|

"In ancient days fame tells

the fact

That Scotland's heroes were na slack

The heads o' stubborn foes to crack,

An' mak the feckless flee, boys !

Wi' brave hearts beating true and warns,

They aften tried the curling charm,

To cheer the heart an' nerve the arm

The roarin' rink for me, boys!"

Alexander Maclagan.

It boots not whence the curler

hails,

If curler keen an' staunch he be,

Frae Scotland, England, Ireland, Wales,

Or Colonies ayont the sea

A social britherhood are we,

An' after we are deid an' Bane,

We'll live in literature an' lair,

In annals o' the channel-stare."

J. Usher.

"Our fathers in the clays of

yore,

Bravely themselves in battle bore,

And dearly loved the friendly splore.

To give and take be ready still,

To strike a foe still have the will,

Still guard a friend with all your skill."

Rev. G. Murray (Balmaclellan).

O

leave no stone unturned that might illustrate the History of Ancient Curling

has been our endeavour in the foregoing chapter. By a study of the different

types thus brought under notice, the development of the game may be

distinctly traced. The testimony of the rocks is not, however, to be too

much depended on. Curlers who worship antiquity may hesitate before making

Stirling; their Mecca, because of the venerable black Caaba-stone that is

enshrined in the Macfarlane Museum there. The stone itself is old, but the

date (1511) inserted in it seems comparatively new; and this may be the case

with other specimens that put in claims to great antiquity. We must now look

beyond words of doubtful origin that are used in play, and stones of

doubtful age that are preserved in museums, to historians and poets, whose

works may be expected slowly but surely to reflect the customs and

amusements of the people. Such information as these convey cannot but prove

valuable, and we are therefore dealing with the records of the game in the

order of their importance, when we proceed to notice the evidences of its

origin and progress that are found in our literature. Supposing that what we

have stated as to the obscurity of this form of winter amusement before the

invention of the circular-stone is correct, we do not expect to find much

notice taken of it in its earlier staves. In this we are not disappointed,

for O

leave no stone unturned that might illustrate the History of Ancient Curling

has been our endeavour in the foregoing chapter. By a study of the different

types thus brought under notice, the development of the game may be

distinctly traced. The testimony of the rocks is not, however, to be too

much depended on. Curlers who worship antiquity may hesitate before making

Stirling; their Mecca, because of the venerable black Caaba-stone that is

enshrined in the Macfarlane Museum there. The stone itself is old, but the

date (1511) inserted in it seems comparatively new; and this may be the case

with other specimens that put in claims to great antiquity. We must now look

beyond words of doubtful origin that are used in play, and stones of

doubtful age that are preserved in museums, to historians and poets, whose

works may be expected slowly but surely to reflect the customs and

amusements of the people. Such information as these convey cannot but prove

valuable, and we are therefore dealing with the records of the game in the

order of their importance, when we proceed to notice the evidences of its

origin and progress that are found in our literature. Supposing that what we

have stated as to the obscurity of this form of winter amusement before the

invention of the circular-stone is correct, we do not expect to find much

notice taken of it in its earlier staves. In this we are not disappointed,

for

No mention is made of

the game of curling by any of our Scottish historians and poets previous

to the year 1600,

So far our present chapter must prove a case of

"snakes in Iceland." Its negative nature cannot be satisfactory to curlers,

who believe that their favourite amusement was one at which our

monarchs—when we had them all to ourselves—"disdained not to play," and that

curling was a national game perhaps before we in Scotland were a nation. We

are sorry, for their sakes, that we cannot go further back; but as for

curling, we see nothing to be gained by pushing its claim to antiquity,

nationality, and Royal patronage too far. The popularity of the game rests

on its merits. It has the future before it, as the winter game of this and

other countries; and in our present inquiry it is better to clear the

ground, though it may not please our antiquarian brethren to find their pet

traditions destroyed. We have already stated that curling of a kind was

engaged in, during the sixteenth century, when the kuting-stone, or

piltycock, was in use. No illusion is however made to it, in the history or

poetry of that period; and before the sixteenth century we have no evidence

either from ancient stones, or from ancient writers, that such a game or the

germ of it was in existence. This the keen historian does not wish to

believe. He is determined to force the testimony, and so we, find him "owre

a' ice," in his wild pursuit of references. Here is a passage from Sir

Richard Broun, one of the best and most enthusiastic of early writers on

curling:—

"Of the remote antiquity of the game of curling,

we have the most legitimate proof from Ossian:- 'Fly, son of Morven, fly!

Amid the circle of stones, Swaran bends at the stone of might.' Either the

game then is much more ancient than has hitherto been dreamed of—or else

Macpherson has been most unhappy in his allusion!"

We have looked in vain for this interesting

passage as quoted by Broun, but "the stone of might" is a common expression

in Ossian's Poems. The words of Starno and Swaran (Ca-lodin, Duan I.) are

"not in vain, by Loda's stone of power." In Fingal (Duan III.) we read of

the "gray-haired Snivan that often sang round the circle of Loda; when the

stone of power heard his voice, and battle turned in the field of the

valiant." These references, it appears, are to acts of worship performed by

the Fingalian heroes.[Clerk's Ossian, Vol. I. p. 78; Vol. II. p. 136.

Blackwood, 1870. Clerk's translation has "stone of spectres" for

Macpherson's "stone of power."] Broun need not have been at the trouble of

transforming Scandinavian crom-lecs into Caledonian channel-stanes. Is it

not plain that Swaran was a curler-"Swaran of lakes," who, "slowly stalking

over the stream, whistled as he went"? Was it not a signal for a curling

match to begin when "Launderg rolled a stone the sign of war"? Why did the

son of Maben not penetrate further into ancient literature, and find in the

Fall a proof that our first parents tried the "slippery game" in the garden

of Eden? [Broun should have been credited with a joke, had we not found from

a MS note to a proposed second edition of his work, that he prepared to

enlarge on the point, and to add some remarks on the popularity of the poems

of Ossian with Napoleon Bonaparte and Lord Byron. Since his time, "the stone

of might," and "the circles of Loda," are often found doing duty in curling

songs. The Rev. Mr Muir of Beith, in the following spirited lines, gives a

happy account of another transformation of "the stone of might." The lines

were published in Broun's work with the motto from Ossian prefixed.

"In the days o' lang syne, as some auld stories

tell us,

At Yule when the feel's are a' kiver'd wi' snaw;

Nae bonspiel was ken'd but the horn brightly sparkling,

And wild bursts o' joy sounding loud thro' the ha'.

But the watch-fire blazed red on the high top o'

Gaitfel,

The signal weel kenn'd to prepare for dread fight,

For Norseman had sworn, 'mid the circles of Loda,

He would force us to bend at the stone of his might.

"But wi' braid sword and targues we met them at

Largo,

And our laddies bare ad the big stane o' his might!

"To the ice of Loch Tankard our buirdly braw

callans

First bare the big whin-stave, and marked out the tee,

Syne drew the dread hog-score, the hack and the circle

Around which our fathers oft sported wi' glee.

"And ilk year sin sync in the dark dreary

winter,

When the such blasts o' lioreas begin first to bite,

Wi' loud roaring noise round the circles of Loda

We bend, but in sport at the stone of his might.

"While our stones loudly rattle we are ready for

battle,

If the foe dare to try the dread force of our might."

The words in italics are repeated as the song is

sung to the air of Spanking Jack. Gaitfel is the highest mountain in the

Isle of Arran. Loch Tankard is the ancient naive of Kilbirnie

Loch.—Memorabilia, 84-85.]

All supposed references to curling, previous to

the seventeenth century, may be treated like this mythical allusion from

Ossiann—they are unworthy of serious attention. Hail the game been of any

great importance in the century previous, then it is more than likely that

we should have heard of it, as we hear of archery, If football, and other

games.

Archery is the oldest of our national

amusements. In early times it could scarcely, however, be regarded as a

sport, for it was practised by the people, at the command of Parliament, as

the chief method of defence against our enemies before gunpowder came into

use. Football is next in antiquity, being prohibited in favour of the

practice of archery before we hear of golf. [James I. Pan. 1. cap. 17, A.D.

