|

TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD NAPIER AND ETTRJCK.

CHAIRMAN OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION

(HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS).

My LORD, I deem it my duty to

communicate to your Lordship, as chairman of the Royal Commission, some

authentic information in respect to my Estates of Tyree and the Ross of

Mull, which have been lately visited by your Lordship and your colleagues.

From documents connected with the

management of the estate, we have a tolerably complete account of the

population, value, and condition of Tyree, from about the middle of the last

century to the present date. It may be of interest to the Commission to know

the leading facts.

Leases of all the principal farms on

the Island for the usual term of nineteen years, or occasionally of

twenty-two years, were granted at various dates between 1753 and 1762. These

Leases of course expired at various corresponding dates between 1772 and

1784. It is towards the end of these Leases, and not at the commencement of

them, that we first have really detailed information. They were granted by

Archibald, third Duke of Argyll, who succeeded in 1743, but whose busy

political life probably prevented him from paying close attention to

agricultural affairs. But towards the close of these Leases the Argyll

estates were in the hands of my grandfather, Field-Marshal John, fifth Duke

of Argyll, who succeeded in 1770, was the first President of the Highland

and Agricultural Society, and who spent the latter part of his life almost

entirely in agricultural pursuits, and especially in the improvement of the

breeds of cattle, which had always been, and still are, one of the principal

articles of Highland produce. So early, however, as the years 1767-68-69, in

three separate papers, we have very full information, evidently collected

with great care, on the statistics of the Island. The total population was

then only 1676, of whom only 69 were employed in handicrafts other than

agricultural. It is remarkable that there is only one column for "tenants

and hinds," showing that many families were on the dividing-line between

regular agricultural tenants and labourers, or cottars with small plots of

land. The total number of both classes is only 236, and a separate class of

cottagers is numbered at only 104 on the whole island. The agricultural

tenants properly so called seem to have been 170. It is still more worthy of

remark that in this return, although there is a careful estimate of all

kinds of agricultural produce, there is no mention of the potato;—cattle,

sheep, and horses,—rye, barley, and oats are the only products noted.

The Leases to which I have referred

as granted between 1753 and 1762, the rental of 1767, and the reports of

1768-69, make two facts quite certain. The first is that many of the farms,

which at a later period became most lamentably subdivided into very small

crofts, were then let to single tenants, several of whom were Highland

gentlemen non-resident on the Island. The second fact proved by these

documents is that even the farms which were then let to "sundry tenants"

were so let to a comparatively small number, who had of course

proportionately larger shares, and these shares, if reckoned at the present

value, would represent small farms quite above the definition of crofts, as

that definition has been adopted by the Commission. That is to say, these

farms, or shares in one farm, would now represent a rent above the £30 line.

Thus, for example, the two farms of Gott and Hianish, now representing a

rental of £163, are specially mentioned in the report of 1769 as having only

four persons in possession. These two farms, if now similarly divided, would

therefore represent a much more substantial class of farms than the crofts

now existing, although these have been much raised and improved within the

last thirty years, by the operations which I shall subsequently explain to

the Commission. The same observation applies to almost all the farms which

were then let under lease, or from year to year, to small tenants.

This shows the delusion which is

commonly entertained, that the system of very small crofts is an old one.

The truth is that in Tyree at least, and in many other places, it is not

nearly one century old. The same conclusion is even more apparent when we

see in this rental of 1767 that almost all the farms which at a long

subsequent date became overrun and cut up into miserably small possessions,

were then not occupied by small tenants at all, but by individual lessees,

or "tacks-men," as they were called in the Highlands. Among the farms then

held in this way I may specify Ballephuil, Balemartine, and Barrapol—all of

them farms which, thirty years ago, had become excessively over peopled and

subdivided, and which, even to this day contain some of the smallest crofts

upon the island.

The opinion of the reporters of 1769

on the minimum size of farm which it would be wise to assign to one tenant

or family is farther indicated by the recommendations they make that certain

farms should be more properly divided. Thus they recommend that the three

farms of Kenovar, Barrapol, and Ballemenoch, which had then seventeen

tenants, should not in future be held by more than ten. It is curious that

these farms are now again held by the same number of crofters which held

them in 1769. But this condition of things is the result of the gradual

process of re-consolidation which has been pursued during the last thirty

years, the same farms having become at one time so subdivided that there

were no less than twenty-nine tenants, instead of only ten as recommended by

the reporters of 1769.

