|

MY BONNY BROOMY KOWE.

Tune—The Nameless Lassie.

In summers past I've seen thee

bloom

On mossy bank and knowe;

I've revell'd mid thy sweet perfume,

My bonny broomy kowe.

I've garlanded thy yellow flowers,

I've lain beneath thy bough;

I'll ne'er forget thy youthful prime,

My bonny broomy kowe.

You've been my friend at ilka

spiel,

You've polish'd up the hone,

You've mony a stane brocht owre the hog,

My bonny broomy kowe.

As mem'ry noo recalls the past,

My heart is set alowe,

Wi' moistened e'en I gaze on thee,

My bonny broomy kowe.

Time tells on a'; your pith

has gane,

And wrinkled is my brow

We're no sae fresh as we ha'e been,

My bonny broomy kowe.

Your wizzen'd sair, and maist as thin

As hairs upon nay powv,

I doubt our days are nearly dune,

My bonny broomy kowe.

When death comes o'er me, let

my grave

Be sacred frae the plough;

For cypress plant a golden broom,

That yet may be a kowe.

Nor rest nor peace shall e'er be yours—

A' curlers hear my vow

Unless there grow abune my head

A bonny broomy kowe.

W. A. PETERKIN.

CURLING EQUIPMENTS

Hearken, thou craggy ocean

pyramid!

Give answer from thy voice—the sea-fowls' screams

When were thy shoulders mantled in huge streams?

When, from the sun, was thy broad forehead hid?

How long is't since the mighty power bid

Thee heave to airy sleep from fathom dreams?

Sleep in the lap of thunder or sunbeams,

Or when grey clouds are thy cold coverlid?

Thou answer'st not, for thou

art dead asleep

Thy life is but two dead eternities—

The last in air, the former in the deep;

First with the whales, last in the eagle-skies

Drown'd wast thou till an earthquake made thee steep,

Another cannot wake thy giant size.

(FIRST.)

UT

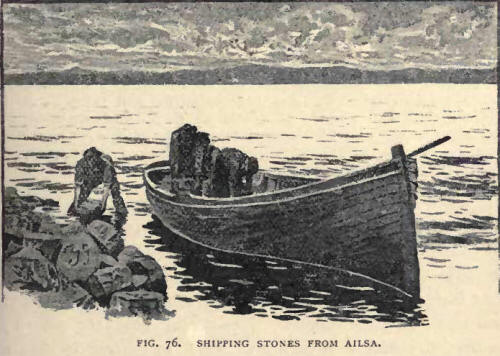

from the entrance to the Frith of Clyde stands "the craggy ocean pyramid"

which John Keats, in that fine sonnet, apostrophised as he halted at the

King's Arms Inn, Girvan, in the summer of 1818. But Ailsa Craig, still as

deaf as when Burns told the tale of Keg and Duncan Gray, neither heard nor

Heeded the questioner. About the very time that Keats wrote his sonnet Ailsa

Craig was becoming known as "a place of arms" for curlers. As such it has

become more and more popular. We are within the mark when we say that

one-half of the curling-stones used in Scotland, and three-fourths of those

furth of Scotland, have been taken from Ailsa. The chief equipment of the

curler is his curling-stone. While the frost lasts, that stone is the

dimidium animœ of its owner—aye, and more. It cannot but be interesting to a

curler to know something as to how his chief equipment is itself equipped.

In this belief we ask him to accompany us to the Craig, and follow the

career of the stone. The origin of the rock itself we had better regard as a

mystery, like the origin of the game of curling and of the Royal Club. Any

answer to the poet's questions seems to open up awkward points. We are safe

enough to believe that Hew Barclay of Ladyland tried to make Ailsa a

fortified place, to help the cause of Spain and that for his treason he

shared the fate of the Armada, or that the solan geese were its

"inhabitants" as far back as 1549, when Dean Munro of the Isles wrote the

first account of the rock. Beyond that the ground is dangerous. One

tradition is that about the year 1000 A.D. the island belonged to the Irish

king, Brian Boru. If so, pity the Marquis of Ailsa, the tenant, and the

stone-makers! According to the Irish song: UT

from the entrance to the Frith of Clyde stands "the craggy ocean pyramid"

