|

"What numbers can describe

The various game? .

Or couldst thou follow the experiene'd play'r

Through all the myst'ries of his art? or teach

The undiciplin'd how to wick, to guard,

Or ride full out the stone that blocks the pass?"—GRAEME

AN

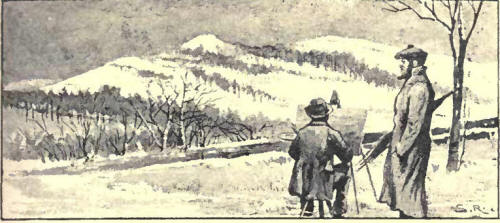

ye no curl, man?" said a brawny Dumfriesian herd to an artist whom he found

sitting on the hill-side, trying to transfer to canvas the sparking

snow-clad scene. It was a fine clear curling morning, and that shepherd

could not for the life of him understand how a sane, able-bodied person

could employ himself in such a contemptible way when the ice was bearing on

the loch in the valley below, and the curlers, with their brooms over their

shoulders, were gathering from all directions to join in the manly sport. He

glanced at the "bit picter," then carefully surveyed the artist from head to

foot, and seeing no physical defect to account for such strange conduct, the

shepherd, with a look of pity and scorn, blurted out his blunt question, and

wended onward to the bonspiel, muttering something about the "puir, feckless

body, that couldna belang hereaboots." The painter, in return, pitied the

curling keeper of sheep, and worked his honest country-man and his

brother-curlers as "objects" into the landscape. The curler and the artist

did not see eye to eye. Anybody could paint, thought the one and a sensible

man would not waste his time in such a silly way on a fine frosty morning.

Any rustic could cull, thought the painter. There was certainly no art in

the game; and as for any enjoyment in it, his idea was like that of the

Oriental who, on being informed that many of the players in a cricket match

which he had been looking at were rich men, expressed his surprise that they

did not employ some poor people to do it for them. A person who does not

know anything about a game generally sees little in it. In the case of

curling the uninitiated onlooker sees even less than AN

ye no curl, man?" said a brawny Dumfriesian herd to an artist whom he found

sitting on the hill-side, trying to transfer to canvas the sparking

snow-clad scene. It was a fine clear curling morning, and that shepherd

could not for the life of him understand how a sane, able-bodied person

could employ himself in such a contemptible way when the ice was bearing on

the loch in the valley below, and the curlers, with their brooms over their

shoulders, were gathering from all directions to join in the manly sport. He

glanced at the "bit picter," then carefully surveyed the artist from head to

foot, and seeing no physical defect to account for such strange conduct, the

shepherd, with a look of pity and scorn, blurted out his blunt question, and

wended onward to the bonspiel, muttering something about the "puir, feckless

body, that couldna belang hereaboots." The painter, in return, pitied the

curling keeper of sheep, and worked his honest country-man and his

brother-curlers as "objects" into the landscape. The curler and the artist

did not see eye to eye. Anybody could paint, thought the one and a sensible

man would not waste his time in such a silly way on a fine frosty morning.

Any rustic could cull, thought the painter. There was certainly no art in

the game; and as for any enjoyment in it, his idea was like that of the

Oriental who, on being informed that many of the players in a cricket match

which he had been looking at were rich men, expressed his surprise that they

did not employ some poor people to do it for them. A person who does not

know anything about a game generally sees little in it. In the case of

curling the uninitiated onlooker sees even less than

usual, and what he does see

appears absurd. A Canadian farmer at Quebec, after witnessing the game for

the first time, gave this description of it:-

"J'ai vu aujourd'hui une

bande d'Ecossais qui jetaieiit des grandes boules de fer, faites coninie des

bombes, sur la glace, a.pres quoi ils criaient soupe, soupe ; ensuite ils

riaient coninie des fous; je crois Dien qu'ils sont vraiement foes."

An Englishman, who is now a

keen curler, tells us that when he first saw a game of curling, one of the

players—a very lean, hungry-looking individual—was gesticulating wildly, and

yelling at the pitch of his voice, "Soop! ye deevils; soopI" the Englishman

thought the poor fellow was starving, and crying out in despair for some

"soup" to put warmth into his benumbed frame. In a match between the

Bradford and the Blackburn clubs, several doctors happened to be in the

rinks. One native, who, in his own opinion, knew all about it, was overheard

informing another, who did not disguise his ignorance, that the players were

lunatics from a neighbouring asylum going through their exercises, and that

what they were now and then drinking was medicine to keep them right. The

curler's equipments do not help the outsider to understand the hidden art.

When the members of the Darlington club first appeared in the streets of the

town flourishing their besoms, some municipal changes had just taken place,

and the people took the curlers to be a special force of scavengers sent

forth to perform the proverbial clean sweep. In the winter of 1876-77, the

pond of the Wigan and Haigh

club having been rendered

useless by a heavy snowstorm, the members sallied forth to play on Martin

here, a large tract of water lying between Wigan and Southport. The day was

densely foggy, with intense frost ; and as the curlers had all long beards,

their Father Christmas appearance and the queer weapons they carried

frightened the villagers of Martin so much that the landlord of the inn

actually refused to supply them with refreshments. [The stationmaster, who

had a better idea of then,, took pity on the curlers, and presented them

with a small barrel of beer. But this (lid not end their day's troubles. The

barrel was conveyed in a cart to the field of battle, placed in position,

duly tapped, and left ready for use. In the keen play the barrel was left

unnoticed for three hours, but at last "the weary drouth cam' up their

throats." A truce was called, and with one accord they invoked the favour of

the kindly barrel. Judge of their horror when the curlers found that beer

and barrel were frozen into a solid lump ! They left for home.]

Now, whatever aspect the game

of curling may assume in the eyes of the uninitiated, there is really no

game which, to be played with any degree of perfection, requires so much

skilful resource on the part of the player. Precision of eye, clearness of

head, steadiness of aim, accuracy of judgment, dexterity of hazed, force

tempered by discretion, decision of character, coolness, confidence, and

enthusiasm are all necessary. No two "ends" are exactly alike. There is

infinite variety in the game:

"New efforts, new schemes

every movement demands."

In a moment the whole

situation of affairs may be changed, and the best-laid schemes of the skip

be sent agley. New tactics must then be adopted, and fresh resources must

ever be available to overcome new difficulties and cope with new

emergencies.

"I doubt," says an excellent

authority, [Thomas Brown, the "Maida" of Bell's Life and other papers.] "if

any one who has participated in a curling bonspiel between two neighbouring

parishes, where skill and enthusiasm were nearly matched, could be found to

admit that there is anything in sport that can compare with the earnest

enthusiasm, the skilful manipulation, the combination of strength and

science, with just sufficient of chance to lend a charm to the uncertainty

that is experienced in a well-fought bathe of curling."

It is in the bonspiel, that

the true art of curling is exemplified. The renown which certain curling

clubs have gained for excellence in the art is based on the matches they

have gained against other clubs. The heroes whose names are remembered with

honour in their different districts won their spurs in the bonspiel.

Point play is not the most

difficult part of the curling art. The art must always be held to include a

great deal more than "points." The low average scoring its the point game to

which we have referred may, however, shew how difficult it is to attain to

anything like perfection in curling. Perhaps it is as well that perfection

is unattainable. Tam Pate appears to have been the only perfect curler that

ever lived, and they dubbed hire warlock. We must be content with a

qualified measure of proficiency. To be human, we must err. If a curler

never missed a single shot, he might get an ill name and be hanged. On the

other hand, a right-minded curler would rather be hanged than be a dffjer;

he would rather be "awa' to the "caff-neuk" than be a senseless "hog." In

our treatment of the art of curling we shall bear this in mind; and, without

entering too minutely into technical and mathematical niceties, or

attempting to explain the miraculous feats by which the highest fame has

been achieved, we shall try to bring all curlers into the "parish" or "the

way of promotion," leaving them to become "perfect patlids " by dint of

their own genius and ambition. There are no curling professionals; the game

does not admit of them; it is better without them. Nor in curling is there

any code of hard and fast rules by which a knowledge of the art is to be

attained. The art is too fine for that. It is only by practice that any

degree of perfection can be reached. An ounce of experience is worth more

than a pound of instruction. But there are certain general rules and

principles which the collective experience of curlers has laid down to

regulate the curling art. The general rules we shall here give as they are

found in the Royal Club Annual. [With these may also be read the Rules for

District Medal Competitions (Appendix A, chap. vi.)] The general principles

we shall keep before us in discussing thereafter the various features of the

game and giving counsel to players. At the close of our -chapter we shall

give the rules for point play recently adopted by the Royal Club, which will

be found useful to the curler in giving him such practice and experience as

shall fit him for the higher stage of the bonspiel.

GENERAL RULES OF THE GAME.

