|

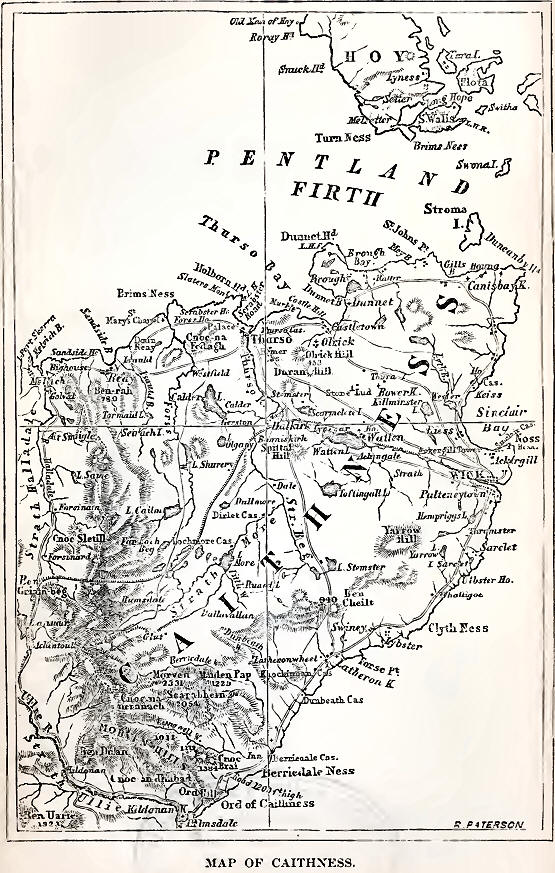

The name of Caithness is

derived from the old Norse. It indicates the ness, naze, or nose of Cattey.

Many of the headlands are also denominated ness, from Brim’s Ness to the

west of Thurso, to Noss Head north of Wick. Indeed, the same word is applied

to headlands along the east coast of Scotland and England—from Tarbat Ness

in Boss to Dungeness in Kent. The same word is applied to the Naze in Norway

and in Essex, and to Cape Gris Nez (Gray Nose) near Calais. It usually

indicates a headland which the Scandinavians have named, or near which they

have settled.

Caithness seems to have been

almost entirely Scandinavian. The creeks or bays in which the Norsemen

anchored, or where they ran their boats ashore, are called by Norwegian

names, from Wick, the greatest fishing station in the world, to Freswick,

Sleswick, Dwarwick, and such like inlets.

The Gaels seem to have been pushed inland towards the hilly country of

Sutherland, while the Scandinavians occupied the low-lying ground along the

coast. Almost every farm steading is called by a Scandinavian name. Hence

Scrabster, Lybster, Seister, Thurster, Ulbster, and such like—the word ster

being from “saetr,” the Scandinavian word for farm. Dahls, or dales,

penetrate the country to the southward, though the Celtic word Strath is

still preserved. Hence Strath Halladale and Strath Helmsdale in

Sutherlandshire. North of that region, the rivers are called forss or water.

Worsaae derives the name of Thurso from Thor the pagan god, and aa a river.

Hence Thorsa, or Thor’s river.

The people also resemble their progenitors. The fair hair, blue eyes, and

tall figures of the Scandinavians are still preserved throughout the

county,—in contradistinction to the small size, the dark hair, the swarthy

skin, and the black or steely-blue eyes of the Celts, to the south and west

of Scotland.

All the firths, or inlets of the sea, are known by Norse names. The Pentland

Firth, which runs between the north coast of Caithness and the Orkneys, was

in old Norse called the Petland Fiord. Here we have the mythical Picts

again. Bleau, in his Geographical Atlas, says that the Piets, when defeated

by the Scots, fled to Duncansby, from whence they crossed to Orkney. But,

meeting with resistance by the natives, they were forced to return. On their

way back to Caithness, they all perished in the firth; from which

catastrophe it was ever after called the Pictland or Pentland Firth.