which John Keats, in that fine sonnet, apostrophised as he halted at the

King's Arms Inn, Girvan, in the summer of 1818. But Ailsa Craig, still as

deaf as when Burns told the tale of Keg and Duncan Gray, neither heard nor

Heeded the questioner. About the very time that Keats wrote his sonnet Ailsa

Craig was becoming known as "a place of arms" for curlers. As such it has

become more and more popular. We are within the mark when we say that

one-half of the curling-stones used in Scotland, and three-fourths of those

furth of Scotland, have been taken from Ailsa. The chief equipment of the

curler is his curling-stone. While the frost lasts, that stone is the

dimidium animœ of its owner—aye, and more. It cannot but be interesting to a

curler to know something as to how his chief equipment is itself equipped.

In this belief we ask him to accompany us to the Craig, and follow the

career of the stone. The origin of the rock itself we had better regard as a

mystery, like the origin of the game of curling and of the Royal Club. Any

answer to the poet's questions seems to open up awkward points. We are safe

enough to believe that Hew Barclay of Ladyland tried to make Ailsa a

fortified place, to help the cause of Spain and that for his treason he

shared the fate of the Armada, or that the solan geese were its

"inhabitants" as far back as 1549, when Dean Munro of the Isles wrote the

first account of the rock. Beyond that the ground is dangerous. One

tradition is that about the year 1000 A.D. the island belonged to the Irish

king, Brian Boru. If so, pity the Marquis of Ailsa, the tenant, and the

stone-makers! According to the Irish song:

"Bad luck to the gosoon

spalpeen,

Or Saxon idle drone,

Who would make filthy lucre

Out of Brian's blessed stone."

If, as another tradition

reports, the witches dropped Paddy's milestone in the North Channel on their

way over to Ireland, then there are more curlers than those at Monzie

[Called Maggie Culzan's Band, after a witch who is said to be their

patroness.] under a debt which they may find it troublesome to pay. Another

common tradition is that Ailsa Craig owes its origin to the Prince of

Darkness. That potentate has never taken to curling: [A Kilmarnock collier

on his way to the pit one morning got so alarmed at what he saw on a

curling-pond near the town that he rushed home and informed his wife that

"he had seen a sicht that would keep him from going farther that day; he had

seen Bryan o' the Sun Inn and the deil quitin (curling) on the auld water."

In the light of Ailsa traditions the juxtaposition of the two names is

suggestive. The collier's vision was satisfactorily explained. John Bryan,

landlord of the Sun Inn, a tall portly man and it keen curler, had got a

blacksmith to go and have a spiel with him at a very early hour. The

contrast between Boniface and Burn-the-wind, who was ''a wee, black, towsy,

ill-washed body," led the collier too readily to a wrong conclusion.] it has

generally been supposed that lie does not allow ice to be formed in his

dominion, and that he hates the channel-stage as his worst enemy. No

respectable curler mentions his name, nor is he; an initiated member of

any-affiliated club. What if, after all, the game be under his royal

patronage, and he be actually furnishing the world with curling-stones to

work out his wicked purposes! Let us away from these traditions, and breathe

the fresh air of geologic facts. But it is "out of the frying-pan into the

fire." "Ailsa Craig is the plug of the throat of a volcano," says our

petrologist in the next chapter. Can the roar of the Ailsa channel-stane

ever again then be "music dear to a curler's ear?" The ten thousand voices

which have carried the sound of the Craig to the ends of the earth have been

proclaiming Scotland's doom. This is the simple question:-

"Ailsa Craig is 370 Yards

high, 1300 yards long, 860 yards broad, and 2¼ miles in circumference—area,

220 acres. At the rate of 1000 pairs of curling-stone blocks per annum

(twelve blocks to a ton), how lone will it take to remove the Craig, clear

the throat of the volcano of which it is the plug, and overwhelm the

country?"

