|

Now mony a club, jocose and

free,

(xi'e a' to merriment and glee;

Wi' sang and glass, they fley the pow'r

O' care, that wad harass the hour."

Robert Ferguson.

Then to the inn they a'

repair,

To feast on curlers' hamely fare—

On beef and greens and haggis rare,

And spend the nicht wi' glee, O!

And there owre tumblers twa or

three,

Brewed o' the best o' barley bree,

They sing and jest while moments flee,

Around that social tee, O!"

T. S. Aitchison.

"True feelings waken in their

hearts

And thrill frae heart to han'

O peerless game that feeds the flame

O' fellowship in man!"

Rev. T. Rain.

The Pillars o' the

Bonspiel—Rivalry and Good Fellowship."

Old Toast.

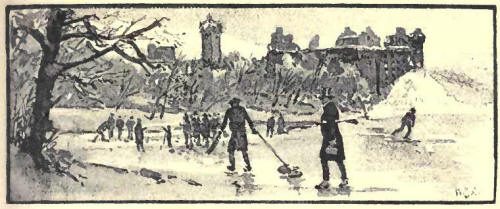

URLING—the

game of rivalry and good-fellowship—has naturally made great progress by the

institution of societies or clubs. (The word club occurs very rarely

in the records of last century. Excepting Dunfermline and Duddingston, the

designation invariably used is Society.) The principle of association could

not readily be taken advantage of in troublous times, and it is not till the

eighteenth century that we find it used for the development of the game.

Societies were then formed in those districts where it had been previously

popular. Curlers in such districts were prepared to appreciate the advantage

of societies in promoting social fellowship and scientific skill. Experience

also fitted them to frame such conditions of membership as would best secure

these ends. It is with the written records of the early curling societies we

have now to deal in the tracing the history of the national game. URLING—the

game of rivalry and good-fellowship—has naturally made great progress by the

institution of societies or clubs. (The word club occurs very rarely

in the records of last century. Excepting Dunfermline and Duddingston, the

designation invariably used is Society.) The principle of association could

not readily be taken advantage of in troublous times, and it is not till the

eighteenth century that we find it used for the development of the game.

Societies were then formed in those districts where it had been previously

popular. Curlers in such districts were prepared to appreciate the advantage

of societies in promoting social fellowship and scientific skill. Experience

also fitted them to frame such conditions of membership as would best secure

these ends. It is with the written records of the early curling societies we

have now to deal in the tracing the history of the national game.

The dividing line which we

have already drawn between ancient and modern curling, forces us also in

this chapter to confine our attention to the records of such societies as

existed in the last century. Curling societies which claim to be ancient,

but whose records go no further back than the present century, must not

expect from us more than a passing notice. This is the only course open when

we wish to tread the sure ground of history. As illustrative cases we may

give Linlithgow and Lochleven, where, as we have already said, there are

traces and traditions as to curling " from time immemorial." That a club

existed at the former place in the last century may be gathered from a

chance entry which we have discovered in the minute-book of the Dunfermline

Club, where the sederunt of the annual meeting in the house of James Cupar,

2nd February, 1792, includes:-

"Mr John Gibson, a visiting

brother from Linlithgow Club."

John Gibson and his brother

members at Linlithgow do not appear to have written down their doings, and

by their negligence we have lost a good deal, for curling at Linlithgow in

Gibson's day must have been carried on in the light of long experience. In

the case of Lochleven, the members of the Kinross Club, as faithful

guardians of its curling fame, after a careful inquiry by Sheriff Skelton

and a committee in 1818, decided to carry the existence of a curling society

there as far back as 1668. That there was curling on Lochleven long before

that need not be doubted, and that the Kinross Club deserves highest honour

for the careful preservation of the traditional mysteries of the game will

be apparent when these come to be considered ; but the want of written

records prior to the year 1818 leaves us, as in the case of Linlithgow,

without that information as to the early game on Lochleven, which would here

have been of the greatest interest.

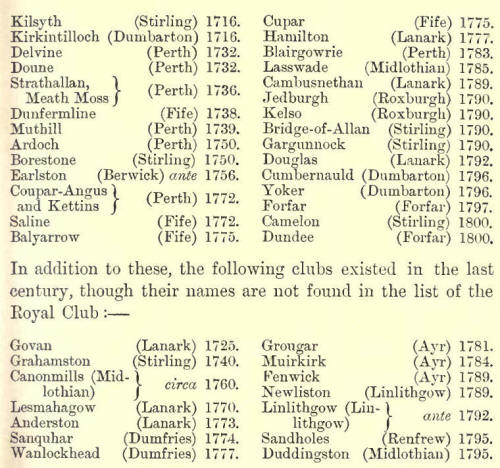

On the present list of the

Royal Caledonian Club we have twenty-eight affiliated clubs entitled to

attention as having been formed in the eighteenth century. We give them in

the order of their institution, with the counties to which they belong, as

it is of importance to note the geographical area of ancient curling.

Of the forty-two societies

thus enumerated, only ten possess written records of the last century, and

in a few cases these do not extend back to the dates at which the societies

are said to have been formed. Through the kindness of the various

secretaries, all the available records have been placed in our hands, and we

have perused them "at some expense of eyesight, and with no small exertion

of patience." In what follows we have tried, as far as possible, to make the

different minute-books speak for themselves, and tell us what they know

about the manners and customs of eighteenth-century curlers and curling

clubs.

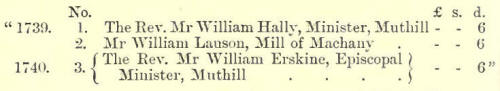

MUTHILL (1739).—The honour of

possessing the most ancient records falls to Muthill. It is awarded,

however, with some hesitation, for the minute-book of the Muthill Society,

though a neat and interesting record, is evidently not so old as the society

itself. At a general meeting of the society, held in the house of John

Bennet, vintner, on 14th January, 1823, [There had been no ice in the two

previous years, 1821 and 1822.] there was:-

"Voted to William Gentle,

clerk, for Looks and drawing out Records and Laws of this society since its

formation as contained in this book, £1 5s."

The minutes are, therefore,

William Gentle's work. This is borne out by the first set of rules entered

in the volume, which bears to have been revised in 1820 and 1821 1 ; but it

is evident that William Gentle had documents in his hands which were written

at the formation of the society, and that other parts of the volume are

transcribed from these. The antiquity of the records may thus be allowed to

pass. The list of members of the society, as "constitute in the year 1739,"

begins thus:—

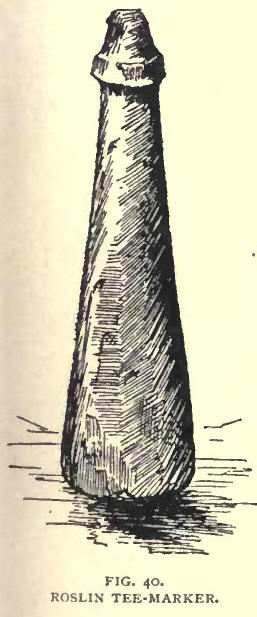

At first the society was not

a large one, and Mr Rally seems to have been its leading spirit. [A drawing

of the stone supposed to have been used by Mr Halle is i given at p. 40. The

parishioners of Muthill were so opposed to Mr Hally at I his ordination in

1704 that they refused to allow the Presbytery to enter the church ; but he

was afterwards much esteemed by their for his good qualities. He died in

1754. Dr Rankin, his able successor, informs us that "Mr Hally was a xnan of

great physical strength, and a good wrestler] as well as curler and

preacher."] By the end of the century, however, we find that 187 members had

been enrolled. A kindly custom on the part of the brethren was to allow

members of other societies to "initiate" into Muthill Society for 3d., being

half the annual fee of ordinary members. Since they are the most ancient

regulations that have come down to us, we may here give the:-

"RULES AND STATUTES to be

observed by the SOCIETY OF CURLERS in MUTHILL,

November the 17th, 1739.

1. That each Member shall

attend the Precess of any Quorum of the Society when called, unless they

have a reasonable excuse, under the penalty of Six Shillings Scots.

2. That no match of curling

shall be taken up with another Parish untill five of the Members of the

Society be previously acquainted therewith, and those that shall be chosen

to play in any such match are not to absent themselves therefrom, under the

penalty of Five Shillings Sterling, and being extruded the Society till

payment.

