|

Robert Dick was born at

Tullibody in January 1811. He was one of four children—Agnes, Robert, Jane,

and Janies.

Thomas Dick, his father, was an officer of excise. He was an attentive,

diligent, and able man. He eventually rose to one of the highest positions

in his calling. At the time when Robert Dick was born, it was his business

to attend daily at the Cambus Brewery, close at hand.

Margaret Gilchrist was Robert Dick’s mother. Very little is known of her,

excepting that she was a very delicate woman, and died shortly after having

given birth to her fourth child. Thomas Dick was thus left without a wife,

and his children without a mother.

The house in which the Dick family lived, and in which Robert was born, is

situated in the principal street of the village. It is a two-storied,

red-tiled, “self-contained” house. Looking down the street from the Tron

Tree, you see the Ochil hills forming the back-ground of the village; the

Devon winding in the valley below.

The children, as they grew up, were sent to school. Tullibody was fortunate

in its Barony School, founded and partly endowed by the Abercromby family.

Thus all the children in the village were able to obtain a fair education at

a moderate price; for in Scotland it is considered a disgrace if a parent,

of even the meanest condition, does not send his children to school.

Mr. Macintyre was the teacher of the Barony School He was a man of

considerable attainments. Above all things, he was an enthusiastic

schoolmaster. He maintained discipline, inculcated instruction, and elevated

the position of his school by steady competition. He endeavoured to avoid

corporal punishment, and only appealed to it as the last resource.

Robert Dick was one of his aptest scholars. He learned everything rapidly.

When he had mastered reading, he read everything he could lay hands on. He

was fond of fun and sport, and, like all strong and active hoys, he

sometimes got into scrapes. When he infringed the rules of the school, the

master gave him a number of verses to commit to heart. But he learnt them so

quickly and recited them with such ease, that the task was found of no use

as a punishment, and then, on any further indiscretion being committed, the

master resorted to the last extremity—the Taws! In a letter to Hugh Miller,

Dick afterwards said, “My auld dominie used to say that I had a good memory.

Every morning, in his introductory exercise, before the business of the day

began, he used to pray that teacher and scholars might all be taught, and

that discipline might be followed with obedience.”

Robert had a great talent for languages. He learnt Latin so quickly that his

master recommended Mr. Dick to send him to college, with the object of

educating him for one of the learned professions. Such was his intention,

when an event occurred which prevented its being carried into effect.

This was Mr. Dick’s second marriage. It occurred in 1821, when Robert was

ten years old. Mr. Dick married the daughter of Mr. Knox, the brewer at

Cambus, whose premises he inspected. As the excise regulations did not

permit of his surveying the premises of a relative, he was removed to Dam’s

Burn, a hamlet at the foot of the Ochils, where he inspected the whisky

distillery of Mr Dali. The distillery is now called Glen Ochil.

Dam’s Burn is so called because of a noisy burn, which leaps from rock to

rock down the hills, to join the Devon, which runs through the valley below.

On its way, the burn used to be dammed up, so as to drive a mill while on

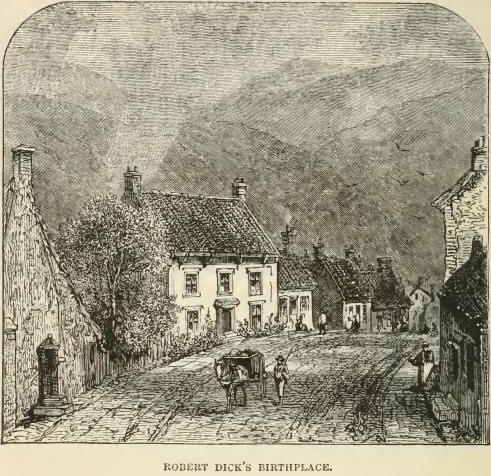

its way to the river. Mr. Dick occupied the best house in the place, the

slated house, with its gable end towards the street, as shown in the annexed

engraving. The slopes of the Ochil hills,— the Abbey Craig, on which the

Wallace Monument now stands, and the Campsie Fells, beyond Stirling, are

seen in the distance.

While at Dam’s Burn, Robert Dick went to the parish school at Menstrie, a

village about half a mile westward.

The teachers name was Morrison. He was not equal in accomplishments to the

Barony schoolmaster at Tullibody. He took to teaching because he had not

limbs enough to fit him for anything else. He had only one arm. He used to

mend his pens dexterously, while holding them firmly under the little stump

that remained on the other side.

Robert Dick made little progress under this master. He learned his lessons

well enough, and read as many books as he could find or borrow. But he had a

great compensation at Dam’s Burn for his want of school learning. It was at

Dam’s Burn that he imbibed his love of Nature. The green Ochils rose right

behind his father’s house. By stepping into the back-green, he could at once

ascend the heights. He could ramble up the burns, and in the sheltered

corners, behind the rocks, find many precious flowers and plants.