Enough of petrology and

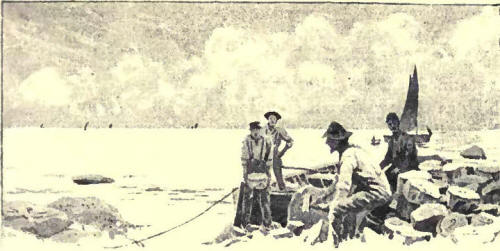

tradition. Let us begin with May 16, 1889, when, with Messrs Douglas and

Thor-burn, we visited Ailsa, and heard the rock tell its own story. The

Craig is rented from the Marquis of Ailsa by Andrew Girvan, who, for £30 a

year, has the pasturage of the island, and a monopoly of the supply of

stone. Under the charge of Andrew we left the town of Girvan, which is 9½

miles distant, and our boat drew up at the neat little jetty erected by the

Northern Lighthouse Commissioners, in connection with the lighthouse which

stands on a spit of level ground on the east side of the island. We found

James Millar waiting there to receive us. James, whose profile is accurately

given in the frontispiece of this chapter, is a man of great intelligence

and physical power. He is the blocker-general in the curling-stone world,

visiting Ailsa Craig for two or three months in the year, and then returning

to Ochiltree, of which place he is a. native, to prepare the Burnocks. The

majority of our curling-stones have come through the hands of James Millar.

There is a knack in blocking the stones, as there is in most other things,

and James has it. "You must have a good straight run in the boulder," says

he; and from what we saw it is not easy to get. Once James gets it he soon

divides up his subject into squares, leaving to one or two subordinates to

chip the squares into such roundness as they are seen to possess in our

drawings. ,latch-making among the Ailsa blocks is most difficult. Nature has

joined them together, but not in "happy pairs." It is under the hands of

James Millar that like is drawn to like. James is Mormon in his

match-making. When he Gets a block with some sweetness and regularity in its

disposition, he numbers it, say "38" or "39," as the case may be, and then

selects five, tell, or twenty companions for it, giving them all the same

number, to show their similarity, and leaving the pairing process to the

manufacturer. There are, as all curlers are aware, three kinds of Ailsas—the

Blue hone, the Red Hone, and what is called the Common Ailsa. The last, as

its name implies, is most plentiful. The Red is scarce, and getting scarcer

every year. At the time of our visit workmen were busy blasting a seam of

this variety on the north side of the island, about 200 feet above the sea.