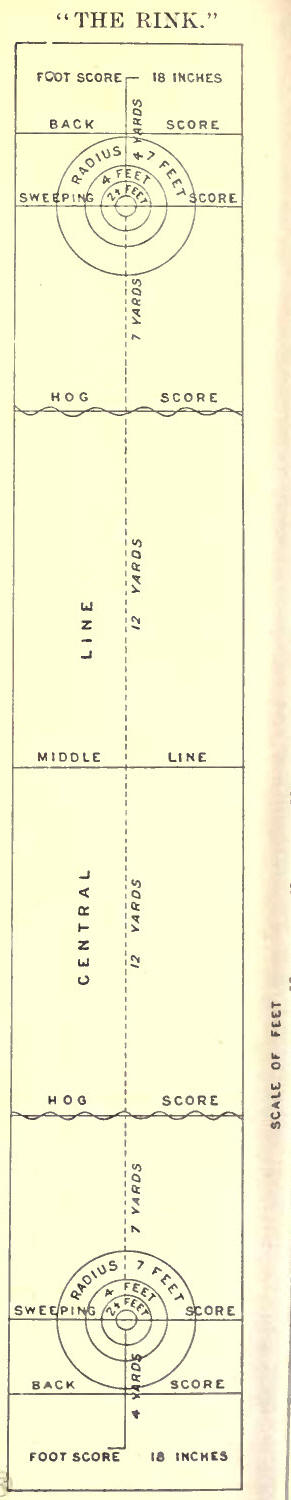

1. The length of

the rink for play, viz., from the back end of the crampit to the tee, shall

be 42 yards, and in no case less than 32 yards. Alterations are provided for

in Section 17. 1. The length of

the rink for play, viz., from the back end of the crampit to the tee, shall

be 42 yards, and in no case less than 32 yards. Alterations are provided for

in Section 17.

The tees to be set down 38

yards apart. Around each tee as a centre a circle of 7 feet radius shall be

drawn. (In order to facilitate measurements, 2 feet and 4 feet circles may

be laid down.) In exact alignment with both tees, a line, called the

"central line," shall be drawn, extending to a point 4 yards behind each

tee. At this point a line 18 inches in length, at right angles to the

central line shall be drawn, on which, and 6 inches from the central line,

the heel of craiupit shall be placed. The hack in this position shall be 3

inches from the central line, and shall not be more than 12 inches in

length.

Lines shall be drawn across

the rink at right angles to central line, as judicated in diagram, and

called ''hog scores," "sweeping scores," "back scores," and "middle score."

The hog score shall he placed

at one-sixth part of the entire length for play.

The sweeping score shall be

placed across the tees, for the use of the skips, and the middle score

midway between them, for the use of the players. (For regulation of sweeping

see sections 9 and 12.)

The back score shall be

placed just outside and behind the seven foot circle.

N.B.—Every stone shall be

eligible to count which is not clearly outside of the seven foot circle.

Every stone shall be a hog which does not clear the score, and must be

removed from the ice, but no stone to be considered as such which has struck

another stone lying in position. Stones passing the back line, and lying

clear of it, must be removed from the ice, as also any stone which in its

progress shall touch the swept snow on either side of the rink.

Note.—Reference in forming

rinks is made to the diagram or plan, called '"The Rink."

2. All matches to be of a

certain number of heads, to be agreed on by the clubs, or fixed by the

umpire, before commencement ; or otherwise, by time, or shots, if mutually

agreed on. In the event of parties being equal at the conclusion of the

match, play shall be continued by all the rinks engaged for another head;

or, if necessary to decide the match, for such additional heads as the

umpire shall direct.

3. Every rink to be composed

of four players a side, each using two stones. The rotation of play observed

during the first head of match shall not be changed.

4. The skips opposing each

other shall settle by lot, or in any other way they may agree upon, which

party shall lead at the first head, after which the winning party shall do

so.

5. All curling-stones shall

be of a circular shape. No stone, including handle, shall be of a greater

weight than 50 lb. imperial, or of greater circumference than 36 inches, or

of less height than one-eighth part of its greatest circumference.

6. No stone shall be changed

after a match has been begun, but the side of a stone may be changed at any

time during a match, provided sect. 10, chap. v., is adhered to.

7. Should a stone happen to

be broken, the largest fragment shall be considered in the game for that

end—the player being entitled to use another stone, or another pair, during

the remainder of the game.

8. If a played stone rolls

over, or stops, on its side or top, it shall be put off the ice. Should the

handle quit the stone in delivery, the player must keep hold of it,

otherwise be shall not he entitled to replay the shot.

9. Players, during the coarse

of each end, to be arranged along the sides, but well off the rink, as the

skips may direct ; and no party, except when sweeping according to rule,

shaII go upon the middle of the rink, or cross it, under any pretence

whatever. Skips alone to stand within the seven feet circle—the skip of the

playing party to have the choice of place, and not to be obstructed by the

other, in front of the tee, while behind it the privileges of both, in

regard to sweeping, shall be equal.

10. Every player to be ready

to play when his turn comes, and not to take more than a reasonable time to

play. Should he play a wrong stone, any of the players may stop it while

running; but if not stopped till at rest, the stone which ought to have been

played shall be placed in its stead, to the satisfaction of the opposing

skip.

11. If a player should play

out of turn, the stone so played may be stopped in its progress, and

returned to the player. Should the mistake not be discovered till the stone

be at rest, or has struck another stone, the opposite skip shall have the

option of adding one to his score, allowing the game to proceed, or of

declaring the end null and void. But if a stone be played before the mistake

has been discovered, the head must be finished as if it had been properly

played from the beginning.

12. The sweeping shall be

under the direction and control of the skips. The player's party may sweep

the ice from the middle line to the tee, and any of their own stones when

set in motion,—the adverse party having liberty only to sweep in front of

any of their own stones which have been set in motion by a stone played by

the opposite party. Both skips have equal right to clean and sweep the ice

behind the tee at any time, except when a player is being directed by his

skip. At the end of any head, either of the skips may call upon the whole

players to clean and sweep the entire rink, but being subject in this, if

objected to, to the control of the acting umpire. The sweeping shall always

be to a side ; and no sweeping shall he either moved forward or left in

front of a running stone. When snow is falling, the player's party may sweep

the stones of their own side from tee to tee.

13. If, in sweeping or

otherwise, a running stone he marred by any of the party to which it

belongs, it may, in the option of the opposite skip, be put off the ice ;

but if by any of the adverse party, it may be placed where the skip of the

party to which it belongs shall direct. If marred by any other means, the

player shall replay the stone. Should any played stone be displaced before

the head is reckoned, it shall he placed as near as possible where it lay,

to the satisfaction of, or by, the skip opposed to the party displacing. If

displaced by any neutral party, both skips to agree upon the position to

which it is to be returned ; but should they not agree, the umpire to

decide.

14. No measuring of shots

allowable previous to the termination of the end. Disputed shots to be

determined by the skips; or, if they disagree, by the umpire; or when there

is no umpire, by some neutral person chosen by the skips. All measurements

to be taken from the centre of the tee, to that part of the stone which is

nearest it.

15. Skips shall have the

exclusive regulation and direction of the game for their respective parties,

and may play last stone, or in any part of the game they please, but are not

entitled to change their position when once fixed. When their turn to play

comes, they may name one of their party to act as skip for them, and must

take the position of an ordinary player, and shall not have any choice or

direction in the game till they return to the tee head as skips.

16. If any player engaged or

belonging to either of the competing clubs, shall speak to, taunt, or

interrupt another, not being of his own party, while in the act of

delivering his stone, one shot may be added to the score of the party so

interrupted, for each interruption, and the play proceed.

17. If from any change of

weather after a match has been begun, or from any other reasonable cause,

one party shall desire to shorten the rink, or to change to another ; and if

the two skips cannot agree, the umpire shall, after seeing one end played,

determine whether the rink shall be shortened, and how much, or whether it

shall be changed, and his decision shall be final. Should there be no acting

umpire, or should he be otherwise engaged, the two skips may call in any

neutral curler to decide, whose powers shall be equally extensive with those

of the umpire. The umpire, moreover, shall, in the event of the ice being in

his opinion dangerous, stop the match. He shall postpone it, even if begun,

when, in his opinion, the state of the ice is not fitted for testing the

curling skill of the players; and except in very special circumstances, of

which the umpire shall be judge, a match shall not proceed, or be continued,

when a thaw has fairly set in, or when snow is falling, and likely to

continue during the match. Nor shall it be continued when such darkness

comes on as prevents (in the opinion of the umpire) the played stones being

well seen by players at the other end of the rink. In every case the match,

when renewed, must be begun de novo.

The Rink:—The general rules

of the game, it will be noticed, give very particular directions as to the

proper construction of the rink or board. It is of great consequence that

these rules should be attended to, and that the rink should be correctly

drawn. There is no excuse for the club which plays on a board laid out in a

slovenly and imperfect way. The formation of the double rink, as shown in

the diagram, is the result of the experience of many generations of curlers,

and it is a visible sign of the unity of the brotherhood—it has been adopted

and is used in every country where the games is played. An imperfect form of

rink leads to an incorrect style of play. Fitting the tee is the first duty

of the player, and it is evident that this cannot be properly done if the

cramppit or hack is not related to the central line as the diagram requires.