1424.] Then, along therewith, the game of golf is "cryed downe" as

interfering with archery—both Vein; denounced as "unproffitable sportes."

[" It is decreeted and ordained that the

Waapon-schawinges be halden be the Lordes and Baronnes, Spiritual and

Temporal, four times in the yeir. And that the Fute-ball and Golfe be

utterly cryed downe, and not to be used. And that the bow-markes be maid at

ilk Parish Kirk a pair of Buttes and schutting be used. . . . . And that all

men that is within fiftie, and past twelve yeires, sall use

schutting."—James II. Parl. 14. cap. 64 (1457).

"It is thought expedient . . . . that the Fute-ball

and Golfe be abused in time cumming."—James M. Par!. 6. cap. 44 (1471).

"It is statute and ordained that in na place of

the Realme there be used Fute-ball, Golfe, or uther sik unprofitable sportes."—James

IV. Pan. 3. c. 32 (1491).]

Curling is not so ancient as these; and, if it

did exist as an amusement in the fifteenth century, it never came under the

ban of Parliament. Curlers need not be sorry to find that their game is

later in the field. Archery was a game of war; its practice on the part of

the people, by Act of Parliament, did not make it popular, and now it has

almost died out. Football has not escaped connection with bloodshed and

crime. Golf and football [The game of football was much indulged in by the

Border youth, but, unfortunately, at the assemblies held for such purpose,

many of their most daring exploits were planned, and crimes which might

otherwise never have been perpetrated, owe their origin to the meetings of

the hot-blooded Borderers for this apparently innocent amusement. The murder

of Sir John Carmichael of that Ilk, Warden of the West Marches, by the

Armstrongs, was agreed to at a football match at which they were present, on

Sunday, June 15, 1600.—Armstrong's History of Liddesdale, Eskdale, etc.,

Vol. I. p. 83; Douglas, Edin., 1883. Pitcairn's Criminal Trials, Vol. II. p.

364.] were both, in their days of ancient popularity, "cryed downe" by the

Lordis, spiritual and temporal, and prohibited as interfering with the duty

of the people to practise the art of national self-defence. But curling,

"the child of day, of honour, and of sociality," has no antecedents like

these to be ashamed of, and we ought to be proud that it has come down to us

with no stain upon its character. The little loss of antiquity which some

are so eager to deny, is really a gain of dignity, for which curlers ought

to feel thankful. We are better without "historical references " when these

are blots upon our good name.

The traditions as to the royal patronage of

ancient curling require a little attention. It is generally supposed that

several of the Stuart kings were "keen curlers." The wish, we fear, has been

father to the thought. For the sake of those monarchs, as much as for the

glory of the game, we would gladly believe that they knew the virtue of the

channel-stane, but our investigations scarcely permit us to do so.

James I. (1394-1431)—in whose time, it is said

by some, the game of curling was introduced from Flanders—was not only an

accomplished poet and musician, but he also excelled in all manly

exercises—such as archery, wrestling, throwing the stone and the hammer,

walking, running, and horsemanship, and "in all honest sports and solace

that could enliven the spirits of his followers." [Bower Scotichronicon. Bk.

xvi. ch. 28, 30.] We have no account of his prowess on the ice. "Feasting,

Baines, tournaments, and every species of feudal revelry," marked the great

occasions of his reign, and the Christmas festivities that were closed in

gloom by the dark and cruel steed which deprived Scotland of one of the best

of rulers "were unusually splendid." [Tytler's Scottish Worthies, III. 44.]

Not a word, however, is heard of curling among all the "gamyn and gle."

As far as we are aware, no suggestion has been

made that James II. or James III. knew anything of the game. Tradition is,

however, determined to have it that James IV. (1472 - 1513) was a curler,

and, no doubt, if the game had been in any degree popular in his reign,

James would have been found enjoying it, in its season, as he enjoyed other

popular games. That the King curled, and that he left a silver curling-stone

to be played for annually by the parishes in the Carse of Gowrie as a token

of his appreciation of the game, are common traditions. We can find no

evidence to warrant belief in their truth. Curling was cheap, and even His

Majesty may have been able to play a game free of expense when the principal

implements were of nature's own making; but a silver stone as a trophy for

the Carse of Gowrie curlers could not have got through the meshes of the

Lord High Treasurer's net, and we find no mention of it, or of any curling

outlay, alongside the items of the King's expenditure on golf, archery, and

the like. [Archery and shooting at the butts, shooting with the crossbow,

and culveryng, playing at the golf and football, not only occur continually,

but in all of them the King himself appears to have been no mean

proficient.—Tytlers Scottish Worthies, III. 3.12.] Brown, in referring to

this tradition (Memorabilia, p. 62), speaks of the Gowrie trophy as if it

were then (1830) in existence. If so, it must since have disappeared. In its

absence we may be pardoned for calling it a myth and without it we have no

evidence to prove that James IV. curled anywhere else than in the

imagination of Sir Richard Brown, or some early writer on the game.

In a second edition of the Memorabilia, this

writer had in view a supposed allusion to curling in the time of James V.

(1511-1542) in Pitscottie's Chronicles of Scotland. The chronicler,

referring to some sports which were held at St Andrews in 1530, when the

King received an embassy from his uncle, Henry VIII., says (II. 347-8):

"In this yeir cam an Inglisch ambassadour out of

Ingland, callit lord Williame, ane bischope, and tither gentlmen to the

numller of thrie scoir horss, quhilkis war all able, wailled gentlmen, for

all kynd of pastime, as schotting, louping, wrastling, rolling, and casting

of the stone. But they war weill assayed in all these or they went home and

that be tiiair awin provocatioun, and almost evir tint, quhill at the last

the kingis mother favoured the Inglismen, becaus shoe was the king of

Inglandis sister: and thairfoir shoe tuik ane waigeour of archerie vpoun the

Inglischmanis handis, contrair the king hir cone, and any half duzoun

Scottismeu, aither noblmen, (entlmen, oryeanianes; that so many Inglisch men

sould schott againes thame at riveris, buttis, or prick honnett. The king,

heiring of this boncpeill of his mother, was weill content. So thair was

laid an hundreth crounes, and ane tuu of wyne pandit on everie syd."

Broun's argument from the above passage is:-

"If bonspiel was a word applied to curling in

the sixteenth century, as in the nineteenth, it carries the antiquity of the

game 130 years further back than the notice of it by Gibson in his edition

of Camdens Brittannoia." [Broun had by this time (1532) evidently

found that his statement on p. 10 of his book—`'The earliest notice of

curling is by Calnbder" in his Brittannia (published 1607) —was incorrect.

To this mistake reference is made in a later note, p. 90. ]

The word was not, however, applied to curling,

as a reference to Jamieson's Dictionary, where the passage is given, might

have shewn. It was applied to a match of archery, and the use of it in this

connection may be handed over for consideration by those who think that the

word bonspiel, now almost invariably applied to great curling matches, helps

to prove the foreign origin of our national game. If that is all that can be

advanced to prove that the "King of the Commons " was a curler, then he also

must be given up. Besides, had curling been played by the Court in the time

of James V., or in that of his father James IV., we should most undoubtedly

have found some reference to it in the poems of Sir David Lindsay

(1490-1555), one of whose duties was to arrange and superintend the Royal

sports. But the good old poet says nothing about it; and it does not appear

that he had found the secret, known only to curlers, of warding off the

severities of winter, and making the season of frost the most delightful in

the whole circle of the year, for it is thus he complains pathetically in

his Prologue to the Dreme (1528) [Laing's Edition of Lindsay. 2 vols., 1871.

I. 7.] :—

Quhar art thow May, with June thy syster schene

Weill bordonrit with dasyis of delyte

And gentyll Julie, with thy mantyll grene,

Enamilit with rosis red and quhvte?

Now auld and cauld Januar, in dispyte,

Reiffis from us all pastyme and plesour:

Allace! quhat gentyll hart may this indure?"

What curler would give "auld Januar," were it

only "cauld" enough, for all the other months of the year?