3. That the annual election

of all the officers of the Society shall be upon the first Tuesday of

-------

4. That there shall be no

wagers, cursing or swearing, during the time of game, under the penalty of

Two Shillings Scots for each oath, and the fines for by wagers to be at the

discretion of the Precess and the other members present, and the wagers in

themselves void and null.

5. That every residing Member

of the Society betwixt and the next annual election shall provide himself in

a curling stone, to be kept in this place under the penalty of One Shilling

Sterling.

6. That all the money

received by the Society for the entry of new Members or Fynes be kept for

the use of the Society in general.

7. That every Member shall

pay yearly to the Treasurer Four Shillings Scots, for the use foresaid.

8. That after this date at

taking up any matches betwixt any two parties they are only to have choice

about.

9. That there shall be no

addition or alteration made of the above Rules but at the yearly meetings.

And its recommended to the

Society in general to provide four right leading stones to be equally

divided in all matches, etc., etc., and the Committee to draw up the men for

the match."

There is little information

in these as to the manner of playing the game at Muthill in ancient times,

and we have no record in the old minutes of any bonspiel, but sundry charges

for carting stones imply that the society had frequent matches with Ardoch,

Monzie, and other parishes. Under date February 7, 1789, we have this

curious entry:

"To Isabel White for whiskey

for cleaning the ice, £0 1s. 8d."

How the whisky was applied to

such a useful purpose the minutes do not state. At the annual meeting,

December 26, 1789, it was agreed:

"That every stone handed or

mended at the expence of the box is common to all the brethren, or them who

puts on more than one stone if they shall choose to hold it up shall have

liberty to do with it as they please."

Drawings of some of these old

stones may be seen at p. 46. One stone sufficed for each player, but the

records state nothing about the rinks, or the numbers composing them. It is

interesting to notice the prohibition of wagering, cursing, and swearing

(Rule 4). Such a rule is common to most of the old societies, and it shows

how jealously the early players protected the reputation of the game, and

how anxious they were to exalt its position.

CANONMILLS (1760).—Ramsay,

when writing his account of curling in 1811, and referring to the tradition

regarding the Town Council's patronage of the game (vide p. 91) in the

beginning of last century, says:-

"Then it was practised

chiefly on the North Loch, before it was drained, and at Canonmills. At

which latter place a society was formed about fifty years ago, and continued

to flourish a considerable time. Of late, however, it has dwindled away to

nothing."

We have Given illustrations

(p. C4) of stones of the earlier circular type which are supposed to have

belonged to this club, but no trace can be found of any written records of

its transactions. Certain sons composed for the club were, however, printed

in a small volume [Songs for the Curling Club held at Canonmills. By a

Member. Ediu. Printed by J. Robertson, 39 South Bridge.] in 1792, and as

some of these appear to have been written soon after its formation, they

entitle it to notice here. These songs are more interesting than dry

minutes, and give us useful information as to the words in use at the game,

and as to the social habits of the players.

"The CanonmilIs Loch," says

Captain Macuair, [Preface to Curling, Ye Glorious Pastime, an excellent

reprint of the Account of Curling by Ramsay, and the Canoninills Songs, in

one volume, published in 1882.] "on which the members of the club were wont

to assemble, has long since disappeared, having been drained and built over

many years ago. In his plan of the city of Edinburgh and its vicinity,

published in 1837, Hunter places it in the angle formed by the junction of

the roads leading down from Bellevue Crescent and Eyre Place, adjoining the

wound occupied by the Gymnasium, but better known in those days as `the

Meadow.'"

This situation must have been

very convenient for Edinburgh curlers when deprived of the use of the Nor'

Loch for their favourite sport, and in those days of clubs, they would

naturally form themselves into a company that they might more effectually

enjoy the game and its attendant socialities. III many respects Canonmills

was better suited than Duddingston Loch for the townsmen, and we are not

surprised to find in one of the minutes of the Duddingston Club (8th

December, 1824) this entry:-

"The meeting thought that a

piece of ground night be obtained about Canonmills, which might be

occasionally- used, as more convenient for many members than Duddingston."

As regards the membership we

are left to conjecture---

we have not even the name of

the author or authors of the songs; but while it existed the club could not

fail to be an important one, and as the song set to the March of the

magistrates comes first in the collection, it is probable that the patronage

of the Town Council was bestowed on the Canonmills curlers. The songs are

such as could not fail to be appreciated by citizens of wit and learning who

inclined to unbend the bow at the curlers' feasts, and they are full of that

enthusiasm which always animates the votaries of the game. The Curlers March

is succeeded by The Blast, which calls upon the brethren, now that Phoebus

has wandered south, to rear the "groom standard," for it is only fools that

dread the wintry death of Nature: curlers smile at such fears:-

"As we mark our gog,

And measure off our hog,

To sport on her cold grave stone."

We are next favoured with a

song in which the singer [Sir Richard Broun has, among the notes prepared

for a second edit on of his Memorabilia, which never "came off," appended

the name of Dr 13airnsfather to this song—on what authority we know not. The

title implies that the songs are by one author, but the internal evidence is

against this.] pokes fun alike at the pride of the city and the antiquity of

the national game, and it is easy to imagine the hilarious mirth with which

the Canonmills curlers would receive this account of:

THE ORIGIN OF EDINBURGH

CASTLE.

Tune—"AULD LANG SYNE."

I. "On Calton-Hill and Aurthur-Seat,

Great Boreas plac'd his feet,

And hurled like a curling-stane

The Castle wast the street.

"But that was lang syne, dear sir,

That was lang syne,

Whan curling was in infancy,

An' stanes war no fine.

II. "An' lest it should be

mov'd or stole,

(Tho' strange it seems to tell),

The handle loos'd, and left the hole

`which now serves for a well.

"But that was lang syne, dear sir,

That was lang syne,

Whan curling was in infancy,

An' handles no fine.

III. "Next, as a hint lie

meant a fort,

Which Northerns might defend,

He like a flag-staff praped up,

His bosom shaft on end.

"But that was lang syne, dear sir,

That was lang syne,

Whan curling was in infancy,

And besoms no fine.

IV. " Wha, thinks it's fase

that we alledge,

May carefu' search the hole

If he finds not the handle-wedge,

He then may doubt the whole.

"For 'twas there lang syne, clear sir,

'Twas there lang syne;

An' what needs fo'k dispute about

What happened lang syne."

The song which follows this

humorous sally is a melancholy one, and bemoans the long absence of frost:-

I. "I've mony winter seen an'

spring,

But like o' this did I ne'er see—

Three open winters in a string—

An' may the like again ne'er be.

Chorus--"Alake my walie

curling-stanes

Ha'e no' been been budged thir winters three

'Tween the rain's plish-plash an' a fireside's fash

They have dreary winters been to me.

* * * * *

V. "When I on former winters

think

How on the ice we met wi' glee,

And cheerfu' swat to clear a rink,

It gars inc sigh right heavylie.

"Alake, &c.

VI. "When we had mark'd our

gob an' hog,

And parties form'd o' four or three, [*]

Ilk ane wi' crampits an' broom scrog,

How anxious yet how blythe played we.

"Alake, &c.

VII. "When we had keenly

played a while,

Brose comes, an' whisky, cawld to flee,

We Sol and Boreas to beguile,

'Tween shots wi' spoon or glass make free.

"Alake, &c.

VIII. "When anes our game or

light was done,

We marched to dinner merrylie,

Wi' saul an' body baith in tune,

Wba shu'd be blythcst a' our plea.

"Alake, &c.

[*] This seems to imply that

the number on a rink was less than in other clubs of the early times.

IX. " When comes the bowl we

drink an' sing,

An' crack o' bonspales till ha' free,

Syne part in peace—a happy thing;

Sic times again I fain wad see.

"Alake, &c.

X. "May Boreas hasten frae the

north,

Gi' silver lokes to bush and tree;

I`d rather he wad plank the Forth

Than Thetis ever on us be.

"Alake, &c."

The lament over Three Open.

Winters is followed by The Welcome Hame, sung to the chorus:-

"There's nae luck about the

house,

There's nae luck at a' ;

What luck can winter days produce

Whan curlers are awa'."

Now that the loch is bearing,

the "deam" is ordered to set her wheel aside and put the house in order; to

"ram the chimley fu'," and "get on the muekle pat," while "mine host"

himself hastens to the "bot" and wails a "breast" to make fat brose for the

curlers, who will readily be recognised as "kin" to the moderns by this

touch of nature-

"Gae, ladie, seek their

crampits out,

For they will a' be here

To get a dram, without a doubt,

Afore the ice be clear."

