|

"The baby-figure of the giant

mass

Of things to come."

Troilus and Cressida, Act I.

Sc. iii.

"The channelstane,

The bracing engine of a Scottish arm."

Davidson.

"Loud throughout the vale the

noise is heard

Of thumping rocks, and loud bravadoes' roar."

Davidson.

"Now mark the dread sound as

our columns move on,

So solemn, so awful, so martial's the tone,

The clouds resound afar, whilst the waters groan

Stable rock

Feels our shock

As if stern Mars in transport spoke

Such the thunder and crash of the curling-stone."

Canonmills "Curler's March,"

1792.

UR

enquiry into the origin and antiquity of curling brought its into contact

with a controversy about words. Our next chapter is a case of "sermons in

stones." Of crainpits, brooms, and other minor implements used in the early

game, there are few relics to be considered; but the different stages in the

development of curling are distinctly traced by the monumental stones that

have been brought under notice, especially since the formation UR

enquiry into the origin and antiquity of curling brought its into contact

with a controversy about words. Our next chapter is a case of "sermons in

stones." Of crainpits, brooms, and other minor implements used in the early

game, there are few relics to be considered; but the different stages in the

development of curling are distinctly traced by the monumental stones that

have been brought under notice, especially since the formation

of the Grand Club in 1818. Of these we have three types or varieties

distinctly marked, in the examination of which we are able to trace the

progress of the game. These types are:-

(1.) The KUTING-STONE, KUTTY-STANE, or PILTYCOCK.

(2.) The ROUGH BLOCK (with handle).

(3.) The POLISHED and CIRCULAR, STONE.

FIRST TYPE: THE KUTTING-STONE.—Curling,

when first practised, appears to have been a kind of quoiting on ice. The

stones had no handles, but merely a kind of hollow or niche for the finger

and thumb of the player, and they were evidently intended to be thrown, for

at least part of the course, the rink being shorter than it is now. III

handling these stones, it seems natural to infer that they were riot

delivered after being drawn straight back, but swept round from behind, and

sent toward their destination by a carving sweep. As might be supposed, they

were much smaller than stones of the handle type, minting front 5 or 6 to 20

or 25 Ibs. in weight. They would seem to have been picked up from the

channels of the rivers (Hence the term channel-stanes, though this may have

been given to them because of the channel or hove made for them in their

course on the ice). Mactaggart, in his amusing work, [The Scottish

Galloridian Encyclopedia (1824), 1). 130.] says that "when curling first

began it was played with flat-stones or loofies." [Loofie, a flat or plane

stone resembling the palm of the hand. Gall. Jamieson's Dictionary.] We have

seen that kuting and kluyten, the Dutch name for a game on ice, are not the

same word; but that curling, though now more allied to bowls or billiards,

did at first more nearly resemble the ancient galilie of quoits cannot

reasonably be denied. The Ettrick Shepherd, in his famous song, contrasts

the two gauzes thus:

I've played at quoiting in my day,

And maybe I may do 't again -

But still unto myself I'd say

This is no the channel-stane."

But it is certain that the word coiling, kuting,

or quoiting, was for a long time the word in common use to describe the

game, and in some districts it is still applied to it. Thus writes the

curling-poet of Chryston, W. Watson:-

The loch's aye the loch, whaur in cauld days o'

yore,

The lee-side was cheered by the quoitin-stane's roar,

Whaur aft our auld daddies wad off wi' their plaidies,

As they had been shown by their daddies afore."

And Grahame of "Sabbath" fame, at an earlier

date speaks of: "The

player as he stoops to lift his colt."

Andrew Crawfurd of Lochwinnoch, in a letter to

Cairnie in 1833, writes thus about a certain ice-hero:-

"Old Will M'Adam was a famous culler; he was

once in a bonspeil between the Glen and the Muirland conjoined against the

Brig-o'-Weir quoiters, with 14 a side. M'Adam was a very ugly man (like the

devil) in countenance. But he was an ingenious Man, up to the craft of

mounting of all manner of weaving work: he was a grand quoiter, he never

missed a shot; he was dignified by the Brig-o'-Weir folk with the

appellation of a warlock."—Cairnies essay, p. 93.

Sir Richard Brown, in his interesting

Memorabilia, calls curlers "the merry handlers of the quoit;" and at p. 103

he gives a letter from Principal Baird to, the Duddingston Club in 1822, in

which the Principal presents the club with "five stones, as specimens of the

original or earliest form of curling or coiting stones" which had been

recovered, one from a loch at Stirling, and four from the loch of Linlithgow.

"The stones, as will be seen, are from three to

four inches in thickness —of rather an oblong shape, and thinner towards the

point extremity. At the opposite and thickest extremity, there is on the

bottom (which has been artificially made quite smooth) a long thin hollow

cut out for admitting the fore part of the player's fingers: and on the

upper side of the stones there is a small hole for the point of the thumb.

From this form," the Principal goes on to remark, "it appears that the stone

has been coited or thrown by the hand to a short distance on the ice: if

thrown with force, and rightly floored, it must have been capable of being

propelled a very considerable length."

There are no dates on these stones, and Sir

Richard propounds a query in regard to their antiquity which it was

impossible at that time to answer. It was suggested by the following

discovery that had then just been made of a very ancient stone of the Second

type:- "Last week,

while the foundation of the old house of Loig, in Strathallan, was being dug

out, a curling-stone of a very different shape and texture from those now

generally in use in that district, was discovered. It is of an oblong form,

and had been neatly finished with the hammer. The initials `J. M.' and the

date 1611 are still distinctly legible, having been deeply though uncouthly

engraved. This discovery affords a curious and striking proof of the

antiquity of the name of curling."—Caledonian Mercury, 20th Dec. 1830.

Sir Richard's query was thus put:—"If a

curling-stone of an oblong form, `neatly finished with the hammer,' gives

the date 1611, what date will the pilty-cocks or kutingstones give?" For a

long time it was supposed that the oldest stone was that noticed in the

Annual of 1841, p. 11

"This last summer a curling-stone has been found in an old curling-pond near

Dunblane, bearing date 1551. It is 10 inches broad by 11 long and 5 thick,

and seems to have been taken from the bed of the river, and not to have been

dressed. There are two holes for the handle, as in the close-handled stones

still preferred in the district."

This Dunblane stone, it will be noticed, though

of very ancient date, is not of the primitive type, and it did not furnish

the answer to the query of Sir Richard Broun. It is only recently that a

kuting-stone, of date 100 years earlier than the Strathallan stone, has come

to light, and the Dunblane stone, so long supposed to be the most ancient,

has had to retire from the field. Not content with the custodialship of the

relics. of Sir William Wallace, Stirling, it would appear, now claims the

honour of guarding the most ancient relic of early curling.---

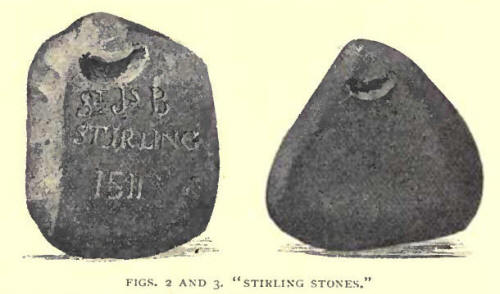

"In the Macfarlane Museum, Smith Institute, are

two old curling or rather kuting stones, one of which bears a date showing

it to be the most ancient stone in Scotland which has yet been discovered.

In shape this stone is nearly an oblong square, the sides being straight and

the top and bottom slightly rounded. The length is 9 inches, width 7½

inches, depth 4 5/8 inches, measurement round the middle 24 incises,

vertically 26 inches, and its weight 26 lbs. The hollow for the thumb is 1½

inches wide at the mouth, while the place for the fingers, which is

carefully carved, is 3½ inches long. On the upper side of the stone a small

space has been polished to receive the inscription, in Roman capitals, A

GIFT. while on the sole, which has been smoothed for the purpose, is the

following:- `ST Js B

STIRLING 1511.'

[It is right to note that the figures on this

stone are certainly not as old as they make out the stone to be. Dr Anderson

is of opinion that they have been cut out as late as the present century.

This does not, of course, disprove the antiquity of the stone, but tends to

cast a doubt upon it.]

"It can only be surmised that ST Js stands for `St James,' a popular saint

in Stirling, and B may be a contraction for ` Bridge' (or Brotherhood.'] It

is known that there was a St James' Hospital at the Bridge-end of Stirling

prior to the Reformation. The stone is made of blue whinstone, similar to

that of Stirling Rock, and having been a gift, it may be accepted as a fine

specimen of the curling-stones of the period.

"The other stone in the Smith Institute is of

the same material, but has the appearance of being older and more primitive,

and may have been originally a water-worn boulder taken from the bed of some

stream. Its shape is triangular, the sides and angles being rounded. It is

8¼ inches in length, and about the same in width, depth 4 inches,

circumference 22 inches, and weight 15 3/4Ibs. The thumb-hole and

finger-catch are roughly cut. A search through the records of the Museum has

failed to elicit any information regarding the history of these stones."