Of James VI. (1567-1625) golfers may well be

proud. He is their own peculiar patron, and some of their clubs are named

after him. He appointed a club-maker [William Mayne, 1603.] for himself, and

a ball-maker [James Melville 1618.] for the nation, and did much for the

"Royal and ancient game." He also has been credited with a knowledge of

curling. In the year 1844, when a large company met to do honour to the

worthy representative of one of the best old Jacobite families—Sir Patrick

Murray Thriepland of Fingask—the president of the meeting (C. Robertson), in

proposing the health of the Prince of Wailes—then a boy little over two

years of age—thus forcibly commended to His Royal Highness's tutors the

example of James VI.:

"He [the Prince] has scarcely begun his

education, but you will all agree with me in maintaining that if, in the

progress of that education, he is not made a 'keen, keen curler'—if he is

not thoroughly initiated into all the mysteries of that health-restoring,

strength-renovating, nerve-bracing, blue-devil-expelling, incomparable name

of curling—his education will be entirely bungled and neglected. I think

that the Royal Grand Club should take that subject into its earliest and

most serious consideration. We would all deprecate Royal degeneracy. His

ancestors were distinguished for the countenance they gave to the manly and

ennobling exercises and pastimes peculiar to Scotland. It is true that some

of them—such as James III., James IV., and James V. for some time

discountenanced some of the amusements, for the purpose of encouraging the

practice of archery when the country was at war; but James VI. rose in all

the glory of curling, as well as golfing, grandeur, and greatness; he was

not only a distinguished golfer, but a `keen, keen curIer.' He knew how to

keep his own side of the rink, to sweep the rink, his neighbour's stone from

the score to the tee, his adversary's past it. Let the young Prince go and

do Iikewise."

Most excellent advice! Every curler hopes that

the time may come when the education of our princes shall include their

initiation into the mysteries of curling, and when no monarch who cannot "gie

the curler's grip" shall be allowed to ascend the throne. Scotland ought to

insist on this, in these days when national wrongs are all being righted. It

would be well, however, not to rest our demand on the example of James VI.,

put forward with true Jacobite feeling at the Feast of Fingask. There may be

poetry in the statement, but there are no historical facts to support it.

"Henry DarnIe," says Broun, [Memorabilia, p.

62.] "during the severe winter he was forced to spend at Peebles, was much

employed in curling, chiefly on a meadow--now, we understand, part of the

glebe."

This is the last tradition of the Royal

patronage of ancient curling (if we may include the silly young lord in our

list, because of his unfortunate marriage). There is such a circumstantial

air about it that there may perhaps be more in it than in some of the other

traditions. By those who had no good to report of Queen Mary, it was said

that, a few days after Darnley's murder, she "was seen playing Golf and

Pallmall in the fields beside Seton." [Inventories of Mary Queen of Scots.

Pref. p. 70. 1863.] That her husband had been a curler, and—like many

curling husbands—neglectful of his spouse during the frost, may have been

the fair widow's excuse for such conduct. Let all curlers be warned! But

Darnley's curling is perhaps more mythical than Queen Mary's golf; and we

have no proof to shew that Peebles was at the play as far back as 1565,

though the roaring game has been known and practised in that ancient town

for a long time.

Curlers are, of all men, most loyal. The first

and last lesson on the rink is obedience to the "ruling monarch," and such

training makes them obedient to the powers that be. They are proud of the

Royal patronage now extended to the game; but it will be as well for them to

abandon those doubtful traditions as to the kingly countenance given to

curling by the Stuarts. Curling owes nothing, as far as we can see, to any

Royal support given to it in its infancy. That many of the gentry were keen

curlers in the early days of the game is abundantly evident from our present

chapter. In curling they were, however, following their cottars rather than

their kings, for curling at the first was the game of the poor: it cost

little or nothing. Golf, on the other hand, was expensive; it was the game

of the rich. [James VI., in giving James MelviIIe the monopoly of

ball-making, stipulated "that the said patentaris exceed not the pryce of

four schillingis money of this realm." It is remarkable to find that so

expensive a game was so popular, even among the poorer classes, in ancient

times.] Let us only hope that while golf has been so cheapened by the use of

guttapercha, that it is spreading far and wide, curling is not, by expensive

ponds and exclusive clubs, getting beyond the reach of the poorer classes.

If this shall ever be the case then the glory shall have departed from the

game, for it shall have lost the grand power it now possesses of uniting in

the closest brotherhood the different classes of the community.

Between the years 1600

and 1700, we have here and there references to curling-stones, and to

persons who were curlers, but no account of the game.

When we do come to find from historical and

poetical allusions, that curling existed in the seventeenth century, we have

to be content with small mercies. The references are like angels' visits,

"short and far between." Dissertations, songs, and even sermons, on the

subject are in these days "as plentiful as blackberries," and their authors,

however sanguine, do not expect more than a passing notice for their

productions; but those precious little blinks that show us—though but

dimly—our forefathers on the curling-rink must not be so lightly esteemed.

They are valuable because they are so ancient and so rare. So far as we can

judge, the earliest reference to curling is to be found in a "quaint and

curious" work, which was written in 1620, and published eighteen years

later, entitled The Muses Threnodie, or, mirthfull Mournings, on the

death of Master Gall. containing varietie of pleasant poeticall

descriptions, morall instructions, historical narrations, and divine

observations, with. the most remarcable antiquities of Scotland, especially

at Perth. By George Adamson. Printed at .Edinburgh in King James

College, by George Anderson, 1638.

[An edition of this work, with valuable notes by

James Cant, was published at Perth in 1774. The main portion of the poem is

also to be found in Perth: its Annals and its Archives, by David Peacock.

Richardson, Perth, 1849.

The celebrated Drummond of Hawthornden was an

intimate friend of Henry Adamson's, and in 1636 he urged the publication of

the poem in a letter to the author, in which he says:—"These papers

....appear unto me as Alcibiadis Sileni, which ridiculously look with the

faces of Sphinges, Chimeras, Centaurs, on their outsides: but inwardlie

containe rare artifice, and rich jewels of all sorts for the delight and

weal of man."]

This poem is an old Scottish in Memoriam,

differing in more ways than in the exuberant verbosity of its title from

that of Tennyson. in our laureate's long lament over the loss of his friend

Arthur Henry Hallam, we have a poetical account of modern ideas in religion

and philosophy. In Henry Adamson's Threnodie over the death of his friend

James Gall, we have a history of Perth more practical than poetical. The

earlier is to the later work "as moonlight unto sunlight, and as water unto

wine," but the similarity of their mode of sorrowing associates the two in

one's mind.

When Henry Adamson dedicated his Recreations to

his native town of Perth and its civic rulers in the year 1637, he styles

himself "Student in Divine, and Humane Learning." This, at the age of 56,

was a modest estimate of his position,. though it should never be too late

for any one to use the designation. Modesty, however, does not altogether

explain its use by the poet. He was destined for the ministry, and was a

good classical scholar as his work spews, but he got no further than the

office of Reader in the kirk of Perth. From this office he seems to have

been suspended for a. time, owing to an unfortunate love-affair. By his

future conduct he was able, however, to redeem his reputation, and when lie

died in l 637—a —a year before his poem was published—his loss was deeply

lamented by his friends, who all "held him in high esteem for his wit,

learning, and amenity of manners and disposition." George Ruthven

(1546-1638), physician and surgeon in Perth (a relative of the Earl of

Gowrie, who was murdered there in 1600 for alleged treason), was one of

Adamson's dearest friends. He seems to have been a. prototype of Captain

Grose, with "a fouth o' auld nick-rackets," which he called his Gabions,

some useful, some ornamental, and all inseparable from his personality.

James Gall (1595(?)-1620), the friend of both, was a merchant in the town,

well-connected—like Adamson —an accomplished scholar, and a pleasant

companion. He shared the fate of those who are beloved by the rods, and died

of consumption at an early age, though his dear old friend the physician

tried all he could to save him, by the special skill of Apollonian arts,

collecting herbs on Kinnoull and Moredun hills, and administering them to

his patient without any good result. It was a "doleful day" to Adamson and

Ruthven when they lost James Gall. The uses Tirenodie is their united

lamentation over his death, but Ruthven is made to appear as chief mourner,

and, of course, his Gabion must share his grief.