One of the men, bound by a rope, descended the precipice, inserted a blast,

and was then pulled up. When the blast came off the dislodged stone was

dashed down on the shore and broken into fragments. It is the difficulty of

getting it that makes the Red Hone so dear. James Millar unhesitatingly

places the other varieties before it, and gives the Blue Hone the highest

place among the Ailsas. The prices of these blocks put on the rail at Girvan

run from 3s. 6d. to 9s. per pair, the highest price, of course, being paid

for the Red Hone. At a cost of about 10s. per ton, or about 2s. per pair,

the blocks are carried by railway to the principal manufactories in the west

country. In the workshop the block is first of all

cheesed,

i.e., chiselled into the shape of a gouda cheese. The stone is thereafter

bored. When it has been properly swung and balanced, it passes into the

hands of a workman with a teethed hammer, who gives it a rough finish all

round, and then rolls it off with a mould, and prepares it for the grinding

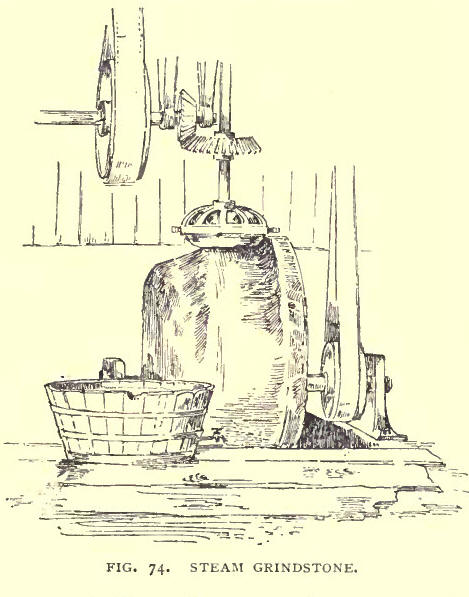

machine. The cost of this machine is about 120. It is in two parts. The

curling-stone, in a cup at the base of a vertical, is whirled round at great

speed by the upper belt operating on two meeter-screws, and held firmly on a

Nitshill grindstone driven in an opposite direction by the lower belt, as

shown in our drawing. The stone is reduced and roughly polished by this

process. In making the concave sole, the stone, instead of being allowed to

run in a hollow, is run upon a raised ridge—A, in the grindstone cheesed,

i.e., chiselled into the shape of a gouda cheese. The stone is thereafter

bored. When it has been properly swung and balanced, it passes into the

hands of a workman with a teethed hammer, who gives it a rough finish all

round, and then rolls it off with a mould, and prepares it for the grinding

machine. The cost of this machine is about 120. It is in two parts. The

curling-stone, in a cup at the base of a vertical, is whirled round at great

speed by the upper belt operating on two meeter-screws, and held firmly on a

Nitshill grindstone driven in an opposite direction by the lower belt, as

shown in our drawing. The stone is reduced and roughly polished by this

process. In making the concave sole, the stone, instead of being allowed to

run in a hollow, is run upon a raised ridge—A, in the grindstone

In

ordinary grinding, the stone, by means of In

ordinary grinding, the stone, by means of

a

lever which raises the cup, can be taken out, and another inserted without

stopping the machine. In grinding the concave sole both parts of the machine

are, however, slowed in case any injury should be done to the running; ride

of the stone—a matter of the greatest importance, for no stone can run

correctly when this delicate ridge is in any way impaired. On its removal

from the grinding machine the curling-stone, which is now quite respectable

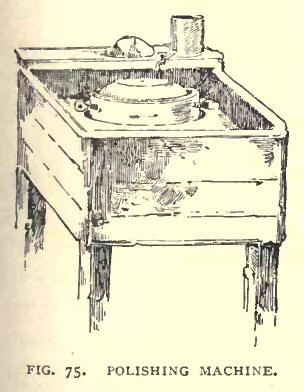

in appearance, is fixed in another cup set in a frame, as shewn in Fig. 75,

and is then driven round at tremendous speed by a belting which operates

underneath. The honing process is now begun; rough freestone, then

Crakesland stone, and finally Water of Ayr hone being successively applied

by the hand to both sides. To the one side or sole no more is now done. This

is the dull side. To the other side polishing putty is applied on flannel

held firmly on the heated stone by a wooden lever. This is the keen side.

Don't be impatient. The stone is not yet finished. A rough ridge runs round

the circumference, which must be reduced. With a diamond two zones are

drawn, and this ridge is chiselled into a neat belt. Neither under nor above

but upon this belt the channel-stane is destined to receive all its

"plagued-knocks." Now let us have an iron bolt, with a round or a square

head, and a screw on the other end to meet the screw of the handle, a

washer, and finally a handle none of your gew-gaws of ivory and silver, but

one of plain brass; not too much of a swan-neck, but rather square, with

heck and grip about the same thickness. We screw the handle firmly on the

bolt, having previously numbered their that the one may know the other and

give us no further trouble. With his chief equipment fully equipped, at a

cost of from 30s. to 50s., according to the material used, the curler may

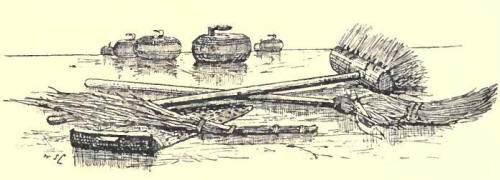

now take his place on the ice. Not, however, without a broom, and that

"neatly tied." Let him respect that old Dunblane rule. 'When the majority of

our curlers have provided themselves with housemaids' besoms, we may bring

these articles down upon its by condemning them. But duty compels us to do

so, and to urge young curlers to reform the present state of affairs by

universally adopting Scotland's air broom howe as their sweeping equipment.