We have seen many matches played where the measurements of the rink were

left entirely to the eye, and some clubs never trouble to draw a central

line. Such neglect implies disregard for scientific play, and no club which

wishes to attain distinction will be guilty of it, but will strictly observe

the rules which are so distinctly laid down. The shortening of the rink

allowed under the rules is rendered necessary by the arrogance of the

climate, which claims a right to interfere with a match without the consent

of the players, and to prohibit them from "making up" in a rink of forty-two

yards. It is a question whether too much has not been conceded to the

weather. A match should certainly not be played when the condition of the

ice makes the game one of brute force and not of skill.

The Choice of Stones.—To one

who wishes to excel in the art of curling the choice of a pair of

curling-stones is almost as important as the choice of a wife. It must not

be done "lightly or unadvisedly." To those who are about to choose their

channel-stanes before they begin their curl-in;, we certainly give the

advice of Punch to those about to marry—"Don't." The channel-stanes are made

for the curler, not the curler for the channel-stanes. It is only after he

has tried stones of different material, weight, and build, and has made

himself acquainted with the soles of stones, even more than with their

bodies, that the young curler is in a position to choose a pair for himself.

For a season or two his best plan will be to test the capabilities of the

various stones alongside of his own powers, to study the points of the game,

and discern with what kind of sole these can best be taken, and to find out

in what position in the rink he is most likely to be of use. He will then

know that truth in curling-stones, as in other companions, is of greater

value than beauty, which is only skin deep, that fitness is a better guide

than fancy, and he will choose accordingly. If the beginner carefully reads

the learned Professor's statements in our last chapter, he will know as much

about the materiel of curling-stones as is good for him. As to weight. The

maximum allowed in the "Royal" rules is 50 lb. (including handles). There

are very few stones of this weight in use on modern ice, and more than once

a petition to reduce this maximum has come before the representative

meeting. The average weight of curling-stones is now from 35 to 40 lb. There

are more below 35 lb. than there are above 40 lb., and between the two

weights we may safely say that three-fourths of the stones now in use are to

be found. In the famous rink of Lord Eglinton, John Napier, stud (;room, led

with a pair of 50 lb. stones; Robert Brown of Lileston carne next with a.

pair at 48 lb. Hugh Conn, auctioneer, played 46 lb. or 44 1b., as the

day might require; while his lordship skipped with a pair of 42 1b. This

rink in weight was above the average of its own period, and it is much above

the average of ours but in playing up to the maximum the Eglinton rink gives

us a capital idea of the relative weights suitable to the four players of a

rink. When so much can be done by polish to improve the running of stones,

Nye do not see the necessity for such a reduction of weight as some desire.

A "parish" of pigmies is no proof that skill has superseded force. We would

therefore prefer to see young curlers trying to climb up to the maximum

rather than to climb down to the minimum weight. At the same time a light

dour stone is a better stone to lead the ice than a heavy keen one. The

beginner must avoid choosing stones which are beyond his control, for he

cannot master the art if he is overbalanced by a too heavy implement. The

stone will no doubt lessen with years of play, but the years of the player

will tell even more upon his constitution, and he will therefore be wise to

select such stones as lie can command and play with ease through a match of

three or four hours' duration. In regard to the build of a stone, a

50-pounder is generally about 36 inches in circumference. This is also the

maximum allowed in the rules, while the height is not to be less than

"one-eighth part of its greatest circumference." The orthodox height of a

stone of maximum weight and circumference is generally about 6 inches. For a

40 lb. stone a circumference of 35 inches, and a height of about 5 inches,

gives a good build, and this proportion holds for other weights. Extremes of

height or breadth are bad, as both render the delivery of the stone

difficult and uncertain, and the curler must bear in mind that the diameter

of the stone will continually be diminishing under the blows it receives

upon its belt, so that in his choice lie had better err on the broad side.

The most important part of the curling-stone is its sole or bottom. Whatever

conclusion may be come to in regard to breadth and shape of bottom, one

thin(; Whist be guarded against, and that is a sharp ridge between the sole

and the upper part of the stone. A flat-edged stone throws the water up over

itself, and sits down under the shover: it collects the snow before it, and

any refuse that may be on the ice. On the other hand, the stone that is

gradually chaffered off or rounded wins its way through water like a duck,

end casts aside snow and refuse like the plough fixed in front of the wheels

of a locomotive. A favourite subject of discussion anon; the curling

authorities of the transition period was this: "Whether is a broad or a

narrow sole the best?" The broad sole was championed by Dr Somerville of

Currie, whose statement we may here quote:—

"Stones should all run on a

broad surface" inches in diameter at least. We committed great blunders here

at one time making our stones run on a small centre, some of them as narrow

as 3 or 4 inches; the consequence of which was that, running on so small a

centre, they quickly found every bias of the ice, and, however fairly set

on, often thus missed the object. This is cured by broadening to 1 inches,

for, running on so wide a centre, their motion is much more steady ; they do

not so quickly feel the bias of the ice, and of course are much surer in

their aim and more certain in their effects. I need not add that the stones

running in this wide centre must be of the keenest metal and of the finest

polish, otherwise it will require too much power to play them home to the

object intended. We don't, however, gain in power as we narrow in bottom,

for two sufficient reasons—first, because the narrower the surface the

deeper the pressure, just as a narrow wheel sinks deeper into the sludge

than one that is broad; and secondly, because when playing upon a narrow

centre you are obliged to use your force more cautiously, for fear of

overturning your stone altogether. This fact is further proved by my own

experience. I can play my present stone, 7½ inches in sole, better and

further than my former one of three."

With Dr Somerville Sir

Pickard Broun cordially agreed, and recommended broad soles to all curlers.

Dr Cairnie differed from these authorities, and recommended for keen ice a

running bottom of 4 or 5 inches; for dull ice, one of from 2 to 2½ inches,

which latter, he says, was generally adopted at Largs. Cairnie's

correspondent on the subject of "curling at Kilmarnock" says that

experiments there had proved that a sole of 6 inches, with a level of 1½ or

2 inches for running on, the rest of the sole being very gently rounded to

its edge, is best adapted for ice, in whatever state it may be ; and in

reply to 1)r Somerville, this gentleman goes on to add:-

"The advantage of a narrow

bottom is principally perceived on keen ice, when the stone does not sink at

all. On damp: ice, the broad, flat sole runs almost as well as the gently

convex one, which we are advocating. Dr Somerville's other objection of the

great danger of overturning stones running on a narrow level is proven, from

experience, to have no foundation. A curler may play for a whole season with

a stone of 6 inches of sole, running on even 1½ inch of level, without once

overturning it, and that with only ordinary care in delivery, provided it be

made of the approved slightly convex shape." [Cairnie's Essay, p. 71.]

The question so keenly

discussed was not unlike that propounded by King Charles—"Which is heaviest,

a dead or a live fish? " Conlomb in France, and Rennie in this country,

proved that the friction of one body passing along another is not influenced

by the extent of surface, but depends on the weight of the body. With stones

of equal weight, the retardation of friction is therefore the same. The

distance each will travel depends on the initial velocity, and not on the

size of the stone. With stones of different weight, the heavier stone has

the advantage: it presents, comparatively, less surface to air, or snow, or

water. If a player has command of his stone, so as to give it the requisite

velocity, the heavier it is the better on ice covered with slush or water;

while on keen ice, if its weight is not required to remove obstacles, it

keeps it from being too easily sent spinning when once it has settled down.