The report of 1769 is farther

interesting as containing conclusive evidence on the waste and misuse of the

land which the small tenants were then making. Much of the soil of Tyree is

almost pure shell sand, which yields a rich and beautiful pasture, full of

clovers of several species; but it is unfit for cropping, and when broken up

is very apt to become blowing sand—not only sterile in itself, but liable to

overrun and render barren large areas of the surrounding land. By this

process two considerable farms have actually been destroyed and lost—the

whole area being now as sterile as a snow-drift. The report of 1769 shows

that the very poor and very ignorant tenants and subtenants who were then in

possession were cropping this light sandy land to an injurious and dangerous

degree, and recommended the erection of strong dividing dykes, with

conditions prohibiting the practice.

Another signal example of the

contrast between crofts or small farms as recommended by the skilled and

intelligent reporters of 1769 and the miserable; possessions which

subsequently arose from the improvident habits of subdivision, is furnished

by the example of the two farms of Balephuil and Balemartine. These two

farms are mentioned as having been "formerly" held by one tenant, who was at

that time the factor or chamberlain: and the reporters recommend that if

they are to be divided the total number of divisions should not exceed ten.

Yet on these two farms the reckless process of subdivision went on

subsequently to such an extent that there were no less than sixty-nine

crofters—all of the poorest class. At this moment there are still thirty,

which is exactly three times, the number which the reporters of 1760 could

recommend as enough to live comfortably and profitably on the land.

The next document of importance is

dated seven years later—in 1776; and it is very instructive. It is a draft

of "Articles, Conditions, and Regulations to be observed by the Tacksrnen

who have obtained leases of Farms on the Island of Tyree." It appears from

this paper that in Tyree, as elsewhere in the Highlands, the small tenants

were still holding and cultivating in what was called "runrig," and is still

called in Ireland "rundale," that is to say, under a system of management

which is absolutely incompatible with the very first germs of agricultural

improvement. The possession of each tenant was divided into innumerable

separate little plots of land—none of which remained in his possession for

more than a year or a couple of years, the various plots and patches being

re-divided each year by lot. It was of course the interest and duty of

proprietors to put an end to this system, and by no other agency than

proprietary power and right could it have been abolished. Like all ancient

and barbarous customs it was clung to most tenaciously, although after a

little experience of separate possessions the tenants generally soon

acknowledged the superiority of the new system. Accordingly, it was laid

down as the first and foremost of the new conditions that "runrig"

possession of "corn farms" (arable land) were to be entirely abolished, and

every tenant was to occupy (by himself or servants, without subletting) a

distinct separate possession, more or less extensive, according to his

ability, not below the extent of a four mail land.

This last condition is especially

interesting, as showing again, in a definite form, the opinion then

entertained by the proprietor and his advisers as to the minimum size of

farm which would constitute a comfortable living for a tenant. A "mail land"

was a division which included four of the smaller divisions called a "soum,"

and each "soum" represented the grass of one cow, or of two two-year-old

cattle, or of five sheep, so that each tenant was to have at least a farm

capable of holding 16 cows, or 32 young cattle, or 80 sheep. This is,

indeed, a very comfortable little farm, and would generally be rented now at

more than £30. In other words, they would not be crofts at all, but would

belong to the class of small farms.

Another important fact we learn from

this paper is that the selection of persons to fill the new farms or crofts

was not made arbitrarily by any favouritism, but was settled by public roup.

No right of possession either by custom or otherwise was claimed or thought

of by any tenant or sub-tenant on the island. They had generally held by

Lease for definite periods, or as sub-tenants at will under the individual

Tacksman. The new arrangement was made when the Leases came to an end, and

when the proprietor by virtue of the expiry of these Leases came again into

full possession of the land. The small tenants were taken bound to build the

houses and the march fences between each other at their own expense; and as

community of possession could not be abolished upon the common pasture land,

as it was now abolished on the arable land, the tenants were taken bound to

submit to and observe any regulations laid down by the factor for the "souming,"

or amount of stock to which each tenant should be limited. The prohibition

of ploughing up the sandy land, or links, completed the principal

regulations which were laid down, and which sufficiently indicate both the

wretched husbandry of the preceding times, and the real source from which

all improvement came in the times which were to follow.

