from O’Neil was

imbedded in the flour. We find, from the communications that passed between

the correspondents, that Dick paid his accounts promptly,—usually within a

fortnight after the delivery of the flour.

When the books arrived at Thurso, and were unearthed from the flour, Dick

set to work and devoured them. For Dick was a great reader, almost a

ferocious reader. He read everything about air, earth, sea, and heaven, as

the multitude of books collected by him sufficiently indicate. He had plenty

of leisure. When his bread was baked, and ready for sale, he had nothing

else to do for the day but read and wander. When the weather was wet and

stormy, as it often was, he read, drew, and wrote letters to far-away

friends. For he had many correspondents, as the following pages will show.

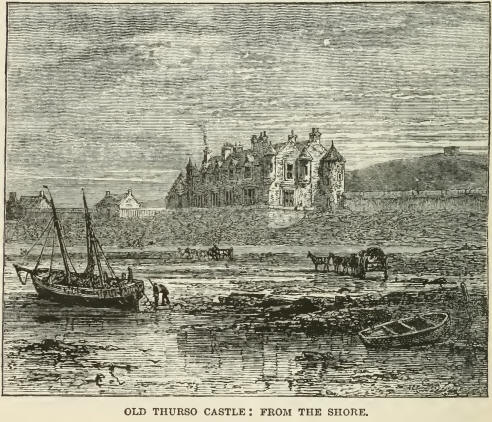

When the weather was fine, he

set out on his walks, along the shore, or up the country, sometimes as far

as Morven. “Many is the walk,” says one of his old acquaintances, “ which I

have enjoyed in his company on the sea-beach near Thurso Castle. I was once

with him, when I found a new shell, and it was truly delightful to hear him

explain its history and habits, as if it had been his next-door neighbour,

and he had known the tiny thing all his life long. How kindly and meekly he

spoke, and how ready he was for a joke; and what a keen perception he had of

the ridiculous in everything that crossed his observation. The same night we

also found a curious sort of nut, which he told me had been carried by the

ocean currents and prevailing winds all the way from the West Indies, and

was cast up on the beach just below Thurso Castle.”

“On another occasion,” says the same writer, “I walked with him on a

botanical excursion, as far as I could, up the Thurso river; and I am not

far from the truth when I say that he talked all the way. "I begin slowly"

he said, referring to Iris walking, ‘but we’ll improve before long/ and so

it proved; for before he had reached Oldfield he had got into a

four-miles-an-hour pace, and by the time we reached Isauld it was a regular

trot and race down the banks and across the river to one of his favourite

haunts. I cannot now remember what were the special prizes of the excursion,

though I well remember that we came home richly loaded with things, to me

rich and rare, which, with his usual kindness, he named and labelled for me

next day. After a lapse of more than sixteen years, I lighted accidentally

one day on a pile of plants, collected principally in Caithness, and forming

my first herbarium. It had passed through the hands of Mr. Dick, and bears

his sign-manual on every sheet. Any one would say it is the handwriting of

an educated man—a bold, full, fluent hand—without any trace of the

crampedness and angularity of those who earn their bread by manual toil.

Besides, the technical names of the plants are always spelt correctly.”

But it was very seldom that he made his botanical excursions with others. He

almost invariably went alone. When he had arranged his work, and had a

journey in view, he had everything in order by the hour that he intended to

set out; and then nothing would detain him. When about to start on a long

journey, he wore thick-soled boots, with hob-nails in them. He soaked his

stockings with water; and when he came to a burn he soaked them again. He

took with him some ship biscuit, which was easily carried. This constituted

his principal refreshment during his long journeys. The burn or the mountain

tarn supplied beverage enough for one of the most temperate and enduring of

men. “I never drink much when travelling,” he used to say. “It takes the

wind out of me, and seriously interferes with my comfoit and endurance.”

How he delighted in spring! He welcomed its approach with joy. The winters

were usually cold and stormy. The cold winds blew violently over Caithness,

and prevented any green thing appearing on the surface. But Dick was up

before the sun was up. He was out before the flowers were out. He watched

them thrusting their way upwards into the air, watched them while they

blossomed into flowers, and watched them while they shrank into decay.

Spring is late in the north. Even at the beginning of May the earth is still

brown. Only in some sheltered spots by the river-side are any green things

to be seen. There are very few hedges near Thurso. “On the 4th of May,” says

Dick, “the buds are only swelling. There is no 'May blossom’ in Caithness.