While we keep in mind that

friction is a uniformly retarding force, there is this, however, to be said

on the question of broad or narrow bottom. On keen and clear ice the broad

bottom certainly gives the

stone

more stability, and prevents it from too readily taking biases; while on

spongy ice, or where there is snow or slush on the rink, the narrow bottom

cuts more easily down to the hard ice below, thereby diminishing the

friction, which is, of course, less on a hard than on a soft surface. The

fact that there were two sides to the question led to the conclusion that

there should be two sides to the curling-stone. Nearly all the stones are

now made with reversible soles—the one for keen, the other for baugh ice. In

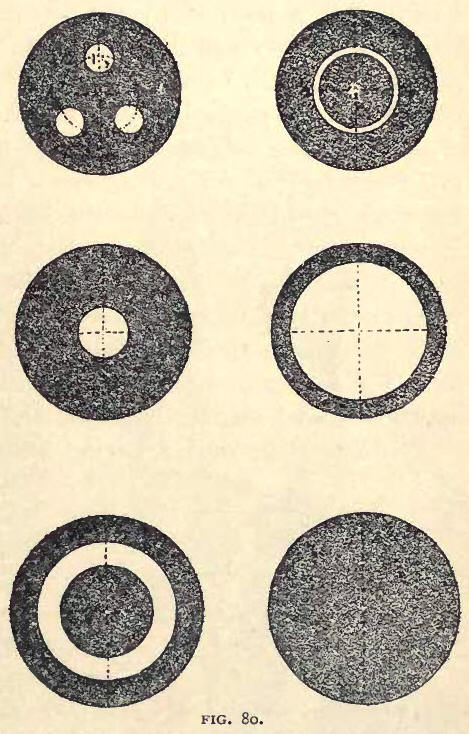

the transition period there was great variety of bottom among

curling-stones, as may be inferred from some drawings here given from

Cairnie (Fig. 80). The white portion of each disc is meant to indicate the

running portion of the sole of the stone; the dark disc representing the

upper side of a one-soled stone, while the two upper pairs of discs show the

opposite sides of double-soled stones. The stone with the uppermost pair of

soles was a favourite at Wishaw. It was the stone which "ran on feet" in the

match of Cam'nethan against Bathgate (videp.182). There can be nothing new

in curling-stone soles. Steel, brass, and lead have all been tried, and iron

stones like those now used in Canada were, in the transition period,

manufactured by the Shotts Iron Co., tried and discarded as unsuitable on

our ice. Among stone-players in Canada the stone now in general use has a

concave or hollow on both sides. The hollow of the dull side is generally

about 5 inches in diameter, with a depth at the centre of ¼ inch, and the

running ridge or ring is narrow and sharp, so as to grip the hard ice. The

hollow of the keen side is neither so wide nor so deep. The diameter is

generally about 2½ inches, and the running ridge is not sharp, but rounded

and smooth. In the home country a good many stones of the Canadian pattern

are in use, but the keen side of the stone is very often convex, gently

rounding to a pivot centre of 1½ or 3 inches, on which the stone runs, while

the dull side has a concave of about 4 inches diameter, and the running;

ridge not so sharp as in the Canadian. We can commend this doubly-modified

form. On keen days the concave keeps the ice well; and on dull ones the

convex lends itself readily to "kiggle-caggle"—or the oscillating motion

which skilful players who want to reduce friction communicate to their stone

on very laugh ice. A good many flat-bottomed stones are still in use. Our

countrymen have not come to any common understanding as to the best form of

sole. It is not quite a case of tot homines quot sententiœ; but there is

much difference of opinion. The beginner in the art must therefore examine

and judge for himself, and choose a pair of stones when he has made up his

mind as to the best material and outline. It will greatly increase his

enjoyment of curling if he is careful to attend to the polish of the stones.

His calculations may all be upset if this is neglected. He will have more

delight in their companionship if he now and then send his curling-stones to

the manufacturer to have their appearance and manners polished and improved. stone

more stability, and prevents it from too readily taking biases; while on

spongy ice, or where there is snow or slush on the rink, the narrow bottom

cuts more easily down to the hard ice below, thereby diminishing the

friction, which is, of course, less on a hard than on a soft surface. The

fact that there were two sides to the question led to the conclusion that

there should be two sides to the curling-stone. Nearly all the stones are

now made with reversible soles—the one for keen, the other for baugh ice. In

the transition period there was great variety of bottom among

curling-stones, as may be inferred from some drawings here given from

Cairnie (Fig. 80). The white portion of each disc is meant to indicate the

running portion of the sole of the stone; the dark disc representing the

upper side of a one-soled stone, while the two upper pairs of discs show the

opposite sides of double-soled stones. The stone with the uppermost pair of

soles was a favourite at Wishaw. It was the stone which "ran on feet" in the

match of Cam'nethan against Bathgate (videp.182). There can be nothing new

in curling-stone soles. Steel, brass, and lead have all been tried, and iron

stones like those now used in Canada were, in the transition period,

manufactured by the Shotts Iron Co., tried and discarded as unsuitable on

our ice. Among stone-players in Canada the stone now in general use has a

concave or hollow on both sides. The hollow of the dull side is generally

about 5 inches in diameter, with a depth at the centre of ¼ inch, and the

running ridge or ring is narrow and sharp, so as to grip the hard ice. The

hollow of the keen side is neither so wide nor so deep. The diameter is

generally about 2½ inches, and the running ridge is not sharp, but rounded

and smooth. In the home country a good many stones of the Canadian pattern

are in use, but the keen side of the stone is very often convex, gently

rounding to a pivot centre of 1½ or 3 inches, on which the stone runs, while

the dull side has a concave of about 4 inches diameter, and the running;

ridge not so sharp as in the Canadian. We can commend this doubly-modified

form. On keen days the concave keeps the ice well; and on dull ones the

convex lends itself readily to "kiggle-caggle"—or the oscillating motion

which skilful players who want to reduce friction communicate to their stone

on very laugh ice. A good many flat-bottomed stones are still in use. Our

countrymen have not come to any common understanding as to the best form of

sole. It is not quite a case of tot homines quot sententiœ; but there is

much difference of opinion. The beginner in the art must therefore examine

and judge for himself, and choose a pair of stones when he has made up his

mind as to the best material and outline. It will greatly increase his

enjoyment of curling if he is careful to attend to the polish of the stones.

His calculations may all be upset if this is neglected. He will have more

delight in their companionship if he now and then send his curling-stones to

the manufacturer to have their appearance and manners polished and improved.