When everything has been set

in order against their coming—the "substancials" ready, the "muckle room

dusted, and the tables placed—the anxious host breathes a sigh of relief, as

well he might.

"Hech, now I think the warst

o'ts o'er,

Sae they may come their Wa'

May this frost staun thir fortnights four,

Gar beef and whisky fa'."

In the last song of this

ancient and interesting collection, the praises of the game as a

health-giving, innocent, and social amusement are quaintly set forth, and it

would be difficult to find among the thousands of poetical panegyrics of

this century anything better than The Choise of the old Canonmills Club.

This curlers' weather is, I

trow -

O weels me on the clinking o't;

Fo'k may good ale and whisky brew,

Well line fun at the drinking o't.

For now we'll meet upon the ice,

Air.' in the e'enin ; blythly splice,

To drink an' feast on a' that's nice,

My heart loops light wi' thinking o't.

By Boreas bund in icy chain,

Fu' weel we loo the linking o't,

Nor xish't to be soon loos'd again,

But rather fear the shrinking o't.

United by his potent hand,

In gleesom friendly social band,

We eith obey his high command,

Nor ever think o' slinking o't.

"The lover Boats on Menie's

eye,

His Iife lies in the blinkincr o't,

For if it's languid he maven (lie,

He canno' bear the winking o't.

But curlers wi' unfettered souls,

That ane another's cares controuls,

On ice conveen like winter fowls,

An' please them wi' the rinking o't.

"The sportsman may poor

rnawkin trace

Thro' snaw, tir'd -,ci' the sinking o't

Or if his bray-hound gi' her chase,

He's charmed ivi' the jinking o't.

But curlers chase upon the rink,

An' learn dead stanes wi' art to jink

When tir'd wi' that, gae in an' drink,

An' please them wi' the skinking o't."

COUPAR-ANGUS AND KETTINS

(1772).—The record-book (as it is entitled) of this club begins rather

abruptly with a genuine sheet of antique writing, which informs us that—

"The silver medal or curling

ston was challanged, played for and gained by the following persons in

Bendochie and Blairgowrie."

Eight names follow, and as a

ninth there conies that of Isack Low, "the brandey or oversman." This is the

first designation of a skip which we have found in the old records. The rink

evidently consisted of nine men. David Campbell was "brandey or oversman" in

the losing (Coupar) team, which also included nine names. The victors on

this occasion were challenged by the parishes of "Alith and Rattray," and

were beaten on 14th February, 1772. The following challenge is then issued

from Coupar-Angus, 11th January, 1774:-

"I take the Liberty to

address your as the Head of a Partie of Curlers who chalanged our silver

medall or Curling Stone upon the 14th Feby. 1772, when you were fortunate

enough to wine it from the united Pairishes of Blairgowrie and Bendochie,

then the Holders of the medall. In hopes of your having complied with the

terms contain'd in the 7th Article of our Table of Regulations, upon which

this medal! can and only can be play'd for by this Society, I hereby am

impowered to signifie to you a resolution of our meeting you and the other

curlers in the Pairishes of Alyth and Ratrey, upon Saturday the 15th

current, by nine o'clock forenoon, leaveing you to fix the place anywhere in

our Pairishes, in order to do our best to regain our medall. Your answer is

expected on Thursday by twelve o'clock."

This challenge was accepted

and the match played, at Welton of Palbroaie, on 22nd January, 1774, Peter

Constable being "brandey" for Coupar, with seven other players on his rink,

against Charles Rae and seven players of Alyth and Rattray. The latter were

victorious, and thus retained the medal.

In the Annual of 1843, p.

122, we are informed that the silver medal thus competed for from 1772 to

the end of the eighteenth century was the gift of Colonel Hallyburton of

Pitcur, and that it resembled "an old-fashioned iron crusie." The winners of

it attached each year a silver plate to the "medal" recording their victory;

but when Coupar was victorious nothing was added, so that these plates

recorded the defeats of the society in place of heralding its victories. In

1836 a fine of one guinea was imposed on David Davidson for having lost the

ancient trophy, but it does not appear from the minutes that the fine was

ever paid or the trophy recovered.

The articles of this society,

like those of Muthill, give little or no light regarding the method of

playing the game. They provide for the annual election of a president with

"the powers which commonly belonged to the presidents of other courts," and

a clerk, whose duty is "to keep a book containing the regulations of the

society, a list of the members, and such transactions as they shall judge

proper to be recorded." There were no other offices, the brandeys or

oversmen in matches being elected for the occasion. Each member was taken

bound under a penalty of ten shillings sterling to supply two "proper

curling-stones" within a year after his admission, and (Rule 7).

"He is likewise to take care

never to appear on the ice with a design of playing without being furnished

with a sufficient broom, under such a. penalty as the first Curling Court

having received information shall think proper to inflict."

If a member left the parish

his stones became the property of the club; and in matches he was not to he

accepted as an antagonist after his removal "out of the Parishes of Coupar

or Ketins." The fine for not providing stones seems to have been rigidly-

enforced, and many " brothers " suffered for their neglect. It was quite out

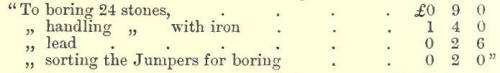

of proportion to the value of stones in these days, as this is given in the

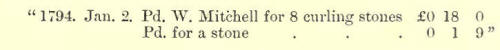

following items of expenditure :—

The articles of this old

club, like those of Muthill, impose certain fines upon their unruly and

gambling members. It is enacted:-

"Rule 14. That if any brother

in the course of play, or at society meetings, shall be guilty of swearing

or giving bad names to any member, he shall pay two pence for the first

offence, and be at the mercy of the court for repeated acts of said crimes.

"Rule 15. That no brother

shall engage to play with an other brother in this society for above the

value of one shilling sterling for one game, under the penalty of five

shillings, to be paid in to the Clerk of the Court."

Few offences against these

moral laws are recorded in the old minutes, but that such offences were not

uncommon in the end of the century is evident from the following entries in

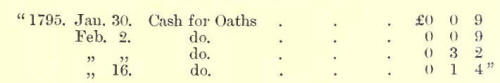

the treasurer's account :—

In one case, occurring some

twelve years before this, the cash was not received without some trouble, as

these extracts skew:-

"Coupar-Angus, 30th December

1783.

"At a meeting of the Curling

Society held here this day—Jno. Bett, Esq., Preses, and James Campbell, junr.,

Clerk—it was reported by some of the members that Jno. Crockett, one of the

members, was this day on the ice curling, and had been guilty of swearing

several tunes, also had lost one sixpence at play, therefor he should be

culled to court and make payment of the usual fines in like cases ; that

after being several times sent for to appear for the above crimes and make

payment of the fines, and never appearing, a part- of the members,

consisting of Chas. Ducatt, Jno. Edward, Jno. Bruce, and Alex. Henderson,

was accordingly sent to bring him; and after having ;one to his house and

asked him to come, he presented a gunn to them, and swore that be would

shoot the first person who should attempt to lay-hands on him, and struck

Chas. Ducatt on the breast.

"The Preses, considering the

conduct of the above Jno. Crockett, hereby dismisses him front being a

member of this society, and hereby secludes and debarrs any of the members

from hereafter curling upon the ice with him until he shall in a full

meeting hereafter acknowledge his faults, and make such compensation to the

society as they shall think the nature of the crime above requires, and

appoint the members present to intimate the above resolution to their absent

brethren.

"(Signed) Jno Bett."

"Coupar-Angus, 12th January

1786.

"The within-designed Jno.

Crockett appeared before the meeting, and made full and ample satisfaction

to them for the faults he committed against their rules ; therefore they, in

consideration thereof, hereby admit him again as their brother, to enjoy the

haill priviledges of a member of this society as formerly.

"(Signed) CHAS. DUCATT."

On the ex-pede-Hereulem

principle, the curlers of Coupar and Kettins, accustomed to use such stones

as we have before described (Ch. II. p. 42), must have been men of great

strength : it was creditable to themselves, and fortunate for their

offending brother, that they did not "sit upon " him more heavily.

SANQUHAR.—The minutes of this

club carry us back to the year 1774, when the society was formed, and with

the exception of blanks between 1809-17, 1819-1829, and 1832-1841, they

contain a careful record of the doings of the society for the long period of

one hundred years. They supply us with more information as to the ancient

game than any we have previously noticed, and as this information has for

some time been available in a little volume which holds a worthy place in

the literature of curling, [History of the Sanquhar Curling Society. By

James Brown, Secretary. Published on the occasion of the centenary of the

society, 21st January, 1874.] Sanquhar has hitherto held an advantage over

the clubs of the last century, and has been better known than most of its

contemporaries. The first minute runs thus:--

"Sanquhar, 21st January 1774.