There is character in a kowe; there is nationality about it. Let the curler

swear by the kowe. As to Russian valinki, roon shoes, rubber overshoes,

et hoc genus omne, we condemn them all as elephantine. No proper curler

requires them. Let him take care of his Dead, and his feet will take care of

themselves. We have always admired the hill lads of Largs, [Cairnie's Essay,

p. 52.] who could curl in their stocking-soles and never feel cold, and

"when at a push could mend the pace of a coming stone very dexterously by

plying before it with their Kilmarnock bonnets." These bonnets are the

orthodox head-bear of curlers. An indispensable equipment, according to the

majority of curlers, is a flask. Our counsel regarding it is given like that

of the dealer who exhorted his son to follow honesty as "the best policy,"

quietly adding, "I ha'e tried baith." A flask is useful, but not

indispensable. It is certainly dangerous to the feet if it affects the head.

It is possible to have too much even of "the auld kirk;" and whatever

latitude may be allowed to common players, every skip must take special care

to keep this equipment in its proper place. The best rink in the world must

lose the match when it conies to this:-- a

lever which raises the cup, can be taken out, and another inserted without

stopping the machine. In grinding the concave sole both parts of the machine

are, however, slowed in case any injury should be done to the running; ride

of the stone—a matter of the greatest importance, for no stone can run

correctly when this delicate ridge is in any way impaired. On its removal

from the grinding machine the curling-stone, which is now quite respectable

in appearance, is fixed in another cup set in a frame, as shewn in Fig. 75,

and is then driven round at tremendous speed by a belting which operates

underneath. The honing process is now begun; rough freestone, then

Crakesland stone, and finally Water of Ayr hone being successively applied

by the hand to both sides. To the one side or sole no more is now done. This

is the dull side. To the other side polishing putty is applied on flannel

held firmly on the heated stone by a wooden lever. This is the keen side.

Don't be impatient. The stone is not yet finished. A rough ridge runs round

the circumference, which must be reduced. With a diamond two zones are

drawn, and this ridge is chiselled into a neat belt. Neither under nor above

but upon this belt the channel-stane is destined to receive all its

"plagued-knocks." Now let us have an iron bolt, with a round or a square

head, and a screw on the other end to meet the screw of the handle, a

washer, and finally a handle none of your gew-gaws of ivory and silver, but

one of plain brass; not too much of a swan-neck, but rather square, with

heck and grip about the same thickness. We screw the handle firmly on the

bolt, having previously numbered their that the one may know the other and

give us no further trouble. With his chief equipment fully equipped, at a

cost of from 30s. to 50s., according to the material used, the curler may

now take his place on the ice. Not, however, without a broom, and that

"neatly tied." Let him respect that old Dunblane rule. 'When the majority of

our curlers have provided themselves with housemaids' besoms, we may bring

these articles down upon its by condemning them. But duty compels us to do

so, and to urge young curlers to reform the present state of affairs by

universally adopting Scotland's air broom howe as their sweeping equipment.

There is character in a kowe; there is nationality about it. Let the curler

swear by the kowe. As to Russian valinki, roon shoes, rubber overshoes,

et hoc genus omne, we condemn them all as elephantine. No proper curler

requires them. Let him take care of his Dead, and his feet will take care of

themselves. We have always admired the hill lads of Largs, [Cairnie's Essay,

p. 52.] who could curl in their stocking-soles and never feel cold, and

"when at a push could mend the pace of a coming stone very dexterously by

plying before it with their Kilmarnock bonnets." These bonnets are the

orthodox head-bear of curlers. An indispensable equipment, according to the

majority of curlers, is a flask. Our counsel regarding it is given like that

of the dealer who exhorted his son to follow honesty as "the best policy,"

quietly adding, "I ha'e tried baith." A flask is useful, but not

indispensable. It is certainly dangerous to the feet if it affects the head.

It is possible to have too much even of "the auld kirk;" and whatever

latitude may be allowed to common players, every skip must take special care

to keep this equipment in its proper place. The best rink in the world must

lose the match when it conies to this:--

Skip—What d'ye see o' this

ane [hic], Donald?

Donald-I see naethin o' 'er, whatever.

Skip—Aye, weel, then, Donald, my man, shist [hic] tak' what ye see o't.

(SECOND.)