Even at the end of May the few hedges are not in full leaf.” The first

flowers that appear are the yellow Coltsfoot, the yellow Primrose, the

yellow Buttercup, the Marsh Marigold, the little yellow Celandine, and a few

blue flowers of the Dog Violet. These are all the beauties of the northern

flora in May. The cold winds are still sweeping over the county.

Dick went out one morning at the end of May, towards the Beay hills, to see

how the flowers were growing. The morning was cold and cheerless. The flag

fences along the road were hung with rain pearls. When he reached the Beay

links, he found the ground covered with cowslips. From thence he went up the

hills to the waterfall to gather ferns. They were only beginning to expand.

The summer moss, Polytrichum was there in thousands. By and by everything

would be in bloom.

Even on the 24th of June—midsummer day— the ferns were not fully out. “The

first fern I saw,” says Dick, “was Lastrea dilatata, but it was so ugly that

it was not worth looking at a second time. The next I saw was Asplenium

trichomanes, or Common Maiden Hair; but the specimens were too small for my

purpose. The next was the Black-stalked Spleenwort. I passed through a

forest of brackens, and saw the Northern Hard Eem, and the Black Bog-rush—a

plant rare in Scotland, even on the west coast. I passed on and went

up-hill, where I saw the Beech Fern and many other plants, of which European

Sanicle was the most abundant. It was once thought to cure every disease,

and was called ‘Self-heal.’ I saw the Common Polypody, and the Oak Polypody.

Up the hill the Foxglove was the most conspicuous. I also found Woodruff,

Spottedleaved Hawkweed, and Persian Willow; white roses and red roses; and

other plants too numerous to mention, I wound along by a sheep-road to the

hill-top, and lay down, looking across the dead level of the county. I

counted thirteen lochs! ”

At the beginning of July, he adds,—“We are just getting into first-rate

order here as to wild plants. We shall by and by have a grand display of

yellow flowers —all yellow; tens of thousands, and ten times ten,— all

destined to pass away after fulfilling the great end for which they came

into flower—leaving seed for times to come times without end.”

On the 24th of July he says, “Now it gets warmer. The com becomes half full

of marigold. The heather begins to bloom. I made for the seaside,” he adds,

“and found a butterfly sleeping on the heather! Poor thing!” As the summer

heat increases, the Caithness grasses, plants, and flowers, make their

appearance in succession. “People in the south,” says Dick, “think that as

Caithness is so far north, its flora must differ greatly from that in their

own neighbourhood. No doubt the general aspect of a district in the south

differs very strikingly in its prominent features. And yet, after all, we

have very few plants that may not also be found in the south.

“The Caithness flora is not alpine—not even sub-alpine. I know of only three

Baltic plants in Caithness ; and of these only one is a rarity. Indeed it is

peculiar to Caithness; for Caithness is the only British district in which

it grows. We have the Baltic rush by the river-side. But then Juncus

balticus grows at Barry Sands, near Dundee. Last summer, I was much pleased

to meet the Baltic rush growing in a small marsh about six miles inland. I

was highly delighted. I had never seen it so far from the sea.”

Robert Dick proceeded with the study of botany in the most resolute way. He

would take nothing for granted. Where others had observed, he also would

observe, and verify for himself. Hence, with the utmost toil and labour, he

wandered over Caithness, to see the plants growing in their native habitats.

He must find them where they grew, and study them, from time to time, on the

spot. He determined to master the entire subject. He mapped out the country

into districts, and resolved carefully to examine each of them in turn. It

was a long and arduous work, but he successfully carried out his purpose. At

length the plants of Caithness, from one end of the county to the other

—from the Morven hills in the south to Dunnet Head in the north—from Noss

Head in the east to Halladale Head in the west—became as familiar to him as

the faces of familiar friends.

The banks of the river Thurso were among his favourite haunts. He searched

the valley in its remotest nooks,— from its source in Bencheilt to its

entrance into the sea at Thurso. The flats along its serpentine course

abound in plants and grasses, which he scanned with the true naturalist’s

eye. During the long summer nights, when “day never darkens into mirk,” he

would make journeys of forty or fifty miles, for the purpose of gathering

some favourite plant in its far-off native habitat. He would return home in

glory, bringing with him a stem of grass, a flower, or a bulb.

During midsummer time in the north, it is light nearly all the night

through. The sun slightly descends below the horizon, but the light still

remains. Farther north, the sun is seen at midnight. When it rises in

Caithness, the morning is a prolonged dawn. An eloquent writer says, “ The

earth is most beautiful at dawn; but so very few people see it, and the few

that do are almost all of them labourers, whose eyes have no sight for that

wonderful peace, and coolness, and unspeakable sense of rest and hope which

lie like a blessing on the land. I think if people oftener saw the break of

day they would vow oftener to keep that dawning day holy and would not so

often let its fair hours drift away with nothing done that were not best

left undone.”