The above account of the remarkable relics

(Figs. 2 and 3) is given by Captain Macnair, in his interesting collection

of curling-lore [The Channel Stane. Fourth series, p. 66. The stones

themselves have, however, been specially sketched by our artist for this

work.] and is here reproduced by his permission. The present curator of the

Museum, Mr Sword, tells us that the stones are much prized, and carefully

preserved in a glass case, and that no further information regarding their

history has yet been furnished. It will be observed that one of the stones

referred to by Principal Baird was also found at Stirling, which evidently

bears the palms of antiquity. Thus, when Buchanan (who was a Stirlingite,

and is said to have written his History of Scotland at Stirling) was only a

boy of five, we have it proved that our national game was in existence at

his native place, though not worthy of notice afterwards by him or any other

historian of the time. We had the pleasure of seeing the Stirling stones in

the great Exhibition at Glasgow, 1888, where they were exhibited alongside

the no less venerable relics of our old archery and golf clubs in that

wonderful antiquarian temple—the Bishop's Palace and it is needless to say

that they were viewed with great interest by all curlers. At the same

Exhibition, on the stand of T. Thorburn, Leith, where the beautiful symmetry

and polish of the modern stones of this celebrated maker stood out in

striking contrast to their venerable forbears, the Marquis of Breadalbane

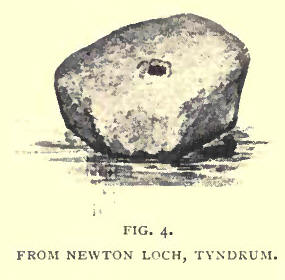

exhibited a pair of old stones [These stones were also exhibited at the

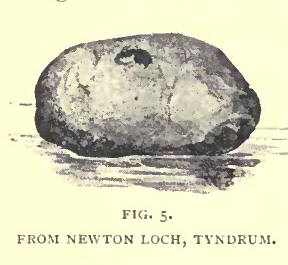

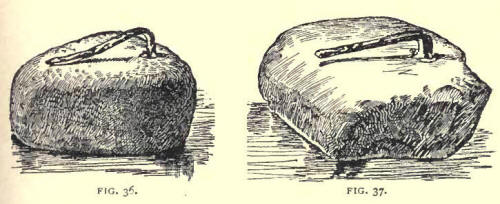

Jubilee Dinner of the R.C.C.C., Nov. 28, 1888.] (Figs. 4 and 5) which were

taken about thirty years ago out of Newton Loch, a mile below Tyndrum, while

it was being partially drained to make it safer as a curling-pond.

The

Marquis rightly regarded "the channel-stanes" as precious, insured them in

transit for £25; and they were laid aside with proporionate care at Glasgow

station, till it was almost too late for their entry at the Exhibition. A

porter was sent off at steam-speed with what he was taught to regard as a

valuable burden. He succeeded in reaching the place in time, and, with the

sweat streaming down his face, he watched the opening of the heavily-insured

box. Imagine his disgust when he saw what, in his eyes, were only two old

useless "blocks" turned out. The

Marquis rightly regarded "the channel-stanes" as precious, insured them in

transit for £25; and they were laid aside with proporionate care at Glasgow

station, till it was almost too late for their entry at the Exhibition. A

porter was sent off at steam-speed with what he was taught to regard as a

valuable burden. He succeeded in reaching the place in time, and, with the

sweat streaming down his face, he watched the opening of the heavily-insured

box. Imagine his disgust when he saw what, in his eyes, were only two old

useless "blocks" turned out.

It

was too much for the poor fellow, and, in wrath, he thereupon uttered words

such as railway porters in our country are unfortunately too often heard to

utter, with less excuse. The stones which have so much to answer for are, no

doubt, very old; but as they are without date, we are left to conjecture

regarding them. Though they are about the weight of the early kuting-stones,

yet, as the holes in them are evidently not for the insertion of fingers or

thumbs, but for handles, they probably belong to a later period than the

Stirling stones. This is borne out by the fact that, along with them were

other stones, with iron handles almost rusted away, which have since been

lost sight of. This much is, however, proved by these interesting relies

that curling was once enjoyed in certain districts from which it has quite

disappeared. When the Breadalbane, Strathfillan, and Glenfalloch Club was

instituted in 1858, the people, we are told, were astonished to see the new

game; and an old lady, who died about six years ago, aged over 100 years,

had never seen or heard of such a game. An interesting point in connection

with this, as pointed out by Mr R. Macnaughton, Comrie, is that nearly as

far back as the middle of last century the game must have been played in

some parts of the Highlands, though there are some who think that it had not

at that time got beyond the Lowlands. It

was too much for the poor fellow, and, in wrath, he thereupon uttered words

such as railway porters in our country are unfortunately too often heard to

utter, with less excuse. The stones which have so much to answer for are, no

doubt, very old; but as they are without date, we are left to conjecture

regarding them. Though they are about the weight of the early kuting-stones,

yet, as the holes in them are evidently not for the insertion of fingers or

thumbs, but for handles, they probably belong to a later period than the

Stirling stones. This is borne out by the fact that, along with them were

other stones, with iron handles almost rusted away, which have since been

lost sight of. This much is, however, proved by these interesting relies

that curling was once enjoyed in certain districts from which it has quite

disappeared. When the Breadalbane, Strathfillan, and Glenfalloch Club was

instituted in 1858, the people, we are told, were astonished to see the new

game; and an old lady, who died about six years ago, aged over 100 years,

had never seen or heard of such a game. An interesting point in connection

with this, as pointed out by Mr R. Macnaughton, Comrie, is that nearly as

far back as the middle of last century the game must have been played in

some parts of the Highlands, though there are some who think that it had not

at that time got beyond the Lowlands.

At Linlithgow we seem to have evidence of an

unbroken connection between the ancient and the modern game. From the same

loch that now resounds with the "roar" of many a keen battle, and which Lees

has immortalised by his famous painting of the Grand Match of 1848, several

samples of the old finger or kuting-stone have been recovered. Some of

these, as we have seen, were given by Principal Baird to the Duddingston

Club in 1822, but of their present existence we have no intelligence. Mr W.

H. Henderson informs us that about twenty-five years ago a kuting-stone was

sent by him from Linlithgow to the Antiquarian Museum, Edinburgh. From the

description furnished by him, this stone must have been a good specimen of

the earliest type; but the Linlithgow relics seem to be unfortunate in their

destiny, for, after diligent enquiry, we have been unable to find any trace

of this stone. In the Museum there are, however, two specimens of the

earliest type of stone. One of these is the smallest we have seen, and is

much like an ordinary paving-stone. It was found embedded in the wall of an

old house in the High Street, Edinburgh, which was being demolished some

years ago, and brought by a workman to the Museum. Dr Anderson tells us that

he was at first inclined to regard it simply as a disused cobbler's lapstone,

but the marks for finger and thumb led him to suppose that it was a kuting-stone,

and there is little doubt that he is right in his supposition. That such a

stone should have been found in such a place is very remarkable, and may

suggest to Edinburgh curlers a claim of antiquity for the game on the Nor'

Loch that they have not as yet put forward.

Of the antiquity of curling in the Galloway

district we have several proofs in the form of loofie-stones, as they are

called by Mactaggart. The late Rev. G. Murray of Balnaclellan had a good

specimen among his collection of curling curiosities—"flat and wedge-shaped,

with places for the fingers on one side and for the thumb on the other." The

stone is now to be seen at his sister's house, Meadowbank, New-Galloway. A

similar stone is the property of a merchant there—P. Mackay. Two of these

ancient stones are also to be found in the Museum at Kirkcudbright, of which

Mr M`Kie is curator. They were found in Loch Fergus.

The

Doune Club have in their possession a good specimen of the Kuting-stone. It

was found some years ago in digging up the foundation of an old house in

Doune, which stood on a feu dating from 1664. It is a flattish, smooth

whinstone nearly circular, a little rounded on the top with flat bottom. It

is about 8½ inches in diameter, and weighs 14½lbs. The upper edges are a,

little clipped to give it proper shape, otherwise it has its natural smooth

surface. It has no handle, but has a hollow for the thumb, and a catch

underneath for the fingers. The

Doune Club have in their possession a good specimen of the Kuting-stone. It

was found some years ago in digging up the foundation of an old house in

Doune, which stood on a feu dating from 1664. It is a flattish, smooth

whinstone nearly circular, a little rounded on the top with flat bottom. It

is about 8½ inches in diameter, and weighs 14½lbs. The upper edges are a,

little clipped to give it proper shape, otherwise it has its natural smooth

surface. It has no handle, but has a hollow for the thumb, and a catch

underneath for the fingers.

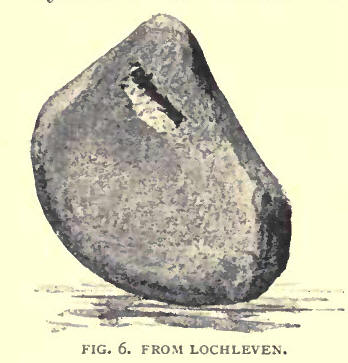

Lochleven, like Linlithgow, seems to have an

unbroken record; and no doubt the game has had there a "local habitation" as

long as in any other part of Scotland. Wyntoun, the author of our first

national history--the Orygynall Chronykill of Scotland, was Prior of St

Serf's Inch, Loclileven, in the end of the fourteenth century; and it may

yet appear that he heard the boom of the channel-stane in the silence of the

monastery, but he makes no complaint about it, and most likely it was not

such a roaring game at that time as to disturb the Prior at his "Chronvkill."

