|

THE original parish church of

Culross, known as the West Kirk, is situated nearly a mile west by north of

the Abbey Church, on the old road leading through the moor to Kincardine.

Nothing whatever is known of its early history, beyond the information,

already detailed, contained in the Act of the Scottish Parliament of 1633,

which finally stripped it of its dignity as the parish church, and

transferred this status to the Abbey Church, which had practically and

solely served this function ever since the Reformation.

The West Kirk had thus never

witnessed within its walls any other services than those of the Roman

Catholic faith. It probably dates its origin from the first division of

Scotland into parishes, which is sup* . posed to have taken place in the

twelfth century, in the reign of David I. The primitive rudeness of its

architecture warrants us in referring its erection to a very remote period,

the style of building approximating very closely to those ancient edifices,

few in number, which are still to be found in England, and have been classed

under the denomination of Early Saxon. Its dimensions are small, having a

length from east to west of about sixty-eight feet, and a breadth of

eighteen feet. The only part of the walls that remains tolerably entire is

on the east and south sides. The latter contains a low and primitive

doorway, with jambs and lintel, unprovided with any ornament; and

immediately adjoining it, on its west side, is a narrow aperture or window,

once surmounted by a plain pointed arch. This last is the only remaining

object in the architecture of the West Kirk that preserves a distinctly

ecclesiastical character, if we except two large stones sculptured with

crosses. These have been built into the walls, one of them serving as a

lintel for the doorway just mentioned, and the other as that of a plain

window three feet square on the north side. It seems difficult to account

for their situation in their present position, unless we suppose them to

have been originally tombstones, and that in Protestant times the ruined

church may have been used as a burial-place, and the decaying walls patched

up with those relics of a past age. By some the sculptures in question have

been held to represent swords—to which, indeed, they bear some

resemblance—and a theory was in consequence maintained that the West Kirk

had formerly belonged to the Knights Templars. But there is no evidence

whatever to support this, and there can be little question that the

delineations on the stones are crosses in the medieval style of art.

What may originally have been

a projection or transept on the south side of the church, is now used as the

burying-vault of the Johnstons of Sands. It was purchased in the middle of

the last century by the ancestor of the present proprietor from the Browns

of Barhill.

The churchyard of the West

Kirk is still occasionally used for interments, though for the most part

these are confined to the Abbey churchyard. A handsome mausoleum has of

recent years been erected on the west side, though not actually within the

precinct, as the burial-place of Mr Dalgleish of West Grange.

In a field to the north of

the West Kirk, on the farm of the Ashes, is a spring of excellent water,

which bears the name of the Monks’ Well. The name seems to have come down

from Roman Catholic times, as the designation of the fountain-head from

which the monastery was supplied. At least there was then some kind of

reservoir here, as, in an Act of the Scottish Parliament in 1594, confirming

to Alexander Gaw of Maw his possession of certain lands conveyed to him and

his predecessors by the Commendator and Convent of Culross, the field in

question is designated “ The Cisterns.” At the present day, Culross Abbey

derives its supply of water from the Monks’ Well, as did also the mansion of

Valleyfield, till it was cut off in consequence of a dispute between Lady

Baird and the trustees of Sir Robert Preston.

The mansion of Culross Abbey,

which closely adjoins the eastern side of the Abbey churchyard, is said to

have been built out of the materials of the old monastery, and very probably

out of those of which the buildings of the refectory on the south side of

the cloister court were composed. This splendid though uncompleted edifice

was originally erected in 1608 by the first Lord Kinloss, King James’s

favourite counsellor, and Master of the Rolls. I have already given my

reasons for conjecturing that the plan was furnished by the celebrated Inigo

Jones, who was then architect to the Court; and besides the public works in

which he has left so many memorials of himself, had also designed several

mansions for the English nobility. The whole style of architecture is so

superior to anything that could have been produced in Scotland at the

period, that doubts have been propounded as to its being the work at all of

the early part of the seventeenth century. But all the historical and local

evidence that we have goes to show that it really dates from that time; and

the supposition being admitted of the services of an eminent foreign

architect having been called into requisition, the encountering difficulty

vanishes.

Culross Abbey, which thus

succeeded to the title of the old monastery, is an oblong building of three

storeys, flanked by turrets at the east and west extremities of its south

front, which, standing on the crest of the hill, both commands a magnificent

prospect, and, when viewed from below on the water, forms, with the church

and monastery ruins, a most imposing and picturesque group, overshadowing

the town of Culross. The architecture belongs to the Renaissance or Italian

order, such as may be seen in Heriot’s Hospital, Edinburgh, the Banqueting

House, Whitehall, Greenwich Hospital, and other buildings which are

associated with the genius of Inigo Jones. It had originally only been, an

edifice of two storeys, with a tower at each extremity; and the intention

doubtless was to have it completed in the form of a quadrangle, with a court

and grand entrance, most probably on the eastern side. A portion of the west

side of the quadrangle, at right angles to the front or south side, was

actually erected, and now remains to show the plan of the founder. It is

said that Lady Hay, the last surviving niece of Sir Robert Preston, had in

contemplation, besides the restoration of the tower of the church, the

completion of the quadrangle of Culross Abbey.

The architraves of the

windows on the first floor, as well as those on the upper storeys of the

turrets, are marked with the initials L. E. B., D. M. B.— these denoting

respectively Lord Edward Bruce of Kinloss, and his wife Dame Magdalen Bruce,

a daughter of Alexander Clerk of Balbimie. On the east gable are two

superimposed dates, 1608 and 1670. The first refers to the edifice as

originally erected by Lord Kinloss; the second to the third storey, added in

the year last mentioned by Alexander, second Earl of Kincardine.

On one of the old flags which

used to be borne in former times on the occasion of riding the burgh

marches, Culross Abbey was represented as a building of only two storeys. It

had evidently been found too expensive and impracticable an undertaking to

complete it in accordance with the original plan, and accordingly the

makeshift device was employed of increasing the accommodation by the

superimposition of a third storey and attics. These last have now

disappeared, in consequence of the demolition operations of Sir Robert

Preston. It is extremely likely that, in making this addition to the Abbey,

Lord Kincardine availed himself of the services of his kinsman, the

celebrated Sir William Bruce of Kinross, the first architect of his day, and

the designer, both of the greater part of Holyrood Palace as then

reconstructed, and his own splendid mansion of Kinross House on the shores

of Loch Leven.