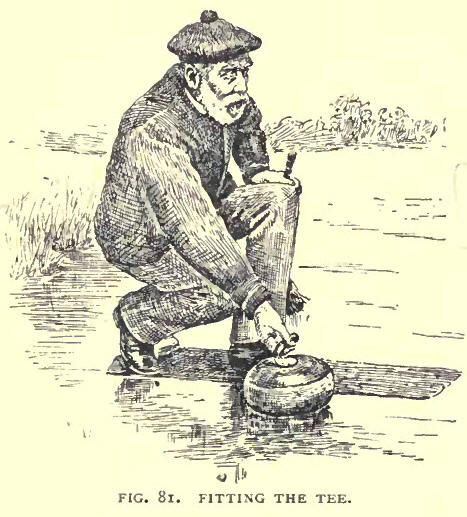

Position.—Our

curler having chosen a pair of suitable stones, must now prepare to play

them. In curl-ling, position is not quite "everything," but it is of primary

importance. Fit fair is the first command of the old curler's word.. There

are "divers manners" of doing this, as may be seen by looking at Figs. 81

and 82, where the players are caught in the act; but whatever position the

curler may assume, there must be no dubiety about his fitting the tee. This

is the absolute imperative of the curling position. To obey it, the player

must see that the crampit or hack is placed as directed in No. 1 of the

general rules. Looking toward the farther tee, he must then place his right

foot in the hack, the sole of his boot pressing against the perpendicular

back, and the ball of the great toe resting about the centre of the sloping

part : the left foot, as indicated at p. 161, lie will place at a right

angle about 18 inches forward. In playing from a crampit, the right foot

must, of course, rest against the back or fillet of the crampit. A good many

players place the left foot farther forward than we have indicated, and fit

their tee with the legs firmly poised like the sides of an equilateral

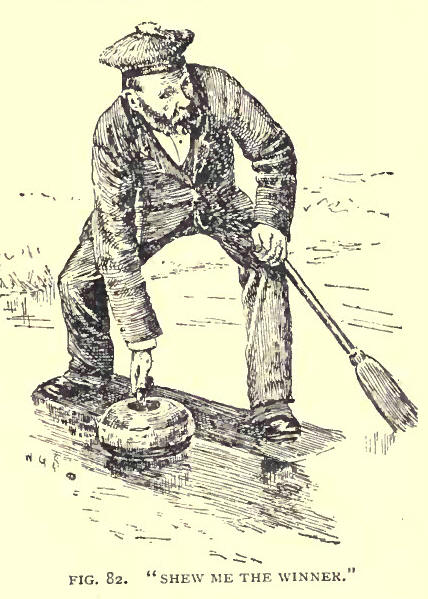

triangle, as in Fig. 82. We prefer the Position.—Our

curler having chosen a pair of suitable stones, must now prepare to play

them. In curl-ling, position is not quite "everything," but it is of primary

importance. Fit fair is the first command of the old curler's word.. There

are "divers manners" of doing this, as may be seen by looking at Figs. 81

and 82, where the players are caught in the act; but whatever position the

curler may assume, there must be no dubiety about his fitting the tee. This

is the absolute imperative of the curling position. To obey it, the player

must see that the crampit or hack is placed as directed in No. 1 of the

general rules. Looking toward the farther tee, he must then place his right

foot in the hack, the sole of his boot pressing against the perpendicular

back, and the ball of the great toe resting about the centre of the sloping

part : the left foot, as indicated at p. 161, lie will place at a right

angle about 18 inches forward. In playing from a crampit, the right foot

must, of course, rest against the back or fillet of the crampit. A good many

players place the left foot farther forward than we have indicated, and fit

their tee with the legs firmly poised like the sides of an equilateral

triangle, as in Fig. 82. We prefer the

couchant

position of the player in Fig. 81, as one in which there is greater purchase

over the stone. The curler must, however, poise himself in such a way as to

secure ease and accuracy in his play, and not be hampered by any fixed rule

as to position. The sine qua non is that he fit fair, and that no flank

movement be possible, as in the old days of movable triggers and crunching

crampits. The player must also decide for himself in what way he shall grip

the handle of the stone as lie prepares to swing it. Some do this in a

gingerly style, as if they were ashamed to touch the handle with the tips of

their fingers; others grip it as if they meant to squeeze the life out of

it: some grip from above, others from below. Some deliver with a side hand,

the thumb pressing on the back of the handle's neck; others, with the handle

at right angles to the central line, and pointing across their body (vide

Fig. 81), send it away to its destination in a free, open-handed manner. The

last method is the one we prefer when a straight shot has to be played. In

playing the "twist," of which more anon, the right-angle position, however,

puts rather a heavy strain on the wrist; and to relieve this, it is better

to modify the position of hand and handle as indicated in Fig. 82, where

(the player looking north) the thumb points north-east, and the twist to

left or right is played without any undue straining of the wrist in either

case. For a particular player that Method is undoubtedly the best which

enables him to perform most effectually the next function of the curling art

which falls to be considered, viz.: couchant

position of the player in Fig. 81, as one in which there is greater purchase

over the stone. The curler must, however, poise himself in such a way as to

secure ease and accuracy in his play, and not be hampered by any fixed rule

as to position. The sine qua non is that he fit fair, and that no flank

movement be possible, as in the old days of movable triggers and crunching

crampits. The player must also decide for himself in what way he shall grip

the handle of the stone as lie prepares to swing it. Some do this in a

gingerly style, as if they were ashamed to touch the handle with the tips of

their fingers; others grip it as if they meant to squeeze the life out of

it: some grip from above, others from below. Some deliver with a side hand,

the thumb pressing on the back of the handle's neck; others, with the handle

at right angles to the central line, and pointing across their body (vide

Fig. 81), send it away to its destination in a free, open-handed manner. The

last method is the one we prefer when a straight shot has to be played. In

playing the "twist," of which more anon, the right-angle position, however,

puts rather a heavy strain on the wrist; and to relieve this, it is better

to modify the position of hand and handle as indicated in Fig. 82, where

(the player looking north) the thumb points north-east, and the twist to

left or right is played without any undue straining of the wrist in either

case. For a particular player that Method is undoubtedly the best which

enables him to perform most effectually the next function of the curling art

which falls to be considered, viz.:

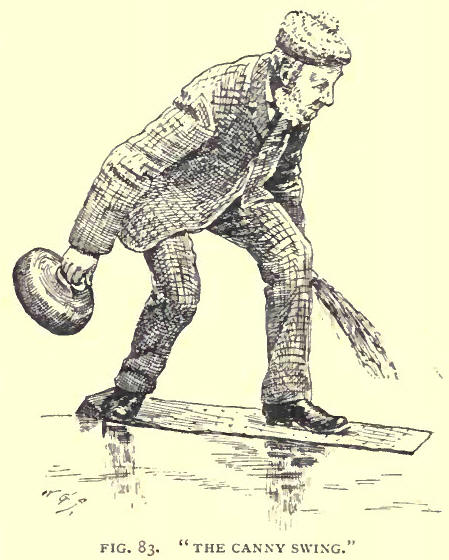

The Swing.—The curler must

exercise a wise economy by refusing to his stone of 35 or 40 lb. weight the

luxury of any "preliminary waggles" to prepare it for the swing. Such things

please the light-headed clubs of the golfer, and put them in good humour,

but the "stone of might" does not need to be coaxed in that way to do its

work. Near and sure is the motto of the rink, as Far and sure

is that of the links. For Keep your eye on the ball, the curler

substitutes Look at the mark with all your een. There must be no

looking down at the feet, or at the stone, or at some guiding point half-way

up the rink, when the swing is in course. The player must fix "a basilisk

glance" on the mark. The swing is to convey the life to the stone, and the

eye must communicate the information by which the mind of the player through

the swing determines what kind of life is needed. The hand is worked by the

head, and the head by the eye.

" Low o'er the weighty stone

He bends incumbent, and with nicest eye

Surveys the farthest goal, and in his mind

Measures the distance, careful to bestow

Just force enough."

The

golfing motto Slow back; (or, as Sir Walter Simpson would have it, Taut

bade) is a good one for the curling swing. "A cannie draw to the besorn." "Jist

tee-high weight." " annilie doun howe ice." To such direction the stone is

drawn slowly backward and upward, the body of the player rising gently in

unison with the swing till his weight rests on the right foot. It is poised

a moment, while more intently than ever the player's eye is fixed on the

mark. Then quietly the stone is brought back by the way it came, the body of

the player bending down, and his weight gradually coaling upon the left

foot. The force of the body is thus thrown into the arm and when the stone

meets the ice at the spot where it was lifted, it is instinct with life, and

moves away, "wi' a whirr and a curr,' to carry out its master's purpose. It

was "bonnilie laid down," the kowe smoothed its path : it vent snoovin' up

the hove and toddled ben to the tee—"a gran' shot, man; jist like yoursel'.The

canny swing for a drawing shot is that which is oftenest required in the art

of curling. When more than drawing The

golfing motto Slow back; (or, as Sir Walter Simpson would have it, Taut

bade) is a good one for the curling swing. "A cannie draw to the besorn." "Jist

tee-high weight." " annilie doun howe ice." To such direction the stone is

drawn slowly backward and upward, the body of the player rising gently in

unison with the swing till his weight rests on the right foot. It is poised

a moment, while more intently than ever the player's eye is fixed on the

mark. Then quietly the stone is brought back by the way it came, the body of

the player bending down, and his weight gradually coaling upon the left

foot. The force of the body is thus thrown into the arm and when the stone

meets the ice at the spot where it was lifted, it is instinct with life, and

moves away, "wi' a whirr and a curr,' to carry out its master's purpose. It

was "bonnilie laid down," the kowe smoothed its path : it vent snoovin' up

the hove and toddled ben to the tee—"a gran' shot, man; jist like yoursel'.The

canny swing for a drawing shot is that which is oftenest required in the art

of curling. When more than drawing

weight

is needed, the height and force of the swing must be increased. weight

is needed, the height and force of the swing must be increased.

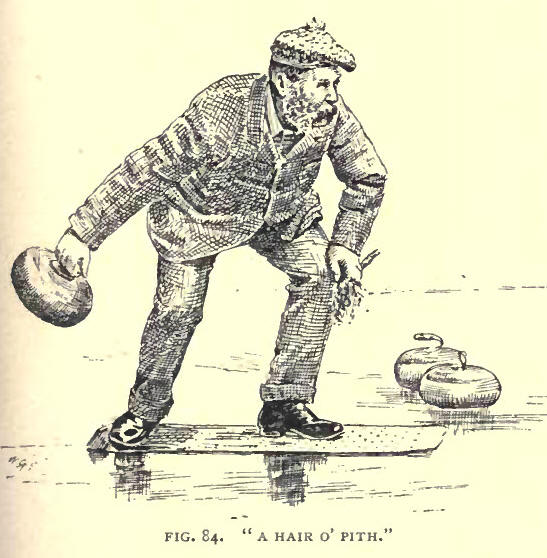

"There's a truck o' Benhar

blockin' the line, laird; ye maun remove 't in your ain quiet way." Such is

the direction we have heard given when a fifty-pounder of the enemy had

settled down in front of the tee. The player in that case had to put on a

little steam, and he knew how to do it. This was the laird's quiet way (Fig.

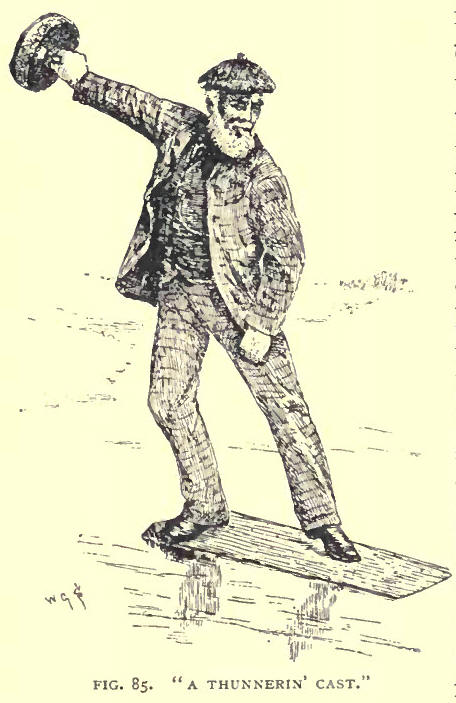

84). Curlers in olden times did not worship the "canny swing." They believed

more in the swing maximum, which is uncanny. He was the greatest hero who,

when occasion required, could best display

"The might that slumbers in

the yeoman's arm."