That it was played on Lochleven from time immemorial is, however, abundantly

evident. Alongside of the small High Street stone there is a larger-sized

specimen of the Kuting-stone (Fig. 6) lent to the Antiquarian Museum by D.

Marshall, F.S.A., to whom it had been gifted by L Wylie, shoemaker, Kinross.

It was got out of Lochleven about fifty years ago, and for the most of that

period dial duty, like its neighbour, as a cobbler's lapstone. This Kinross

stone is of whin, flat in appearance and triangular in shape.

"In its general contour," says Mr Burns Begg,

"it may be said to resemble a small but thick Belfast ham, with the

shack-bone somewhat shortened. It never has been graced with a handle of any

kind, but it has on its lower side or sole an oblong hollow hewn out for the

accommodation of the fingers of the player, while on the upper side there is

a corresponding hollow for the thumb. The stone shows no trace of ever

having been polished artificially, but has been worn smooth by the action of

the water in the channel out of which it was taken."

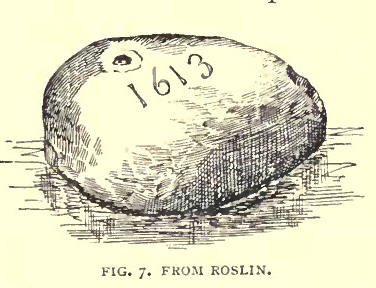

It

is stated in a Montreal paper (V Annual 1885-6.) that the Club there has in

its possession, among other historical relies, an ancient Kuting-stone found

at Roslin in 1826, and dated 1613, which was presented to them by the late

Dr Sidey. If the drawing which accompanies the statement is correct there

must be some mistake, or the Dr must have played a cruel joke upon his

Transatlantic "brithers," or the Annual of 1843 must have given a false

drawing; for, while this latter is reproduced here (Feb. 7), the Montreal

drawing is that of an ordinary handled block of the second type, in shape

like the Jubilee stone. A very good sample of the Kuting-stone, dated 1611,

is claimed by Torphican, where it was found in 1840 built in a wall, and a

notice of which appeared in the Annual of 1843 by Mr Durham Weir. It is of

grey whin, and the notch for the finger is 4 inches in length by 1 3/4

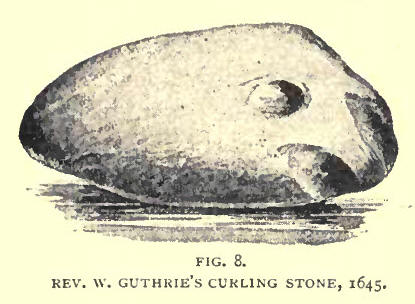

inches in depth. The curling-stone of the Covenanter Guthrie (Fig. 8), still

preserved in Craufurdland Castle, is also a legitimate type of the early

stone, though it must have been in use after 1644, when Guthrie was ordained

Minister of Fenwick. It

is stated in a Montreal paper (V Annual 1885-6.) that the Club there has in

its possession, among other historical relies, an ancient Kuting-stone found

at Roslin in 1826, and dated 1613, which was presented to them by the late

Dr Sidey. If the drawing which accompanies the statement is correct there

must be some mistake, or the Dr must have played a cruel joke upon his

Transatlantic "brithers," or the Annual of 1843 must have given a false

drawing; for, while this latter is reproduced here (Feb. 7), the Montreal

drawing is that of an ordinary handled block of the second type, in shape

like the Jubilee stone. A very good sample of the Kuting-stone, dated 1611,

is claimed by Torphican, where it was found in 1840 built in a wall, and a

notice of which appeared in the Annual of 1843 by Mr Durham Weir. It is of

grey whin, and the notch for the finger is 4 inches in length by 1 3/4

inches in depth. The curling-stone of the Covenanter Guthrie (Fig. 8), still

preserved in Craufurdland Castle, is also a legitimate type of the early

stone, though it must have been in use after 1644, when Guthrie was ordained

Minister of Fenwick.

The

period in which this Kuting-stone, Kutty-stane, Piltycock or Loofie was in

use may therefore be put down as extending from the beginning of the

sixteenth to. the middle of the seventeenth century (1500 - 1650); though in

that time we have also proof of the second or handled type of stone. From

their construction it is evident that early curlers coited or skvyted the

stone along the ice; but as to the style of the primitive game little

further can be inferred. If further light is to be thrown on ancient curling

it is in this direction more than the etymological that we look for

information; and certainly, until specimens of these curious stones are

found in other countries, we are entitled to hold that the game is

indigenous to Scotland. No doubt other and earlier ones will be found, [For

an Account of the latest, see note p. 47 under Strathallan.] for the loofie

oracle has not spoken its last word at Stirling, Linlithgow or Lochleven;

but Curling antiquaries will do well on this point to remember Aiken Drum's

Lang Ladle, for Curling Clubs are keen to make it clear that the most

ancient relics are in their keeping, and some of them, after paying for the

Praetorium of an old Kitting-stone, may meet with an Edie Ochiltree to take

away their jov. [It is not a little curious to find that Quoiting and

Curling have resumed their early relationship among our Kinsmen "across the

pond." In the admirable Annual of the Grand National Club of America there

is published each year, alongside of the Rules of Curling and the bonspiels

of States' curlers, an account of a great contest held each year for a Quoit

medal with "Rules for Quoiting." In the days of the old Huddingston Society

the members also got up quoiting matches to bring them together in the

summer season.] The

period in which this Kuting-stone, Kutty-stane, Piltycock or Loofie was in

use may therefore be put down as extending from the beginning of the

sixteenth to. the middle of the seventeenth century (1500 - 1650); though in

that time we have also proof of the second or handled type of stone. From

their construction it is evident that early curlers coited or skvyted the

stone along the ice; but as to the style of the primitive game little

further can be inferred. If further light is to be thrown on ancient curling

it is in this direction more than the etymological that we look for

information; and certainly, until specimens of these curious stones are

found in other countries, we are entitled to hold that the game is

indigenous to Scotland. No doubt other and earlier ones will be found, [For

an Account of the latest, see note p. 47 under Strathallan.] for the loofie

oracle has not spoken its last word at Stirling, Linlithgow or Lochleven;

but Curling antiquaries will do well on this point to remember Aiken Drum's

Lang Ladle, for Curling Clubs are keen to make it clear that the most

ancient relics are in their keeping, and some of them, after paying for the

Praetorium of an old Kitting-stone, may meet with an Edie Ochiltree to take

away their jov. [It is not a little curious to find that Quoiting and

Curling have resumed their early relationship among our Kinsmen "across the

pond." In the admirable Annual of the Grand National Club of America there

is published each year, alongside of the Rules of Curling and the bonspiels

of States' curlers, an account of a great contest held each year for a Quoit

medal with "Rules for Quoiting." In the days of the old Huddingston Society

the members also got up quoiting matches to bring them together in the

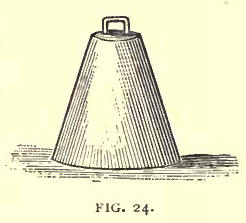

summer season.] SECOND

TYPE: THE ROUGH BLOCK.—

Of the description of stone that marks the

second stage of ancient curling, there are innumerable specimens "of all

sorts and conditions." An ordinary human being when he gets a handle to his

name is thereby lifted into greater importance, and certainly acquires more

power if he makes a proper use of his title; so, when the leverage of a

handle was applied to the channel-stare it completely left behind the puny

piltycock, and developed enormously in bulk and weight. In its development,

however, it did not follow the curves of the beautiful. Another century and

a half must elapse before the rough block is lien into proper form, and the

curler realises that scientific skill is higher than brute force. The

corners have to be rubbed off, the angularities have to be rounded, the wild

diversity has to be reduced, and it takes time to do it. Yet, withal, this

bulging, unshapely, heterogeneous age of the curling-stone, when the

curler—ender the newly-gotten power of the handle—took the hinge from the

gate-post, soldered it into the big boulder, bent incumbent under the

weight, swung the block in air, and hurled it up the rink with giant

strength, is an interesting one. "All affectation of minute accuracy," some

wise writer says, "in cases where in the nature of things accuracy is

impossible, is always a suspicious feature in a historian." In dividing our

study of stones as we have done, we do not presume to draw a distinct

line--saying here the Handle type begins and there the no-handle type ends.

The Dunblane stone and the Tyndrum stone, while veritable loofies in other

respects, had evidently been played with handles in the period of our

handle-less type of stone. Sometimes, as we shall see, the handle was an

after-addition to an old stone that had been played without it; and it is

plain that handles were in use before the finger-and-thumb stone was

discarded. We find also among stones of the later period many as diminutive

as any of the Kutty-stanes, their weight being under 20 lbs., pigmies among

the giants. This granted, we can, however, mark off a second period of 150

years, from about the middle of the seventeenth century on toward the end of

the eighteenth, when the stone in common use was in some respects as unlike

the early Kuting-stone, as it is to its polished and aristocratic descendant

of modern times. In this period stones (and handles also) were of infinite

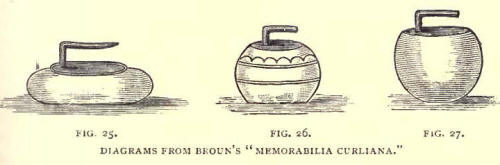

variety and shape. Sir Richard Broun (p. 42), in describing those in use at

Lochmaben, describes generally the stones of the period.