Dick had many a long and lonely walk at sunset, at dawn, and even at

midnight. And yet he was not lonely. His love of nature made a paradise of

that bare north country.- His solitude was not loneliness. Solitude, to him,

was sweet society. He felt the companionship of nature about him—on the

moors, in the mountains, and along the sea-shore. On calm evenings, when the

sea was at rest, he walked along the sands. The sea, though quiet, seemed to

breathe. It was like a living thing— like a creature at rest.

Dick was an insatiable wanderer. When he had done his daily work, and the

weather was fine, he set out on his botanical excursions. The county was all

before him. He would go to the Eeay hills in search of ferns; or up the

Thurso river in search of plants and grasses; or to the extreme point of

Dunnet Head. His eyes were always open to receive new impressions. He

wondered at the infinite varieties of nature, even in that cold bare

country. The lines written by Longfellow upon another great lover of nature,

are quite as applicable to Dick:

“And he wandered away and away

With Nature, the dear old nurse,

Who sang to him night and day

The rhymes of the universe.

“And whenever the way seemed long,

Or his heart began to fail,

She would sing a more wonderful song,

Or tell a more marvellous tale.”

He was more joyful on the

moors than amid the noise of streets. There he was alone with himself. Hot a

sound was to he heard as he trudged along, save the heating of his own

heart—not a voice save that of heaven. The clouds threw their purple •

shadows over the moor. The grouse flew up with a whirr, whirr! The blue

mountain hare flew past him, though there was no danger to be apprehended

from him.

The deluge sometimes caught him. One afternoon, in August, he walked

thirty-two miles amidst soaking rain. He had gone up to the top of a

mountain, and found only a plant of white heather. He walked and ran all the

way hack, through moors, mosses, and heather, jumping the flagstone fences;

and at last reached home after nine and a half hours’ walking and running.

Yet he was up next morning at six, and went through his day’s work as usual.

The following is a pleasanter day’s adventure. It was written to his sister

at the end of August:—“ Since I wrote you last, I have managed to walk

thirty-six miles. Long, long ago, I chanced to find a Fern eighteen miles up

the country. It was not new, consequently not a discovery; hut it was as

good as such to me. It had never crossed me in all my wanderings, or rather

I had never found it until then. Ho one told me where it grew, for the best

of reasons—that no one knew.

Since I first found it, I have every year gone a-walking to it, just to

visit it, again and again. This year, I have been there and back. The fern

is very small: I enclose a specimen. It is the Eue-leaved, or Wall

Spleenwort. The rocky spot in which it grows contains many other ferns, some

of them not at all common.

“Besides the wild rocky scenery of the place, there is the only approach to

a Highland glen which we have in Caithness. You set out from Thurso, and for

the first three or four miles there is nothing hut corn and here on each

side of the road; and in dry leas, showers of yellow Crowfoots and Ragworts;

with here and there the blue heads of Scabious, or yellow Dandelions, 01

yellow Hawkbits. All is yellow, yellow, dashed here and there with masses of

purple heath, redder by far than you can possibly imagine.

“On you go, diverting the time as you best can,—for all is wonderful. Then,

at the distance of ten miles from Thurso, you are on a hill-top, and you

stand and look around you. It is sweet to stand on a hill-top, and gaze far

up the country. Southwards you see farther than you will ever wander. Of

course you cannot tell in words all that you see. You gaze eastward,

northward, and westward; and then, after satiating yourself with the

prospect, you move down the farther side of the hill, and get onward. Twelve

miles, thirteen miles, and many wonders are to be seen. And in due time you

get among the heather—heather everywhere—and water black to drink. After

going a mile through a moor, you find yourself all at once on the brink of a

precipice. You look down, and the waters are tumbling and surging below; you

are satisfied, and could sing with joy too. After a time, I went my way

homewards.”

Dick often relieved his solitary moments by writing to his sister, then

living at Haddington. She had complained to him of her lowness of spirits,

when he thus wrote:—“Cheer up, cheer up, my bonnie sister, and I will tell

you a story. One fine summer evening, not long ago, your brother set out for

the far-away hills. He had been there before. The sun’s heat was strong when

he set out (it was then August), but on he went, past bothies, and houses,

and milestones, until he was ‘o’er the muir amang the heather.’ Then past

burns and lochs, up a hill and over a hill, through a bog and through a

mire, until the sun set, and still he was toiling on, with a long, long moor

before him.