To rebut or drive a

thunderbolt up among double and

treble guards when the game was hopeless or desperate, and to cannon, or

male a guard butt off the

winner

and follow in so as to lie shot, were two favourite points by which the

ancient curlers were wont to win distinction. "Often," says Sir R. Broun,

"from the opposite end of the rink have we seen the sole of our president's

stone over his head when he had to lift up double guards." William Gourlay

and Aleck Cook must have excelled at these shots. They are not much played

in our cultured and skilful age, but occasions do occur when the player must

rise to the highest height of endeavour. "A' the pouther i' the horn." "Come

doun winner

and follow in so as to lie shot, were two favourite points by which the

ancient curlers were wont to win distinction. "Often," says Sir R. Broun,

"from the opposite end of the rink have we seen the sole of our president's

stone over his head when he had to lift up double guards." William Gourlay

and Aleck Cook must have excelled at these shots. They are not much played

in our cultured and skilful age, but occasions do occur when the player must

rise to the highest height of endeavour. "A' the pouther i' the horn." "Come

doun

"Long swings the stone,

Then with full force, careering furious on,

Rattling it strikes aside both friend and foe,

Maintains its course and takes the victor's place.

Such flights of the art we

cannot follow, nor can we show how they may be taken. When a curler has to

raise his stone above his shoulder, his moral responsibility is at an end,

and his brethren must take care of him.

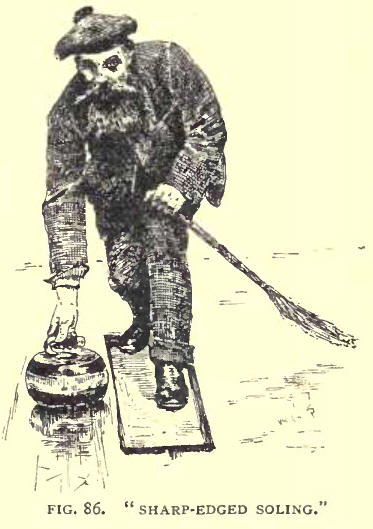

Soling

and Delivering the Stone.—When the curler does not swing back his stone

properly, but lifts it straight up, he will in delivering clink it on the

ice and break its back. Again, he may swing the stone quite correctly, but

if he do not sole it properly, the force and effect of the swing will be

destroyed. The proper soling of the stone is of great importance. A stalwart

player who cannot sole his stone is nowhere against a man of half his power

who has the secret of "a quid delivery." The chaffering of the stone to

which we have referred is of great consequence for correct soling.

Sharp-edged stones must be put down with great nicety and caution if the

player would avoid mangling the ice and spending; the stone. By letting go

the stone too soon he will dump its forehead on the ice, and by holding on

to it too long he will do the same with the back edge, and either way the

.stone will be image to wobble. The curler must guard against this by

letting the stone gently off his hand as soon as it meets the ice. It is

right that every curler should watch with interest the career of the stone

after it has left his hand. Nor is there any law to prevent him sheaving his

mental anxiety by various bodily contortions. We rather admire than condemn

the eager gamester who, after the act of delivery, Soling

and Delivering the Stone.—When the curler does not swing back his stone

properly, but lifts it straight up, he will in delivering clink it on the

ice and break its back. Again, he may swing the stone quite correctly, but

if he do not sole it properly, the force and effect of the swing will be

destroyed. The proper soling of the stone is of great importance. A stalwart

player who cannot sole his stone is nowhere against a man of half his power

who has the secret of "a quid delivery." The chaffering of the stone to

which we have referred is of great consequence for correct soling.

Sharp-edged stones must be put down with great nicety and caution if the

player would avoid mangling the ice and spending; the stone. By letting go

the stone too soon he will dump its forehead on the ice, and by holding on

to it too long he will do the same with the back edge, and either way the

.stone will be image to wobble. The curler must guard against this by

letting the stone gently off his hand as soon as it meets the ice. It is

right that every curler should watch with interest the career of the stone

after it has left his hand. Nor is there any law to prevent him sheaving his

mental anxiety by various bodily contortions. We rather admire than condemn

the eager gamester who, after the act of delivery,

"Bends

His waist, and winds his hand, as if it still

Retained the power to guide the devious stone."

But

this kind of thing may easily be overdone. In the jeu d'esprit, Uloseburn v.

Loclimaben, Professor Gillespie introduces " a fat, round, oily bailie, with

his beetle legs and bald head, who lay flat upon the ice eyeing up his

stone, and writhing from side to side, as if in the act of determining its

direction." It is said that James Millar, advocate, who was such a popular

player in the Duddingston Club, used regularly to squat on his belly on the

middle of the rink after the stone went off, and kick, roar, sputter, and

gesticulate wildly after it, to the infinite amusement of the numerous

onlookers, some of whore were shocked to see a learned member of the Faculty

of Advocates so conducting himself. We have seen some who came pretty near

to this, and many make a practice of following the stone halfway up the

rink. The reason why some players run forward so absurdly is to recover

their balance after the stone is delivered. This would not be necessary if,

according to the custom of the best players, the left foot were lifted and

slightly advanced as the stone is sent away. In the delivery the centre of

gravity of the player is advanced, and by moving forward the left foot his

base line (so to speak) is also advanced, and his stable equilibrium

preserved. While we would not have curlers to be too self-conscious, or to

refrain from manifestations of enthusiasm in case the may be laughed at, we

would remind their of the rules which say that they must not take more than

"a reasonable time" to play their stone, and that "no party, except when

sweeping according to rule, shall go upon the middle of the rink, or cross

it, under any pretence whatever." If they must step off the crampit in their

eagerness to see their stone ushered in to victory, let then do so as

gracefully as the veteran curler in Fig. 88, and we shall forgive them. But

this kind of thing may easily be overdone. In the jeu d'esprit, Uloseburn v.

Loclimaben, Professor Gillespie introduces " a fat, round, oily bailie, with

his beetle legs and bald head, who lay flat upon the ice eyeing up his

stone, and writhing from side to side, as if in the act of determining its

direction." It is said that James Millar, advocate, who was such a popular

player in the Duddingston Club, used regularly to squat on his belly on the

middle of the rink after the stone went off, and kick, roar, sputter, and

gesticulate wildly after it, to the infinite amusement of the numerous

onlookers, some of whore were shocked to see a learned member of the Faculty

of Advocates so conducting himself. We have seen some who came pretty near

to this, and many make a practice of following the stone halfway up the

rink. The reason why some players run forward so absurdly is to recover

their balance after the stone is delivered. This would not be necessary if,

according to the custom of the best players, the left foot were lifted and

slightly advanced as the stone is sent away. In the delivery the centre of

gravity of the player is advanced, and by moving forward the left foot his

base line (so to speak) is also advanced, and his stable equilibrium

preserved. While we would not have curlers to be too self-conscious, or to

refrain from manifestations of enthusiasm in case the may be laughed at, we

would remind their of the rules which say that they must not take more than

"a reasonable time" to play their stone, and that "no party, except when

sweeping according to rule, shall go upon the middle of the rink, or cross

it, under any pretence whatever." If they must step off the crampit in their

eagerness to see their stone ushered in to victory, let then do so as

gracefully as the veteran curler in Fig. 88, and we shall forgive them.

Sweeping.—According

to Shakespeare, "to smoothe the ice " is as much a work of supererogation as

"to gild refined gold" or "to paint the lily." .Ne sutor ultra crepidam. We

do not expect a dramatist to know the advantage of "soopin'." In the art of

curling no man can ever excel who does not learn "to smoothe the ice." It is

the broom that wins the battle. Every good curler knows that. Neither age

nor dignity exempts a player from the duty of sweeping. As far as our

experience goes, neither the old nor the noble require to be reminded of it.

The Nestor of a club is generally the member who believes most in the virtue

of elbow-grease, for he has oftenest been witness of its good effects. We

have seen the present Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly (the

Marquis of Tweed-dale) plying his broom on the frozen Tyne as nimbly as his

humblest retainer, and thus helping the Yester men to win the county cup. It

is the young roan of the period who requires to be taught his duty in this

respect. Ile curls—because it is fashionable ; he has a broom, but he might

as well be without it, for when lie steps off the crampit he puts it under

his arm, and with his pipe in this teeth and his hands in his pockets he

sludges about the edge of the rink till his turn to play again comes round.

One fellow of that kind in a rink will ruin its chance of winning the match.

He ought simply to be put off the ice and expelled from all respectable

curling society. After he has taken his place on the crampit every curler

should give the soles of his stones a rub to see that no dirt or snow

adheres to them ; he should then give the ice in front of him "a bit soop."

When his stone has been played he ought to take his place among the

sweepers, and with his besom ready for action, await the skip's direction.