"Of Master George Ruthven the teares and

mourning,

Amids the giddie course of Fortunes turnings,

Upon his dear friends death, Master James Gall,

Where his rare ornaments bear a part, and wretched Gabions all."

This is the superscription of the chief poem

which, as we have noticed, develops into a rhyming account of Perth —the

story being interrupted now and then by the old doctor's wail:

"Gall, sweetest Gall, what ailed thee to die?"

As the gabions are so important, our poet,

however, before entering on the larger theme, devotes a brief introductory

poem to a description of there. It is "The Inventarie of the Gabions, in M.

George, his Cabinet, [Adamson's work is generally called Gall's Gabions, but

this is a misnomer for Rut/ercn's Cabions. " The curiosities of all kinds

with which Ruthven's closet was stocked lie called his gabions, a quaint

word peculiar to himself."—Cant.] and as we read the

There were brave men before Agamemnon, and no

doubt there were heroes on the "watrie plaines" before George Ruthven, but

to him let curlers doff their Tangy o' Shanters as the first of the

brotherhood, until some older hero shall dispute his claim to the honour.

Perth has much to be proud of in the part she has played in the history of

our country. It is not the least of her distinctions that three hundred

years ago George Ruthven taught her citizens, both by precept and example,

what neither the sons of Æsculapius nor their patients yet fully understand,

how much curling and such healthy recreations can do to make men cheerful

workers and "jolly good fellows;" and how the "grassy links" and the "frosen

watrie plaines" must be visited by us with our gabions if we are to do any

good in the world and attain to a venerable old age. [In case the Fair City

should ever think of making itself fairer by a statue in Ailsa of Ruthven,

it may be of advantage to state that "M. George was a bonnie little man."—

V. Threnodie, P. 26.]

The names of two divines follow that of the

Perth doctor in the early references to curling. This will not surprise

curlers, who are aware of the weakness of the "cloth." "Frae AIaidenkirk to

John o' Groat's," says an old proverb, "nae curlers like the clergy." Their

keenaness seems to be a matter of apostolical succession, and that of a kind

which does not cause strife, but which unites them in brotherhood. It seems

to have done this from the very first, for at the head of the long line of

clerical curlers we find an Episcopalian bishop and a. Covenanting minister

"The lawn-robed Prelate and plain Presbyter

Erewhile that stood apart."

shaking hands on the ice, which bridges over the

great religious gulf that lies between them. Henry Adamson's volume, with

its reference to Ruthven and his curling friends, was published in 1638.

This was a memorable year in the see-saw conflict between Prelacy and

Presbytery which so long kept the country in misery. The Presbyterians, in

the famous Assembly which then met at Glasgow, under the guidance of

Alexander Henderson, set the King, Charles I., and the Marquis of Hamilton,

His Majesty's (2ommissioner, at defiance, and determined to make a clean

sweep of the bishops. Instead, however, of sweeping them away because they

were bishops, the Assembly put them to mock trial upon charges that in most

cases affected their moral character. The proceedings were all faithfully

recorded at the time by Pobert Baillie (1599-1662), minister of Kilwin ring,

a member of the House. In his Letters

[Letters and Journals containing an Impartial

Account of Public Transactions, Civil, Ecclesiastical, and Military, in

England and Scotland, from the beginning of the Civil Wars in. 1637 to the

year 1663. These were first published in 1775. Laing's edition, from which

we quote (Vol. 1. pp. 103-164) was published in 3 vols., 1841-42. Buckle

(Miscellaneous and Posthumous Work,, II. '241) calls Baillie the most

learned and one of the most moderate of the Presbyterian clergy," and this

seems a just account. In 1661 Baillie was elected Principal of Glasgow

University.]

we read, under date 11th December 1638 "Orkney's

process came first before us: he was a curler on the ice on the Sabbath day:

a setter of tack, to his sones and grandsones for the prejudice of the

Church: he oversaw adulterie, slighted charming, neglected preaching and

doing of any good there; held portions of ministers' stipends for building

his cathedrall."

Not a good account this of a bishop or of any

other roan, but it must be taken with a grain of salt. George Grahame, [t

George Grahaine, AM., translated from See of 1)unblane to Orkney 1613.

Member of Court of High Commission, 1615, 1619, 1634. He voted in Parliament

4th August 1621, for confirming the five articles of Perth was deposed by

the General Assembly 11th December 1638, and disclaimed Episcopal government

11th February following, prudently preserving his estate of Gorthie and

other property. Died between 1644 and 1647. . . . From the bishop are

descended the families of Blair-Drummond, Methven, and Watt of Skaill.—Dr

Hew Scott's Fasti Eccles. Scot., 1870. V. 458.] for such was "Orkney's"

other name, does not give a very good impression of himself in his

Vicar-of-Bray-like willingness to renounce his Episcopacy that he might

retain his property. But he was not so bad as his neighbours, for the

charges against him were light compared with many that were preferred

against other prelates in that Assembly. It sounds strange to hear of a

bishop curling on the ice on the Sabbath day, but even if the charge had

been true, it did not follow that "Orkney had a double dose of original

silo. The rigid observance of the clay of rest, which has been such a strong

feature of Scotland since that time (though happily modified of late), was

only beginning then to show its horns. It was an importation of English

Puritanism, and not known to Knox and the early reformers. The day was more

of a festival than a fast, and after attending church people were free to

amuse themselves. The bishops shared this freedom, ["They had not that

respect for the sanctity of the Sabbath which has always been characteristic

of Presbyterian Scotland. They aped the greater laxity of Episcopal England.

They saw no evil in a ride on horseback, or a hand at whist, on the Sabbath

; the Bishop of Orkney indulged in curling, and the minister of Glassford

encouraged his parishioners to dance and play at the football when the

sermon was done."—Cunningham's Church History (1854), Vol. H. chap. iii. p.

104.] and Grahame on some stray visit to his former See of Dunblane, where

the game had even then been long; known, as the old stone of "1551"

testifies, may have had a fling with some of his friends on a Sabbath

afternoon, without losing their respect or his own peace of conscience. To

the " soft impeachment " brought against him we should suppose a good many

members of that stern Assembly might have pled guilty. Most likely " the

lads frae Kilwinnin wad send the stanes spinnin " even in those times, for

curling reputations are not made in a day, and if Robert Baillie was the

good minister we take him to have been, lie would himself be a curler, and

charitably disposed to this curling prelate. We shall suppose, for the sake

both of the Assembly and of the bishops, that the charge was departed from

as not heinous, rather than from want of proof. At any rate it came to

nothing.

William Guthrie of Pitforthy (1620-1665) is one

of the most honoured in the list of our Scottish worthies. Covenanting

ministers are generally supposed to have been grim, sour, narrow, and

totally opposed to worldly recreations and amusements. The description does

not apply to Guthrie. He was a devoted pastor, giving up his paternal estate

to a younger brother, that lie might more freely devote himself to his work.

He was a successful and able preacher, whom people flocked from great

distances to hear, and so beloved by the people of Fenwick, of which parish

he was the first minister, that "They turned the corn-field of his glebe to

a little town : every one. building a house for his family upon it that they

might live under the drop of his ministry."

(Would that aII glebes were so populated in

these degenerate glebe-feuing times) But Guthrie was also fond of all manly

exercises and amusements, and these he made subservient to the nobler ends

of his ministry.

"He made them," says his biographer, [Dunlop, in

Memoir prefixed to Guthrie's work, The Christian's Great Interest. Glasgow,

17735, p. xii.] "the occasions of familiarizing his people to him, and

introducing himself to their affections and, in the disguise of a sportsman

he gained some to a religious life, whom he could have little influence upon

in a minister's gown; of which there happened several memorable examples.'