This day the married and

unmarried men in this parish had an engagement at curling upon Sanquhar

Loch, twenty-seven on each side. The unmarried men gained the victory in

both dinner and drink. In the evening they dined all together at the Duke of

Queensberry's Arms in Sanquhar. After dinner it was proposed and agreed to,

that they should form themselves into a society under the name of the

Sanquhar Society of Curlers, and that a master should be chosen annually,

with several other regulations. Accordingly one of the oldest curlers

present being chosen preses appointed a committee of the best qualifyed to

examine and try all the rest concerning the curler word and grip. Those who

pretended to have them, and were found defective, were fined, and those who

were ignorant, and made no pretentious, were instructed. John Wilson,

Schoolmaster in Sanquhar, was chosen clerk to the society, and Mr Alexander

Broadfoot in Southmains, was chosen master for the present year. The terms

and prices of admission into the society were submission and obedience to

the master, discretion and civility to all the members of the society, and

secrecy. Fourpence sterling to be paid by every one in the parish, and

sixpence sterling to be paid by every one without the parish at their

admission. And liberty was granted to the clerk and some other members to

add what new members, where (sic), and to report them to the society at

their next election of a master."

The Freemasonry of ancient

curling is here for the first time clearly indicated, but we still look in

vain for rules by which curlers were then guided at play. They seem to have

been very chary of committing these to writing—perhaps they had no hard and

fast rules by which they could act. The omission is at any rate a noticeable

feature in all the older records. The Sanquhar Society had, however, a

system of organisation worthy of notice. On the 16th January, 1776,

according to their second minute,

"The society agreed to form

themselves into six rinks of eight players each, and to appoint some of

their number as commanders over them, these six rinks to be kept up as a

standing veteran army: and also to have some of those that remained over

above these six rinks as a corps-de-reserve with a proper commander over

then. Into this seventh rink or corps-de-reserve the young men are first to

be admitted, to be preferred to the veteran rinks as their merit deserves

and occasion requires. These rinks are to be called after the names of their

respective commanders."

It was the duty of the

commander of the youths' rink to instruct those under him in the art of the

game, and we believe this kindly interest in the initiation of the young is

still kept up in Sanquhar and surrounding districts. It is a custom, we

fear, "more honoured in the breach than in the observance," but Sanquhar

deserves honour from all who love the game for instituting it. With such

excellent organisation we are not surprised to find that the members of the

Sanquhar Society entered into the game with enthusiasm, and enjoyed the

social intercourse which pleasant matches with other parishes brought about.

"In former times," says Mr

Brown (p. 12), "the periodical bonspiels that took place between parishes

were the source of much pleasure apart from the game itself. In these days

there was little intercommunication, particularly- in winter, in country

districts. Every little country town was shut up as it were in itself, and

out from the rest of the world, social intercourse being confined to the

inhabitants of the place. A spiel between two parishes, therefore, was

looked forward to with much interest as affording the opportunity of seeing

new faces, gathering up some scraps of news, and forming new friendships.

They were the subject of much joyful anticipation, and great preparations

were made for its advent. So great was the flurry and excitement into which

the curlers were thrown that a certain scab used to say of Crawick Mill,

then a spirited and happy little place, 'It was an unto nicht in Crawick

Mill. They were running wi' teapots and razors the haill nicht."'

Among the regulations of this

old society there are only two which may be quoted as interesting:-

"Article V.—The masters are

to give due warning to the players at all times when any game is to be

played either among the rinks, or with a different parish, and in case of

neglect to be liable to pay the sum of One Shilling: and any player so

warned either refusing to come forward, or not giving a plausible reason for

his non-attendance, shall forfeit the sum of Sixpence. The masters are to

have the principal charge of their respective rinks, assisted by such of

their own rinks as they shall appoint, not exceeding two, and every player

is to submit 'without murmur, complaint or reluctance, to the master's

judgment, or those nominated by him. The masters are to use their endeavour

to suppress swearing or abusive language on the ice among their players, and

every person offending shall be fined of a sum not exceeding Twopence.

"Article IX.—At any play

among the rinks the reckoning not to exceed Sixpence each player."

In the former of these

"articles" the right of a master or skip to appoint two assistants on his

rink, and his responsibility for the good behaviour of his players are

worthy of notice. Regarding the latter Mr Brown in his History (p. 19)

writes:

"The ninth Article, dealing

with the subject of `reckonings,' points to a custom prevalent at one time

of meeting in the evening at the end of an important play, such as the

playing for the Parish Medal, in a social capacity. In connection with

inter-parochial games, again, this social entertainment took the form of a

dinner with a liberal supply of toddy. These `dinners and drinks,' as they

were called, were for long the stake played for between parishes, and were

grand affairs, the ticket being Five Shillings. This is a rather startling

figure, as money went in those days, and considering that the members of the

societies were, for the most part working men. Still it was so, and it came

to be regarded as a point of honour with every curler to attend these

dinners. Many were reduced to the direst shifts; frequently borrowing had to

be resorted to by way of concealing their poverty from all but the lender..

. . The practice of playing for dinner and drink appears to have prevailed

more or less down to 1830, when at the annual meeting of that year a

resolution was passed on the motion of Mr Hislop, weaver:—`That at all

parish spiels there should be no dinners, which being put to the vote, it

was agreed that dinners should be done away with in a general way, but that

any remember or rink may dine with the challenging party if they agree to

it."'

The two brief notes that here

follow prove that the ancient curlers of Sanquhar were not behind their

brethren at Coupar in the exercise of charity towards offenders:-

"Jany, 1782.

"Walter M'Turk, surgeon, was

expelled the society for offering a gross insult in calling them a parcel of

d-----d scoundrels."

"17th Dec. 1788.

The meeting proceeded to

chose officers for the ensuing year, when Mr Walter M'Turk, surgeon, was

chosen Preses."

Besides covering a multitude

of sins, the charity of the old curlers of Sanquhar soothed the sorrows of

those to whom the frosty season brought misery, when it brought happiness to

the curler's heart. Games were played for oatmeal and for coals to be

distributed among the poor, and this laudable practice is kept up in the

district to this day. Long may it continue: In many parts of the country the

same custom has for a long time prevailed. It is one of the brightest and

best features in the history of our national game, and if it should happily

become universal, curling shall then take even a higher place than it does

now as "a sweetener of life and solder of society."

HAMILTON (1777).—The

minute-book of the old curling club of Hamilton—a neat octavo—begins with

this manifesto:-

"We, Subscribers—curlers in

Hamilton, considering that the lovers of the sport of curling have never yet

incorporated themselves into a society, and are still labouring under the

want of many valuable advantages which might be attained thereby.

"The accumulated benefits

which accrue from an united body, and which are enjoyed by each individual

are priviledges which every social spirit longs to be possessed of.

"Partly animated with the

hopes of attaining those invaluable ends, but more especially excited

thereto by the following circumstance (having formerly each of us severally

contributed to the forming and maintaining of a canal for the purpose of

curling, in the Aluir of Hamilton, upon a liberty being granted by the

magistrates of the said place so to do, and having done the same at a

considerable expense. The honorable magistrates in consideration of which

have been pleased again to confirm the same priviledges to us as a society

by honorary promise, investing us with the exclusive power of managing,

supporting, and employing that canal in all respects as we shall find

necessary for enjoying the sport of curling, and by their authority to

maintain these powers granted to us when occasion requires).

"Actuated by these flattering

inducements we do now hereby constitute and form ourselves into a regular

society for the purpose of managing the above mentioned canal, and likewise

ordering ourselves in other respects as becomes a company of curlers."

The "Articles of Regulation"

that follow the manifesto, like others we have noticed, refer chiefly to the

conduct of business. A. Preses and four "managers" are appointed, to whom

are "committed the executive powers of the society to act agreeable to their

resolution, and in every other respect as they may find necessary for the

interest thereof": the entry-money is fixed at one shilling and sixpence

sterling, to be paid "by way of annual supply," to keep up the canal and

meet other expenses. Members are to be admitted by ballot or general

consent, and in all Baines they are to be "preferred in the draught before

strangers." In the list of original members some are marked "dead" and

others "run awa'," a distinction which we may safely presume is not now

necessary. The society was evidently more cosmopolitan than its neighbours,

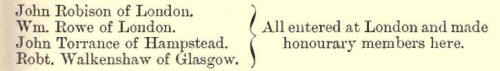

for we have under date 1796, December 27, the following admissions:—

The magistrates and the

curlers of Hamilton seem to have worked very amicably together, and some of

the council must not only have been patrons of the society, but proficients

at the play, for several Dailies in the early times held office as masters.