"They were of a wretched description enough.

Most of them being sea-stones of all shapes, sizes, and weights. Some were

three-cornered, like those equilateral cocked hats, which our divines wore

in a century that is past—others like dicks—others flat as a frying pan.

Their handles, which superseded holes for the fingers and thumb, were

equally clumsy and inelegant: being malconstructed resemblances of that

hooknecked biped, the goose."

Wretched as they may be, and useless for all

practical purposes in modern curling—as much behind our modern Ailsa. or

Crawfordjohn as the flint-lock of Marston Moor and Culloden is behind the

modern Martini-rifle; Yet nowadays, when the Zeitgeist of historical

research is at work everywhere, Curling Clubs vie with each other in

collecting from out-of-the-way corners these uncouth stones of other days.

Time was when little respect was shewn to them—when they had to do duty as

weights for weavers' looms and thick-ropes and cheese-presses, or lie

neglected among the rubbish at the back of the curling pond; but now they

are sought after, and, when found, readily elevated to places of honour.

Many, alas have met with the fate of "Whirlie," so pathetically described by

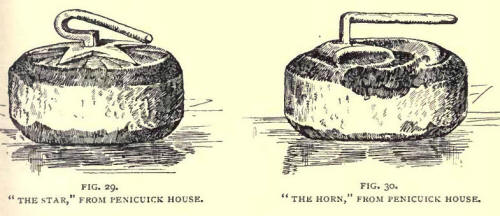

J. J., a member of the Penicuick Club in the Annual of 1847.

"Whirlie" was of oblong triangular shape, and

altogether a curling stone of nature's own making, being untouched with the

workman's hammer, except the hole in which the handle was inserted. It was a

jet black whin, and the sole, altogether a natural one, was very smooth,

which, with the dense and fine quality of the stone, made it a keen runner

even on dull soft ice. Tradition states that it was the favourite stone of

Sir John Clerk, one of the Commissioners of the Union, but nothing is

transmitted regarding its previous history. It was the first stone which the

writer of this ever played with, when but a very young lad about fifty-five

years ago; and we have never forgot the diversion which our youthful play

and this ancient stone afforded to both curlers and spectators. It being our

first attempt at curling, we were appointed to lead, which we happened to do

in such a manner that Whirlie was uniformly laid on or near the Tee; to

remove it from that position on which it had taken rest was no easy matter,

because, should the stole which was destined to remove it strike any one of

the angled corners, round went Whirlie, round and round, without ever

shifting from its position, while the stone which struck it went at right

angles across the rink. Stimulated with the success of our first attempt at

curling, we were early next day on the field of action with Whirlie in our

hand. But to our utter disappointment, poor fellow, a Curling Court was held

upon him, and he was unanimously condemned to perpetual banishment, or

rather to solitary confinement. This, however, we could not stand. We got

him mounted in a more modern and fashionable uniform, by rounding his more

acute angles, and in this capacity we introduced him as a stranger on his

ancient domain. A bad character and bad habits, however, have a mark put

upon them, and are not easily surmounted. The rogue, in spite of all our

endeavours, was still seen in his new shape and in his habits likewise, for

his roundabout way of going to work never forsook him, and again and again

has lie been banished from, and restored to the society of his fellows;

until at last we had the galling mortification to hear his final doom

decreed by the present Baronet, that this favourite stone of his illustrious

ancestor should be played with no more. Since then the Ice, and all the

curlers, except ourselves, who well knew him once, know him no more, and

perhaps for ever. But many are the lingering emotions of fond affection with

which we have sought after him; nor will we desist from the search until we

in our turn shall be consigned to oblivion. But should we have the good

fortune to find him, he shall have a `museum' for his abode, and be

henceforth preserved as an "Ancient Curling curiosity."

"Whirlie" is a type of inane in appearance and

in habits, and we are afraid in destiny also; but "the lingering emotion of

fond affection "that followed him to his unknown bourne now protects

hundreds of his contemporaries from such an unwished-for ending to their

curling career; and as the Royal Club, in its year of Jubilee, has decided

to form a collection of historical relics such as these, curlers will

by-and-bye have an opportunity of meeting face to face many of these brave

old warriors, and many that now lie outcast and neglected will, it is hoped,

be rescued from oblivion. It is not in the power of every club to secure

such specimens, but those that have them ought to be proud of them. From

returns furnished to us we give the names of some of the clubs that either

possess or can account for old curling-stones of the second period, and

statements regarding them, which will demonstrate forcibly what we have said

as to the variety in weight and appearance of these rude engines of ancient

curling warfare.

ABERDOUR.—Some stones, with fixed iron handles, are in the possession of the

Club, which weigh 83 lbs. each.

ALLOA—PRINCE OF WALES.—Two very ancient stones

were found when cleaning Ardoch pond about ten years ago. They are in the

hands of the President, Alexander Gall.

ALYTH.—The Secretary of this Club (J. Ferrier)

says: "The curlers in olden times took the stones as they got them from the

bed of the stream or the hillside, and all the workmanship bestowed on them

was the fixing of a bent Piece of iron into each as a handle. The forms of

the stones generally suggested the names of them. There were `Rockie,' 'The

Goose,' 'The Deuk,' &c., &c. In these clays curlers must have been powerful

men, for the stones were very heavy and none of the keenest. Instead of a

house, the curlers had only a small piece of ground fenced in with a rough

paling; in the form of a circle, and in the centre the stones were all

tumbled together in a heal). This looks as if the Druidical circle had still

been held in reverence among them."

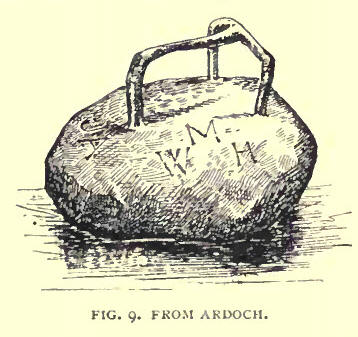

ARDOCH.—Several stones were dug out of a pond on

the estate of Mr Drummond Moray when it was drained some years ago. One

(Fig. 9) is dated 1700, and is lettered A. W. H.

In

the interesting records of the Muthill Club, which go back to 1139, we find

the first name entered "The Rev. Mr William Hally, Minister, Muthill," and

this stone is supposed to have belonged to him, he being the first minister

at Muthill after the abolition of Episcopacy in 1690. In

the interesting records of the Muthill Club, which go back to 1139, we find

the first name entered "The Rev. Mr William Hally, Minister, Muthill," and

this stone is supposed to have belonged to him, he being the first minister

at Muthill after the abolition of Episcopacy in 1690.

This stone is unique in its way, having a three

- legged handle inserted into it. It has now become the property of the

Royal Club, having been gifted by J. M`Callum, Braco.

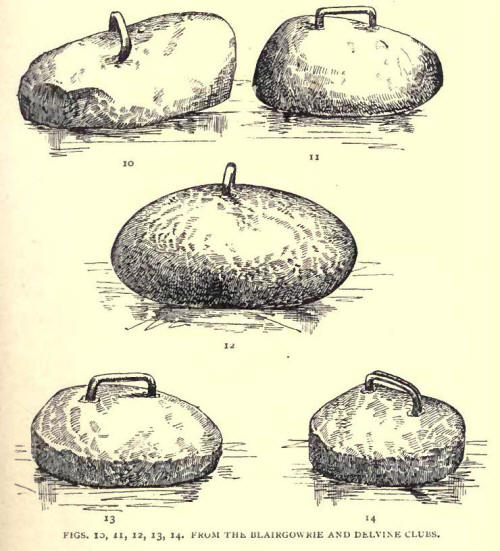

BLAIRGOWRIE and DELVINE Clubs both claim an

interest in the set of ancient stones here presented, these having, we are

informed, been formerly in the keeping of Blairgowrie, but presented or sold

to the Delvine Club, in whose custody they have been for many years. Fig.

10, "The Soo," weighs

79 lbs., and measures 161 x 11 inches. Fig. 11 is "The Baron," weighing 88

lbs., and measuring 14½ x 14 inches. Fig. 12 is called "The Ego," and weighs

115 lbs. It measures 17 x 12 inches. Fig. 13, "The Fluke," weighs 52 lbs.

and measures 12½ x 11 inches. Fig. 14, "Robbie Dow," weighs 34 lbs. and

measures 9 x 9 inches. This last and least was called after one of the Baron

Bailees, a, son of the parish minister of the time. They were all doubtless

taken in a natural state from the famous Ericht Channel, and they seem to

have done a good deal of work in

the hands of their strong masters. Their double

handles are noticeable. A metrical account of these and others is found in

Mr Bridle's Centenary Ode of the Blairgowrie Club:-

"In early years the implements were coarse,

Rude, heavy boulders did the duty then,

And each one had its title, as `The Horse'

One was 'The Cockit-hat' and one `The Hen'

`The Kirk,' `The Saddle,' President' and `Soo,'

`The Bannock,' 'Baron,' `Fluke,' and `Robbie Dow.' "

BRECHIN.—At Brechin Castle are old stones, found

in making present pond thirty years ago. They are river boulders in natural

shape, with a piece of iron inserted for handle.