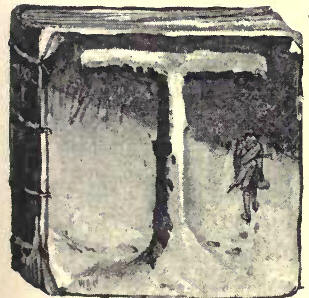

That Guthrie included curling among his athletic

accomplishments is well attested by the veritable kutingstone which he used,

and which is still preserved at Craufurdland Castle. This curious

potato-like specimen we have sketched at p. 36, and it will always be looked

upon as one of the most interesting relics of ancient curling. Later on in

the Memoir from which we have quoted it is said (p. xxv.) He used the

innocent recreations and exercises which them pre-railed, fishing, fowling,

and playing upon the ice, which at the same time contributed to preserve a

vigorous health, and while in frequent conversation with the best of the

neighbouring gentry, as these occasions gave him access, to bear in upon

them reproofs and instructions with an inoffensive familiarity."

The popularity of this old curling Covenanter,

not only with the poor, but with the rich, is shown by the fact that he was

allowed to remain in Fenwick, at the urgent entreaty of "some of the

greatest in the kingdom," long; after his brethren had been driven from

their parishes, but he had at last to turn out by the relentless order of

the Archbishop of Glasgow. His people would have fought for him, but like a

Christian and a curler, he counselled peace and submission to fate; and when

the soldiers came upon the scene, he "called for a glass of ale, and craving

a blessing himself, drank to the commander." Within a year after he died.

Let his memory live for ever among us, for a worthier than he never lifted

the channel-stane; and from William Guthrie may many in this and coming

generations learn how to sweeten their religion by the innocent recreation

"of" playing upon the ice."

The next brief reference to curling in the

seventeenth century gives us a glimpse of some lairds enjoying the Brame

together in the Border district in the year 1684. It is found in

Fountainhall's Decisions, [The Decisions of the Lords of Council and

Session, from June 6, 1678, to July 30, 1712, collected by the honourable

Sir John Lauder of Fountainrhall, one of the Senators of the College of

Justice, Edinburgh, 1759; Vol. I. p. 328. Lauder was counsel for the Earl of

Argyll at his trial in 1681, and a zealous supporter of the Protestant

religion. He was appointed Lord of Session (Lord Fountainhall) after the

Revolution. ] under (late December 30, 1684:-

"A party of the forces having been sent out to

apprehend Sir William Scot of Harden, younger, because Tarras and

Philiphaugh deponed that they communicated remotely their design to hire, as

a roan of good fortune: and one William Scott in Langhope, getting notice of

their coming, by the cadgers or others, he went and acquainted Harden with

it, as he was playing at the Curling with Riddel of Haining, and others; who

instantly pretending there were some friends at his house, left them and

fled. Haiuin; having related this, the said William Scot, and James Scot of

Thirlstone, old Harden's brother, are brought in this day to Edinburgh.

Thirlstone is liberate, as finding nothing to say to him, but William is put

in the irons, because he declined to tell who gave him advertisement of the

party's coming."

Curling lairds had thus their share of troubles

in these weary times as well as the curling clergy. Scot of Harden would

relish his Hogmanay "in the irons" as little as Grahame and Guthrie did

their deposition. Unlike his successor Beardie (the great-great-grandfather

of Sir Walter Scott), who is said to have taken a vow never to shave his

beard till the exiled family of Stuart was restored, and who lost his all in

the Jacobite cause, Sir William Scot, the curler of the seventeenth century,

seems to have been a supporter of the Earl of Argyll in his rebellion

against Charles II. Sir John Riddell of Raining was also disaffected, but

both appear to have got remission after James VI. ascended the throne. Very

soon after this and we come to the hog-line of Scottish history—the

Revolution of 1688, to which all these troubles of the seventeenth century

led—and then there opens up a brighter era for curlers, and for those who

did not curl. Those ancient worthies, who in the dark days cultivated the

culling art under difficulties now unknown to us-and who faithfully upheld

the cause •of curling till the clay of freedom, peace, and brotherhood saw

its recognition as a national game—will ever deserve honour from succeeding

generations of curlers; and none, we are sure, will grudge the little space

we have devoted to their memory.

In the same year in which allusion is thus made

to curling by Lord Fountainhall, we find a reference to the stone used in

the game, by Sir Robert Sibbald, M.D. (1639-1722), in his Scotia Illustrata

Sive Prodromus Historian Naturalis, published at Edinburgh in 1684. In Part

II. Book IV. Cap. III., p. 46, under the heading De Marmoribus, there occurs

the following in a list of different kinds of stone or marble to be found in

Scotland [It is not unlikely that this refers to the stone noticed by

Wallace in his work on Orkney, the reference to which comes next on our

list. Wallace's work was dedicated "To the much-honoured Sir Robert Sibbald

of Kipps, M. D.," etc., and in the dedication Wallace's son says, "It was in

compliance with your desire (when you were composing your Atlas) that my

father made this description, to give you an account of that countrey."] :-

"Lapis niger, quo super Glaciem luditur,

nostratibus a Curling stone."

The last reference of the seventeenth century

which falls to be noticed is found in an interesting and now very rare

little work, published by John Reid, Edinburgh, in 1693, and entitled—"A

Description of the Isles of Orly, ney, by Master Tames Wallace, late

Minister of Kirkwall. Published after his death by his son." At pp. 9-10 (In

the excellent reprint of this work, edited with notes by Dr Small, and

published by Brown, Edinburgh, in 1SS3. V. Chap. I. p. 11.¸) it is said-

"To the East of the Mainland Iyes Copinsha, a

little isle but very conspicuous to seamen, in which and in severell other

places of this Countrey are to be found in great plentie excellent stones

for the game called Curling."

In his Account of the Game of Curling (p. 23),

Ramsay gave this statement from Wallace's work as from Camden's Drittannia,

which was published as far back as 1607, and up till the year 1840 (Dr

Walker-Arnott of Arlary was the first to point out this mistake, in a

communication published by him in the Annual of 1840, though he also makes a

mistake in giving 1675 as the date of Gibson's translation of Camden,

instead of 1695. In the Annual of 1842 a Historical Sketch, drawn up at the

instance of the Committee of the Grand Club, appeared, and in

this—notwithstanding Dr Arnott's note—the old error is repeated (Ramsay, at

the Annual Dinner in 1844, also repeats the statement as to the mention of

the game by Camden in 1607). Dr Arnott complained to the Committee, and an

investigation into the subject was made. The Report of the investigation is

found in the Annual of 1847, signed by Professor Ferguson, and is decisive

as proving that Camden never mentioned the subject, but that, as noted

above, the passage was taken from Wallace's work, and inserted by Gibson in

his folio edition of Camden (1695), p. 1076. This incident in its early

history testifies to the usefulness of the Royal Club as a Court of Appeal

on all matters of interest to curlers.

In The Channelstane, Ser. III. pp. 58-62,

Captain Macnair has also very clearly pointed out the error regarding

Camden.) it was regarded by all writers on curling as the very earliest

historical reference to the game. This mistake seems to have arisen from the

fact that in 1695 an edition of Camden was published by Bishop Gibson

(Queen's College, Oxford), in which the statement occurs under "Additions to

the Orcades" (p. 1076), after the following explanation by the bishop (p.

1073) --

"The isles of Orkney are generally so little

known, and yet withal so lightly touched upon by our author [Camden], that

the curious must needs be well pleased to see a further description of them.

Mr James Wallace is our authority—a person very well versed in antiquities,

and particularly in such as belong to those parts, where his station gave

him an opportunity of informing himself more exactly."

Camden himself had no notice of the

curling-stones of Copinsha, and their testimony to the game has therefore to

remain in the background as belonging to the close of the century. Mr

Wallace does not tell us how far the "great plentie" availed to supply

curlers in these early times, when they did not think of rounding or

polishing the stones; but as doubts have been thrown upon the fitness of

such sea-boulders as were found at Copinsha, for use on the ice, (In the

minutes of the Clunie Curling Club, under date 5th Jan. 1830, we find that

in recognition of their kindness in presenting him with a "fluted kettle,"

Principal Baird had presented the members with a pair of the "Copinsha

stones," to be played for as a prize. In doing so he writes (Ap. 5, 1829)

"A book printed 150 years ago, says that the

best curling-stones were to be got at Copinsha, an island in Orkney. I

passed near it last summer on a calm day, and sent a boat on shore for

fourteen suitable blocks. They were brought on board accordingly, and were

landed here. From two of the best blocks I have got a pair of curling-stones

(and they are very

beautiful) made and handled. I shall beg the

club to accept of them as a present from me to be competed for on the ice,

and to become the prize of the best player."