Magisterial protection does not seem, however, to have extended to the loch,

for we find frequent payments for "publishing with the drum," offering

rewards for information as to Parties who destroyed the ice and the bank of

the loch; while the "watching" of the loch by the officer is an expensive

item in the yearly accounts. This personage, destined in the future to be

one of the "institutions" of every well-regulated society, meets us for the

first time in the following minute:-

"14 Nov. 1781. The curlers

met at John Eglinton's, and," inter alia, "appointed Robert Bruce as their

officer, to warn the meetings and attend on the ice, etc., for which he is

to have a pair of shoes annually at Candelmas."

The cost of the shoes was 5s.

9d., rising gradually to 10s. towards the end of the century, and this

leather salary seems to have been regularly paid. To supply plenty of "cows

for the curlers" was one of the duties included in it, besides those

mentioned above: In 1788 an officer's widow gets 6s. by way of a solatium,

as she was doubtless unable to fill her husband's shoes; and in 1792 another

widow (the office must have had some fatality about it) is paid one guinea.

The officer's inner man was not neglected, as several entries of the

following kind show:-

"To drink to the officer when

cutting the loch, 1s."

In the hour of disgrace the

poor fellow is also allowed a "consideration" in which apparently to drown

his feelings, for we read:-

"HAMILTON, 8th Nov. 1791.

"... The meeting dismissed

their officer, and the managers appoint to meet this (lay fortnight at

Humphrey Crearrer's in order to make choise of a new officer. Every member

that chooses is desired to attend, and dinner to be on the table precisely

at 3 o'clock. The meeting agree that the clerk when dismissing the oj7icer

fire him 2s. 6d. to drink for warning extra meetings."

It

is only indirectly that the Hamilton records furnish any information about

the game as it was then played. Each rink, or rack, as it is called,

consisted of seven, sometimes of eight players, and up till 1836 one stone

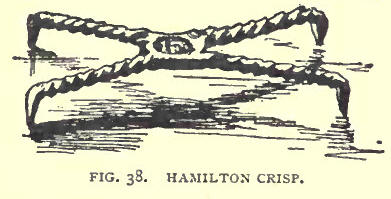

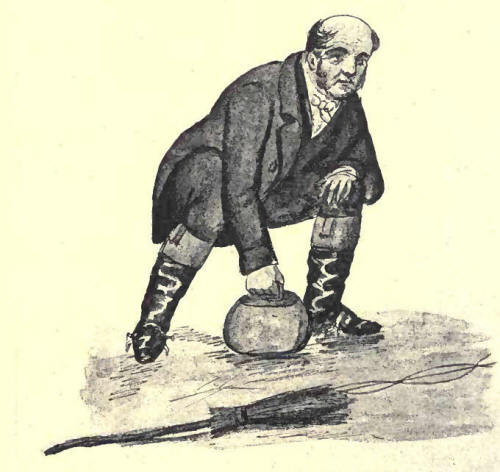

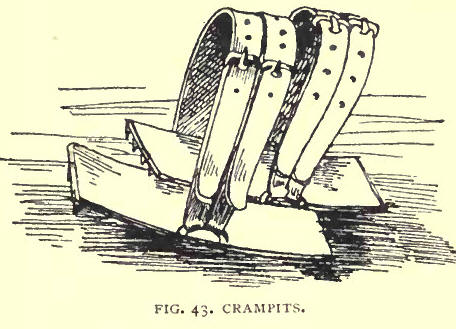

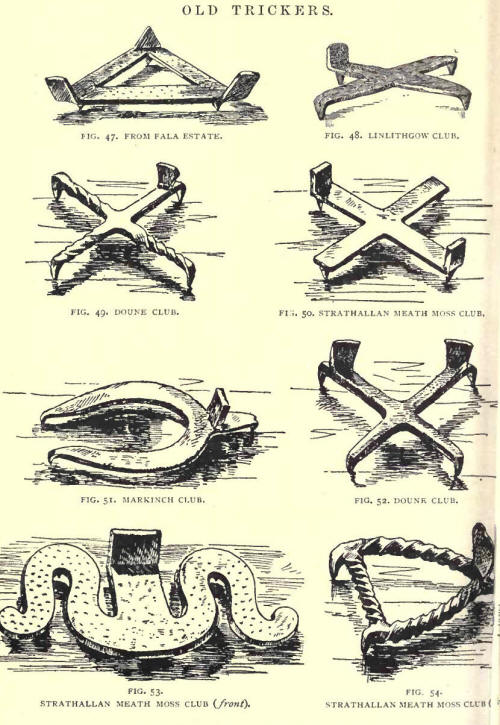

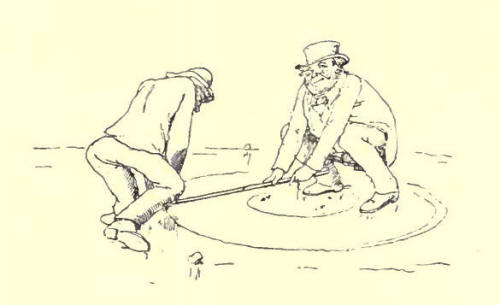

was used by each player. The Hamilton player, in delivering his stone, did

not use the hack; in the ice as he now does, but steadied himself on the

crisp, an iron cross with prongs for fastening it in the ice, of which we

have here a specimen said to be 200 years old. The article was certainly not

costly, as appears from this entry in the accounts:- It

is only indirectly that the Hamilton records furnish any information about

the game as it was then played. Each rink, or rack, as it is called,

consisted of seven, sometimes of eight players, and up till 1836 one stone

was used by each player. The Hamilton player, in delivering his stone, did

not use the hack; in the ice as he now does, but steadied himself on the

crisp, an iron cross with prongs for fastening it in the ice, of which we

have here a specimen said to be 200 years old. The article was certainly not

costly, as appears from this entry in the accounts:-

"1782. April 16. By cash paid

for crisps £0 2 0."

Some years later there occurs

the following reference to some mechanical appliance for describing, the

broughs not unlike that now in use:-

"To Thomas Miller for making

the wood with pricks for marking the toesee and circles on the ice . £0 1

0."

The earliest notice of a

bonspiel occurs in 1792, January 21, when

"Five racks [rinks], four out

of the town and one of the parish, met with five racks from Cambusnethan on

the Dead Waters and played a bonspele, 155 game."

The "box" of this ancient

club was not replenished, as in the clubs we have noticed, by any extensive

system of fines, though fining was at times resorted to, and that even in

the case of members of the High Court.

"12 Nov. 1793. James Mack

never having attended during the whole last year as a manager, it was

unanimously agreed he should be fined. The vote carried 5s."

No rule against profane and

insulting language seems to have been needed. These good old curlers were

evidently true to their original bond of union, and able without the force

of fear to order themselves in all respects "as became a company of

curlers." They had meetings for business and social enjoyment twice a year,

and the different hostelries in the town—"John Klinton's," "The Fox and

Hounds," and about a dozen others—were all patronised in turii, the evenings

being spent, as the records relate, " with the greatest possible

conviviality and hilarity," and "with all the mirth and glee of curlers."

Nor was the sympathy that sweetens the curler's cup of enjoyment unknown to

them, as the following proves:-

"HAMILTON, Jan. 29, 1795.

"This night a quorum of

curlers met in the house of Wm. Clark, and," inter alia, "appointed a

general meeting of the society to-morrow night to take into consideration to

give something to the poor, as a subscription is opened for that purpose in

the town."

New members were formally

initiated by the society at these meetings, and had the "word" and the

''grip " communicated to them, the secrecy and correctness of which they

were held bound to preserve.

John Frost in these days, as in ours, was a fickle friend; he would take

offence and not visit Cadzow for a season, and all the arts of the warlock

Taira Pate, and the prayers of Tam's contemporaries, could not avail to

bring him out of the sulks. This will spew how they acted then:

"HAMILTON, 5th April 1791.

"This night met in the house

of John Eglinton, by desire of the Preses, the following persons, and took

their dinner, as they had no bonspel this season, there being no frost."