CAMBUSNETHEN.—Specimens of rough stones with

wooden handles and one sole, in use from 1789 to beginning of present

century. CHIRNSIDE.-Six

pairs of very old stones are in possession of T. A. Calder, a. member of

this club. They were found in and in the bottom of Bonkyll Curling Pond

about forty years ago. They are hard unpolished whinstones with iron

handles. CLUNIE.—Several

of various shapes and weights: blocks of unhewn stone, with smith-made iron

handles. One is oval, measuring 46 inches in circumference, and weighing 9

lbs.; another, 90½ lbs.

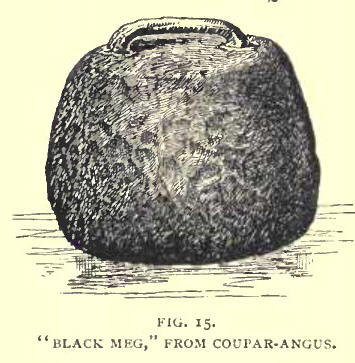

COUPER

ANGUS.—The following are the names and weights of a few of the more

celebrated stones in the possession of the club: — "Suwaroff," 84 lbs. COUPER

ANGUS.—The following are the names and weights of a few of the more

celebrated stones in the possession of the club: — "Suwaroff," 84 lbs.

"Cog," 80 lbs.; "Fluke," 72 lbs.; "Black Meg," 66 lbs.; "The Sant. Packet,"

116 lbs.

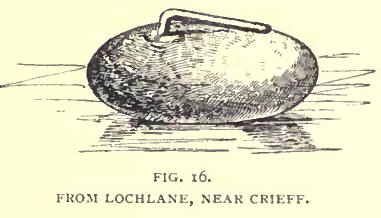

CRIEFF.---Several stones were found in 1881 at Lochlane, on Lord

Abercrombie's estate of Ferntower, near Crieff, and all or several of which

fell into the possession of Mr James Gray, builder, Bridge of Allan.

One

of these (Fig. 16) was given to Mr Henderson, Linlithgow, and presented by

him to the Royal Caledonian Club. The stones were found under the lower

steps of a spiral stair, the cavity having been built up with masonry. to be

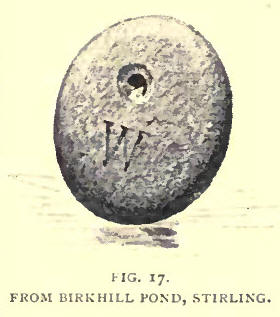

seen in the Antiquarian incised in it. It was found in Brinkhill Pond,

Stirling, and belonged to the late Dr Mushet. One

of these (Fig. 16) was given to Mr Henderson, Linlithgow, and presented by

him to the Royal Caledonian Club. The stones were found under the lower

steps of a spiral stair, the cavity having been built up with masonry. to be

seen in the Antiquarian incised in it. It was found in Brinkhill Pond,

Stirling, and belonged to the late Dr Mushet.

DALTON,

ST BRIDGETS.—An oblong oval stone is in possession of Robert Underwood,

Hightae. It is supposed to have been formerly in use on the southernmost of

the "mony lochs" of "Marjorie" (Lochmaben). DALTON,

ST BRIDGETS.—An oblong oval stone is in possession of Robert Underwood,

Hightae. It is supposed to have been formerly in use on the southernmost of

the "mony lochs" of "Marjorie" (Lochmaben).

DELVINE.—(see above under Blairgowrie).

DOUNE.—A stone, with the inscription I. Mc,

1732, is possessed by the club. It weighs about 5 0 lbs. This stone was

found some years ago when re-causewaying the close that leads to what is

known as The Clans' HaIl—a famous hostelry and favourite resort of curlers

in the latter half of last century. It is 102 inches long, and 91 inches

across at the broad end, and its contour is altogether quite unique, even

among stones of the boulder type. Another stone of similar shape, but

larger, used to be seen on the table at the annual feasts of the club, when

the late James Macfarlane, Woodside Cottage, was president. It belonged to

Archibald Greig, a noted and powerful curler of last century. This stone, we

believe, is now the property of William Forrester, at Campsie.

DUNBLANE.—There are two ancient stones here,

"The Provost," and "The Bailie," weighing about 60 lbs. each.

DUNFERMLINE.—A stone with DM:1696 carved on it.

It weighs 66 lbs., and resembles the half of an egg cut long ways. It has an

iron handle, run in with lead, is 38 inches in circumference Lengthways, and

30 inches measuring over top and round sole.

DUNS.—An animal expedition used to be made in

olden times to the Pease Burn, near Cockburnspath, to procure boulders, into

which rough iron handles were fastened. This custom existed till the

publication of the Rules of the Dudingston Society, when round stones came

gradually into use. The pride of this club, in the way of old specimens,

used to be "Rob Roy," a large whinstone, block, 18 inches in diameter, and

54 inches in circumference, without chisel or hammer mark. "Rob" was

purchased, in 1826, by David M`Watt, from a mason in Polwarth, for the sum

of 10s. 6d.; but he has been missing since 1856. "The Guse" and "Bluebeard"

have also gone astray; but "The Egg" is to the fore in the safe keeping of

Charles Watson.

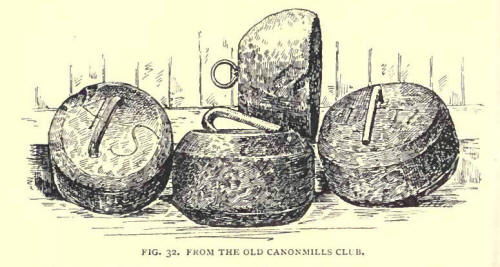

EDINBURGH.—That the game of curling was in ancient times practised in and

around Edinburgh there is no doubt. We have already noticed the stone of the

early type to be seen in the Antiquarian Museum, and later on we refer to

stones that point back to the days of the old Canonmills Club. A specimen of

the second type of stone—the rough boulder—is illustrated in the Annals of

1841-42; and the following notice by Mr Palmer of Currie would seem to

suggest that curling was practised in other parts of the town besides the

Nor' Loch and Canonmills

"In digging a drain to the east of Watson's

Institution,' [Situated about half-way between Dean Bridge and Coatbridge.]

near Edinburgh, a layer of mud and refuse, to the depth of 3 feet, such as

are usually deposited in the bottom of old ponds, was found. A regularly

laid causeway, 8 or 10 yards in width and about 20 in length, spewed, from

the slight embankments at the sides of the causeway, that it was evidently

laid down as a bottom for a pond.

"In removing the mud, there were discovered

about half-a-dozen roughly made curling stones, which were allowed to lie

about the field for about a fortnight, during which time they were all

broken to pieces (apparently for the sake of the old iron of the handles—proh

pudor) save one, a fair sample of the rest, which luckily escaped the Gothic

destruction, and yet remains to tell the tale.

"It is a semi-spheroidal block of coarse-grained

whinstone, weighing 65 pounds. The sole is 11 inches in diameter, and

hollowed out a little in the middle, so that it runs upon a ring about 2

inches wide. The stone is about 6 inches high, and has an iron handle of the

common kind fixed in the usual place.

"There is no person in the neighbourhood (and

there are some who have laboured in the fields about for more than half a

century) who has any recollection of the place being anything else than an

`old pond' and not one who ever heard, even by tradition, that curlers had

erst practised their manly game upon it and of course they were not a little

surprised when the hand of modern improvement revealed the secrets of old

Father Time. "From this

circumstance, and the depth of the deposit over the causeway, it is evident

that the pond must have been made `langsyne,' but the precise date must be

matter of mere conjecture."

What has become of this old stone, and was this

submerged pond an earlier specimen of an artificial curling-pond than either

Cairnie's or Sommerville's?

FOREST.—Two stones of early ; date are in

possession of W. Richardson, St Mary's Cottage. One (whin) flat on both

sides—the other of coarse granite, flat below but round above, thus

with hole

in centre for handle. with hole

in centre for handle.

GARGUNOCK.—Here are some old stones "like a tailor's goose."

GLADSMUIR.—An old curling-stone is to be seen at

the door of a house which was formerly the old coaching-inn, and its handle

does ditty in scraping the mud off the boots of the inmates and their

visitors. HADDINGTON.-Regarding

a find of old stones here, Canon Wannop writes:-

"Dr Howden (father of the present venerable

practitioner of that name) told me soon after I came to Haddington,

thirty-four years ago, that when he was a boy some alterations were being

made on the Bowling-green (which is said to be the oldest in Scotland), when

some old curling-stones, in the form of unpolished boulders with iron

handles battened into them, were dug up. Nobody at the time knew what they

were or for what they had been used. The Bowling-green was close to the

River Tyne; and the inference is that the game had formerly been played

there, but had been given up for some time in the end of last century."

HAWICK.—There is here an old curling-stone

called "The Whaup," the handle being like a whaup's bill. Another is called

"The Town-Clerk."