The entrance to Culross Abbey

is on the north side; but all the principal apartments face the south, and

command splendid views of the Forth and opposite shores. The first floor is

almost entirely occupied by a grand suite of rooms, consisting of dining and

drawing rooms, connected by a noble gallery, after the same manner as is

displayed in Hatfield House, Herts, the seat of Lord Salisbury, which was

designed by Inigo Jones for the first holder of the title—Elizabeth and

James’s celebrated statesman, Sir Robert Cecil. One of those rooms used, in

Lord Dundonald’s time, to be hung with fine Gobelins tapestry, and was known

as the King's Room, from the tradition of King James having been entertained

here on his visit to Scotland in 1617.

Notwithstanding the imposing

appearance of Culross Abbey, the number of apartments that it contains is,

owing to the narrowness of the building and the space taken up with

corridors and state-rooms, not so great as might be imagined. Sir Walter

Scott indeed, on the occasion of his visit, expressed the opinion that it

could not be much more serviceable to Sir Robert Preston than as a

banqueting-house.

By his will Sir Robert’s

trustees were directed to maintain the Abbey in a habitable condition; and

he moreover directed, in somewhat whimsical fashion, that the old

designation of Culross Abbey should be exchanged for the appellation of the

Abbey Elizabeth, in compliment to his deceased partner, Lady Preston, Miss

Elizabeth Brown. This new nomenclature, however, was never adopted except in

one or two legal documents, and is now quite abandoned.

After remaining untenanted,

except by a housekeeper in charge, and almost wholly unfurnished, during a

period of more than thirty years, Culross Abbey was, on the accession of the

Elgin family, held in lease for eight years by Henry Liddell, Esq., of the

Bombay Civil Service, who died here in 1873. It is now occupied by Major

Johnston of the Madras Service, uncle of Laurence Johnston, Esq. of Sands.

The Abbey garden and orchard,

comprising for the most part those belonging to the old convent, stretch

down the slope of the hill towards the public road, and from their

productiveness and fine exposure, still testify to the horticultural skill

and judgment of the monks. They seem to have been laid out in their present

terrace form by Alexander, second Earl of Kincardine, who at least must have

built the pavilion or arbour which occupies the eastern extremity of the

fine upper terrace, and bears the date of 1674. An ancient oak settle placed

within this summer-house has carved upon it, among other indentations, the

words “Jo. Cochrane, 1767,” which were probably cut there in his boyhood by

the Hon. John Cochrane, Deputy-Commissary to the Forces in North Britain,

and younger brother of Archibald, ninth Earl of Dundonald, the unfortunate

projector and speculator. It is probable, however, that the seat is as old

as the pavilion itself.

The whole of the grounds

about the Abbey, though not of great extent, are extremely beautiful, both

in themselves and the splendid views which they command. They used in former

days to be the wonder and pride of the country round. One of the earliest

descriptions of them is contained in the work entitled ‘A Journey through

Scotland,' published in 1723, which, if I mistake not, is the production of

no less distinguished an author than Daniel Defoe. The edition, however,

that I have seen in the British Museum, does not bear his name on the

title-page, and the narrative in question is not included in his ‘Tour

through Great Britain,’ published in 1724. There can at least be no question

as to the date of the work, whatever dubiety we may feel regarding the

author. Having arrived at Korth Queens-ferry, he thus proceeds with the

account of his journey:—

“Continuing my course

westwards by the Frith banks, I arrived in four1 miles at Culross, a most

noble ancient seat of the Bruces, Earls of Kincairn; it stands on an

eminence, as that of Weems does, and hath a noble prospect across the Fri^h

of the county of West Lothian, up the Frith to the mountains above Sterling,

and down below Edinburgh. One cannot imagine a nobler palace. It is built

all of freestone; the front to the south is above two hundred foot, with a

tower three stories high at each comer, and under this front is a terras as

long and as broad as that at Windsor, with a pavilion at each end, and below

the terras run hanging gardens for half a mile down to the Frith. The design

of these gardens was vast; but as they are, you can only judge of what they

were to be and might be. When my Lord Mar was laying out his fine gardens at

Allaway, I am told that when he saw these he thanked God that Culross was

not his, for the expense of keeping it up would ruin him. The house is well

furnished, and in the great staircase are some very good pictures of knights

of the Golden Fleece, cardinals, bishops, abbots, and other eminent men of

the name of Bruce. This branch of the Bruces is sprung from that of

Blairhall, as that of Ailesbury in England is, and all of them from Bruce of

Clackmannan; in this neighbourhood they are a very ancient clan, and very

great in this neighbourhood.

“Culross is also a good

market-town, and there hath been a large old monastery, whose ruins join the

outer court of the Lord Kincaim’s palace. From Culross in six miles I

arrived at the fine village of Alloway, belonging to Erskine, Earl of Mar.”

It is evident from the above

that the journey here described must have been made not later than 1705, the

year in which Alexander, third Earl of Kincardine, died. Subsequently to

that, the Abbey was occupied by Lady Mary Cochrane and her husband. We know

that Defoe visited Scotland two or three years previous to the Union, and

had been despatched thither as a sort of commissioner to aid in bringing

about that event. It is highly probable that he would make a peregrination

through the principal burgh towns of Scotland, and Culross among the rest. I

cling, therefore, strongly to the idea that the author of ‘ Robinson Crusoe

’ actually paid a visit to Culross, and that it is to his pen that we owe

one of the earliest descriptions of the present Abbey and its grounds.

In further reference to this

account—given, as I am inclined to think, by Defoe—it may be observed that

the original design of the Abbey gardens and pleasure-grounds seems to have

been on no less magnificent a scale than that of the mansion itself. The res

angusta domi had in both instances prevented the complete realisation. It

appears from the title-deeds of the Abbey that its site and some of the

ground immediately adjoining were purchased in parcels from different

proprietors. There was thus originally no Culross estate, properly so

called; and even the Earls of Kincardine, as representatives of Sir George

Bruce, notwithstanding the great extent of territory inherited by them,

owned no large amount of property in the immediate vicinity of the family

mansion. The lands which Lady Mary Cochrane succeeded in retaining—in

opposition to the claims of the Black Colonel, who had purchased the? bulk

of the Kincardine estates—were but of limited extent. Her son Charles

Cochrane, however, made some additions to the family property.