In olden tunes, when there were eight players on each side, the orderly

arrangement of the sweepers was no easy matter. The following account of the

Wanlockhead curlers shows how effective such arrangement was, and how much

attention was given by ancient curlers to this department of their work:- Sweeping.—According

to Shakespeare, "to smoothe the ice " is as much a work of supererogation as

"to gild refined gold" or "to paint the lily." .Ne sutor ultra crepidam. We

do not expect a dramatist to know the advantage of "soopin'." In the art of

curling no man can ever excel who does not learn "to smoothe the ice." It is

the broom that wins the battle. Every good curler knows that. Neither age

nor dignity exempts a player from the duty of sweeping. As far as our

experience goes, neither the old nor the noble require to be reminded of it.

The Nestor of a club is generally the member who believes most in the virtue

of elbow-grease, for he has oftenest been witness of its good effects. We

have seen the present Lord High Commissioner to the General Assembly (the

Marquis of Tweed-dale) plying his broom on the frozen Tyne as nimbly as his

humblest retainer, and thus helping the Yester men to win the county cup. It

is the young roan of the period who requires to be taught his duty in this

respect. Ile curls—because it is fashionable ; he has a broom, but he might

as well be without it, for when lie steps off the crampit he puts it under

his arm, and with his pipe in this teeth and his hands in his pockets he

sludges about the edge of the rink till his turn to play again comes round.

One fellow of that kind in a rink will ruin its chance of winning the match.

He ought simply to be put off the ice and expelled from all respectable

curling society. After he has taken his place on the crampit every curler

should give the soles of his stones a rub to see that no dirt or snow

adheres to them ; he should then give the ice in front of him "a bit soop."

When his stone has been played he ought to take his place among the

sweepers, and with his besom ready for action, await the skip's direction.

In olden tunes, when there were eight players on each side, the orderly

arrangement of the sweepers was no easy matter. The following account of the

Wanlockhead curlers shows how effective such arrangement was, and how much

attention was given by ancient curlers to this department of their work:-

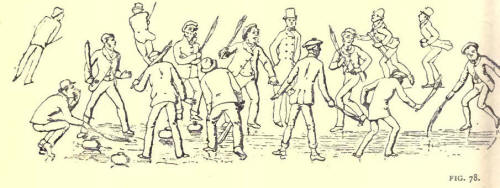

Almost without exception,

tall, strapping young men, strong and hardy, they possessed every quality

necessary to make good curlers. Their discipline, too, was absolutely

perfect. At the time when there were eight men in a rink this was most

apparent. Arranged three and three on each side of the rink, they waited

with the greatest attention till the stone was delivered, following it

quietly but eagerly in its course, till, at the call of the skip, 'Soop her

up,' down came the besoms like lightning, hands were clasped, the feet kept

time to the rapid strokes of the besom, and no exertion was spared until the

stone was landed at the desired spot, when a good long breath being drawn,

the player was rewarded with a universal shout, `Weel played, mon.' Dispute

as we may as to the relative merits of the different parishes as to curling

in the general, we believe that all who have seen Wanlockhead curlers play

will admit that in the matter of sweeping they 'bear the gree. [Brown's

History of the Sanquhar Curling Society, p. 29.]

In the modern rink of four

players the skip must look after the boardhead, and two only are left to

sweep between the middle line and the boundary of the parish, when the

fourth is on the crampit. Elaborate arrangement of the sweeping department

is therefore unnecessary. For a long •time the law was that "parties, before

beginning to play, must take different sides of the rink, which they must

keep throughout the game." This, however, was rescinded, and the practice is

now to sweep from either side; but it is still important that order and

discipline should be maintained, and that strict attention be paid to the

duties of the besom. The rule that "all sweeping must be to the side" still

holds, and the kowe must never be used to put obstacles in the way of the

stone. The earlier law of the Royal Club prohibited sweeping until the stone

had reached the hog. In Sir George Harvey's Curling Match the players are

seen sweeping from tee to tee. The painter on being challenged defended his

picture as a faithful representation of the old custom. And so it is. Lord

Eglinton and the Ayrshire curlers stuck out for this old system, and in 1852

a compromise was arrived at by which sweeping was allowed from the "middle

line " and from tee to tee if snow should be falling during the play. It is

the duty of the sweeper to abide by the order of the skip, who only can

determine whether or not sweeping is necessary; and when "Ne'er a kowe" or

"Brooms up" is sounded he must be as ready to stop as he is to begin when

the cry of "Soop, lads, soop," is heard. It is in the power of either skip

to call upon all the players at the close of an end to clean the rink. This

should never be taken advantage of simply to delay a match, but it is right

that the game should always be conducted on a clean board, and every club

ought to avoid the necessity for any such delay by keeping the rink in good

condition, and acting up to the old motto

"QUHAIR EUER THEY GO IT MAY BE

SENE

HOW RINK AND TEE THEY BOTH SOOP CLENE."

The Twist.—To be able by a

turn of the wrist to give the stone a rotatory motion which shall make it

run against the bias of the ice, or to transform an object of offence into

one of defence by making the stone curve round the right or the left side of

a guard by an elbow out or elbow in delivery, is one of the highest

accomplishments in the art of curling, and greatly increases the interest

and skill of the player. This secret is said to have been discovered at

Fenwick in the first year of the century, [Vide Taylor's Curling, p. 69.]

and it is therefore generally called the Fenwick Twist.

Now, there may be no harm in

connecting the twist with Fenwick, that famous centre of keen curling since

the days of Covenanter Guthrie. But we are not sure that the origin of the

twist is any clearer than the origin of the Royal Club or of curling itself.

The name of Kilmarnock is sometimes attached to it, but this may simply be

on the principle that the (greater includes the less. The Cambusnethan

curlers hold that the secret of the "turn of the hand" was known there about

the end of last century, and that it was the discovery of William Bell,

grandfather of the present patron of the Buchan Club, Robert Bell of

Cliftonhall. In a match played against Lesmahagow at Garionhaugh, near

Dalserf, 24th January 1809, the Cam'nethan curlers are said to have

distinguished themselves by this scientific style of play, and Lesmahagow

and other parishes are said to have acquired the secret from Cam'nethan.

[Captain Paterson, in the

Douglas Bonspiel, p. 9 (1806), refers to some curlers

"Who can, with subtle wrist,

Give to their stave the true `Kilivarnock twist."'

This reference, if it does

not settle the question, bears strongly against the Cain'nethan theory.]

Now, we are quite convinced

that the secret of the twist was discovered long before the end of the last

century, and that some of the remarkable feats of curlers in ancient times

were accomplished by the aid of what is now called the Fenwick Twist. Among

the sons at the end of Cairnie's Essay (P. 133), there is one said to have

beets composed extempore, in 1784, at the match between the Duke of Hamilton

and M`Dowall of Castlesemple. In this song there occurs the following

stanza:---

"Six stones within the circle

stand,

And every port is blocked,

But Tarn Pate he did turn the hand,

And soon the port unlocked."'

[In the Sketch of Curling,

published at Kilmarnock in 1828, the song, considerably altered and

enlarged, appears above the signature of "J. Bicket, Fenwick." The reference

to Tarn Pate is there omitted. Cairnie's version is certainly the best.]

Who is so foolish as to

suppose that 2Car'loc1 Tam had not the twist among his secrets ? Some would

;o a long way farther back and find in the word curl itself a proof that the

ancients could turn the hand and bend the course of the stone even without a

handle. This much having been said for the antiquity of the twist, we must

acknowledge that the old curling word (lid not notice this style of play.

Its command Sias—Shoot staight. With obedience to this command the practice

of the twist does not, however, interfere. Paradox though it may appear, a

curler who cannot shoot straight cannot put on the proper curl. To be able

to shoot straight is to be able to deliver the stone without any rotatory

motion. Before we can deliver the stone with such a rotatory motion as we

wish to give it, we must first be able to protect it from taking a rotatory

motion which we do not wish to give it. The young curler should therefore

obey the old word, and he should never play the twist until he is able to

shoot straight. A good straight player is a good curler. On some kinds of

ice he will hold his own against the most efficient practitioner of the

Fenwick twist. No curler is, however, entitled to be reckoned a graduate of

arts in curling until he has mastered the knowledge of the in-turn and the

out-turn. When he begins to try these his play will very likely deteriorate,

lie will go off his game in trying to get on with it. This is a common

occurrence. Experience of the kind has discouraged many a player, and made

him condemn the fiord altogether. If the young curler has the pluck to

persevere; if he lose no opportunity of having a quiet practice and studying

the curve made by each kind of sole; if he carefully guard himself against

losing his power to play the straight game, while he is trying to master the

other style of play, he will find his patience amply rewarded. Occasions

will arise when the power thus gained will stand him in good stead. He will

triumphantly sail up the howe when his neighbour is driven helplessly aside

by the bias, and the straight player will be completely dumfoundered at

seeing his wily opponent remove the winner which he had thought impregnable,

for

"By the turning of the hand

All guarding's but a mock."

