|

Robert Dick was apprenticed

to Mr. Aikman, a baker in Tullibody, when he was thirteen years old. Mr.

Aikman had a large business, and supplied bread to people in the

neighbouring villages as far as the Bridge of Allan.

The life of a baker is by no means interesting. One day is like another. The

baker is up in the morning at three or four. The oven fire is kindled first.

The flour is mixed with yeast and salt and water, laboriously kneaded

together. The sponge is then set in some warm place. The dough begins to

rise. After mingling with more flour, and thorough kneading, the mass is

weighed into lumps of the proper size, which are shaped into loaves and

“bricks,” or into “baps,” penny and halfpenny. This is the batch, which,

after a short time, is placed in the oven until it is properly baked and

ready to be taken out. The bread is then sold or delivered to the customers.

When delivered out of doors, the bread is placed on a flat baker’s basket,

and carried on the head from place to place.

Robert Dick got up first and kindled the fire, so as to heat the oven

preparatory to the batch being put in. His nephew, Mr. Alexander of

Dunfermline, says “he got up at three in the morning, and worked and drudged

until seven and eight, and sometimes nine o’clock at night.”

As he grew older, and was strong enough to carry the basket on his head, he

was sent about to deliver the bread in the neighbouring villages. He was

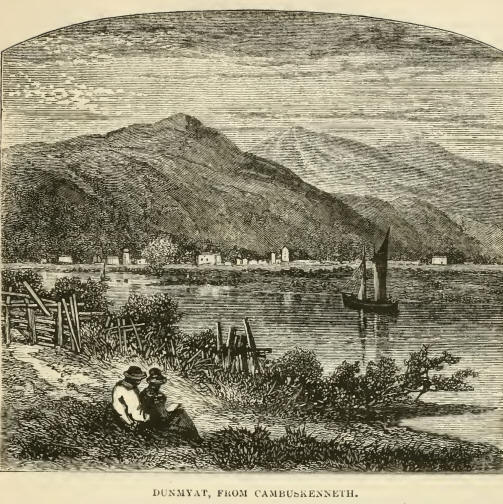

sent to Menstrie, to Lipney on the Ochils, to Blairlogie at the foot of

Dunmyat, and farther westward to the Bridge of Allan, about six miles from

Tullibody.

The afternoons on which he delivered the bread were a great pleasure to

Dick. He had an opportunity for observing nature, which had charms for him

in all its moods. When he went up the hills to Lipney, he wandered on his

return through Menstrie Glen. He watched the growth of the plants. He knew

them individually, one from the other. He began to detect the differences

between them, though he then knew little about orders, classes, and genera.

When the hazel-nuts were ripe he gathered them and brought loads of them

home for the enjoyment of his master’s bairns. They all had a great love for

the ’prentice Robert.

He must also, in course of time, have obtained some special acquaintance

with botany. At all events, he inquired, many years after, about some

particular plants which he had observed during his residence at Dam’s Burn

and Tullibody. "Send me,” he said to his eldest sister, “a twig with the

blossom and some leaves, from the Tron Tree in Tullibody.” The Tron Tree is

a lime tree standing nearly opposite the house in which Robert was born.

“Send me also,” he said, “a specimen of the wild geranium, which you will

find on the old road close by the foot of the hills between Menstrie and

Alva. I also want a water-plant [describing it] which grows in the river

Devon.” The two former were sent to him, but the water-plant could not be

found.

Robert’s apprenticeship lasted for three years and a half. He got no

wages—only his meals and his bed. He occupied a small room over the

bakehouse. His father had still to clothe him, and his washing was done at

home. On Saturdays he went with his “duds” to Dam’s Burn. But either soap

was scarce, or good-will was wanting. His step-mother would not give him

clean stockings except once a fortnight. His sister Agnes used to accompany

him home to Tullibody in the evening, and at the Aikmans’ door she exchanged

stockings with him, promising to have his own well darned and washed by the

following Sunday.

The day of rest was a day of pleasure to him. He did not care to stay within

doors. He had shoes now, and could wander up the hills to the top of Dunmyat

or Bencleuch, and see the glorious prospect of the country below; the

windings of the Devon, the windings of the Forth, and the country far away,

from the castle of Stirling on the one hand to the castle of Edinburgh on

the other.

Dick continued to be a great reader. He read every book that he could lay

his hands on. Popular books were not so common then as they are now. But he

contrived to borrow some volumes of the old Edinburgh Encyclopaedia, and

this gave him an insight into science. It helped him in his knowledge of

botany. He could now find out for himself the names of the plants; and he

even began to make a collection. It could only have been a small one, for

his time was principally occupied by labour. Yet, with a thirst for

knowledge, and a determination to obtain it, a great deal may be

accomplished in even the humblest station.

In 1826, Mr. Dick was advanced to the office of supervisor of excise, and

removed to Thurso. Robert was then left to himself in Tullibody. He had

still two years more to serve. One day followed another in the usual round

of daily toil. The toil was, however, mingled with pleasure, and he walked

through the country with his bread basket, and watched Nature with

ever-increasing delight.

He made no acquaintances. The Aikmans say “that he was very kind to his

master’s children—that he was constantly bringing them flowers from the

fields, or nuts from the glens, or anything curious or interesting which he

had picked up in the course of his journeys.” He occupied a little of his

time in bird-stuffing. He stuffed a hare, which he called “a tinkler’s

lion.” It need scarcely be said that the children were very fond of their

father’s ’prentice.

At length his time was out. He was only seventeen. But he had to leave

Tullibody, and try to find work as a journeyman. He bundled up his clothes

and set out for Alloa, where he caught the boat for Leith. He never saw

Tullibody again, though he long remembered it. His father and mother were

buried in the churchyard there; and he could not help having a longing

affection for the place. But he could never spare money enough to revisit

the place of his birth.