“Have you ever been all alone on a dreary moor, when the shadows of the

coming darkness are settling down, and the cold clammy fog goes creeping up

the hill before you? It is hard work and very uncanny walking to pick your

steps, as there is no proper light to guide you. Tor you must remember that

moors are not bowling-greens or finely-smoothed lawns. They may be flowery

paths, it is true, but very rough ones, full of man-traps, jags, and holes,

into which, if you once get, you may with difficulty wade your way out

again.

“But on I went,—hop, step, and, jump,—now up, now down, huffing and puffing,

with my heart rapping against my breast like the clapper of a mill. Then

everything around looked so queer and so quiet, with the mist growing so

thick that it was difficult to distinguish one hill from another. Had I not

been intimately acquainted with every knowe and hillock of the country

through which I was travelling, I never could have got through it. But,

cheer up ! never lose heart! There’s the little loch at last, and there’s

the hill! Ay, hut your work’s not done yet. You must climb the hill, for

what you seek is only upon its very top.

“It’s rough work running through a moor, hut it takes your wind clean out of

you to climb the hill that lies beyond it. Were you ever up a hill-top at

night, your lee lane, with the mist swooping about you and drooking your

whiskers and eyebrows? I daresay no. But up this hill I had to clamber on my

hands and knees to find the plants that I had come in search of. Yes! I

found them, though I was not quite sure until the sun had risen to enlighten

me. Then I found that I had made out my point.

“The light enabled me to make my way downhill. Feeling thirsty, as well I

might, I clambered over rocks, and braes, and heather, to a very pretty loch

at the hill-foot. Picking my steps to a place full of large stones, I came

to a pair of them where I stooped down into the clear water and drank my

fill. It is a grand thing to dip your nose down into the water like a bird,

with the shingle and gravel lying below you, and then take your early

morning drink.

“But I have no time to say out my say. Only this, sister, only this : never

lose heart in the thickest mists you should ever get into; but take heart,

for assuredly the sun will rise again, and roll them up and away, to be seen

no more.”

In a future letter to his sister, written on the 12th of November, he thus

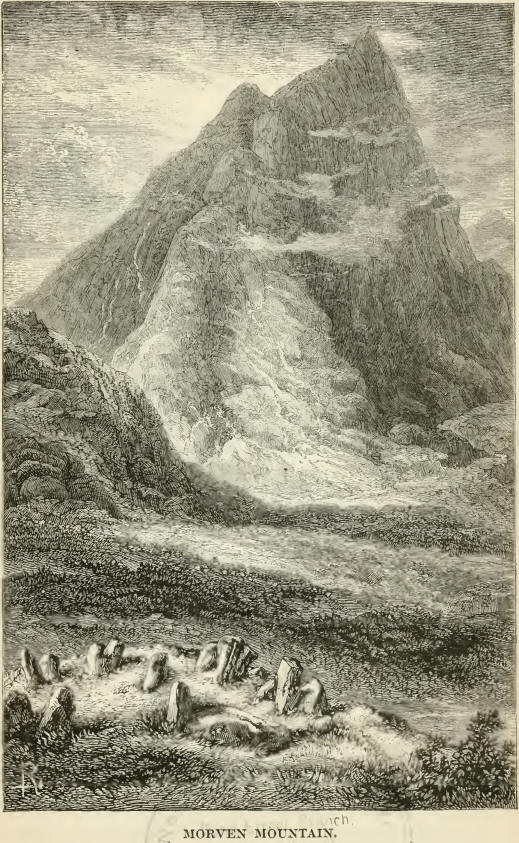

describes his journey to Morven top :—

“On Tuesday last I set out at two o’clock in the morning to go to the top of

Morven. Morven is a hill to the south of this, and by measurement on the map

28 miles as the crow flies. But taking into account the windings and

turnings of the road—up hill, down hill, and along valleys—it is a good deal

more : say 32 miles from Thurso to Morven top.

“For the first 18 miles I had a road: the rest of the way was round lochs,

across burns, through mires and marshes, horrid bogs, and hummocky heaths. I

tucked up my trousers, and felt quite at ease, though I was ankle deep, and

often deeper, for fifteen minutes on end, and sometimes more. When I had a

marsh to wade I had it level, but when I had heather I had an awful amount

of jumping. ... At last, however, I found myself on the top of the famous

Morven.