Were not these ancients wise?

Why should they lose their dinner because they had lost their play?

BLAIRGOWRIE (1783).—The

earliest records of this old club are found in a small volume which covers

the period 1796-1811. The story of its first thirteen years cannot therefore

be told. In the next minute-book of the club, which has been very carefully

kept by the different secretaries from the time of James Duffus to that of

John Bridie, we find, however, an old document that gives indisputable

evidence of the club's earlier existence. This is a reply to a challenge

which had evidently been sent from Coupar-Angus to Blairgowrie, and is as

follows:-

"To the Reverend Mr

Thomas Hill, , C. Angus.

The curling society of

Blairgowrie present their respectful compliments to Mr Hill, and will do

themselves the pleasure of meeting eight of the Coupar Society on the Loch

Bog in terms of their challenge.

"BLAIRGOWRIE, Thursday

forenoon, ten o'clock, 1784."

A minute-book of the club,

containing records previous to 1783, is said to have been lost; and there is

one amusing tradition which would lead its to believe that the Blairgowrie

curlers played for beef and greens as far back as the Rebellion of 1745.

Both sides on that occasion lost the prize, and the landlord more than

likely lost the reckoning. In an "ode" written by Mr Bridie, and recited at

the centenary celebration of the society in 1883, we have, in the style of

the Address to a Mummy, a history of the Blairgowrie Club, in which a

certain incident of the Rebellion is thus detailed:—

"Tradition tells a story of

the village,

About the `forty-five' or still more early,

Of rude invasion, foraging, and pillage

By some bold soldiers following Prince Charlie

Who on a winter evening came to Blair,

And greedily ate up the curlers' fare.

"Ah, who can faithfully depict

the scenes,

How these marauders rallied in a body,

And made a mess of all the beef and greens,

And swallowed rather than discussed the toddy,

And put the innkeeper in consternation,

Awed by the military occupation

"What could he do? Though in

himself `an host'

He was confronted by an armed band

Of hungry fighting men, each at his post,

Obeying his superior in command

What wonder if he got a little nervous,

So cavalierly pressed into `the service.'

"Then who can realise the

blank despair

Of all the curlers, tired and hungry too?

Winners and losers of the game were there,

Prepared to cline as curlers always do,

And round the festive board to meet, and sink

Their petty quarrels in a friendly drink."

The rules of the Blairgowrie Club were framed in 1796 by the Rev. Mr

Johnstone, minister of the parish—the president, and a committee. An annual

dinner is the first thing to receive attention in the rules, and this seems

to have been of great importance. Members who sent an apology and did not

dine were fined sixpence. Those who neither sent an apology nor came to

dinner were afterwards fined one shilling; and as this did not secure a full

attendance, a fine of two shillings and sixpence was imposed on all

absentees. "The utmost harmony and conviviality,' according to the common

entry in the minutes, prevailed at these gatherings. Tom, Dick, and Harry

were not eligible, for the rule as to membership was this:-

"No person can be admitted a

member of the society unless recommended by one of the members as a person

of good character, who has formerly played on the ice."

But notwithstanding this

protecting clause, it was still thought necessary to enact the following:

"RULES FOR THE REGULATION OF

THE MEMBERS WHILE ON THE ICE AND IN SOCIETY.

"No member, while on the ice

and in society, shall utter an oath of any kind, under the penalty of

twopence teties quoties.

"No brother curler shall give

another abusive or ungentlemanlike language when on the ice and in society,

or use any gestures or utter insinuations tending to promote quarrels:

otherwise he shall be liable to be fined for the same at the discretion of

the members then present."

The utmost conviviality

mentioned above was scarcely consistent with the following rules as to the

quantity of drink to be consumed on special occasions:-

"The members, when playing

among themselves in a birled game, shall not spend more in a publick-house

upon drink than sixpence each for one day. If, however, a regular challenge

is given and accepted by one class of curlers to another, the expense on

such an occasion may amount to but not exceed three shillings each to the

losers, and the gainers half that sum."

Most of the earlier minutes

record sundry fines for failing to observe the rule that each person:-

"Shall be bound within three

months from the date of his admission to provide himself with two

curling-stones, which must be approved of by the society; or in case he fail

to do this within the above period lie forfeits five shillings that the

society may therewith provide stones for him, and lie shall not be at

liberty to carry them away, as they are understood to belong to the

society."

A supply of stones, "not less

than three dozen," was also provided and kept in repair at the expense of

the club. These were got from the Ericht when it was "in ply," and the work

of finding them does not seem to have been very easy, for we read on 15th

July 1799, that a committee at the command of the Preses.

"Proceeded up the water of

Ericht, and they have to report that they found and laid aside a

considerable number of stones out of which eighteen or twenty very excellent

curling-stones may be picked, and the committee request, as they have been

at considerable pains in searching out the stones, that another committee

should be named to bring them home."

The cost of "handling" them

after their home-coming may be reckoned from the following account:—

An inventory of these stones

(of some of which drawings are to be found at p. 41) is now and then entered

in the record, and at one time their number is put down at "fourteen dozen."

They would appear for a long time to have been protected by no covering, but

simply to have been kept together by a chain. In the beginning of this

century, however, a house was erected for theirs at a cost of twelve

shillings and elevenpence, from which cost four shillings fell to be

deducted as "the price of the old chain sold!" [In 1819 a stone and lime

house was built for £7. In 1881 a brick one cost 150. Such is the benefit of

civilisation.]

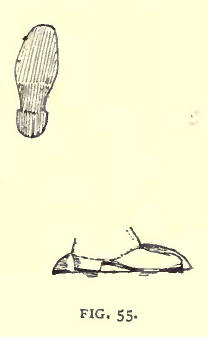

No information is given in

the earlier minutes as to the form of play. But in this, as in other old

clubs, the rink generally consisted of eight, and was presided over by a

director. Grips were used for footing in delivering the stone, and Rule 8

prescribed that

"No member shall be seen on

the ice as a player without a broom, under the penalty of twopence stg."

Members would appear to have

been "initiated," though the traditiont as to "white-headed Jamie Cammell"

and the Coupar-Angus Club having been the means of communicating the sign

and secret to Blairgowrie (Annual, 1842, p. 60), finds no support in the

records. Prompted by that sympathetic spirit to which we have had to refer

in the case of other old clubs, the Blairgowrie curlers in the early part of

this century organised a "charitable fund" for the benefit of members

requiring occasional relief, and for "any other charitable purpose." The

"fund" only continued for a few years, but while it lasted it seems to have

done good service.

MUIRKIRK (1784).—The Rev. Mr

Sheppard, in his Account of Muirkirk, written about the end of last century,

informs us (ride p. 107) that curling was the people's chief amusement in

winter, but he makes no reference to any society of curlers which may then

have existed in the parish. As the minute-book of this society has recently

gone amissing we are unable to do justice to its antiquity, or to give

therefrom extracts illustrative of eighteenth-century manners and customs.

That the Muirkirk people are proud of their old club, and ready to do honour

to its age, is sufficiently proved by an account of the centenary

celebration in the Cumnock Express of date February 16, 1884. At this happy

and enthusiastic gathering, which was presided over by J. G. A. Baird of

Muirkirk and Adainton, the secretary, Alexander Donald, schoolmaster, gave

an interesting account of the history of the society, from which, in the

absence of the records, we may be allowed to quote:-

"The celebration of the

centenary of a society wakens up imagination, and is a particularly

suggestive occasion. In the first decade of the eighteenth century all

Scotland was in agitation over the loss of the Edinburgh Parliament; and as

debate followed debate the fury of the people grew more intense, till at

length the Duke of Hamilton summoned all the Lowlanders to muster to the

fray. Muirkirk made a brave response, and raised a large volunteer corps,

which only awaited the signal to march to Edinburgh. Now, it was the sons of

these patriots who met in 1784 and founded the Muirkirk Curling; Club.

henceforth they believed that `peace bath her victories no less renowned

than war'; they beat their fathers' swords into curling-stone handles, and

studied war no more. lien with such blood in their veins could never sit

through the long dreary winter by the cheerless ingle-cheek in

`The Auld clay biggin'

An' hear the restless rattons squeak

About the riggin'.'

..... These old farmers were

public-spirited, and beguiled the tedium of winter by playing at the kuytiny

stane. A stone was obtained in the channel of the river; a niche was chipped

out for the forefinger and thumb, the stone being partly cuist or cuited

along the ice. Then came large hemispherical blocks, the handle being fixed

at one side.