Long after, when writing to his brother-in-law, he said,—“And ye have been

up to Alloa. Well, I do believe that is a bonnie country, altho’ I fancy it

is not in any sense the poor man’s country. Nothing but men of money there;

though fient a hair did I care for their grandeur while I lived there. The

hills and woods, and freedom to run upon them and through them, was all I

cared about.

“What though, like commoners of air,

We wander out we know not where,

But either house or hall?

Yet Nature’s charms, the hills and woods,

The sweeping vales, and foaming floods,

Are free alike to all."

I daresay I might pick up a plant or a stone with very different feelings

from those I felt in the days of old. But let them go! There is no use in

repining.”

Again, when writing to a fellow botanist, who doubted whether Digitalis

ymrpurea was a native of Caithness, he said, “I have seen more of the plant

in Caithness than I ever saw about Stirling, Alloa, or on the Ochil

hills,—more than I ever saw in the woods of Tullibody.”

Robert Dick found a journeyman's situation at Leith, where he remained for

six months. His life there was composed of the usual round of getting up

early in the morning, kneading, baking, and going about the streets with his

basket on his head, delivering bread to the customers. It was a lonely life;

and the more lonely, as he was far away from Nature and the hills that he

loved.

From Leith he went to Glasgow, and afterwards to Greenock. He was a

journeyman baker for about three years. His wages were small; his labour was

heavy; and he did not find that he was making much progress. He continued to

correspond with his father, and told him of his position. The father said,

“Come to Thurso, and set up a baker’s shop here.” There were then only three

bakers’ shops in the whole county of Caithness,— one at Thurso, one at

Castleton, and another at Wick.

In that remote district “baker’s bread” had scarcely come into fashion. The

people there lived chiefly on oatmeal and bere,—oatmeal porridge and cakes,

and barley bannocks, with plenty of milk. Upon this fare men and women grew

up strong and healthy. Many of them only got a baker’s loaf for “the

Sabbath.”

Robert Dick took his father’s advice. He went almost to the world’s end to

set up his trade. He arrived at Thurso in the summer of 1830, when he was

about twenty years old. A shop was taken in Wilson’s Lane, nearly opposite

his father’s house. An oven had to be added to the premises before the

business could be begun; and in the meantime Robert surveyed the shore along

Thurso Bay.

Thurso is within sight of Orkney, the Ultima Thule of the Romans. It is the

northernmost town in Great Britain. John o’ Groat’s—the Land’s End of

Scotland —is farther to the east. It consists of only a few green mounds,

indicating where John o’ Groat’s House once stood.

Thurso is situated at the southern end of Thurso Bay, at the mouth of the

Thurso river,—the most productive salmon river in Scotland. The fish, after

feeding and cleaning themselves in the Pentland Firth, make for the fresh

water. The first river they come to is the Thurso, up which they swim in

droves.

Thurso Bay, whether in fair or foul weather, is a grand sight. On the

eastern side, the upright cliffs of Dunnet Head run far to the northward,

forming the most northerly point of the Scottish mainland. On the west, a

high crest of land juts out into the sea, forming at its extremity the hold

precipitous rocks of Holborn Head. Looking out of the hay you see the Orkney

Islands in the distance, the Old Man of Hoy standing up at its western

promontory, At sunset the light glints along the island, showing the hold

prominences and depressions in the red sandstone cliffs. Out into the ocean

the distant sails of passing ships are seen against the sky, white as a

gull’s wing.

The long swelling waves of the Atlantic come rolling in upon the beach. The

noise of their breaking in stormy weather is like thunder. From Thurso they

are seen dashing over the Holborn Head, though some two hundred feet high;

and the cliffs beyond Dunnet Bay are hid in spray.

Robert Dick was delighted with the sea in all its aspects. The sea opens

many a mind. The sea is the most wonderful thing a child can see; and it

long continues to fill the thoughtful mind with astonishment. The sea-shore

on the western coast is full of strange sights. There is nothing but sea

between Thurso and the coasts of Labrador.

The wash of the ocean comes by the Gulf Stream round the western coasts of

Scotland, and along the northern coasts of Norway. Hence the bits of

driftwood, the tropical sea-weed, and the tropical nuts, thrown upon the

shore at Thurso.

In the same way, bits of mahogany are sometimes carried by the ocean current

from Honduras or the Bay of Mexico, and thrown upon the shore on the

northern most coasts of Norway. One evening, while walking along the beach

near Thurso, Robert Dick took up a singular-looking nut, which he examined.

He remarked to the friend who accompanied him, “That has been brought by the

ocean current and the prevailing winds all the way from one of the West

Indian Islands. How strange that we should find it here!”

Robert Dick always admired the magnificent sea pictures of Thurso Bay—its

waves that gently rocked or wildly raged. He enjoyed the salt-laden breath

of the sea wind; and even the cries of the sea birds. Here is his

description of the sea-mew: “Ha ga tirwa!’ How strange and uncouth ! How

very unnatural the cry seemed. It was only the cry of a sea bird. It was

within sight of the ocean. There had been a storm. It was over, but the

waves in long rolling breakers dashed themselves in a rage on the sandy

shore, and then were quiet. But quiet only for a moment. ‘Ha ga tirwa!’

Restless and unwearied, another and another long wave followed and burst

into spray. And thus it has ever been ‘since evening was, and morning was.’

It was then evening, the stars began to twinkle; and after a little the full

moon rose. But still ‘Ha ga tirwa!’”

But before proceeding with Robert Dick’s history, it is necessary that we

should give a short account of the county of Caithness, over the whole of

which he afterwards wandered in search of the botany, as well as of the

geological formation of the district. |