Heavy currents run through the Firth. The tide runs at the rate of ten miles

an hour. A full-rigged ship, with her sails set and a favourable wind, is

sometimes driven back by the tide. This I have seen when journeying along

the shores of the Firth. Sometimes it is whirled round amidst the eddying

currents. Where the currents of the Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea meet,

the water is churned and eddied about as in a maelstrom. At the east end of

the Firth is the island of Stroma, which in old Norse means “ the island in

the current.” The population of the island is of pure Norwegian descent; the

men being excellent sailors and boatmen.

Not far from this island, and in sight of John o’ Groat’s, are the two

Pentland Skerries, commanding the eastern entrance to the Firth. They were

originally called Petland Skjaere. The largest skerry contains two

lighthouses, one higher than the other, to be a surer guide to the mariner.

During the equinoctial gales, the wind sweeps across the county with great

fury. It is scarcely possible to hold one’s feet. Cattle are blown down, and

trees are blown away. The thatched roofs of the cottages are held down by

strong straw ropes with heavy stones hanging at their ends; otherwise the

roofs would be blown away, as well as the cottages themselves.

It is scarcely possible to grow a tree in the northern part of the county.

Hedges are almost unknown. Instead of hedges, the fields are separated from

each other by Caithness flags set on end. To one accustomed to the beautiful

woods and hedgerows of the south, the cheerlessness of Caithness scenery may

well be imagined. Robert Chambers said of the county—“ The appearance of

Caithness is frightful, and productive of melancholy feelings.” “It is only

a great morass,” says another writer; “ the climate is unfavourable; the

stormy winds are always blowing across it; mists suddenly come on, and the

air is always damp.”

A desperate effort has been made to grow trees at Barrogill Castle, within

sight of the Pentland Firth. A wood surrounds the east side of the castle.

The trees are planted thick, and they are protected by a high wall. But at

the point at which the wall ends, the tops of the trees are sharply cut away

as if by a scythe. They are chilled and eaten down by the sea-drift.

The best wood in the northern part of the county is at Castlehill, where the

imported trees are protected by rising grounds on all sides. The only tree

that thrives in Caithness is the common bourtree or elder. The trembling

poplar, the white birch, and the hazel, are also occasionally found in

sheltered places.

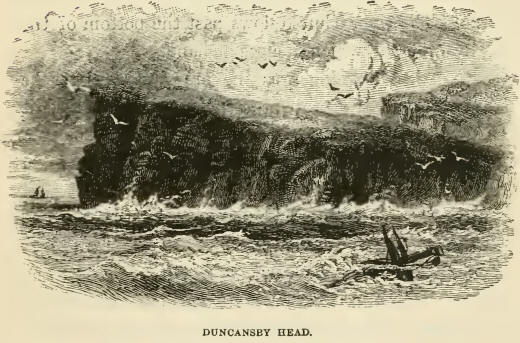

But though the county of Caithness is for the most part flat and cheerless,

it is redeemed from monotony by its glorions coast scenery. On the east, as

well as on the west, the rocks jut out into the ocean in stupendous cliffs.

“When the stormy winds do blow” is the time to see the wonders of the

north—at Duncansby Head, at Dunnet Head, at Holborn Head, at Noss Head, and,

indeed, all round the coast. At Wick Bay, only a few years ago, a tremendous

storm from the east dashed to pieces the new breakwater, lifting up stones

of tons weight and dashing them on the beach,—thus setting at defiance the

skill and ingenuity of the engineer who had built it.

Duncansby Head is also exposed to the full fury of the North Sea. It is a

continuous precipice about two miles in extent, and of a semicircular shape.

It is remarkable for its stupendous boldness, and the wild and striking

appearance of the chasms and goes by which it is indented. In front of the

cliff are three Stacks, which have been washed round by successive storms,

and stand out bare and red several hundred yards from the mainland. The

cliff consists principally of old red sandstone, and partly of Caithness

slate.