How it fared with these prize stones in the

Clunic Club—whether they were useful as they were beautiful, we do not

discover, but the notices that here follow are not in their favour.

"'We also saw lately a pair of curling-stones,

belonging to Principal Baird, which he brought from the Isle of Copinsha,

interesting to curlers as being associated with the first historical notice

of the game. Camden is mistaken. however, in calling them `excellent'—for

upon trial, according to a well-known connoisseur, they are found to be `not

worth a rap."' —Memor. Curl. ifaben. p. 62.

"The ancient sports and pastimes of Scotland are

frequently referred to by our old historians and poets; but among these we

find no notice of curling till 1607, when Camden, in his Brittannia, in

reference to the Isle of Copinsha, as it were, incidentally alludes to the

game, from the circumstance of a peculiar species of rock found in that

place being, as he states, used in making stones to play the game, but which

rock has since been found to be useless for any such purpose—a circumstance

which satisfactorily shews that the people knew nothing about

curling-stones, or of the right metal required for the foundation of a

weapon of tough but friendly warfare. "—Curler's Magazine, Dumfries, 1542,

p. 6.)

we are not warranted in supposing that the Isle

of Copiiisha was the Ailsa ('raig of ancient curling, or that supplies were

forwarded from thence, to any great extent, to curlers in the South.

Wallace's statement may however, be held to prove that the game was known as

far north as Orkney in the end of the seventeenth century.

Between 1700 and 1800

the literary references to curling shew that it was generally practised

in Scotland. Several accounts of the came and of interesting bonspiels

are given; curling societies are formed; and curling is by the end of

the century entitled to be regarded as the great national winter game.

Ramsay, writing in 1811, says:-

"At Edinburgh, where curlers are collected from

all the counties of Scotland, this amusement has been long,, enjoyed. And in

so great repute was it towards the beginning of the last century, that the

magistrates are said to have gone to it and returned in a body, with a band

of music before them, playing tunes adapted to the occasion. Then it was

practised) chiefly on the North Loch, before it was drained, and at

Canonmills."

We find this statement repeated in all

succeeding accounts of the game, and it is highly creditable to the civic

dignitaries of the period to find that they gave such official patronage to

such an excellent and profitable amusement. It is a pity the old custom has

ceased. A minute search of the Town Council Records has given us no proof

that the magistrates gave such formal countenance to the game, but we see no

reason to disbelieve the statement. Up till the time of the Reform Bill of

1833, the Council Records, it seems, are very meagre. Processions on the

part of the Council were also commoner in those days than they are now, and

the Nor' Loch was a popular resort of the citizens in the time of frost. Sir

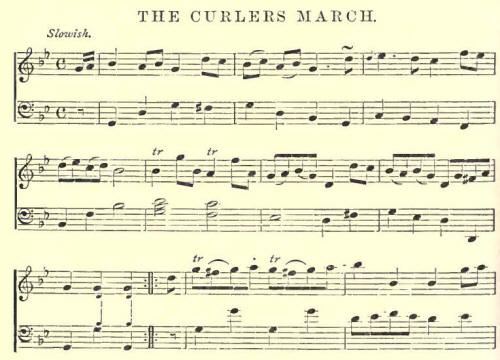

Richard Broun (Memorabilia, p. 62) supplements Ramsay's statement by saying

that on the occasion of the magisterial procession " the air played was The

Curlews March, since known by the name of The Princess Royal. In Songs for

the Curling Club held at Canonmills, to which we shall refer later on, the

first place is given to The Curlers March. Tune, Princess Royal. The March

is rather ponderous, but the enthusiasm of the "curling core" gives it

considerable animation, and it cannot fail to be interesting, as the

earliest curling song we meet with. The air Princess Royal may be recognised

as that to which the well-known naval song The Arethusa is sung. The music

of this song is generally ascribed to Shield, but as lie was not born till

1748 it is plain that this conflicts with Broun's statement that the air is

that to which the magistrates of Edinburgh marched in the beginning of last

century. The words of The Arethusa fix its date as not earlier than the end

of last century, as it describes a naval encounter with the French. We have

come to the conclusion that Shield was not the author of the tune, that lie

simply adapted it as he did in other cases (for in the operas which lie

wrote he was in the habit of introducing ancient or national melodies), and

that the music of The Princess Royal was really the property of the curlers,

and the accompaniment of their March. That it is the tune to which Broun

referred is proved by the fact that The Curlers March is suitable to it, and

probably to no other. Shield, as far as we can learn, never claimed it as

his. It is found in M 'Glashan's Collection, published in 1782. It is also

in Gow's Repository, (Gow's Repository of the Dance Music of Srotland,

Popular Edition (Book II. p. 45). Published by .John Purdie, Edinburgh.

Dedicated to the Duchess of Buccleuch by Neil Gov & Sons.) published in

1802, and as Shield was then alive it is very improbable that a few years

after the publication of The A.rdh tusa he would have allowed Neil Gow to

make use of an air composed by him, and to give it under a different iiaiiie

in a collection of the Dance Music of Scotland. (In the recollection of many

persons living the time as given in Gow often played as a country dance.) It

is only an act of justice, and one for which the brotherhood ought to be

grateful, that the tune should now be restored to its rightful owners, and

that the alliance between The Curlers March and The Princess Royal, for a

long time broken, should here be renewed. There is no difference between

this version from. Gow and that of Shield, except that in the latter a

change of key is necessary to adapt it to the pitch of the human voice, and

some slight simplification of the notes is needed to make it more suitable

for singing.

" Tho' Sol now looks shyly, and Flora is gone

To Mother Root's lodgings, of turf, mud, and stone,

Where they two together,

Throughout the hard weather,

Unsocial as Vestals, keep house quite unknown.

Unlike are the curlers, now more social grown—

Unlike to recluses who winter alone

With mutual friendship glowing, to action prone,

Forth come they

Brisk and gay,

All in flocks like sons of the spry,

Inspired by the sound of the curling-stone!

"Tho' hedges around us, and trees everywhere,

Their hoary heads shaking o'er their arms quite bare,

Are all in a quiver,

As cold made them shiver.

We curlers are sportive, and youthful our air.

Since Pan has afforded abundance of clothes,

And Ceres vouchsafes acquavit e and brose,

Who cannot very weII, with the help of those,

On ice stay

All the day

Cold and care both driving away

The name of a curler unwarily chose.

"Tho' quitting, and shaking her cold northern

nest

Of feather'd snows, where she long lay at rest

Her pinions awaiting

Mischief meditating

With hostile intent comes the full--fledg'd tempest.

To curlers determin'd their posts to maintain

And bravely resolv'd thro' a winter campaign

With hard fifty-pounders to answer again.

And to treat

Ev'ry threat

With smart repulse and contempt meet

Such impotent bluster seellls perfectly vain!

Then sally out boldly, and form round our ring,

Like waters in frost we together will cling,

To corn bat proud Boreas,

Or who else may shore us,

Until we shall meet the return of the spring.

Now mark the dread sound as our columns move on

So solemn, so awful, so martial 's the tone,

The clouds resound afar whilst the waters groan!

Stable rock

Feels our shock,

As if stern Mars in transport spoke--

Such the thunder and crash of the curling-stone`!

"Our exercise o'er, to headquarters away,

Where old sullen Night. seems young, cheerful, and gay;

Full-handed approaching,

Her rival reproaching,

Cries, eat, drink, laugh dead, illy young brother scrub Day.

The squint-ey'd churl now no longer is seen

Obey the command of the sable-clad queen—

Profusion's preceded by beef and green.

And the bowl,

Highland soul

Does all our cares and fears con trolll,

Whilst gleefully we drink—'To all Curlers keen!"'

This ponderous March, as an argument in favour

of the creditable custom of the civic rulers of Edinburgh in the early part

of the seventeenth century, has pushed itself forward among the references

now under notice. In the strict order of tune, the earliest allusion of the

writers of this century to curling is that of "the Laird of Romanno a quaint

physician named Pennecuik, who wrote verses," and published their in 1715.