JEDBURGH.—One old stone is called "The Girdle," another "The Grey Hen,"—the

property of A. Smith, Paradise.

LOCHMABEN, according to Sir Richard Broun in

1830, had them several relics of the olden times—and of the introduction of

the game, "Which are

looked upon with a sort of filial veneration as being monuments of the

fathers of those far-back times, whose names are associated with the art,

and whose fame in the past still sheds, as it were, upon the present a

reflected gleam. . . . The greater part, however, were borrowed in the end

of last century by Herries of Hall-dyke, and could never find their way back

from the banks of the Milk. Amongst these remaining, the most remarkable is

the famous 'Hen,' which still exists in all the pristine elegance and

simplicity of form, as discovered by old Thornywhat and the late Provost

Henderson in a cleugh upon the estate of the former, and conveyed down to

the Burgh in a plaid. She was used, says our informant, in all our parish

spiels, till, taking her to Dumfries, where stones of an improved make were

earlier introduced than with us, we were ashamed of her ; for, when once

near the tee there was no removing of her. Wherever she settled, there she

clocked ; and the severest blow merely destroyed her equilibriurn, turning

up her bottom to the light."

The "Sutor" was the name of another Lochmaben

stone. Then there were "Skelbyland," "The Craig," "Wallace", "Steelcap,"

"The Scoon," "Buonoparte," "Hughie," "Redcap," and "The Skipper," all noted

and associated with the names and feats of other days. Doubtless the

Lochmabenites whose prowess Sir Richard immortalised, and who are still

ready to souter their opponents on the ice, will continue to hold these old

heroes in reverence.

MUTHILL.—One stone in possession of this club is a square block named "'The

Bible " (Fig. 18); another, oval shaped, "The Goose" (Fig. 19); another,

"The Hen." One since lost was said to be the weight of "a boll of meal."

MARKINCH.—Old stone (in possession of the

Matron, John Balfour of Balbirnie) which has for more than a century borne

the name of "The Doctor," of the same shape as an old triangular smoothing

iron, with a well-fastened old iron handle. The stone is about 60 lbs.

weight. NEWTYLE.—One

old specimen is still preserved—a natural quartz boulder of unshapely build,

with an iron handle inserted, and weighing about 70 lbs. Smaller boulders

with three finger holes were once on the pond, entitled "The Goose" and "The

Gander," but they have both flown away. Other old stones were known as "The

Prince" and "The Kebbuck."

PITFOUR.—Within the last few years stones have

been found in this district doing duty in keeping tIle thatch on the roofs

of houses and hay-ricks, and supposed to be at least 150 years old. They are

rough and round or oval in shape, weighing from 20 to 30 lbs., with a piece

of rusty iron sunk into the top for a handle. They are evidently water-worn

and picked up from the sea-shore, or the bed of the nearest river. Colonel

Ferguson of Pitfour has two pairs of such stones.

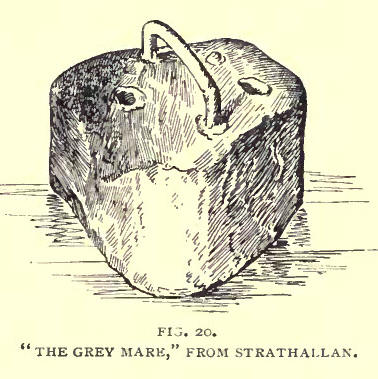

STRATHALLAN

MEATH MOSS.—Several old stones with iron handles, very rough, and with no

trace of work on them. One very old (Fig. 2 0) called "The Grey Mare," used

to be set on the table at curling dinners. The stone is just as it would be

when taken from the channel of the river. It has a handle inserted in it,

but from the holes that are also found pierced on its upper side it is

supposed by its owners to have been played once upon a time without a

handle. If this be so (but the size of the stone makes us doubtful) it is

interesting as shewing the transformation from the first to the second type

of stone. [Since this notice was in type we have received information from

the secretary of this club (R. Maxtone) of the discovery of a stone of the

earliest type by James Brydie, Hillhead, on the site of an old curling pond.

The stone weighs 23 lbs., and is an admirable specimen of the "loofie

channel-stane."] STRATHALLAN

MEATH MOSS.—Several old stones with iron handles, very rough, and with no

trace of work on them. One very old (Fig. 2 0) called "The Grey Mare," used

to be set on the table at curling dinners. The stone is just as it would be

when taken from the channel of the river. It has a handle inserted in it,

but from the holes that are also found pierced on its upper side it is

supposed by its owners to have been played once upon a time without a

handle. If this be so (but the size of the stone makes us doubtful) it is

interesting as shewing the transformation from the first to the second type

of stone. [Since this notice was in type we have received information from

the secretary of this club (R. Maxtone) of the discovery of a stone of the

earliest type by James Brydie, Hillhead, on the site of an old curling pond.

The stone weighs 23 lbs., and is an admirable specimen of the "loofie

channel-stane."]

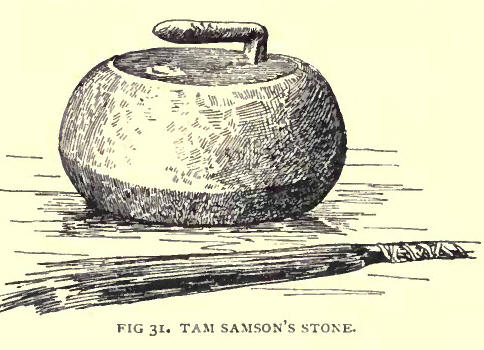

TWEEDSMUIR.—One ancient specimen, shaped somewhat like a Tam o' Shanter

bonnet, is in possession of a member of this club. It was found in the

bottom of a deep pool in the Tweed, near Crook Inn.

TYNRON.—The curling-stone which belonged to John

M'Call, farmer, Glenmanna, Penpont, can be seen in Dr Grierson's Museum,

Thornhill (parish of Morton), where there is a. famous collection of

antiquities. It is a ponderous block weighing some 75 lbs. This John M'Call

was a very powerful man. Many stories are told of great feats of strength

performed by him. He "flourished" about 100 years ago.

[From the following Clubs we have also been

favoured with notices regarding old stones either in their possession, or in

the neighbourhood. They do not all refer us back to the time under

consideration, but they supply information that certainly links the present

with the past in an interesting way. The clubs are given in alphabetical

order :—Achalader (Airth, Bruce Castle, and Dunmore), (Antrum, Alevater and

Mounteviot), Ballingry, Balmerino, Belfast, Breadalbane (2 clubs), Bridge of

Allan, Cardross and Kepp, Castlecary Castle, Ceres, Croy, Cupar-Fife,

Dirleton, Doune, Dumfries, Dunglas and Cockburnspath, Eaglesham, Earlston,

Forrestfield, Fort-Augustus, (reenlaw, Hamilton, Hercules, Inverness,

Kinnochtry, Kinross, Kirknewton, Lees and Lithtillunm, Lillieslcaf,

Lochwinnoch, Logiealmond, Manchester Bellevue, _Meg,'inch, Melville, Methven,

Minnigaff, Montreal, Newport, Orwell, Penning'flamc, Pitlessic, Reston,

Roslin, Scotscraig, Shettleston, Spean, Stoneycreek, Stow, Strathkinnes,

Tinwald, Trinity Gask, Woodside (North), Upper Kithsdale.]

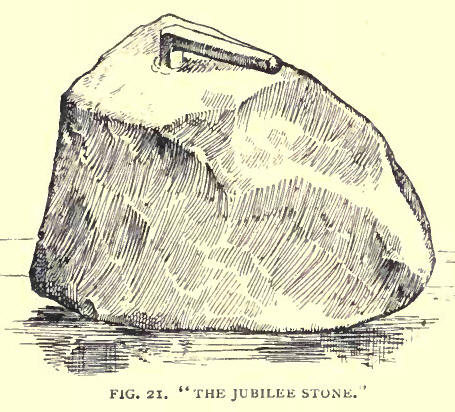

We

have kept to the end of the list "the king o' a' the core,"—the "last but

not the least:" the greatest in fact, of all that mighty race. In the

circumstances in which he has made his appearance he claims a special title

underneath his portrait, and we have therefore called him "The Jubilee

Stone." This extraordinary stone that now beats the record formerly field by

"The Saut Backet " of Coupar-Angus, was presented to the Popil. Caledonian

Club by John Wilson, Chapel-lull, Cockburnspath, and exhibited on its

arrival, at the Jubilee meeting of the club, held on the 25th July 1888; and

its portly presence also graced the banquet on November 28th. It weighs 117

lbs., and belonged to John Hood, a keen curler of that district, who died at

Townhead in January 1888. Mr Hood, it appears, had often seen his father

play the stone, and lie himself had played it occasionally before dressed

stones were introduced. It was sent by Mr Wilson to be preserved in the

archives of the Royal Club ; and we are sure that future generations of

curlers will look upon it with interest and astonishment, if not with

dismay. We

have kept to the end of the list "the king o' a' the core,"—the "last but

not the least:" the greatest in fact, of all that mighty race. In the

circumstances in which he has made his appearance he claims a special title

underneath his portrait, and we have therefore called him "The Jubilee

Stone." This extraordinary stone that now beats the record formerly field by

"The Saut Backet " of Coupar-Angus, was presented to the Popil. Caledonian

Club by John Wilson, Chapel-lull, Cockburnspath, and exhibited on its

arrival, at the Jubilee meeting of the club, held on the 25th July 1888; and

its portly presence also graced the banquet on November 28th. It weighs 117

lbs., and belonged to John Hood, a keen curler of that district, who died at

Townhead in January 1888. Mr Hood, it appears, had often seen his father

play the stone, and lie himself had played it occasionally before dressed

stones were introduced. It was sent by Mr Wilson to be preserved in the

archives of the Royal Club ; and we are sure that future generations of

curlers will look upon it with interest and astonishment, if not with

dismay. Such, then, are

the memorial stones of the giant age of curling. Varied is their destiny

from the ignominious lot of the poor outcast that acts as a foot-scraper in

the parish of the first historian of the game, to that of "the doctor,"

snugly ensconced in the patron's private parlour at Markinch, or, higher

than all, of the great monarch who presides at our banquets, and then sits

in state at the secretary's office to receive the admiring homage of his

subjects, who hail from every frosty clinic to pay respect to His Majesty.