The huge, long, white-crested billows, lashed into fury by the storm, chase

each other up the beach, and burst with astounding force. At high tide, they

dash up the cliffs and rush over the summit into the mainland. Fiom thence

they run down over the inland slopes, into a rivulet which joins the

Pentland Firth near John o’ Groat’s. From the summit of the cliff a fine

view is obtained of the Skerries at the mouth of the Firth, of Stroma, the

island in the current, and of the Orkney Islands as far as the bold headland

of Hoy.

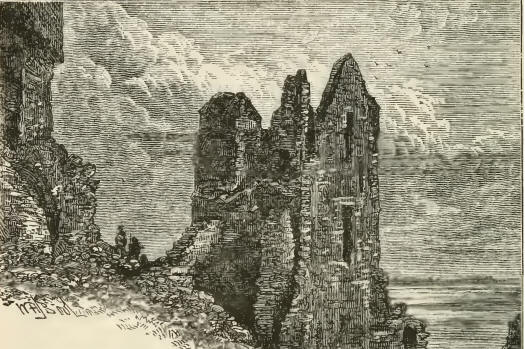

Along the east coast, numberless castles are built upon the cliffs. They are

mostly in ruins. Many ol them are prehistoric. Wick Castle, Girnigo Castle,

and Keiss Castle, are the oldest. Ho one knows who built them. Most probably

they are the strongholds of the Scandinavian chiefs, who, at some unknown

period, took possession of the lowland part of the county.

The castle of Al-Wick—or, as it is usually called, the Auld Man of

Wick—seems to be one of the most ancient. It consists of a grim-looking

tower or keep of the rudest masonry, perforated here and there with

arrow-slits. It is three stories high; but entirely roofless and floorless.

It is surrounded by an outer wall, within which are the ruins of some old

houses. A deep broad moat defends it on the land side. At present, it forms

an excellent landmark to vessels approaching that part of the coast.

Girnigo Castle, situated on the promontory of Hoss Head, is also very old.

Castle Sinclair, which was added to it, has a history, which Girnigo has

not. But the old builders were so much better than the new ones, that while

Castle Sinclair has fallen to ruins, Girnigo Castle stands as firmly as it

did at the time at which it was built.

The constantly rolling sea, ever for ever, washes itself against the rocks,

grinding away the softest parts. The red sandstone goes first, leaving long

hollows amongst the slates, through which the sea drives inland. In stormy

weather, the waves wash in with

great force, sometimes a quarter of a mile or more; and at theS~^ far end,

they drive up into the open air, blowing like a whale. '

These hollows under the rocks are called goes or gyoes. They are common V

all round Caithness. One of them is near Wick, at the castle of Al-Wick.

Girnigo castle.

Robert Dick describes another

near Thurso, which will be found referred to in a future part of the story.

From the northern part of

Caithness, where the >N11 ground is comparatively flat inland, and full of

lochs from Thurso to Wick, the land gradually ascends, until we find hills

and then mountains close upon the borders of Sutherland. Morven, Maiden Tap,

and Skerry Ben, form part of a range of mountains, extending from Sandside

Bay on the north, to Helmsdale on the south. Morven is the great mountain of

Caithness. It is 2331 feet high. It is regarded as the great weather-glass

of the county. When the mist gathers about its base, rain is sure to follow;

but when the mist ascends to the top and disperses, leaving the majestic

outline of the mountain exposed to view, then the weather will be fine.

“During harvest especially,” says a local writer, “all eyes are directed

towards it; and it never deceives.

“In vision I behold tall

Morven stand,

And see the morning mist distilling tears

Around his shoulders, desolate and grand.”

From what we have already

stated, it will be understood that Caithness is by no means a fertile

county. Until a comparatively recent period agriculture was in a very

backward state. When Pennant visited the county about a hundred years ago,

he describes it as little better than “an immense morass,” with here and

there some fruitful spots of oats and bere, and much coarse grass.