Reference has already been

made to Slezer’s ‘ Theatrum Scotisa,’ which, published in 1693, contains

both the earliest pictorial representation of Culross and its Abbey, and in

the letteipress attached to the print the earliest descriptive account. The

author’s name is thus stated on the title-page— “ John Slezer, Captain of

the Artillery Company, and Surveyor of their Majesties Stores and Magazines

in the Kingdom of Scotland.” The views compose a folio volume, and the plate

representing each place is dedicated to the proprietor of the estate. That

of Culross is inscribed, “To the Right Honourable Alexander, Earl of

Kincardine, Lord Bruce,” See. The mansion and grounds of the Abbey bear a

very close resemblance to their appearance at the present day, but the

foreground and the rest of the picture generally are rough and extravagant.

As regards the ruins of the monastery, there is shown a large castle-like

building just in front of the present remains, whilst the arches on the

south side of the cloister court which supported the refectory are also

distinctly manifest. The following description is appended to the print,

translated, it is said, from the Latin of Sir Robert Sibbald:—

“Culrosse hath its name from

Cul, which signifies a bank or back; and Rosse, which was the ancient name

of Fife, because it lies in the western corner of that shire.

“It is situated on a descent

at the side of the river of Forth —its chief commodities being salt and

coals. That which chiefly adorns it is the stately buildings of the Earl of

Kincardin, with the gardens and terrace-walks about it, having a pleasant

prospect to the very mouth of the river Forth. Near unto these buildings are

to be seen the ruins of an ancient monastery.”

As regards the first part of

the above description, it may be observed that there is no evidence whatever

that Fife had ever anciently the designation of Ross, or that it ever

included Culross within its territory. The allegation seems to have arisen

from a fanciful idea regarding the peninsular form of “ The Kingdom,” as

lying between the Firths of Forth and Tay. And Culross was supposed to mark

the back of the peninsula, as Kinross did the head. I shall have something

to say regarding the etymologies of Culross and its district in another

chapter.

At the south-eastern

extremity of the Abbey grounds, just without the eastern side of the garden

of St Mungo’s, and closely adjoining the public road, are the remains of St

Mungo’s Kirk or Chapel, founded by Archbishop Blackadder in 1503, on the

reputed locality of the landing of St Thenew and birth of St Mungo. It is

probable, indeed, that an older cell or chapel marked this site, and the

ground seems in former times to have been part of the patrimony of St

Mungo’s Cathedral in Glasgow. In the ‘ Regis-trum Episcopatus Glasguensis,’

edited by Cosmo Innes for the Maitland Club, it is stated that Robert

Blackadder, the first archbishop of Glasgow, received from James IV., on

24th May 1503, a grant of the lands of Cragrossy, in Strathem, and on 27th

May of same year, from the revenues of these lands* founded and endowed St

Mungo’s Chapel at Culross. The terms of the foundation are as follows: “

Rob-ertus Glasguensis archiepiscopus primus a reditibus terrarum de

Cragrossy quas ecclesiŽ donavit fundavit vnam capellaniam in ecclesia

beatissimi Kentigemi confessoris vbi idem natus erat per archiepiscopum

constructa et edificata prope monasterium de Culros.” The chapel is a

complete ruin, almost level with the ground, with the exception of the north

wall, which resembles a sunk fence in the bank above, and leaves it a matter

of uncertainty whether it was originally built in this form or from the

first stood detached, the intervening space between the wall and declivity

having been subsequently filled up by the gradual descent of earth and

rubbish. Two large beech-trees, certainly not of remote antiquity, flourish

on the summit of this space. There is also the decayed trunk of an ancient

elder-tree which grows near the north-western extremity, where some remains

of the west wall and entrance are still visible. Of the south wall only the

foundations are traceable, and these project into the public road beyond the

present enclosing wall, wliicii was built by Sir Robert Preston. The eastern

extremity of the building formed a three-sided apse—a construction differing

from the ordinary shape of the apse, which is generally semicircular. The

lower part of its east and north-east side is still entire, the latter

exhibiting on the outside a fine front of hewn stone. Traces of windows are

also to be seen here. The length of the chapel from east to west is 54 feet,

and the breadth 20 feet. A wall, still partly remaining, separated the outer

compartment or nave from the interior or chancel, and the raised floor of

flagstones with their rounded edges is still very plainly marked here in

front of the site of the high altar and east window. Traces of sedilia or

seats appear along the north wall, which has a height of from 10 to 12 feet.

About twenty years ago St

Mungo’s Chapel, which had been long abandoned to neglect, and turned into a

receptacle of rubbish, was cleared out, and the outlines of the building,

with its pavement of flagstone, disclosed to view. It was visited shortly

afterwards by a party of members of the Scottish Antiquarian Society,

including Drs Joseph Robertson and Robert Chambers, who were conducted to

the various objects of interest around Culross by the Rev. W. Stephen, who

acted as cicerone. Some excavations made either then or a short time

previously resulted in the discovery of four skeletons— three of grown

persons, and one of a child. These were lying almost immediately under the

pavement, and must have been buried in Protestant times after a considerable

depth of earth had accumulated. Many loose bones were also found among the

rubbish.

On the bank behind the chapel

was St Mungo’s churchyard, enclosed by a wall, of which a small portion

still remains on the east side of the garden attached to the house of St

Mungo’s. Persons only recently deceased remembered seeing tombstones here,

and one of them informed me that on one occasion he had dug up a

coffin-handle. This was about 1816, when Sir Robert Preston was planting

clumps of trees round the fishing cottage, and had given orders that the

mould required for that purpose should be taken from the ground behind St

Mungo's ChapeL On understanding that he was desecrating a churchyard, he

directed that no more earth should be taken from that place. There is reason

to believe that burials took place occasionally here as late as 1750. During

the last century also, St Mungo’s Chapel was used as a place of meeting by

the Freemasons of Culross, who were in the practice of walking thither in

grand procession. The local fraternity was a branch of the great St Mungo's

Lodge of Glasgow, which is said to have been in the habit of sending

representatives on such occasions. The so-called “ St Mungo’s lands ” or

territory in the neighbourhood of the chapel appear to have been regarded as

ecclesiastical property belonging to the see of Glasgow, and thus gave

Archbishop Black-adder an indisputable right to raise on this spot a chapel

in honour of the saint. Certainly we find Queen Mary, in virtue of the

annexation at the Reformation of the ecclesiastical domains to the Crown,

bestowing on the city of Glasgow by royal charter, in 1566, “the lands,

rents, and revenues belonging to the chaplaincies and altarages of St

Mungo.” In 1572 the city made over these to the University of Glasgow, who

appear, however, to haVe afterwards disposed of their right. The chapel and

churchyard seem to have been regarded as the property of the church of

Culross. We have already seen, in Chapter xiv., a claim preferred by the

kirk-session against Mrs Sands, living near St Mungo’s Kirk, for an alleged

encroachment she was making on what was considered to be ecclesiastical or

parochial property.