They are indeed a "core" of matchless weight and power. In measuring against

them our modern capabilities, we ought, no doubt, to bear in mind that the

rink in those days was in all likelihood much shorter than it is now and

each pIayer used only one stone—the number of players on each side being

usually eight; but, even with such differences taken into account, we must

own that these big blocks alarm us with the conviction that the dissipation

of energy is going on more rapidly than natural philosophers seem to think.

Few of us would care to have

our life depending on the chance of sending the Jubilee stone "owvre a'

ice." 'Tak in by the handle" would be the cry that sealed our doom; but the

Titan of Cockburnspath thought nothing of the burden as he enjoyed the play;

and, if these weighty stones could speak, they would doubtless relate how

sweetly they were swung by the arms of their owners, and how gently they

were carried to and from the loch—very often in the cosy corner of the

shepherd's plaid. We have no reason to suppose that Cairnie's heroes,

William Gourlay and Aleck Cook were mythical—though we "sing small" as

William plays his 72-pounder, which takes off the guard full, moves on, and

in its progress raises half-a-dozen stones in succession, and gains the shot

that was declared to be impregnable. They cannot do that nor can we rival

Aleck the "ambidexter," who swung his long arm "so high, with the

curling-stone behind him, that, when about to raise the double guards, a

person standing on the tee opposite could see its entire bottom:" We listen

and believe (?) all that Broun tells us about the irate CIapperton, who

"seized the Lochmaben 'lien' with an arm of triumph, and whirled her

repeatedly round his head, with as much ease, apparently, as if she had been

nearer seven than seventy pounds; and when he relates how the president, in

reply to Laurie Young, the strongest player in Tinwald, who had challenged

the Lochmaben party to a trial of arm, stepped out, took his stone and threw

it with such strength across the breadth of the Mill Loch (nearly a mile),

that it stotted off the brink upon the other side, and tumbled over upon the

grass, adding thereafter—"Now, sir, go and throw it back again, and we'll

then confess that you are too many for us."

"There were giants in those days." We had better

just allow at once that the former days of curling "were better than these,"

in the physical force line. Herein just lies the difference between the

ancient and the modern game. As we engage in it now, we do so that we may

improve our physical as well as our mental and spiritual condition; but,

with the beautiful implements now in our hands, we have something else to do

than to shake a display of force. In curling, as in other accomplishments-

"It is well to have a giant's strength,

But tyrannous to use it like a giant."

To "draw," and "wick," and "creep through the

port," and "curl round the guard to the winner;" to "elbow in," and "elbow

out," and, in a hundred other ways, to temper force with discretion and

"canniness"—to reduce stone-throwing to one of the fine arts—this is the

modern curler's ambition, and, in as far as he succeeds, he advances beyond

the possibilities of ancient curling. It can easily be understood that, with

these coarse three-neukit stones, the niceties of the modern game were out

of the question: they played—they had to play, a striking game, and

stone-breaking was heroic at a time when stones cost nothing, but had simply

to be lifted of the nearest dyke or out of the nearest burn. It is not

surprising, therefore; to find that thunder is predominant in any

descriptions we have of the middle age of curling. One or two of these are

found heading this chapter. Mr Muir's picture recalls a style of play that

must have been on the wane when he sung his spirited song to the Duddingston

Club:- "A stalwart chiel,

to redd the ice,

Drives roaring down like thunder

Wi' awfu' crash the double guards

At ance are burst asunder

Rip-raping on frae random wicks,

The winner gets a yether;

Then round the tee we flock wi glee

In cauld, cauld, frosty weather."

As a Yankee would say, "I guess they found some

road metal beside that tee."

When Davidson (1789) describes the great contest

which took place at Carlingwark, between Ben o' Tudor and Glenbuck (Gordon

of Kenmure) in the olden time we "hear afar" the noise of rattling shots and

reckless shooters:- The

stares wi' muckle martial din,

Rebounding frae ilk shore:

Now thick, thick, thick, each other chased

An' up the rink did roar.

They closed fast on every side,

A port could scarce be found

An' many a broken channel-stane

Lay scattered up an' down.

Shew me the winner, cried Glenbuck,

An' a' behind stan' off:

Then rattled up the roaring crag

An ran the port wi' life."

Rough as the ancient game might be, it was,

however, on such a granite foundation that the sociality and brotherhood of

curling meetings were built up. The pillars of the bonspeil, "rivalry and

good fellowship," were then laid strong and deep—never to e shaken.

Thus did Bentudor and Glenbuck

Their culling contest end;

They met baith merry i' the morn,

At night they parted friends."

And thus did other contests begin and end. Then,

as now, the motto was, "meet friends and part friends;" and in their hard

fighting our forefathers did no forget what we try to remember, that, on the

icy plain, courtesy is due as much to those who vanquish us as to those who

are vanquished by us.

"In those days," says Mr Wilson in sending the Jubilee stone, and referring

to the time when such toys were used by his own and John Hood's ancestors,

"the gude-wife of the farmer used herself to carry to the pond luncheon in

the shape of a 'bicker of prose' made with the 'broo' of the beef and greens

being prepared for dinner, and all the players sat around and partook of

this substantial fare, washed down, we may safely assume, by a little of the

national beverage. After play was over they adjourned to discuss the said

beef and greens, and to 'fight their battles o'er again' over unlimited

tumblers of toddy." We have not, with all our advancement, beaten that

record of simple, homely, social enjoyment; the curling of the future never

will, for in such fellowship we "gie the grip " to a' keen curlers. The

manner of play—be it of the loofie days or the big boulder age, or of

some unimagined period which shall yet cast our own, with its boasted

perfection, into the shade, matters not: we are brithers a.', and the good

fellowship that binds its together in every age is stronger than the

developments that distinguish one age from another in the history of "our

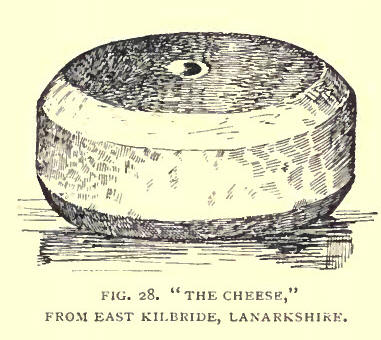

ain game." THIRD TYPE:

THE CIRCULAR STONE.—The acquisition of a "handle" by the typical mortal to

whom reference has been made, with the consequent power and influence, does

not at first bring polish and refinement: the angles or corners have still

to be rubbed off; and this is the next stage of development entrusted to the

forces of civilisation, culture, and society. The evolution of the

curling-stone proceeds on similar lines. The squaring of the circle is

proverbially impossible, and the problem, happily, was not set before the

curler. His task was to make circular what was found square, oval, three-neukit,

hexagonal, or indescribable, as the case alight be; and it is evident, from

our illustrations, that he had every form and shape to work upon. Who first

accomplished this? For, was not the inventor of the circular stone the true

originator of curling? Did he not draw the game away, as we have said, from

its former modes and conditions so completely as to leave no connection,

except what can be recognised by the faculty that deals with the evidence of

what is not seen? The game of curling, in its origin, and in the incidents

of its progress, seems to be the work of some power other than human: it

comes as a gift from the unseen—keen curlers call it a divine gift; and, no

doubt, it is such if they use it aright, for it is the use of them that

makes all gifts divine or the opposite. The inventor of the circular

curling-stone, like the inventor of curling, is, and must remain, a "great

unknown." In our historical survey of the subject we content ourselves by

saying that the development was natural, and we wonder with those who wonder

that it did not come about sooner. We make a polite bow of thanks in name of

our countrymen to those writers (generally countrymen themselves) who argue

that the late appearance of the circular stone is an argument for the recent

origin of the game, on the ground that our intelligence would not have

allowed it to remain so long so imperfect.

["Had the game been of very ancient origin, we

should expect many of these improvements to have been made long before the

time when they actually were made. As society advances in improvement, arts

- and sciences advance at the same time. No human thing remains stationary.

If, then, we find curling-stones, at any period, in the rudest possible

form, having received no improvements, we have reason to conclude that the

origin of the game cannot be far distant from that period."—Duddingston

Account, etc., p. 17.