In those places where any agriculture was carried on, the women did the work

of horses. They carried the manure on their backs to the field; and did the

most of the manual labour. The land could scarcely be called ploughed. The

Caithness plough was one-stilted. It was dragged over the ground by a yoke

of oxen, driven by a woman. There were neither barns nor granaries in the

county. The corn was preserved in the chaff in bykes, which were low stacks

in the shape of bee-hives, thatched quite round.

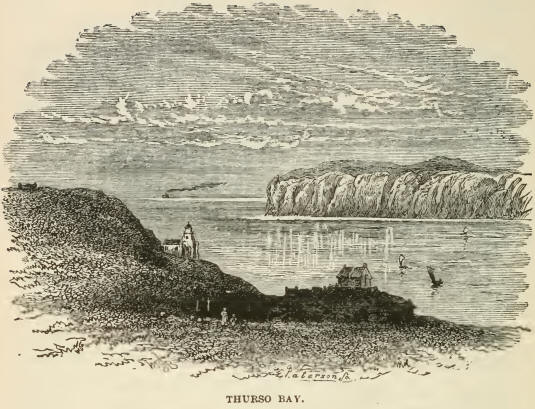

Thurso, the chief place in Caithness, carried on a trade with Norway and

Denmark, long before it began to communicate with the rest of Scotland. The

sea was by far the easiest mode of transit; and all the people along the

coast were sailors. But, indeed, there was very little traffic to be carried

on. The only two clusters of houses in the county were Thurso and Wick.

Thurso must have been the more important place, as it not only had a church,

but also a bishop— the Bishop’s Palace being close at hand. Thurso was a

small fishing town, and Wick contained only a few hundred inhabitants. But

the fishing has long left Thurso, and gone to Wick. “The only fishing at

Thurso now,” said Dick, “is sillocks and sillock scrae. The salmon fishing,

however, is the best in the kingdom.”

There were then no roads in Caithness. The extensive hollows in the flat

slaty ground were filled with morasses. There was not a single wheel-cart in

the county before 1780. Crubbans were the substitutes for carts. They were

wicker baskets. Two of them, hung one on each side of a pony from a wooden

saddle, beneath which was a cushion of straw, carried corn, goods, and other

articles. Six or seven ponies thus loaded, says Henderson in his

Agricultural Survey of Caithness, might be seen going in a kind of Indian

file, each tied by the halter to the other’s tail, a person leading the

front horse, and each of the others was pulled forward by the tail of the

one before him. Yet traffic was carried on throughout England in the same

manner, about three hundred years ago.

Caithness was behind in everything. The only geography of the county was

known from Danish sources. Timothy Pont made his first map in 1608. It was

shut out from the rest of Scotland by the mountainous county of Sutherland.2

It was long before a road could be made to enable the people to communicate

with their countrymen farther south. The only road lay along the eastern

shore, among rocks and sand, which were often covered by the tide. The

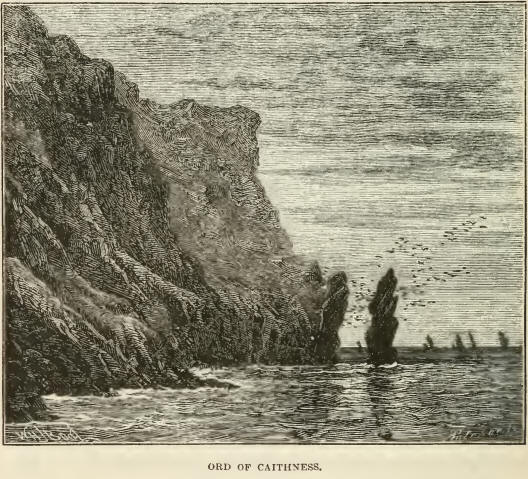

inland road lay over the Ord of Caithness. The Ord is a formidable pass

between Sutherland and Caithness. It is situated at the eastern boundary of

the two counties. There is a lofty mountain on one side of the road, and a

steep precipice on the other, at the foot of which is the sea.