“The Caithness people have few hills. They think a mighty deal of Morven and

Maiden Pap and Skerry Ben. But these hills are not much to boast of. They

are none of them as big as books make them, and I laughed when I thought of

what people had said to me about this wonderful Morven. One said that it was

so very high that it would take half a day to climb from the foot of the

hill to the top. Another account, given in a book, stated that Morven could

only be ascended from the west side, being totally inaccessible on all other

sides. Downright nonsense! Morven is accessible on every side.

“My object in ascending the hill was to gather plants, and of course I went

up the steepest face to get among the crags and stones near the top. Morven

is poor in plants. I found nothing new. True, the season was too far gone,

but there in sheltered spots many of them still lived. On the top Alchemilla

aljpina was in flower. I observed from the decayed leaves on all sides that

the various species were not many. Braalnabin, a much lower hill, and much

nearer to Thurso, is better for ferns. Two weeks since I went there and got

nine different ferns all in bloom, though none of them were new to me.

“Strange it was to look around me. The day was cold and stormy. The sun was

shining above me, but a snowstorm was battling far below. Skerry Ben was

grey-white with snow. The sound of the wind among the crags was like the

roaring of the sea along the shore.

“I reached Morven top at eleven o’clock A.M. and left it at two p.m. It was

now mid-day. The river of Berridale runs at the foot of Morven. The best way

of getting over it is to wade through it; but what of that? The Highlandman

walks best when his feet are wet, and so does the Lowlandman, if he could

only be persuaded to try. In going to Morven I had waded no fewer than six

burns, and at least a score of marshes. My feet had not been dry since seven

in the morning.

It was all the same to me

which way I took. ‘Onward !’ was the word. And yet the light of day was gone

and the moon was up, long long before I gained a civilised road.

“The night became windy and stormy. Tremendous sheets of hailstones and rain

impeded my progress, so much so that I thought, as Burns says, that ‘ the

deil had business on his hand,’ and that he was determined to finish my

course with Morven. But no! In spite of hail, rain, wind, and fire (in fact

I had them all), I got home at three o’clock on Wednesday morning, having

walked, with little halt, for about twenty-four hours. I went to bed, slept

till seven o’clock, then rose, and went to my work as usual. Sixty miles is

a good walk to look at a hill. Oh, those plants, those weary plants!”

On one of his midnight excursions Dick was taken for a poacher. It may be

mentioned that the river Thurso is one of the best salmon rivers in

Scotland, Indeed, in early spring, there is no river that comes up to it.

Sir John Sinclair boasted that on one occasion 2500 salmon had been caught

at one haul—a draught that has never been exceeded. The price paid by the

salmon-fishers is so high—at present £20 per rod monthly— that the river is

carefully watched to prevent poaching.

One night a gentleman in charge of the river went out to see that the

keepers were doing their duty, and also to detect the poachers if he could.

He went to a particular spot where there were evident traces of poaching.

The river was then in good poaching order.

Just at the break of day, an hour or more before sunrise, the watcher saw

the figure of a man on the horizon, some hundred yards distant. He shrank

down, and crept forward, watching the man's movements in the grey dawn of

morn. He was seen close by the river’s side, prowling up and down the banks.

Surely this must be a poacher. The man moved on. When he appeared on some

high bank, the watcher hid himself so that he might not be seen between him

and the horizon. He crawled forward on all fours, stalking the poacher as he

would a deer.

At last, after nearly two hours’ stalking and dodging, the man suddenly

disappeared in some low crevices in the rocks, just below Dirlot Bridge. The

sun was just rising; the watcher saw him crouching down, as if hiding

something amongst the ferns. Of course it must be a salmon! With beating

heart, he suddenly rushed up to the man, and shouted, “Now I have caught you

poaching!”

The man’s back was towards him. He was intently gazing on some object before

him. He turned round in a composed manner, and said, “No, sir, I am not

poaching; I am only gathering some specimens of plants!” He then opened his

handkerchief, which contained some herbs, plants, and flowers. The watcher

was disappointed and disgusted. He had been crawling for two hours on his

hands and knees, coming up with his man, and finding in his possession, not

a salmon, but a lot of things which, in his estimation, were worse than

useless!

Dick was then sixteen miles from Thurso. He had left home at midnight in

search of his favourite botanical specimens. Some of them were so minute and

delicate that they could only he seen at sun-dawn. It was only at the break

of day that they unfolded their delicate tints, spread their leaves, and put

forth their lovely blossoms to the rising sun—perhaps revealed to the

per-fervid botanist by the glistening of a dew-drop.

Thus Dick was rewarded, but not the salmon-watcher who had stalked him. |