Next to the Abbey there are

no houses more interesting about Culross than the two old mansions enclosed

within a court at the north-west comer of the Sand Haven, and known as “ the

Colonel’s Close,” from having been occupied in the first half of the last

century by the Black Colonel. Of the two houses, one bears the date 1597 and

the initials G. B., from the great George Bruce, its founder; the other has

the date 1611 and the initials S. G. B., having been erected after Bruce had

been raised to the rank of a knight. Though respectable and substantial in

appearance, such as befitted the residence of a wealthy burgess of the day,

they are by no means remarkable for splendour or beauty of architecture, and

certainly were not designed by Inigo Jones.

It is the interior of these

houses which possesses the chief interest, from the curious painted ceiling

with which the principal apartment in each is adorned. The ceilings are

coved, and the material on which the paintings are executed consists of thin

planking, now very much decayed. The colours are still wonderfully vivid,

though in many places time and damp have obliterated the pictures. In the

older house these consist of a series of allegorical designs, well drawn,

and having attached to each a sentence in black-letter, as a text for the

pictorial sermon, which is either some moral lesson or a representation of

the general instability and uncertainty of human affairs. In the days of

Queen Elizabeth and James these were favourite subjects both for the artist

and poet, and in the latter capacity Edmund Spenser has shown himself facile

princeps as the week-day preacher who presents sacred and philosophic truths

in attractive guise.

These pictures in Sir George

Bruce’s old house, though they cannot lay claim to a high artistic

excellence, are nevertheless of very respectable execution. Among the

designs are “Ulysses and the Sirens,” “ Fortune with her Wheel,” &c. They

are most valuable as specimens of house decoration of the period, and King

James has doubtless frequently sat under and contemplated them on occasion

of his visiting Culross in his expeditions from Dunfermline, and partaking

of the hospitality of Sir George Bruce.

The same house contains a

muniment or strong room, with a vaulted roof and a massive iron door. There

used to be in the room with the painted ceiling a curious folding-down bed,

fixed in the wainscot, showing that our ancestors, though they were fond of

splendidly carved couches, with grand canopies and heavy curtains, were yet

singularly indifferent to comfort in their arrangements for sleeping. Their

ideas of bedroom accommodation seem to have been limited to one state

chamber, whilst the ordinary members of the family contented themselves with

concealed beds, shakedowns, and makeshifts of every kind.

The painted room in the

mansion of 1611 is of a less pretentious character than that in the older

house, the ornaments consisting mainly of geometrical delineations. Each

house is quite distinct from the other, and both are in a woful state of

dilapidation, especially the older mansion of 1597. No one has occupied

either for many years, and the havoc caused by wind, weather, and general

neglect has been very great. It is much to be regretted that something has

not been done to rescue those memorials of the great merchant-prince of

Culross from rapidly approaching destruction.

It is possible enough that

the second house may have been erected by Sir George to accommodate his son,

the younger George Bruce of Camock. It is clear that, being both situated

within the same court, they could only have been intended as residences for

members of the same family, or at least very intimate friends. And there

seems to have been only one garden, common to both mansions.

From references in the burgh

and kirk-session records there can be little doubt of at least the first

Earl of Kincardine, Sir George Bruce’s grandson, having resided in the

tenement in the Sand Haven, though in which of the houses is quite

uncertain. His brother Alexander, second Earl, may also have resided here

for a time, though shortly after 1670, at latest, he had removed to the

Abbey, which had passed from the representatives of the first Lord Kinloss

to those of his younger brother, Sir George Bruce. The Kincardine family

continued to possess the property in the Sand Haven till about 1700, when it

was transferred, with the bulk of their estates, by judicial sale to the

Black Colonel.

Colonel John Erskine of

Camock having found himself prevented from including in his purchase the

mansion and grounds of Culross Abbey, which he had to resign to Lady Mary

Cochrane, took up his abode in the Sand Haven, and from him the tenement

derives its old and most fitting designation of the Colonel’s Close.

Tradition has constantly asserted, though I have been unable to find direct

confirmation of the fact, that the Black Colonel occupied one of the houses

in the court, whilst the other was tenanted by his kinsman the White

Colonel. There was thus a double propriety in the bestowal of the

appellation. Latterly the Colonel’s Close became the property of the

Halkerston family, the members of which, father and son, were successively

town-clerks of Culross. It passed by inheritance from Miss Halkerston, last

resident of the name in Culross, to her relative, the late Captain James

Kerr of East Grange. After his death it was sold by his representatives to

Mr Luke, in the possession of whose family it still remains.

When Captain Kerr succeeded

to the Colonel’s Close, he found it designated in the title-deeds as the

Palace or Great Lodging in the Sand Haven of Culross. Not well versed in

ancient legal phraseology, he at once leapt to the conclusion that the

tenement of which he was now proprietor had in ancient times been a royal

residence. He consequently dubbed it “The Palace,” and its surrounding court

“Palace Yard.” The title was captivating; and to the present hour people not

merely speak of the building as “The Palace,” but assertions have even found

their way into print of its having been an ancient residence of one or more

of the Scottish kings.

Now the whole of this

nomenclature is an absurd blunder, originating in Captain Kerr’s mistake of

identifying with a royal residence the “palatium” or “palace” in the

title-deeds of the Colonel’s Close. This is nothing more than the

appellation which, in law Latin and phraseology, is used to denote any large

or imposing building, more especially any building which is occupied by a

nobleman. Culross Abbey is also designed The Palace or Great Lodging, and

many similar instances from other places in Scotland might be produced. The

term “Colonel’s Close,” as my friend Mr Stephen used to observe, ought still

to be retained, both from having been so long employed, and from its

preserving the memory of an important local if not historical personage. But

when the public has once laid hold of a name, it is almost impossible to get

it altered; and I fear, therefore, that the misnomer of “The Palace” will

continue to mislead and perplex as long as the building itself exists.