(A Geographical, Historical Description of the shire of Tweeddale. With a

Miscelany and Curious Collection of Select Scottish Poems. By A. I. M.D.

Edin. 1715. The lines quoted are at p. 59 in The Author's .Answer to his

brother JPs many Letters, diswasing him from staying longer in the Country,

and inviting him to come and settle his residence in Edinburgh (Old Reekie).)

Alexander Pennecuik, M.D. (1652-1722), was evidently—like George Rutliven,

that ancient curling doctor of happy memory—a supporter of the game from a

medical point of view. He prescribes it for himself and his patients in

these words:—

"To Curie on the Ice, does greatly please,

Being a Manly Scottish Exercise,

It CIears the Brains, stirrs up the Native Heat,

And gives a gallant Appetite for Meat."

There we have the praise of curling in a

nutshell. "Curl," says the doctor, "and throw physic to the dogs." If

Peebles was not at the play in the time of Darnley, the folks of the

district evidently knew well the virtues of the game when the quaint

poet-physician lived among them two centuries ago. It is to be hoped that

they have not forgotten the old doctor's prescription, for it is a good one.

Allan Ramsay (1686-1758) clearly indicates that

curling in his time was recognised as the popular national winter game.

Allan spent his boyhood in a curling district —Craufurd floor. When he comes

to Edinburgh he makes archery his favourite amusement, and composes several

songs in its honour, but in the winter season he must have found time after

curling the wigs of the citizens, to have a curl with some of them on the

ice. It is more than likely that the poet knew the virtues of "Whirlie" (p.

38-9), for he must often have visited Sir John Clerk at Penicuik, (Ramsay

spent much of his time during his latter years with Sir John CIerk of

Pennycuik, and Sir Alexander Dick of Prestonfield, who courted his company;

because they were delighted by his facetiousness. Sir John, who admired his

genius and knew his worth, erected at his family-seat of Pennycuik an

obelisk to the memory of Ramsay.— The Life of Allan Ramsay. Preface to

Poems, 2 vols. Camden, CadelI, and Davies, 1880.) when curling was being

keenly carried on by the baronet and his neighbours. When he retired from

the Luckenbooths in 1755, to spend his declining years in the curious

octagonal mansion, which he had built on the Castle-hill, he must have heard

the roar of the curling core as they played on the Nor' Loch beneath, and

lie was not a curler if he kept the house on such occasions. It is true we

find the poet, after the magistrates have prohibited his playhouse in

Carrubbers' Close, in a metrical complaint to Lord President Forbes,

saying:-

"When ice and snaw o'ercleads the isle,

Wha now will think it worth their while

To leave their gowsty country bowers,

For the anes blythsome Edinburgh's towers,

Where there's no glee to give delight,

And ward frae spleen the langsome night

For which they'll now have nae relief,

But soak at haune, and cleck mischief."

(Gentleman's magazine, 1737, p. 507.)

Curling might, for all that, have been the

"glee" that gave delight to day: it was the dulness of the evening that

vexed the heart of honest Allan. There was then no Northern Club in the

city, with the electric light turning night into day for curlers, or Ramsay

might have been comforted by the curling-pond, when the theatre was denied

him.

In his Epistle to Robert Yarde of Devonshire,

the poet pursues quite a different strain. He writes to his friend:-----

Frae northern mountains clad with snaw,

Where whistling winds incessant blaw,

In time now when the curling-stare

Slides murmuring o'er the icy plat."

The dulness of the evenings is forgotten. With

curling bonspiels, and the happy feasts of fellowship that follow them,

winter in Scotland loses all its bitterness, and we can laugh in our

sleeve"`at the "gowks" who think that we are in misery during the frost, or

at any other time; indeed:-

"We wanted nought at a'

To make us as content a nation

As any is in the creation."

So it is now: so may it continue to be! Our

Scottish winter is delightful when we have our Scottish winter game. Allan

Ramsay was the first to celebrate the happy union, and we thank him for it.

In his poem on Health, dedicated to the Earl of

Stair in 1724, Ramsay has a good word to say of curling, as of other manly

games. Lethargus, the slothful, who "snotters, nods, and yawns " in his easy

chair close by the fire, is contrasted with Hilaris, the active, whose

constitution is braced by exercise, and made proof against the winter's

cold:—

"Free air lie dreads as his most dangerous foe,

And trembles at the sight of ice or snow.

The warming-pan each night glows o'er his sheets,

Then he beneath a load of blankets sweats

The which, instead of shutting, opes the door,

And lets in cold at each dilated pore

Thus does the sluggard health and vigour waste.

* * * * *

But active Hilaris much rather loves,

With eager stride, to trace the wilds and groves

To start the covey or the bounding roe,

Or work destructive Reynard's overthrow

The race delights him, horses are his care,

And a stout ambling pad his easiest chair.

Sometimes to firm his nerves, he'lI plunge the deep,

And with expanded arms the billows sweep:

Then on the links, or in the estler walls,

He drives the gowff or strikes the tennis-balls.

From ice with pleasure he can brush the snow,

And run rejoicing with his curling throw;

Or send the whizzing, arrow from the string—

A manly game, which by itself I sing.

Thus cheerfully he'll walk, ride, dance, or game,

Nor mind the northern blast or southern flame.

East winds may blow, and sudden fogs may fall,

But his hale constitution's proof to all.

He knows no change of weather by a corn,

Nor minds the black, the blue, or ruddy morn."

The poet's ideal of a healthy life is not,

however, complete. "Bodily exercise profiteth little" without the culture of

the mind, and so he wisely adds:-

"Here let no youth, extravagantly given,

Who values neither gold, nor health, nor heaven,

Think that our song encourages the crime

Of setting deep, or wasting too much time

On furious game, which makes the passions boil,

And the fair mean of health a weak'ning toil,

By violence excessive, or the pain

Which ruin'd losers ever must sustain.

"Our HiIaris despises wealth so won,

Nor does he love to be himself undone

But from his sport can with a smile retire,

And warm his genius at Apollo's fire

Find useful learning in the inspired strains,

And bless the generous poet for his pains.

Thus he by lit'rature and exercise

Improves his soul, and wards off each disease."

This complimentary reference by Ramsay to the

beneficial effect of the curling throw occurs at the close of the first

quarter of the century. It is close upon the beginning of the last quarter

before we find any other allusion to the game in our literature. Then, as we

have stated, curling; was fairly installed as our Scottish national winter

game, and ever since its progress has been remarkable. This long interval of

silence does not, however, imply that the amusement was neglected. We know

that it was not. It was a transition period in which the rough block was

gradually discarded, and the round stone brought into use. No mention is

made of it in the reign of George II. (1727-1760), but it must be remembered

that at that time the country was still disturbed by "civil disorder, and

political disaffections and antagonisms." With the final crushing of the

Jacobite Rebellion at Culloden, in 1746, the condition of the country admits

of the development of the game, which above all others is symbolic of

brotherhood, prosperity, and peace. The second and third quarters of the

eighteenth century may therefore be regarded as important in the history of

curling, though we hear so little of it at that time. John Frost seems to

have done all he could to advance the game, if we are to believe Andrew

Crauford's communication to Dr Cairnie, about a remarkable visitation of His

Majesty at Lochwinnoch and elsewhere.

"There was an extraordinary and tedious frost in

1745 or 1746. The inhabitants of the south side of the Loch walked over the

ice to the kirk on thirteen Sundays successively. The wells, fountains and

burns were dried up by hard frost. The people suffered great hardships. The

ice was bent, and bowed down to the bottom, because no water entered into

the Loch. The Curling ceased on account of the curve of the ice. James

Buntin of Triarne, Beith Parish (son of the Laird of Ardoch, Cardross

Parish, Dumbartonshire), was the father of Nicol Buntin, who lived in Beith,

and whose burial happened in this remarkable frost. The attendants at this

funeral had the drops from their noses frozen like shuchles (Anglice,

icicles). All events, through all the parishes surrounding Beith, for many

years subsequent to that frost, were dated from Nicol Buntin's burial."