Two years later, in 1778, a farther

report, going in detail into each farm, emphasises the same principles of

improvement,—remarks on the poor and scanty kinds of grain which were raised

in the Island, points out that the ignorance of the people was due

principally to their total isolation and want of communication with the

mainland, and recommends the establishment of regular sailing packet-boats.

Notes upon this report, in the Duke's handwriting, make it evident that he

had gone minutely into it; and that, from this date to the end of the

century, that is, during the following two-and-twenty years, a great deal

had been done in dividing several farms into good-sized separate

possessions, and in clearing them of a scattered surplus population, which

was transplanted where their labour would be available for agriculture and

for fishing. The Duke had then also tried to encourage the fisheries, by

keeping men in his own employment; but this was a failure, as the men, being

independent of success, were idle and drunken. The reporter, wishing to go

out in a boat to try the fishing, had found the Duke's fishermen so drunk

that they could not take him. I mention this circumstance, which occurred

now more than a century ago, because it enables me to record the fact of a

signal change for the better in the habits of the people. The fishermen of

Tyree are now as sober as they are industrious. Indeed, I question whether

there is any part of the Highlands where drunkenness is less common—a result

to which I hope and believe that I have contributed something in never

having granted a site for any public-house to be established on the Island.

In the Leases given by the Duke, from

1776 onwards, I find that the erection of houses, and of march fences in the

form of dikes, was made, an obligation on the tenants themselves, and that

this kind of improvement was therefore done under specific agreement that it

was to be held as done for valuable consideration received in the Lease, and

in the moderate rent offered and accepted. These Leases are farther

remarkable for the proof they afford, if, indeed, any proof were needed,

that it was solely by the influence and authority of the proprietor that

various old barbarous habits of cultivation, or rather of waste, were

abolished and abandoned, such as burning of the surface, and others, the

very names of which are now obsolete and forgotten.

This appears to be the proper place

to notice the rise of the trade in kelp, manufactured by the burning of

drift and cut seaweed—a product which began to be valuable about the middle

of the last century. It is not, however, till we come to the report of 1778

that any specific mention is made of the kelp trade. But in that report the

quantity of kelp which could be produced on the shores of several farms, on

an average, is mentioned in the report on these farms. The amount, however,

mentioned is very inconsiderable, and it is evident that the returns from

kelp had not at that time become any large part of the value of the Island.

But towards the close of the century, and on to 1810-12, the produce of the

Island in kelp very often exceeded the whole agricultural rental; and the

system which seems to have been adopted as regards the price paid to the

tenants of the farms on the shores of which the kelp was produced, is

perhaps the most important fact which helps to explain the subsequent

economic condition of the people. So large a share in the price of the kelp

seems to have been allowed to the tenants, and to have been accepted from

them to account of their rents, that very often they had no rent at all to

pay for their purely agricultural possessions. In the years from 1800 to

1808, for example, the island seems to have produced somewhere from 200 to

300 tons of kelp, which in the later part of this period became worth from

£10 to £12 per ton. After deducting all expenses, this quantity yielded a

sum nearly equal, or sometimes exceeding, the whole agricultural rental; and

in the estate accounts the factor is found discharging himself of that

rental altogether by setting off against it the return of kelp. I have

letters and papers written by my grandfather, in which he points out that

under these conditions the tenants had their land practically rent free, and

concludes from this circumstance, and from his knowledge of the stock and

crop raised in the Island, that the rental must have been, even then, far

below the real value of the land. The indisputable facts upon which he

founded this conclusion were mainly these—that whereas the whole rental of

the Island was then about £1000, there were not less than 13,000 acres of

fertile land out of which that rental could be met, without taking into

account at all the very large sum made by the tenants out of their share of

the kelp. The Island was even then known to produce 1000 boils of barley.

This, together with the kelp, would produce far more than the whole rent. "I

allow," said the Duke, in explaining his calculation, "all the oats, all the

potatoes, all the lint, all the sheep, all the milk, butter, cheese,

poultry, eggs, fish, &c., which in other countries are sold to contribute

rent—I allow all these to go for the support of the tenants, because I wish

them to live plentifully and happily."