The town-house of Culross

deserves some notice, were it for nothing more than the elegant bell-tower

which imparts so picturesque an appearance to the lower part of the town,

and is in its way as characteristic a feature of Culross as her church and

abbey. The building itself dates from the year 1626; but the tower was only

erected in 1783, and provided then with a clock and bell. The town-hall, or

“tolbooth,” as it used to be called, faces the Sand Haven, and is approached

by a double flight of steps leading to the first floor, which contains the

council-chamber and a room formerly known as the “Debtors’ Room,” but now

used as the house of the town-officer. The ground-storey is what used to be

known as the “ Laigh Tolbooth ” or the “ Iron House,” and, as this last grim

title imports, was frequently used as a prison. Another place of confinement

was in the so-called “High Tolbooth,” or garret of the town-house, a dreary

fireless place, contained within the lofty roof of the building, and lighted

through the slates. Here the unfortunate women accused of witchcraft used to

be confined and “ watched.” In front of the town-hall stands a stone

platform, well known in Scottish burghs as the “Tron,” or “Trone,” which, in

Edinburgh and Glasgow, gave a designation to the churches immediately

adjoining. It was the place where commodities were weighed, and the term

belongs properly to the weighing-machine itself, which consisted of a wooden

post supporting two cross horizontal bars with beaked extremities. From the

latter circumstance, the word is derived—i.e., from the old Norse trana, a

beak or crane. It is probably also connected radically with tree and throne.

Previous to the erection of

the present town-hall there had been an older building, the site of which,

in a Scottish Act of Parliament of 1594, is spoken of as the “ground of the

auld tolbuith.” No information can be procured now regarding its situation.

It had doubtless been the prcetorium and prison-house in the days of the

burgh of barony under the abbots.

Just where a narrow passage,

like the neck of a bottle, connects the Back Causeway with the open space

about the Cross, stands a tower-like building containing a fine spiral

staircase, which gives access to two large apartments in the adjoining

tenement, used as workshops by Mr John Harrower, the proprietor. The lower

one of these is a fine well-proportioned room, lined with oak-panelling,

beautifully carved, of which that on the east wall is still in good

preservation, and is, moreover, adorned with some fine inlaid work of a

different material. It bears the date 1633, which, however, is probably only

that of the panelling itself, as indicating the period when, in churchwarden

phrase, the apartment was “beautified” by its owner, some wealthy burgess of

the seventeenth century. His initials, J. A., and A. P. (those, doubtless,

of his wife), are carved with the date on the wainscot, and they also appear

on a beautifully carved door, now detached, though still in Mr Harrower’s

possession, which had belonged to the same apartment. The initials may stand

for John Adam and Alison Primrose; but I can produce little more than

conjecture in support of this statement. There was a family of substantial

burgesses in Culross in the seventeenth century of the name of Adam; and one

of them, who bore the designation of Bailie William Adam, suffered severely

in the days of Charles II. for his Covenanting principles. He may have been

the son of John Adam, who again may have married an Alison Primrose, of a

family of great repute in ancient Culross, from a member of which, Duncan

Primrose by name, as already mentioned, the former lairds of Bumbrae and the

present Rosebery family are descended.

The tenement in question

looks to the south, facing the Cross, and has other apartments besides those

to which access is gained from the turret stair. One of these is on the same

floor, was originally fitted up in the same style, and communicated probably

with the lower wainscoted room. The wall which forms the north boundary of

both is provided with a range of curious arched recesses of hewn stone,

which some have imagined served the purpose of containing book-shelves.

Following this conjecture, it has been surmised that the two apartments in

question formed a library, and had possibly belonged as such to the abbots

of the old monastery. Others have connected them with Bishop Leighton, to

whose diocese Culross belonged. And the appellation of “the Study,” which

the tenement has borne from time immemorial, has been explained as

expressing the purpose for which it was originally employed.

As no positive evidence

whatever exists on the subject, I venture to put forward my own opinion,

that the recesses were nothing more nor less than cupboards or buffets,

which served to contain plate and other articles, as a fitting appendage and

set-off to the general splendour of the apartments. And as regards “ the

Study,” I think the term has been derived not from these rooms, but from a

very curious apartment at the top of the turret stair. This forms externally

a prominent object, projecting as it does slightly from the lower walls of

the tower on which it rests. It is entered from the summit of the spiral

staircase, by a tiny corkscrew stair of its own, which is both of the

narrowest dimensions and closed at the foot by a door. Ascending it, we find

ourselves in a small chamber of about nine feet square and a little over

seven feet in height. It contains a fireplace, and has three small windows

or apertures, looking respectively east, west, and south, commanding views

of the whole town of Culross, and taking in the Forth and its shores as far

as Queensferry on one side, and the Carse of Falkirk on the other. There is

no opening on the north side, doubtless from the view in that quarter being

obstructed by a steep sloping bank. It is exactly such an apartment as

formed the habitation of the sage Herr Teufelsdrockh and overlooked the

whole city of Weissnichtwo. The little staircase leading to it is so narrow,

that in the case of an old woman who lived and died here, it is alleged to

have been necessary to carry her down and place her in her coffin on the

landing-place at the top of the lower stairs. Certainly no place could

embody more completely the idea of a philosopher or wizard’s chamber, cut

off as it is so completely from the outer world, and yet affording such

scope for the study both of nature and mankind, in the distant view of sea

and land, and the near one of the surging tide of humanity which on

market-days gathered round the Cross of Culross.

I conclude, therefore, that

this little chamber, from having been used at one time as a study or

observatory, has given its name to the whole tenement, the walls of which,

it may be remarked, are of an extraordinary thickness—the gable end having a

breadth of nearly four feet. Adjoining the house, as we ascend the hill, is

another tenement, occupied by Mr Harrower himself, which has a remarkable

semicircular projection that may at one time have served as part of a

staircase. What may also have been the doorway at the foot is now converted

into a window, and over it appears the following Greek inscription :—

“God provideth and will

provide; ”

one of those pious and pithy

sayings which our forefathers were so fond of engraving on their dwellings.

The date and author of the inscription are unknown, and the house to which

it belongs, though old, has no other characteristic deserving of special

notice.