It makes our teeth water to read of days like

these, and we may be sure that even in the most disturbed districts, curlers

would find times and opportunities for indulging in their amusement. Sir

Walter Scott, when he depicts the social life of this period in Guy

Mannering, does not omit to notice that even then curling matches were

common in Galloway, and the south of Scotland, in the age of Jacobites,

gipsies, and smugglers. Julia Mannering, as she confides the story of her

love to Matilda MSarchmont, suddenly introduces us to "a small lake at some

distance from Woodbourne now frozen over," and "occupied by skaters and

curlers, as they call those who play a particular sort of game upon the

ice":-

"The scene upon the lake was beautiful. One side

of it is bordered by a steep crag, from which hung a thousand enormous

icicles, all glittering in the sun ; on the other side was a little wood,

now exhibiting that fantastic appearance which the pine-trees present when

their branches are loaded with snow. On the frozen bosom of the lake itself

were a multitude of moving figures—some flitting along with the velocity of

swallows, some sweeping in the most graceful circles, and others deeply

interested in a less active pastime—crowding round the spot where the

inhabitants of two rival parishes contended for the prize at curling: an

honour of no small importance, if we were to judge from the anxiety

expressed both by the players and bystanders."

In the next chapter Jock Jabos informs us, at

the instance of Glossin, that auld Jock Stevenson was at the "cock" —i.e.,

was skip of one of the rinks—and that "there was the finest fun among the

curlers ever was seen" (though Harry Bertram was too concerned about the

said Julia to pay any attention to the bonspiel). In this pleasant peep of a

curling match in the middle of last century, Scott writes with the knowledge

that makes his romances as valuable for historical information as they are

interesting in themselves. The conditions were not yet such as permitted of

curling making extensive progress; but the game was generally practised, and

matches between rival barons, or between neighbouring parishes, were

becoming common. As will be seen in our next chapter, a good many clubs had

also by this time been formed, with the object of uniting curlers in

brotherhood, and advancing the progress of the game.

When Pennant passed through Eskdale and

Liddesdale the country of Dandie Dinmont—in the year 1772, gathering

information about the manners and customs of the different districts of

Scotland, and "takin' notes" with a view to "prent them," he must have

fallen in with some keen curlers, for it is here lie remarks, "Of the sports

of these parts, that of curling is a favorite." (For remarks relating to

Eskdale, Pennant was indebted to John Maxwell, Esq. of Brooinholme, and Mr

Little of Langholme.—Pennant's Tour, Vol. II. p. 4.) Cattle-lifting had

given way before curling, and the district was none the worse for the

change.

Pennant's description (vide p. 5 6) has

generally been quoted as the earliest, but this however appears to belong to

an account of the gave found in the Poem (Poems on Several Occasions. By

James Graeme. Edinburgh, 1773.) of James. Graeme (1749-1772), Graeme, who

was a student of divinity, and a native of Carnwath, Lanarkshire, died of

consumption at the age of 23, in the same season in which Pennant made his

tour; and the poems, which were written during his University holidays, were

published by his friend Dr Anderson in 1773, (Graeme's Poem on curling had

also been published anonymously in Ruddiman's Weekly Magazine. February

1771.) while Pennant's work was not published till 1774. The poetical merit

of this account of curling is not of the highest order, but the picture of

the brawny youth tugging the old channel-stave from the side of the loch

illustrates the ancient game, and the "hoary hero " fighting his battles

over again after the bon-spiel, is too faithful to be omitted. We therefore

give this earliest account as it is found at pp. 37--39 of Graeme's.

volume:---

CURLING: A POEM.

"Fretted to atoms by the poignant air,

Frigid and Hyperborean flies the snow,

In many a vortex of monades, wind-wing'd,

Hostile to naked noses, dripping oft

A crystal humour, which as oft is wip'd

From the blue lip wide-gash'd: the handing sleeve

That covers all the wrist, uncover'd else,

The peasant's only Handkerchief. I wot,

Is glaz'd with blue-brown ice. But reckless still

Of cold, or drifted snow, that might appal

The city coxcomb, arm'd with besoms, pour

The village youngsters forth, joinnd and Ioud,

And cover all the loch: With many a tug,

The poud'rous stone, that all the Summer lay

Unoccupy'd along its oozy side,

Now to the mud fast frozen, scarcely yields

The wish'd-for vict'ry to the brawny youth,

Who, braggart of his strength, a circling crowd

Has drawn around him, to avouch the feat

Short is his triumph, fortune so decrees;

Applause is chang'd to ridicule, at once

The loosen'd stone gives way, supine he falls,

And prints his members on the pliant snow.

The goals are marked out; the centre each

Of a large random circle; distance scores

Are drawn between, the dread of weakly arms.

Firm on his cramp-bits stands the steady youth,

Who leads the game: Low o'er the weighty stone

He bends incumbent, and with nicest eye

Surveys the further goal, and in his mind

Measures the distance; careful to bestow

Just force enough; then, balanc'd in his hand,

He flings it on direct ; it glides along

Hoarse murmuring, while, plying hard before,

Full many a besoni sweeps away the snow,

Or icicle, that might obstruct its course.

But cease, my muse! what numbers can describe

The various game? Say, can'st thou paint the blush

Impurpled deep, that veils the stripling's cheek,

When, wand'ring wide, the stone neglects the rank,

And stops midway? His opponent is glad,

Yet fears a sim'lar fate, while ev'ry mouth

Cries off the hog, and Tinto joins the cry.

Or could'st thou follow the experienc'd play'r

Thro' all the myst'ries of his art? or teach

The undisciplin'd how to wick, to guard,

Or ride full out the stone that blocks the pass?

The bonspeel oer, hungry and cold, they lie

To the next ale-house; where the game is play'd

A gain, and yet again, over the jug;

Until some hoary hero, haply lie

Whose sage direction won the doubtful day,

To his attentive juniors tedious talks

Of former times;—of many a bonspeel bain'd,

Against opposing parishes; and shots,

To human likelihood secure, yet storm'd

With liquor on the table, he pourtrays

The situation of each stone. Convinc'd

Of their superior skill, all join, and hail

Their grandsires steadier, and of surer hand."

Robert Burns (1759-1796) does not say much about

curling. To the everlasting regret of the brotherhood of the rink, our

national bard has not dedicated any special song of praise to our national

game. A bonspiel has not secured a place among his inimitable pictures of

rural life. There is a great deal about winter in Burns: the season seems to

have had a strong effect on his mind. It is not, however, the crisp frosty

day—so dear to curlers, when the air is clear and the ice is keen, that

delights the poet's heart: it is the wilder aspect of winter that affects

him, and this because it answers to his feelings:-

Come winter, with thine angry howl,

And raging bend the naked tree

Thy gloom will soothe my cheerless soul,

When nature all is sad like me!"

At the sound of "chill November's surly blast,"

he sings the dirge Ian was made to mourn; and in the sauce tender strain of

sympathy the "winter-night "-

"When biting Boreas, fell and doure,

Sharp shivers through the leafless bower,"

hears hint lamenting over the sufferings of

beasts and birds, and the sorrows of the poor and the oppressed. A peculiar

lustre has been shed on our national game by the sympathy and charity that

have always attended on it. Curlers in their winter amusement remember the

needs of the suffering poor. It is therefore the more surprising to find

that Burns in his tenderness of heart did not give its weed of praise to the

game which so happily combines benevolence with enjoyment. Curling does not,

however, pass unnoticed by our national bard. That it was the common game of

winter may be inferred from the first two lines of The Vision (1786):-

"The sun had clos'd the winter day,

The curlers quat their roarin' play."

That Burns knew the game, and that he understood

the value set by curlers on a good skip, may in the same way be inferred

from his Elegy on Tarn Samson (1786). Thomas was "one of the poet's

Kilmarnock friends—a nursery and seedsrnan of good credit, a zealous

sportsman, and a good fellow." He was still in the flesh when the poet,

following the example of Allan Ramsay and others, when they wished to honour

their friends, celebrated his virtues in an elegy. Amon; other virtues

Samson's prowess and reputation as a curler are thus referred to:-

"When winter muffles up his cloak,

And binds the mire like a rock;

When to the loughs the curlers flock