"That the game cannot boast of hoary antiquity is a conclusion which may

also be arrived at by a process of reasoning which dispenses with written

records, viz., from the rude shape and finish of curling-stones and handles

until within a very recent period. It is alleged that, in some instances,

within the memory of men still living, the stonesured merely a niche for the

finger and thumb to serve as a handle, and they were really `channel-stanes

' taken front the river or brook. The improvements in handles and stones

went on simultaneously at a rate, until a near approach to mathematical

precision was attained. Had curling been known in the Middle Ages these

improvements would doubtless have been effected sooner, for our noble

ecclesiastical piles and feudal strongholds bear ample testimony to the fact

that stone-masons, who usually mould and fashion curling-stones, were no

less accomplished tradesmen in mediaeval times than they are now. It may be

argued, however, that the blocks of which curling-stones are made are more

difficult to mould than stones hewn for cathedrals and fortresses. While

this is readily admitted, it is equally true that not one of the

curling-stones, even of so recent a date as the last century, possesses the

polish or finish usually met with in the ancient querns, or hand

mill-stones, which for many centuries were in universal use for grinding

corn, and which were often moulded out of solid whinstone."—J. B.

Greenshields, Annals of .Lesmaha flow (1864), p. 20.5.]

But the argument won't do. Old channel-stales,

like facts, "winna ding, and downa be disputed," and we have now got

evidence that they were in existence more than two centuries before the

rounding of the stone brought in the new era of curling, and the

intelligence of our countrymen was applied to the improvement of the stones.

The proof of antiquity assails the pride of intelligence. The compliment is

changed into a reflection, containing a rebuke. The bright palladium marked

"1511," which, as we have seen, guards us against a. foreign origin, within

a glass case at Stirling, becomes a bitter pill which (pace the Curator of

the Smith Institute) must be swallowed nolens volens; and we have simply to

confess that the lateness of the circular stone is a great discredit to

Scotland, and is unaccountable, except, perhaps, on the ground that our

forefathers found so much enjoyment in the imperfect game as to keep them

from thinking of improving upon it. Dr Samuel Johnson held that Scotland

consisted of two things—stone and water; and, as these are the primal

elements in the ancient game, he doubtless referred to this deficiency when

he remarked that, with all our learning and advantages, we were devoid of

elegance and embellishments till the Union! [He (Dr Johnson) owned the Scots

had been "a very learned nation for one hundred years—from 1550 to 1650, but

they afforded the only instance of a people among whom the arts of civil

life did not advance in proportion with learning: that they had hardly any

trade, any money, or any elegance before the Union: that it was strange

that, with all the advantages possessed by other nations, they had not any

of those conveniences and embellishments which are the fruit of industry,

till they came ill contact with a civilised people."—Boswell.] It is

interesting to notice that the visit of the grand old grumbler who did so

much to take the conceit out of us, was made about the time that curling set

out on its career of elegance and embellishment; and it would, perhaps, be

more correct to ascribe the improvement in curling to Dr Johnson's Tour to

the Hebrides in 1773, than to the Union. It is certain, indeed, that neither

had anything to do with the matter; and, as far as we can judge, the time of

the improvement is neither an argument for the recent origin of the game,

nor a reflection on the want of intelligence in those who played away so

long with loofie-stones, and sea, stream, or dyke boulders. Greater latent

possibilities than the circular channel-stane have lain for ages

undiscovered and undeveloped, and very often accident, or what is so-called,

only brought them to light. Then everybody wondered that they had never been

discovered or invented before—they were so simple. The greatest genius is he

who can write something, or invent something, so true to nature that

everybody admires its simplicity, and feels that it ought to have been done

long; ago, and that everybody might have done it.

Among the motley throng of boulders that

gathered within the brough as the ancient game went on, there were to

be found now and then stones worn quite circular, as we may find them yet by

the action of stream or sea—nature's productions. The players could not fail

to see a fitness about these that the others did not possess for dealing

with certain situations occurring in the struggle to lie nearest to the tee,

and out of this, doubtless, arose the idea of making all stones circular.

An outsider may have followed us till now

without being led to inquire as to the manner of playing the game and the

aim of the players, and we may take him so far into confidence at this stage

as to furnish him with the earliest description of the game—that of Pennant,

who made a tour in Scotland in 1772: - [A Tour in Scotland and Voyage to the

Hebrides, 1772. 2nd edition. Part I. page 93.]

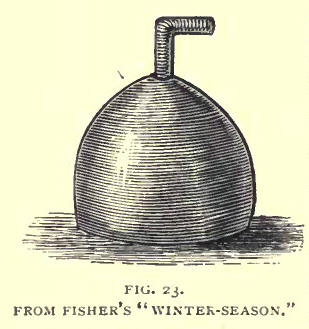

"Of the sports of these parts," says Pennant,

"that of Curling is a favorite; and one unknown in England: it is an

amusement of the winter, and played on the ice, by sliding from one mark to

another great stones of forty to seventy pounds weight, of hemispherical

form, with an iron or wooden Handle at top. The object of the player is to

lay his stone as near to the mark as possible, to guard that of his partner,

which had been well laid before, or to strike off that of his antagonist."

There is little to add to this concise

description, except to say that in these times the rink or distance from

mark to mark (tee to tee), was generally no more than 30 yards; that the

player steadied himself in delivering his stone, and kept his footing on the

ice by means of cran pits (grippers, crisps), in appearance like

stirrup-irons, and fixed on his shoes .like skates, having prongs underneath

to grip the ice. In a contest there were then generally eight players on a

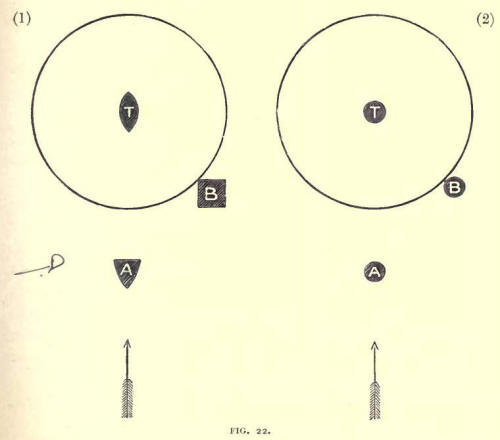

side, each playing one stone. With this preface we may introduce a plain

diagram (Fig. 22) to show the difficulty of skilful play with the ancient

stones, and the possibilities developed by the circular ones. It is not

certain that in these times the players were particular in playing over one

tee to the other, but, with their crampits on their shoes, they

would move off and make a flank attack when the enemy's front lines were

impregnable. This was, however, even in these times, bad form, and we may

suppose the player's stone to be coming in the direction of the arrow.

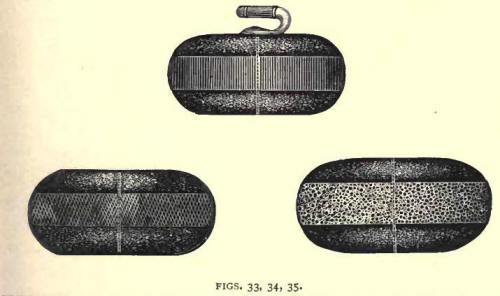

One circle or brough is drawn, of 8 feet in

diameter (the diameter in the early days ranged from 2 to 12 feet). In (1)

we have an oval stone, T, on the tee, guarded by an angular stone, A. These

are both the enemy's; and the player, with a three-neukit stone, is about to

play, his object being to remove the oval stone of the enemy from its

position on the tee. Touching the circle on the right of the triangular

stone or guard is the square stone B on his own side. What is he to do? How

will his three-neukit stone find the winner? The shot is no doubt a possible

one; it may even be demonstrated as such by mathematical science, or taken

in at a glance by a warlock like the renowned Tam Pate, who, with a three-neukit

stone, never missed a shot in the famous match of the Duke of Hamilton

against M`Dowall of Garthland in 1784. We venture to say, however, that in

an ordinary case the player would simply send up his stone and let it take

its chance, not knowing what it

might do. In (2), with the same object in view,

the stones in their corresponding positions being circular, and the stone

which the player is about to play being also circular, it is at once evident

that he can find the winner on the tee, and displace it in several ways. The

proverbial three courses, at least, are open—to curl past the guard with the

Fenwick twist (of which more under "The Art of Curling"), and change places

quietly with the winner; to cannon or wick on the inner side of B, and at an

angle do the same thing; or to wick B on the outer side, and force it to

displace the winning-stone, and rest itself on the tee, which wouId be

equally successful, since B is on the player's side. In the position of this

game it will be noticed that only three have played out of the sixteen which

were generally found in conflict—eight against eight, in ancient times ; but

as the number of stones within the circle increases in (1), the difficulty

of skilful play will increase, and force and chance will more and more rule

the destinies of the fighters while in (2), though force will at times be

needed to clear complications, and chance continue to give its spice of

interest to the game, the player of skill will more and more be required for

the kittle shot, and the last of all will most likely require to be the most

skilful. Now there may

be a dubious precision in the situation of affairs thus sketched, for it is

not likely that the variegated implements would ever fall into position

exactly as above described; but it is enough if we have illustrated the

nature of the change brought about in curling by the circular shape of the