The Cross of Culross is an

ancient structure as regards its basement, but the upper part is modem,

having been re-erected in 1819. Four streets converge on the little space

fronting the Cross. A little down from the latter, in the Middle Causeway,

nearly opposite the Dundonald Arms, is a fine old house, which tradition has

connected with Robert Leighton, who as Bishop of Dunblane, the diocese to

which Culross belonged, is said to have resided here on the occasion of his

official visitations. The house is old enough to have existed in the days of

“ the saintly Leighton,” and it contains at least one large and handsome

apartment, finely panelled. But the tradition has been as little verified as

the conjectures regarding the Study.

Facing the town of Culross,

and running parallel to the shore at the distance of about a hundred yards,

is a ridge of rocks, known as the Ailie rocks, behind which the votaries of

Neptune may indulge in.the luxury of a bath without the least risk of being

overlooked by profane gazers. At the western extremity of these rocks is

what is referred to occasionally in the burgh records as the Oxcraig. This

derived its name from the existence there of a species of rude staircase, up

which cattle were driven to be shipped on the farther side for

Borrowstounness. Near this point is a large blue boulder-stone, which,

according to popular tradition, marks the place of sepulture of those who

died of the plague in 1645, and were buried here to prevent the

dissemination of infection by their being interred in the churchyard. Here

also were deposited, it is said, the bodies of any persons who by suicide or

other demerits had rendered themselves unworthy of Christian burial. A

medical man in Culross who lived at the head of the Tanhouse Brae, and had

been discovered hidden in a chimney after having murdered his wife, was

apprehended and lodged in prison, where he ended his life by poison. His

body was interred also near the Blue Rock. Bones and fragments of coffins

have frequently been exhumed and floated ashore from this spot, as I am

credibly assured by persons on whose averments I can place unhesitating

reliance. The Blue Rock has now been somewhat diminished, from portions of

it having been broken down and carried away to make road-metal. At a little

distance on the west side of the harbour is the pier of Culross, which

originally was disconnected from the shore, and could only be reached at

low-water or by wading. A new pier, constructed of stones taken from the

Oxcraig, was erected a good many years ago, and connected with the outer

pier by a wooden jetty.

About two hundred yards up

the Forth, and nearly due west from the extremity of the outer pier, is the

celebrated moat of Sir George Bruce, now merely visible at low-water like a

heap or riclde of stones. It was here that formerly a massive circular

building towered above the surface of the water, as has been already

described in the extract from the “Pennilesse Pigrimage” of the Water Poet,

which presents a very graphic picture of the appearance of the moat and mine

in 1618. Having been blown down in the great storm of the Borrowing Days, at

the time of King James’s death, the works were completely destroyed, and

never again resumed. At present the three concentric walls of hewn stone of

which the building consisted are still distinctly visible, though almost

level with the ground. The tops of piles are also to be seen, and the spaces

between the three walls are firmly packed with blue clay. The distance

between the two outer walls is 3 feet, and between the second and third

walls fully 15. The diameter of the inner wall, which enclosed the shaft of

the pit, is 18 feet, while that of the outer wall from edge to edge is about

60. The landing-place is supposed to have been on the eastern side,

and there are also remains on

the south-west side of what seems to have been a breakwater. The moat

communicated by workings under the sea with a pit on the shore, which is

supposed to have been sunk in the hollow below the house of Castlehill or

Dunimarle. The projection on the sea-shore, formerly an old “bucket-pat,”

has also some claims to be regarded as the site of the pit which the king

descended on his memorable visit, to emerge subsequently by the moat.

Remains of masonry which belonged to this pit, and the draining apparatus

connected with it described by Taylor, are said to have been in existence in

this neighbourhood up to the beginning of the present century. At the

present time nothing regarding its site can be affirmed with certainty.

A very interesting monument

of old Culross—and possibly, after the camps or earthworks, shortly to be

mentioned, the very oldest in the parish—is the Standard Stone, on the

outlying unenclosed portion of Culross Moor, a little to the north of the

farm of Bordie. It consists of a block of freestone, flush with the ground,

and containing two rectangular holes, in which tradition asserts that the

Scottish Standard was fixed on the occasion of the conflict in the middle of

the eleventh century between King Duncan’s army and the invading host of

Danes. The larger hole is about 20 inches long by 12 broad, with a depth of

10 inches; whilst the smaller is 12 inches long by 11 broad, with a depth of

8 inches. Immediately to the south of this, on the farm of Bordie, is the

field know as “Gib’s croft,” in which it is said that Gib, the son of Sweyn,

King of Norway, was killed. The name seems a strange one for a Scandinavian

prince; and it is questionable whether any higher degree of credit can

attach to this tradition regarding the battle of Culross than to the story

of the prowess, at the battle of Luncarty, of the stalwart ploughman and his

sons who turned the tide of battle in favour of the Scots, and became the

ancestors of the Errol family.

A little to the west, and

north of the Standard Stone, in the open and unplanted part of the moor, is

a curious memorial of the persecuting times, called the Pulpit. This is a

stone or rock projecting from the side of a hollow in the moor, facing the

north, and affording a convenient position for an orator or preacher

addressing an audience standing or reclining on the ground below. The stone

is partly hollowed out beneath, so as to present a sort of canopy towards

the north—a circumstance that would not be worthy of mention, except that it

serves to identify the rock and its surroundings. Conventicles are said to

have been held here—a tradition which bears great marks of probability from

the nature of the spot, which is both screened from observation and capable

of accommodating a considerable assemblage. Culross Moor commands an

extensive prospect on all sides, and scouts would be posted at various

points of vantage to give notice of the approach of dragoons. We know,

certainly, that conventicles were held in the neighbourhood of Culross in

the reign of Charles and James II., and no fitter place could be found for

them than hollow places in the moor. The Rev. John Blackadder, the deprived

minister of Troqueer, and one of the Blackadders of Tulliallan, held

meetings, if not here, at least in the immediate neighbourhood. Another

place on the moor that has been connected with conventicles is what is

called the Prayer Brae, on the north-east skirts of the moor, about two

miles from the Pulpit. But though such may really have been the case, no

special locality can be pointed out; and I am strongly inclined to think

that the name itself, which has principally given currency to the assertion,

is a corruption. It is spelt “Prebry” in the burgh records, and seems to be

derived from the Gaelic preas-braigh—i.e., the “thicket height,” or the “

brae covered with wood.” I shall have occasion afterwards to refer to the

matter in the chapter on etymology.