In the twist, as in other

departments of the art, practice is the only way to perfection. pile the

direction given by the skip is elbow in or elbow out, the player must

remember that it is the wrist that communicates the twirl to the stone. This

should be given just at the moment when the stone in its downward swing

makes a tangent with the ice. The old order Shoot straight is, as we have

said, quite consistent with putting on curl. The player must not swing his

stone toward the right or the left when he wants it to turn to the one or

the other, but it must be sent off straight toward the mark. The twist will

direct it in the desired curve, and its effect will be felt most in the

dying moments of the stone's career.

Skipping a Rink.—The goal of

a curler's ambition is to become a skip. For this high office not only

masterly play but the best qualities of head and heart are required. The man

who can skip a rink well may rule a kingdom. With the club it lies to

determine upon whom the honour is to be conferred, and this is usually done

at the annual meeting. In choosing their skips clubs cannot be too careful,

for upon this choice their reputation very much depends. There should be no

flunkeyisin, and no hole-and-corner work. All should be fair and square, and

the skip should be chosen on his merits, not because he is patron,

president, or chaplain of his club. The best curler in the club often plays

in homespun. Clubs should appoint skips ad vitam aut culpam, and not

change them every year, unless they are found guilty of intemperance,

ill-nature, or the driving game. The choice of players should be left to the

skips, and these again should not be annually disarranged, but vacancies

should be filled up as they occur, and the continuity of the rink preserved.

The skip will place his men according to their powers—the lead, one who can

draw with a stone of weight; the second, one who can guard well; the third,

a player who can take brittle shots and put on the curl when it is needed.

Esprit de corps is a grand thing in a rink. The quartet must work well

together, and be attached to each other and to their head. In America they

have a Four-brother club, which is made up of family rinks, to illustrate

the advantage of keeping together. We have seen on the Dalkeith pond a

display of fine curling by a rink of four brothers, who knew each other's

play to a tee, and worked as if they had discussed every situation together

the night before, and settled how to act.

We may talk of equality on

the ice, but not in presence of the skip. The Autocrat of all the Russias is

not more absolute in his sway than the doupar or director of a rink of

curlers.

"The skipper's advice is

imperative law."

To this very end he is

elected, that he may dictate what is to be done, and it is his duty to brook

no interference with his rule. When he gives orders, he must see that they

are obeyed. But while a skip must rule with a rod of iron, and allow no one

to question his direction, he must deal gently with the erring, and must not

flyte when a player misses a shot. "That's no like you;" "It's no very often

ye dae that;" "As guid as a better;" or "Ye'll get it next time," are

remarks more likely to improve the form of the player than a volley of

abuse. The skip should believe that his men are always doing their best; and

even when the battle is going against him, he must not sulk, or sputter and

foam at friends and enemies alike, as the manner of some is. Curling is a

slippery game, and many a match has been saved at the eleventh hour by the

splendid courage of the skip who never played better than when he was

playing a losing game. And oh, the victories which have been gained by dint

of praise! How it puts mettle into the men and fires their enthusiasm, and

cheers them on to victory, when the skip sings out his salutations in such

phrases as these, which have gladdened the hearts of keen curlers in every

age: "You for a curler;" "Come up an' look at it;" "You're the king o'

players;" "Gie's a shake o' your hand;" "I'll gie ye a snuff for that."

There is no end to the

resources which a skip may call into play. He must never allow the attention

of the players to ila-, for a quick rate of game is generally most

effectual. To carry on the game with proper speed, the skip must take in the

situation at once, and not dawdle about the "parish" till the "thow " comes.

He must at the outset of a match "tak' up the ice "--i.e., judge of any bias

there may be, and how best to counteract it; and he must be prompt and

decided in his orders, never giving two or three directions at one time, and

so confusing the player. We must not suppose that a rattling game requires a

raging style of play. For all ordinary purposes tee-high weight is enough

for a stone. Curling cannot be played on bare rink-heads. A good skip will

therefore avoid the drilling or striping game. Shakespeare must have been a

curler after all, for we find him warning skips in these words:-

"We may outrun

By violent swiftness that which we run at,

And lose by over-running."

But skips must not quote

Shakespeare. If they must have a motto for quiet play, let it be that of

Boswell's Dammabak,

"A gude calm shot is aye the

best."

Or, better still, that fine

old saying, Oh, be cannie! It is to our skips that we must look to

preserve pure the auld Scotch phrases and words which connect the game with

bygone times, and to make the rink a sanctuary of refuge for the zither

tongue when every other comes to be shut against it. To our skips we also

look- to preserve the venerable and time-honoured traditions of the noble

game : to maintain its high tone, and never to permit anything that is vile,

or low, or ungentlemanly to disfigure the beauty of it.

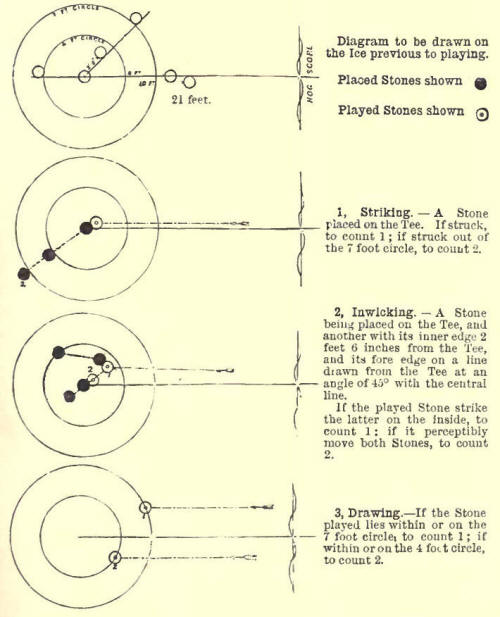

RULES FOR LOCAL MEDAL

COMPETITION.

POINT GAME. ADOPTED 1888

1st. Competitors shall draw lots for the rotation of play, and shall use two

stones.

2nd. The length of the rink

shall not exceed 42 yards; any lesser distance shall be determined by the

umpire.

3rd. Circles of 7 feet and 4

feet radius shall be drawn round the tee, and a central line through the

centre of the 4 foot circle to the hog score.

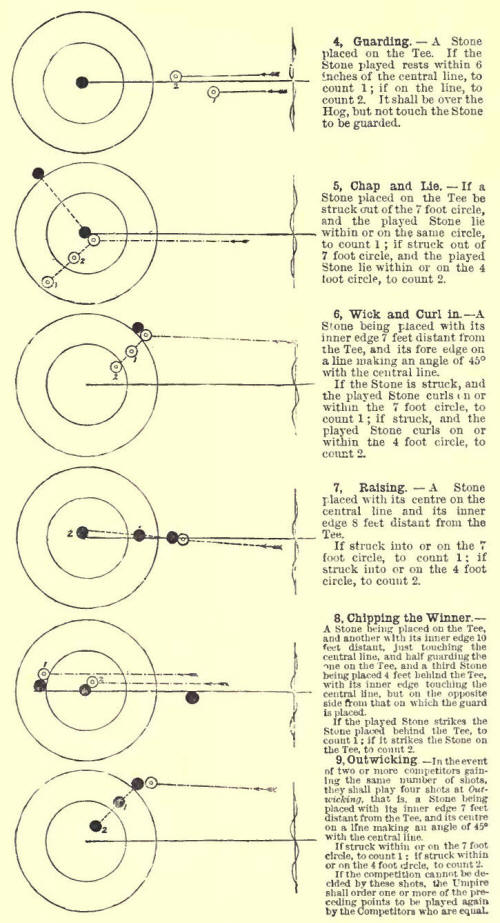

4th. Every competitor shall

play four shots at each of the eight following points of the game,

viz.:—Striking, inwicking, drawing, guarding, chap and lie, wick and curl

in, raising, and chipping the winner, according to the following

definitions. (See below.)

5th. In Nos. 2, 6, 8, and 9,

two chances on the left and two on the right.

6th. No stone shall be

considered without a circle unless it is entirely clear of that circle. In

every case a square is to be placed on the ice to ascertain when a stone is

without a circle, or entirely clear of a line.

NOTE.—The above rules and

definitions are applicable only to medals given by the Royal Club, and are

not intended to supersede any regulations made by local clubs in competing

for their own private medals.

NOTE 2.—It will save much

time if, in playing for local medals, two rinks be prepared lying parallel

to each other, the tee of the one being at the reverse end of the other

rink; every competitor plays both stones up the one rink, and immediately

afterwards both down the other, finishing thus at each round all his chances

at that point.

It will also save time if a

code of signals be arranged between the marker and the players, such as the

marker to raise one hand when one is scored, and both hands when two are

scored. In the ease of a miss hands to be kept down.

Of the point game as a test

of skill we have given our opinion in a former chapter. It is the skeleton

of the curling system. The living figure of curling can only be studied in

the bonspiel. For practice it is,

however,

invaluable; and by point play curlers may prepare themselves for the higher

art. They may by such practice test the various rules which we have laid