The earliest historical

document I can get my hands on is of date 1791, when reference is made to a

match between Douglas and Muirkirk, and it is added that nearly thirty years

had elapsed since the two clubs had met, thus carrying the existence of a

curling society back to 1760. . . . . The regular minutes begin in 1783, and

continue up till date."

DOUGLAS (1792).—A neat little

quarto volume, entitled Minute-Book, Douglas St Bride's Curling Club, gives

us a good many interesting notes about the early days of curling, of some of

which we shall defer making use until we come to deal with subsequent

chapters. The organisation of the club, as set forth in the riles adopted by

the ice-players in the parish of Douglas on 25th January 1792, does not

differ much from that of other societies already noticed. The office-hearers

were president, vice-president, six directors, and a treasurer and clerk,

all of which "must execute their respective offices without any salary or

gratuity whatsoever"; and of the two first-named one "must always reside

within a mile of the town." An officer was also appointed "to warn all the

players whenever desired by the president or any of the directors"; his

salary to be five shillings yearly. The entry-money of members (who were

duly initiated on entry by receiving the word and grip) was sixpence, and

the annual subscription threepence. This was a small sum, but it seems to

have been amply sufficient for the society's wants in those days, for the

only expenditure we hear of in the earlier record is at a meeting in the

house of Douglas Sleigh, vintner, on 25th January 1793, when

"Thomas Brown presented his

account for carrying stones to Muirkirk, amounting to six shillings, which,

being examined and approved, orders were given to the treasurer to pay the

same—also five shillings to the officer as his salary. And two shillings and

sixpence to John Brown's daughter at Claydubs, as a small recompense for the

trouble he is at with the curling-stones belonging to the society."

In regard to the arrangement

of players in rinks, Rule 4 thereanent was to this effect:-

"The players shall be divided

by the office-bearers into racks, and places in these racks in all parish

games, and any person refusing to play in the place allotted to him shall be

fined in the sum of sixpence."

The Douglas Society seems to

have kept up a series of matches with certain parishes in the neighbourhood,

such as Muirkirk, Carmichael, Lesmahagow, Lanark, and Crawford-john, the

results of which are faithfully recorded in the minute-book. These seem to

have been looked upon as of the very greatest importance, for it was enacted

in Rule 6 that

"Any person refusing to play

a parish game, when warned by the officer (unless he can give such an excuse

as the majority of his rack shall approve of) shall be fined in the sum of

one shilling."

Previous to such matches

coming off, the racks (eight players each) practised carefully at home among

themselves. It was wisely stipulated that these matches should not cost any

of the players more than two shillings sterling.

The jubilee of the St Bride's

Club was celebrated in 1842 by a dinner presided over by James Paterson,

president.

"On the right of the chair,"

says the minute, was Thomas Haddow, the senior member of the society, being

then in the 80th year of his age, and 63rd as a player: he was a member at

the first constituting of the society in the year 1792, and from

recollection could relate many of the most eventful circumstances that had

occurred in curling duriiia the bygone half century."

In a poem [The Douglas

Bonspiel: A Poem. Though written in 1806 the poem was not published till

1842.] written by Captain Paterson about the beginning of this century are

duly celebrated the deeds of Thomas Haddow (who is said to have been the

prototype of Lazarus Powhead in Scott's Castle Dangerous), and of other

ancient worthies among the curlers "of that loved place called Douglasdale."

Skipper Tam (Haddow) draws the broughs with "knife and string." Another hero

is described as glancing up the rink

"With stone in hand and foot

in natch

In attitude of dire despatch;"

while of Bailie Hamilton it

is said

"A better drawer ne'er clapped

foot in natch;

He once, near Bothwell Brig, with dext'rous cunning,

Drew through a ten inch port for three times running

The rink in length was forty yards and nine,

As measured by Tam Haddow with his line;

And when the stone they in the port did place,

On neither side was there an inch of space;

The ice in length was forty-two yards good,

Down from the pass to where the bailie stood;

The plaudits loud from lookers-on and all,

Alarmed `The Douglas' in his castle hall."

Darkness descends on the

players, and when " the fun " is thus ended,

"Reluctantly they think upon

their homes,

And now in Flecky's barn they lodge their stones;

Then future matches made—wi' muckle sorrow

They all depart, resolved to meet to-morrow."

DUNFERMLINE (1784).—The

minutes of the old curling club of Dunfermline extend from 2nd February 1784

to 2nd February 1808. After the latter date the club seems for a time to

have been inactive till 1821, when a new club was formed, into which the few

surviving members of the old club were admitted. The old minute-book was

then handed over to the united club. From the list of members we infer that

the club existed for some time previous to the date of the first minute in

the volume, for we find Adam Paterson and five others entered as members in

1778, and the first meeting recorded is called the "Anniversary Meeting of

the Curlers." The designation of club is used in 1785, and as far as we can

judge this is the earliest use of the word among the old curling societies.

This club ought in our estimation to be held in honourable remembrance

because it was the earliest to recognise the necessity of having a chaplain

among the office-bearers, and to "William Peebles" belongs the honour of

having been the first spiritual adviser of any curling club. The other

office-bearers were president, vice-president, clerk, and treasurer. It

would appear that these offices were objects of ambition among the members,

for in the first minute we find it declared

"That if any member in the

society shall at, or preceding any future election, either ask or solicit,

or employ for them to ask or solicit, a vote for any office herein [the

member] that shall so solicit or employ any for him so to do, shall not only

be declared incapable of any office, but shall be expelled from the society

for so doing, and this regulation shall be a standing rule in future."

The entry-money of members

was fixed at two shillings and sixpence, of which one shilling only was

applied to the society's use, and one shilling and sixpence was spent by the

meeting as usuall—i.e., we presume in enabling members to drink "a few

toasts suitable to the occasion," as they seem always to have done at their

anniversary gathering. While the office-bearers were not allowed to canvass,

they seem to have been allowed to pay cann (a donation to the funds, which

we hear of in no other society), for we have under date February 2, 1795,

the following appended to the minute:-

"N. B.—Praeses cann 2s. 6d.,

vice do., 1s., secretary, 6d., chaplain, 6d. Treasurer being always contd.

pays no cann."

Penalties were inflicted on

those who did not respect the sociality of the club, and any person who did

not attend the anniversary meeting was fined two shillings and sixpence,

unless he had a valid excuse.

In 1784---

"The meeting unanimously

declared their displeasure at so many new entrants neglecting to attend the

anniversary meeting, lays them under the bane of the society, and shall

admit none of them without a satisfactory excuse, or repeating their entry."

Twenty years later we have

the society dealing smartly with three members who had promised to cline,

but did not appear—they were fined "five shillings each, being their

proportion of the bill." Like their contemporaries, these Dunfermline melt

as they (lined did not forget the needy, for it is stated that after dinner

on February 2, 1785, the meeting

"Distributed five shillings to

the boor and other necessary uses."

We look ill vain in this old

record for any news about the method of play. Each "entered curler" was

bound to have two curling-stones of his own property upon the ice, but we

cannot determine whether at that early date these two stones were—contrary

to the custom of the time—used by their owner in the practice of the name.

There is no mention of directors or rinks, or of any "word" or "grip" in

use, and it is not till the minute of 2nd February 1804, that any notice is

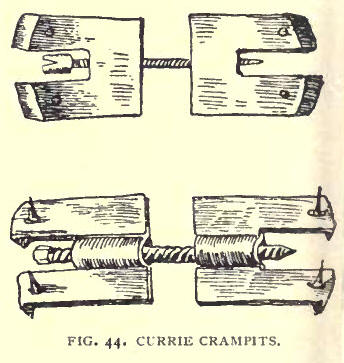

found of the implements of war. Then, after passing an account of six

shillings for crampets and for preserving the stones,

"The meeting authorize the

Preses to get the stair on the south side of the pond taken down and

enlarged, and door and lock put upon it to hold the curling-stones, crampets,

brooms, &c., and that the expense be defrayed by the club."

DUDDINGSTON (1795).—No

records have been preserved of a curling society which is said to have been

instituted at Duddingston about the middle of last century. The later

society, instituted in 1795, and the minutes of which, with a few blanks,

extend onward from that date to 1853, is by far the most important of all

the eighteenth-century curling societies. Dr Cairnie, writing in 1833, says:

In mentioning societies of

curlers, the Duddingston certainly merits to be placed the first on the list

as containing many members who are highly eminent for scientific knowledge,

wealth, respectability, and worth."