The “Bore” or “boundary”

stone of Culross Moor, already mentioned, will shortly again be referred to

in connection with Tulliallan.

About half a mile to the east

of the Standard Stone, on the estate of Blair Castle, there existed,

previously to 1847, the remains of an ancient British' intrenchment, said to

have been occupied by King Duncan previous to the battle of Culross, and

known by the name of Duncan’s Camp. It was completely obliterated in that

year by Mr Alison, then proprietor of the Blair Estate. Mr Stephen thus

describes its appearance:—

“The site lay about a furlong

or more to the north-west of Blair Castle. There was little even at this

time to mark oat the ground or site. Indeed I believe the remains then shown

were those not of the camp, but of the Prsetorium or general’s quarters.

There was no ditch or trench such as we find on the Castlehill and at the

Moor Dam; there was simply a hollow of some ten or twelve yards in diameter—

the entrance having to appearance been from the north, the ground sloping

gently south. On the south side there was a wall or rampart of earth about

five feet high. The whole ground was overgrown with brushwood and briers.”

Another camp, situated about

the same distance from the Standard Stone in a westerly direction, has been

less ruthlessly treated, and is still tolerably well preserved. It closely

adjoins the east side of the piece of water known as the Moor Dam or

Tulliallan Water, and is said to have been the encamping place of the

Danish, as Duncan’s Camp was of the Scottish host, previous to the battle of

Culross. It bears popularly the name of the “French Knowe,” and has a

diameter of about 60, and a circumference of about 180 yards. The ground has

been partially planted with trees, and a portion of the camp has been

encroached on by the water, but the oval trench and rampart can still be

distinctly discerned.

A third camp in the parish of

Culross is about the most perfect of all—though, being now covered with

trees, and concealed within the recesses of a dense wood, its existence is

almost unknown. It stands on the rising ground called Castlehill, on the

estate of West Grange, about a quarter of a mile to the south-west of

Bogside Station. Its dimensions are nearly the same as those of the camp on

Tulliallan Water, and its contour is more perfectly preserved. A tradition

quoted in the Old Statistical Account of Culross asserts it to have been the

station to which the Danes retreated after the battle of Inverkeithing. This

may bear some remote reference to the last defeat of the Danes, when they

were glad to secure a retreat for themselves in their ships, and permission

to bury their dead in the island of Inchcolme.

Sir Ralph Abercromby, it is

said, when residing at Brucefield on his paternal estate in the

neighbourhood, took great interest in the camp of Castlehill, and used

.frequently of an afternoon, when he had military friends staying with him,

to conduct them thither, to view this specimen of ancient castrame-tation.

It was then free from trees, and commanded a very extensive view. Like all

British or Danish encampments, it is oval in shape, and belongs in no way to

Roman engineers, whose works are characterised by a square outline.

The parish of Tulliallan

contains little that is interesting in an antiquarian point of view, except

the two old churches and the old castle. Of the former, the oldest building

has now almost entirely disappeared, and its site is occupied by the

mausoleum of Lord Keith and his family. This building, with the ancient

little churchyard in which it stands, is situated in a remote comer of

Tulliallan Park, about three-quarters of a mile to the north of the present

castle. The original church, which had existed from Roman Catholic times,

and probably from a period considerably anterior to the Reformation, was, 98

already mentioned, of extremely small dimensions. The parish of Tulliallan

comprehended then merely the barony of that name; but the annexation to it

in the middle of the seventeenth century of a large cantle of territory with

a teeming population, taken from the adjoining parish of Culross, rendered

it necessary to make more extended provision for the exigencies of public

worship. A handsome new church in the Romanesque style of architecture was

accordingly erected in 1675, about a mile to the south of the old church, on

a rising ground overlooking the Forth and town of Kincardine. It was in its

turn abandoned about half a century ago, as being too small to accommodate

the worshippers in it; and an elegant new church, with a handsome tower, was

erected at a little distance below. The church of 1675 was unroofed and

dismantled,' but the walls and belfry remain entire, and it retains the

appearance of a picturesque ruin. The surrounding churchyard is still the

bury-ing-place of the parish, though of late years a new cemetery, erected

by Lady Keith a little to the east of the town on the Torrybum road, has

been gradually coming into favour with the public.

The old castle of Tulliallan

is a picturesque ruin, situated in a park planted with fine old trees, about

a mile to the north of the town of Kincardine. It commands a splendid view

of the Carse of Stirling and rich grounds of Dunmore, with the Campsie

Hills, crested by the Earl’s seat, in the far distance; whilst to the right

of the spectator appears the sinuous crest of the Ochils, in the valley

between which and the Campsies flows the silver Forth, with its many reaches

and finely cultivated banks. At one period the Forth must almost have washed

the walls of the building before the alluvial tract of carse land which now

separates it from the river was reclaimed. In a notice of the parish drawn

up by Mr Bait in 1722, and inserted in Macfarlane’s Geographical

Collections, preserved in MS. in the Advocates’ Library, it is stated that

the Castle of Tulliallan, formerly the seat of the Blackadders, stands close

to the sea, and at that period was altogether in ruins.

The castle must have been a

princely place in its day, befitting the residence of one whose brother was

a munificent Churchman and first Archbishop of Glasgow. It stands on a

square platform, supported by a wall, and surrounded by a moat which is

still perfectly conspicuous. Some very ancient elder-trees overhang the moat

on the west side. The castle consists of a main building three storeys in

height, with a tower or keep at the north-east corner of five storeys. The

lower or ground storey seem to have been chiefly used for kitchen, and

servants’ accommodation, though the roofs of the apartments exhibit a series

of beautifully groined vaulting, resting partly on the walls, partly on

stone pillars, of which one very fine octagon column stands in the centre

of, and supports the roof of, the kitchen. Access to the upper apartments

was gained by two turret staircases at the south-west comer and west side of

the building; whilst a third staircase of a similar description, though not

springing from the ground, led on the east side from the first floor to the

upper chambers of the keep.