Such equipments as we have

been describing are the property of the curler as an individual. Of those

which fall to be provided by the club the most important is, of course, the

curling pond. Where there is a subsoil of clay the formation of a pond is a

very simple matter. Where the subsoil is gravelly, a layer of clay at least

six inches thick must be prepared. Clubs will not expect us to give them

advice on this subject. They will get specifications from a practical

authority, and accept the estimate of a reliable contractor. Inverness, in

its funny Palladium, records some experiences which may be useful. Year

after Year a committee was "appointed to look out for a curling-pond." At

one meeting it was agreed "to provide an omnibus so that the committee might

enjoy a drive in the suburbs of the town for the ostensible purpose of

looking out for a suitable spot." Still nothing was done. One inventive

brother now came forward with "a scheme whereby ice of any thickness would

be had all the year round without puddling or asphalting." After sundry

discussions (not dry) it was found that the scheme "would not hold water,"

but the brother "was graciously permitted to continue his experiments at his

own expense." At last, by the determined effort of a fresh committee, a pond

was constructed, and opened with an imposing ceremonial.

"It may be remarked, in

passing," says Ye Palladium, "that the total expense of the completed pond

did not exceed by more than three tunes the original estimate. Another

committee had therefore to be appointed, with full powers, to devote all

their time, attention, and energies to waiting on all the members of the

club, and any other person or persons they think proper or improper, without

prejudice, for subscriptions to any amount."

If we had frost enough we

would condemn all kinds of cement or artificial ponds. They raise the price

of curling, and destroy the glorious roar of the channel-stane. With our

little frost they must, however, be accounted an enormous boon. Since

Cairnie's time great improvements have been made on these ponds. Every club

that can afford it has one, and with a silvering of ice a carne can be had

on the cement with the thermometer at 33°. Recently one or two clubs have

had the artificial pond so constructed as to be available for lawn tennis

when there is no frost. As in the case of the natural pond, the club with a

cement pond in view, will employ a good contractor, and see that the expense

does not overrun the estimates. Special care should be taken that the pond

is laid down east and west, and in a situation sheltered from the rays of

the sun. The making of the pond is not the difficulty; it is the upholding

of it. These ponds are all liable to crack, and the filling up of their

cracks is troublesome. The Edinburgh Northern Club has improved the

usefulness of the artificial pond by fitting up the electric light, thus

enabling many who could not otherwise do so to enjoy the game. The Coates

Club has done the same, and others are likely soon to follow suit.

In the arrangement of the

curling-house, which ought to adjoin the pond, the club must chiefly

consider the comfort of the stones. Everything here should be kept neat and

clean. Order in the curling-house is a proof that the club is well managed,

and it conduces to order on the ice. Without a little stove, and a good

press to store away a few needful and valuable articles (the nature of which

we do not require to indicate), no well-regulated curling club should look

upon its curling-house as complete. The house and the pond ought to be under

the charge of a keeper or officer who has some force of character, and who

can take a turn at the game when required. Where a competent officer is

responsible, no club will have to suffer, as the Spott Club once had, by

malicious persons destroying the ice. The plan adopted by that club was

rather original. They advertised as follows:-

"SPOTT CURLING CLUB.—Wanted

immediately, a man accustomed to the use of firearms to watch the

curling-pond during frost. He will be provided with good accommodation,

including use of stove, &c., in the pond-house. For further particulars,

apply by letter, stating wades expected, to the Hon. Sec.—Dunbar, Feb. 27,

1873."

Among applications from

gamekeepers and other "great guns" there was the following:-

"Deer Sir, i Am a man who wil

wach yer pound at ane shiling the nite fur frost. A can shut an forearms in

the house write the John Grubb at Mrs Firds at Linton."

Without John's services, the

evil-doers were paralysed with terror, and the Spott Club got their pond

cheaply protected for the rest of the season.