The Ord is the termination of a long mountain ridge, and is the brow of a

steep hill overhanging the ocean. On the Sutherland side, the headland is

cleft into a gorge of great depth, which runs a long way inland. The old

road—before the present bridge was built over the gorge —was a mere path or

shelf along the outer edge of the promontory twelve hundred feet above the

sea. When

the weather was stormy, it could not he passed in safety. Even in fair

weather, the road was so difficult and dangerous that, when the chaise of a

landed proprietor had to pass it, a force of fifteen or twenty persons was

employed to help on the carriage and horses.

Pennant, who travelled into

many strange places, described the pass as “infinitely more high and

horrible than Penmaenmaur in Wales and another writer says, J that if any

stumble thereupon, they are in danger of falling down a precipice into the

sea at the bottom of the rock, which is very terrible to behold.” The old

path is still to be seen from Helmsdale. It is like a sheep-track winding up

the steep brow of tlie hill, some three or four hundred feet above the

rolling surge.

The road to Thurso from the Ord road was almost impassable. It was a mere

horse track over the hill of Bencheilt. This road was made passable for

carriages through the energy of Sir John Sinclair. The Abbe Gregoire

denominated Sir John “the most indefatigable man in Europe.” To him the

improvement of the county of Caithness in a great measure belongs. He was

born at Thurso Castle, an ancient edifice built by the' sixth Earl of

Caithness. It has since been pulled down to make room for a spick-and-span

new castle, much less picturesque than the old one. It stood almost 'within

sea-mark on Thurso Bay. In stormy weather, the sea spray sometimes passed

over the roof. Miss Catherine Sinclair has said that fish have been caught

with a line from the drawing-room window; and vessels have been wrecked so

close under the turrets, that the voices of the drowning sailors have been

heard.

When Sir John succeeded to his estates, three-fourths of Caithness consisted

of deep peat-moss, and of hills covered with heath, or altogether naked. On

arriving at his majority, he determined upon the improvement of his estates,

and of the county generally. One of the first things that he did was to

endeavour to make a roaci to Thurso over Bencheilt, in the centre of the

county. He himself surveyed the road and marked out its lines. He called

together twelve hundred and sixty labourers to meet him early one morning,

and set them all simultaneously to work. They began at the dawn of day, and

before nightfall, the sheep-track, six miles in length, was converted into a

road perfectly easy for carts and carriages. This showed what energy could

accomplish.

The young laird was not satisfied with that. He formed a large number of

farms on his own estate. He enclosed, drained, and reduced them to order,

entirely at his own expense. He built bridges; he made roads; he introduced

the best cattle; he provided the best turnip, rye-grass, and clover seeds;

he enjoined upon his farmers to adopt a regular rotation of crops; and in a

short time converted what had been a barren wilderness into a

well-cultivated district. He enclosed on his own estate about 12,000 English

acres of waste land, all of which eventually repaid the outlay. Among his

other achievements, he introduced the Cheviot breed of sheep into the whole

of Scotland, and thus doubled the value of the grazing grounds north of the

Tweed.

Sir John tried to introduce trees at Thurso, but he found it difficult to

make them grow. It was necessary to dig a hole of large dimensions through

the subsoil of slaty rock, over which the tenants of the neighbouring

townlands were obliged annually, for seven years, to heap a large mound of

compost. And even when the trees did grow they were often blown away by the

furious winds from the north and west.

Sir John even tried to introduce nightingales into Caithness! But Nature

baffled his efforts. He obtained nightingales’ eggs from the London bird

fanciers. They were substituted for those of the robin redbreast. The eggs

were hatched. The young nightingales soon flew about the bushes round Thurso

Castle. But so soon as the summer had ended, the birds disappeared and never

returned.

|