With the exception of the

staircase in the centre of the west side—from which, with considerable

difficulty, and even some peril, the first floor may be reached—the stone

steps in the three turrets have almost completely disappeared; and of the

floors, only that of one of the upper apartments remains entire. It is

formed by the vaulted roof of the kitchen; whilst the same vaulting beneath

a second chamber on the first floor has to a great extent fallen in, leaving

only a narrow border along the walls, to be traversed with some little

trouble and risk. These two chambers had evidently been the state apartments

of the castle; and being large and well proportioned, and lighted with one

or two spacious windows, besides smaller openings, all commanding beautiful

and extensive prospects, they impress one with no unfavourable idea of the

domestic accommodation of an old Scottish baron. In the western apartment

are the remains of a finely hewn stone fireplace; and in the eastern, which

is over the kitchen, the remains of a chimney and fireplace can also be

traced. An upper row of chambers, serving as bedrooms, formed a second floor

above these state halls; and still higher above all were the bartizans and

battlements of the castle.

The family of Blacater or

Blackadder, to which the castle and barony of Tulliallan formerly belonged,

was a very rich and powerful one, and an offshoot from the famous clan of

that name in Berwickshire. From a passage in Pitcairn’s ‘Criminal Trials’

(year 1504), it would appear that the estate had come into their hands

through the marriage of a Blackadder with Elizabeth Edmonstoune, the heiress

of Tulliallan. Her son and successor, Sir Patrick Blackadder, appears as one

of the witnesses to the deed of endowment of his brother Robert, the

celebrated Archbishop of Glasgow, in favour of St Mungo’s Chapel, founded by

him at Culross. A successor of Sir Patrick in the Tulliallan estate—but

whether son or other relation, does not appear—was John Blackadder, who,

along with William Lothian, a priest, was beheaded in 1530 for the murder of

James Inglis, abbot of Culross. The family would seem to have decayed after

this, and in the early part of the seventeenth century the property went to

swell the acquisitions of the celebrated Sir George Bruce of Camock. The

following passage from Pitcairn’s ‘ Criminal Trials,’ under date 10th

November 1619, chronicles an outrage that seems to have been perpetrated by

servants or dependants of Sir George,—it is to be hoped without sanction or

connivance on his part, though he undertakes the function of cautioner for

the delinquents:—

“Taking the King's free

liege—Famishing one of the lieges to death in private carcere.—Patrick Cowie

in Kincardin; Johnne Dow, his servand; Johne Andersone, cordiner thair;

Thomas Cowie, querriour thair; and David Miller, salter in Eister Kincardin,—

“Delated of the taking and

keeping of umqle Thomas Davidsoun, hynd and servand to Alexander Leask in

Porter, be the space of fyftene dayis in private carcere within the said

Patrick Coweis hous; and thairfra caiyeing him to the pitt1 of Tullieallane,

quhair, throu want of intertenement, he famisched and deit of hunger and

remanent crymes contenit in the Letteris.

"The justice continewis this

matter to the third day of the next justice-air of the scheriffdome quhair

the de-fenderis dwellis (Clackmannane), or sooner, vpon xv. dayis warning.

And ordanis thame to find new caution, &c.; quha fand Sir George Bruce of

Camock, knyt, personallie present, for thair re-entrie.”

Nothing further is recorded

of this horrible case, and it is probable that further procedure in it was

quashed. A period of nearly one hundred and thirty years was still to elapse

before the abolition of heritable jurisdictions with their inevitable

concomitant abuses.

About half a mile to the

south of the castle is an eminence bearing the name of the Chapel Hill, but

on which no remains of any kind are now visible. It was doubtless in Roman

Catholic times crowned by a small chapel, to serve as a landmark to, and

promote the pious aspirations of, mariners passing up and down the river.

The new castle of Tulliallan,

built by Lord Keith, father of the present proprietrix, Lady W. 6. Osborne

Elphinstone, is situated on the rising ground immediately behind the town of

Kincardine, and nearly a mile east by south of the old castle of the

Blackadders. It is a large and elegant mansion, built on a combination of

the Gothic and Italian styles, and opening on beautiful gardens laid out in

the old French manner, like those of Versailles or Fontainebleau. It

contains a splendid suite of staterooms, the walls of which are adorned by

many fine family portraits. In the summer and autumn they are thronged by a

succession of distinguished guests, the princely hospitalities of Tulliallan

having long been renowned. The adjoining grounds, extending to a great

distance east of the castle, are laid out in beautiful walks formed out of

the old moor of Culross, the termination of which and of the ancient burgh

territory is marked by the celebrated “ Bore ” or boundary stone—a shapeless

lump of sandstone, which hes about a quarter of a mile from the house, near

the kennels, on the left side of the rivulet which comes down from

Tulliallan Water. In the days when the Culross marches formed an annual

pageant, it used to be a favourite jest with the people of Kincardine to

cover the Bore-stone with leeks, in anticipation of the arrival of the

Culross magnates, and as a mild pleasantry in reference to the commodity in

the growth of which their town enjoyed a preeminence.

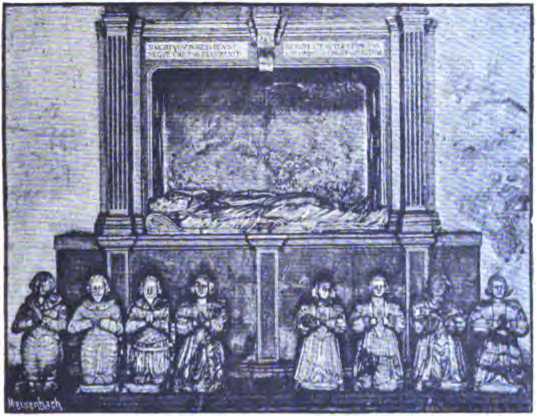

The Tomb of Sir George Bruce in Vault adjoining Abbey Church of Culross.

The Market-place and Cross of Kincardine-on-Forth.

In concluding this notice of

the monuments of Culross and Tulliallan, the Cross of Kincardine, standing

in the open space in the centre of the town behind the Commercial Inn,

should not be forgotten. It consists of an elegant Corinthian pillar, nearly

19 feet in height by 4 in circumference, raised on a' flight of steps, and

seems to have been erected in the seventeenth century by one of the Earls of

Kincardine, as it has the arms of the family carved on the capital. It is

said that both this Cross of Kincardine and the Cross of Perth were cut from

blocks taken from the quarry of Longannet.

In the Debtors’ Room is the

inscription in gold lettere, by a grateful municipality, to Sir George

Preston of Valleyfield, for his benefaction of 2000 marks to the town of

Culross. This circumstance goes to show that there must have been some

subsequent rearrangement of the interior of the tolbooth, as it is extremely

unlikely that such a memorial would have been attached to the wall of a

prison chamber. |