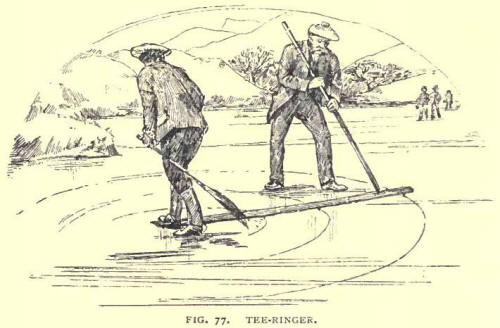

One of the most useful

ice-implements is the Tee-ringer, invented by Mr Palmer of Currie. By means

of it, broughs, hog score, and sweeping score can all be drawn with accuracy

in a. very short time. The Foothold of the Canadian curler is the Hack in

the ice, and in Lanarkshire and some

other districts of Scotland

this is still used. The majority of our clubs, however, are now supplied

with an improved form of Cairnie's Foot-iron (aide p. 159), a fillet of hard

wood being fitted at the back end, bevelled so as to keep the player's

centre of gravity within the outline of the crampit. A folding form of

crampit has recently been patented by Duncan Cameron, Aberfeldy. This

gentleman has also invented a snow-cleaner, which receives high commendation

from the Marquis of Breadalbane, who says that one man can with it do as

much work as six can do in cleaning a pond by the ordinary methods. Its cost

is £3, 1Ss. If some machine of a light description could only be invented to

clear away snow- when the ice is too weak to allow of any person vvorking

upon it, this, we have often thought, would be of great benefit to clubs.

The Kilwinning Curling Club, when they met to play Dairy on the water of

Garnock, in the year 1801, found that no form of spade or snaw-shool could

be got without much delay. "Look here," said one of their number— J. C. "I

tell you what to do. Here is my grey plaid. I'll roll myself in it: I am six

feet. Two of you will take the one end and two the other, and draw me

broadside the length of the rink up and down, and you wiII soon clear the

ice." This was done; the rink was effectively cleared, and J. C. was none

the worse. [J. C. died in 1841, act. 84. Vide Annual 1843, p. 134.] It would

not be safe for any club to depend on such chivalry in our days, so they had

better mind their snaw--shools. The Rev. Dr Somerville of Currie invented an

instrument, which lie called The Justice, for measuring disputed shots. it

is simply a big pair of iron-shod compasses, one leg to be fixed in the

toe-see (vide p. 155), and the other to be adjusted so as to determine the

nearest stone. It is a good thing of its kind. The same gentleman invented

The Counter, for indicating the state of the game on a pillar before the

eyes of the players. A better way of recording matches is for a club to have

a. supply of such scoring-books as can be had from Carswell, Paisley, or

Fair grieve, Edinburgh. [Curlers should keep their scores and records of

their matches—if they are worth keeping. A well-known skip, Peter Shaw, has

shewn us his rink record-180-1886. Matches played with other clubs, 68;

won,: 3 drawn, 3 ; lost, 12; shots up, 93; shots clown, 34; net majority,

593. This is what we call "worth keeping."]

One word as to the vivres-equipments, on

which the enjoyment of curling so much depends. In the little matches made

up on the ice from day to day—scrub games, as the Canadians call them—each

curler may look after himself; but on medal days the members of a club

should see what their secretary can do in providing for them. A bonspiel

between rival parishes is a good occasion for the chief nobleman of the

district to renew his patent of nobility. Many take advantage of it, and

spew hospitality to the curlers. When no baronial mansion smiles upon the

scene, the club on whose ice the match is played must entertain the other,

and that right well, as becometh curlers. On neutral ice for a "Royal"

medal, if the two clubs have no common vivres forward, for any sake let them

remember the umpire. It would be cruel to give navies, but the worst account

of a curling match on record is this—found in one of our Annuals:-

"The umpire got neither meat nor drink during

the match, and a very cold day it was."

That must never occur again. A plate of Irish

stew will satisfy an umpire or any other man. There is no "equipment" to

match it among curling-vivres. Sure and a black strap " of Dublin will (10

your honour no harm. If this is too much of "Ould Ireland," a bottle of Old

Edinburgh for the Scot, or one of Trinity Audit for the Sassenach, will

safeguard his nationality. "Beef and greens," as from time immemorial, must

be the feast of brotherhood when the day is over, and every innovation must

be resisted to the death which interferes with "curlers' fare." In "beaded

Usqueba with sugar dash'd," let them also, as long as curling lasts, pledge

their loyalty to each other and to "auld ling syne."

|