In the strict order of time,

Duddingston, however, falls into the last place in this chapter, though we

cordially agree with Cairnie's verdict. This is not unfortunate, as the

transition from ancient to modern curling is distinctly connected with the

formation of the Duddingston Society. The regulations drawn up in 1795

differ but little from those we have already described; the ideas of our

forefathers as to the high character of the game, and its power to promote

health, mental vivacity, loyalty, and religion, are well expressed in the

Resolutions; while the Laws of Curling adopted by the club are the

embodiment of the collective wisdom and experience of the earlier societies.

These Regulations, Resolutions, and Laws, while shedding light on the bygone

century, open up at the same time a new era in curling, and their influence

is manifest in all the societies which were formed between the time of the

Duddingston decrees and the formation of the Grand Club in 1838, when a

greater than Duddingston arose to guide the destinies of the national game.

The Duddingston Club was, in the end of the last and the earlier part of the

present century, a kind of Grand Club. Its name went far beyond its local

habitation, and it numbered among its members distinguished curlers from all

parts of Scotland. Besides, the old Duddingston curlers did more than

exercise themselves on the ice during the day and meet for dinner and drink

at night—they turned attention to the past, and sought to collect all

available information as to the origin and progress of the game, and under

their auspices the first history [Ramsay's Account of the Game of Curling,

1811. The work was read and approved of by a Committee of the Society before

it was put into the publisher's hands, and on being published its sale was

promoted by the members. Songs and all documents in the society's possession

were handed over to Ramsay for use in the volume.] of it was published. Like

their brethren at Canonmills, they also had songs specially written for

their annual meetings, some of which have perhaps done more than all the

rules and regulations to popularise the national game. As the precursor of

the Grand Club, at whose instance we write, we may therefore well award the

place of honour among last century clubs to the Duddingston Society.

The minutes open with this

formal document

"Duddingston, 24th January

1795.

"Curling bath long been a

favourite amusement in many parts of Scotland for many ages past. It is an

exercise very conducive to health, tends to promote society, and often

unites its votaries, who come from north, south, east, and west, in the

strongest bonds of friendship.

"The inhabitants of the small

parish of Duddingston have long been famed for their attachment to the manly

exercise of curling; this was greatly promoted by their having a large loch

conveniently situated and near to the Metropiles. Some years ago a society

was formed to keep up the spirit of this diversion, which seemed to be fast

falling into decay. Of late several gentlemen who have already joined the

society, and others who wish to do so, have expressed a desire that a few

rules might be drawn out and laid before them to be inspected by the

society, and, if approved of by the majority of the members, would be

adopted for regulating the future conduct of the society. A committee of

their number was appointed for the purpose of drawing up the rules--viz.,

Messrs Thomas M'Kill, Michael Linning, David Scott, and John Edgar—which

they accordingly did, and were approvers off by all the members present, and

is here inserted as follows, viz.:--

"RESOLUTIONS AND REGULATIONS

OF THE CURLING CLUB OF DUDDINGSTON.

"'1. Resolved that the sole

object of this institution is the enjoyment of the game of curling, which,

while it adds vigour to the body, contributes to vivacity of mind and the

promotion of the social and generous feelings.'

"'2. Resolved that peace and unanimity, the great ornaments of society,

shall reign among them, and that virtue, without which no accomplishment is

truely valuable and no enjoyment really satisfactory, shall be the aim of

all their actions.'

"'3. Resolved that to be virtuous is to reverence our God, religion, laws,

and king, and they hereby do declare their reverence for and attachment to

the same.'

"The said curling club, in

order to the permanent and regular existence of their institution, have

adopted the following regulations."

The "regulations" which then

follow are, as we have remarked, very like those which have been given from

other clubs. We have our old friend protesting against "strong language" in

No. 4 "He who utters an oath

or imprecation shall be fined in the suns of threepence."

To this is added a new and

salutary prohibition in rule 5

"Any member introducing a

political subject of conversation shall be fined in a penalty of sixpence,

to be paid immediately."

Besides president,

vice-president, and secretary (the last-named receiving remuneration for his

trouble, and having his fees as a member remitted), .Duddingston Club

created quite a number of ornamental and useful offices. They had a chaplain

as at Dunfermline, the first being the Rev. Mr Bennet, minister of

Duddingston, who seems to have been very liberal toward the club in giving a

site on the glebe for a curling- house, and otherwise doing a great deal for

its prosperity. Their "officer" was an important personage, and had, besides

his salary, "a coat with suitable uniform provided for him. When assessments

and fines were imposed, the officer was sent to "the respective lodgings" of

those who had not paid, to collect the same, and he had to see to the safety

both of curlers and skaters; the skating club, which seems to have worked

amicably with the curlers, having provided a ladder and ropes, which, in

case of accidents, were under the officer's care. One of the members was

elected "Master of Stones," and his duty was to see that each member on

entry lodged a pair of stones in the curling-house, which, in the event of

the member's removal, remained the property of the club. There was also a

surgeon to the society (Mr Bairnsfather, Liberton, being the first elected

to that office); a poet-laureate, a medalist, and a body of counsellors

composed of "gentlemen permanently residing in Edinburgh," whose duty it was

to assist the president and judge as to applications for admission to the

club.

Parties who wished for

admission had to apply in writing, and on being approved by the council

their names were submitted to the general meeting. The entry-money was at

first three shillings sterling, and if the entrant did not bring along with

him two curling-stones he had to "pay down five shillings in lieu thereof."

There does not appear to have been any ceremony of initiation, but in 1802 a

motion was carried that a silver medal. "with proper insignia as a badge, to

distinguish the members from any other gentlemen," should be worn, and the

entry-money was thereupon raised to one guinea, which covered the extra

expense of the medal. This badge, under the penalty of one shilling, had to

be worn on the ice and also at the anniversary dinner. Mr M'George having

given the "dye" for the same gratis, "in the most polite planner," was

appointed medalist to the society. Some years after, the price of admission

was raised to three guineas, and as there were frequent extra assessments,

the membership of the society must have been rather an expensive luxury. In

the course of its existence the Duddingston Society seems to have become

very much a legal one, for we find that on one occasion, when no fewer than

seventy new members were admitted, there were in the number twenty-nine

advocates, twenty-two writers to the signet, nine writers, and two

accountants. No society of the kind, notwithstanding this preponderance of

"wig and crown," ever numbered in its ranks such a company of peers,

baronets, judges, and representatives of the different learned professions,

as these names prove:-

"Marquis of Queensberry,

Marquis of Abercorn, Sir Thos. Kirkpatrick of Closeburn, Sir George

Mackenzie of Coull, Sir Alexander Boswell of Auchinleck, Sir Alex. Muir

Mackenzie, Sir George Clerk of Penicuick, Sir Patrick Walker of Coats, Sir

Chas. G. S. Menteath of Closeburn, Sir Wm. Gibson-Craig of Riccarton, Sir

Charles Gordon, Sir Charles Douglas, Sir John Hay, Sir William Hamilton, Sir

John Dick, Sir Alex. Macdonald Lockhart, Sir Patrick Walker, Sir Robert

Burnett, Sir John Gillespie.

"Lords Murray, Cockburn,

Ivory, C Moncreiff, Fullarton, Cunningham, Jeffrey, and Gillies, Colonsay

"Major Iamiltou Duudas of

Duddingston, Colonel Macdonald of Powderhall, Lieut.-Col. White.

"Henry Fergusson of

Craigdarroch, John Clerk Maxwell of Middle-hie, Lauderdale Maitland of

Eccles, Robert Dundas of Arniston, James Maidment, Cosmo Innes.

"Principal Baird, Professor

Dunbar, Professor Ritchie.

"Revs. John Ramsay of

Gladsmuir, John Thomson of Duddingston, Dick of Currie, James Muir of Beith,

John Somerville of Currie, James Macfarlane of Duddingston, G. S. Smith,

Tolbootlh, Wm. Proudfoot, Strathaven.

"Drs Cairney, Berry, Dyniock,

Bairnsfather, Dumbreck, Mackenzie, and Stewart."

"In order to prevent disputes

and ensure harmony argon; the members," it was resolved by the society in

1803 to prepare a Code of Laws by which the play should be regulated. Messrs

Home, David Scott, Millar, Linnin„ M'George, Edgar, Trotter, Ewart, and Muir

were the committee appointed to do this work. In presenting their report