The boy who plays about a mountain side, or among the clefts of the hills,

finds many things to amuse him. In spring time there are the birds; in

summer there are the plants and flowers; and in winter there are the icicles

hanging down the ledges of the rocks. Robert also found out a variety of

stones among the hills,— the felspar, porphyry, and greenstones, which are

common in the Ochils. He wondered at the difference between them,—made a

collection of them, which he treasured at a dike-side, behind his father’s

house,— and tried to find out the cause of the difference between one stone

and another.

This climbing of the Ochils led him into difficulties.

And this leads us to a point in the history of Robert Dick’s life which

cannot be omitted, inasmuch as it coloured his whole future life. The years

of childhood and boyhood are, as it were, a sort of prophetic recital of the

years of manhood. They constitute the little stage on which, with puny

powers, we unconsciously rehearse the scenes of after life.

The boy has in him the seeds of good and the seeds of evil. Which will prove

the stronger? No one can tell. But, to a large extent, it depends upon the

effects of love and sympathy at home. The presence of these may call into

life the best growths of the soul, and the absence of them may raise up the

noxious miasmas that poison the whole human heart.

It will be remembered, that when Thomas Dick removed to Dam’s Burn, he

married again. Other children were soon added to the household. Then the

feelings of the step-mother came into play. It requires great tact and

temper to manage a family in which there are two elements,—the children of

the first mother, and the children of the second.

The new Mrs. Dick was a good wife and an excellent mother, so far as her own

children were concerned. But she did not get on well with her husband’s

children by his first wife. Perhaps they regarded her as an intruder Li the

household; and where her own children were concerned, she naturally regarded

them with preference.

Nor were her husband’s attentions to his children by his first wife at all

to her taste. What was done for them evoked many a pang of maternal

jealousy. Mother-like; human-like, she could not but regard these young

things as intruders upon her own children’s standing room. All that was

given to them was so much taken from her own offspring.

Hence arose family difficulties in the household. Robert stayed out, rather

than remain indoors. He wandered about among the hills. He wore out his

shoes. To prevent him going out, his step-mother hid them. Still Robert

climbed the hills, and came home with bleeding feet. He was punished for his

misdoings, and commanded to stay at home. This did not hinder him from going

out again. He would wander along the Devon looking for birds’ nests. This

was as bad as climbing the Ochils, and he was again thrashed with a stick.

It was the same with the other step-children. James, the youngest son of the

first wife, struck back. Poor fellow! He was pommelled so hard that he could

scarcely stand. Was he a “dour,” hard, perverse boy? Very likely. He had no

mother’s affection to bear him up. Robert Dick never complained. He took his

thrashings without grumbling. Still he went on in his old way, though he

could not but feel the hollowness of his new motherhood.

At last the children were got out of the house, Instead of being sent to

college (as had been his father’s intention), Robert was sent to Tullibody,

where he was apprenticed to a baker. Shortly after, James, the youngest boy,

went to sea; and Agnes, the eldest, went to be a servant at Edinburgh.

Of course this was a very bad training for an intelligent, high-spirited

boy. It was not calculated to liberate the ideal human being which lies

concealed in every child. It was, on the contrary, calculated to sour the

boy’s nature, and to thwart his temperament at every point. It threw a dark

shadow along the whole of his future life.

Long afterwards, in speaking to Charles Peach about his early struggles, he

said—“All my naturally buoyant, youthful spirits were broken. To this day I

feel the effects. I cannot shake them off. It is this that still makes me

shrink from the world.” It will be necessary to bear these facts in mind

while reading the story of Eobert Dick’s after life.

There were, however, two or three things that Robert had already learnt. He

was educated, as Scotch boys usually are, at the parish school. He had

learnt reading, writing, arithmetic, and a little Latin. It did not amount

to much, but it was the beginning of a great deal. The rest of his education

he owed to himself. As Stone, the son of the Duke of Argyll’s gardener,

said, “One needs only to know the twenty-six letters of the alphabet to be

able to learn everything else that one wishes.”

Another thing that he learnt during this trying period of his life, was

self-control. Though treated with capricious restraint, he never retorted.

He bore uncomplainingly all that was laid upon him. Though strong and

spirited, he was a good-natured boy. He felt that, under the circumstances,

the ill-treatment of his stepmother was a thing that he must bear; and he

bore it uncomplainingly, looking forward to better times.

There are compensations in all things. He was happy to leave home. It was a

pleasure to him to find that there was some other roof under which he could

live in comparative comfort. |