It is quite needless to point out the

natural and inevitable consequence of such a condition of things. If it were

possible by the artificial cheapening of commodities to establish among any

people a higher standard of living than that to which they were accustomed,

this benevolence might have been successful. But it is not possible. The

establishment of higher standards of living must come by exertion, and by

thrift,—not by gratuitous benefits which dispense with both. Accordingly

this unnatural lowering of rent, by allowing a wholly extraneous produce to

stand in lieu of it,—and all this consequent temporary abundance had the

reverse effect. It did not produce wealth or comfort, but, on the contrary,

only poverty and indigence. It removed every check upon the law under which

population tends to press upon the limits of subsistence. It supplied an

insuperable temptation and encouragement to an improvident multiplication of

the people, to wasteful habits, and to a systematic breach of the conditions

against the reckless subdivision of farms or crofts. When it is remembered

further that the period I have now reviewed was contemporary with the

introduction and spread of the potato, and of inoculation, which put an end

to the old ravages of smallpox, we can readily understand the results which

followed.

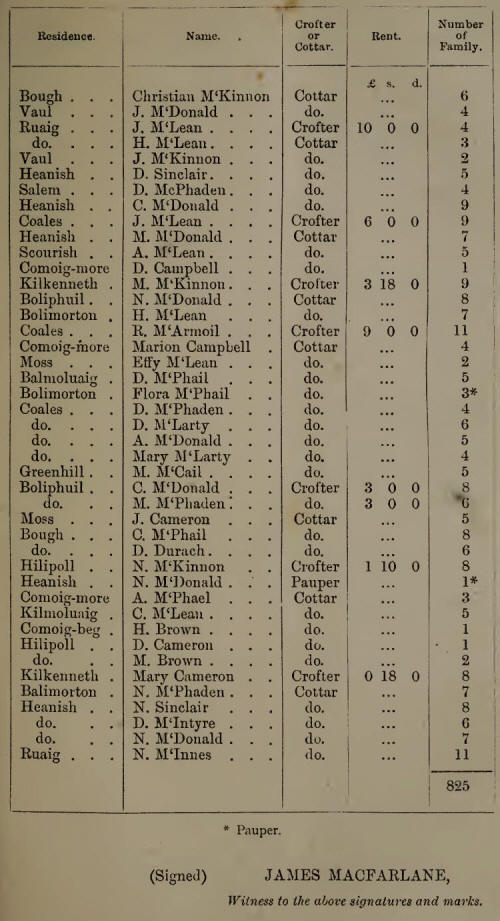

Accordingly, we find that the

population of the Island, which so late as 1769 had only amounted to 1676

persons, had in 1802 multiplied to a total of 2776. And the same rate of

multiplication was then going on, and was even rising. The parish registers

have been lost up to 1784. But from that year (inclusive) to the end of the

century, we have a list of the yearly births and of the yearly marriages.

The births in the year 1800 were 116, and the marriages were 41. The last is

a far higher rate of marriages to population than now prevails in the most

thriving cities of the country.

It is in a paper of a little later

date—1802—that we have by far the most able and detailed account of the

agriculture of Tyree, and the most vivid picture of the condition to which

by over-population and subdivision the inhabitants were then reduced. This

Report was drawn up by Mr. Maxwell of Aros—a gentleman whose name was widely

known in the first quarter of the present century as my grandfather's

chamberlain on his estates in Mull and Morvern. It was in his house at Aros

that the many distinguished men in literature and in science who came to

visit Staffa and Iona were hospitably received, and were forwarded on the

journey by which alone at that time those Islands could be approached. His

name is linked with a distinguished man and a distinguished family of our

own time—for Mr. Maxwell became the grandfather of the late Dr. Norman

Macleod, through a daughter whose most beautiful and venerable old age of

nearly one hundred years came to its close but a very short time ago. Mr.

Maxwell's Report to my grandfather in 1802 is a model of what may be called

the scientific treatment of such a subject. He shows that there were then

319 tenants of crofts so small that even under better management they were

inadequate to support a family, whilst under the wretched husbandry which

actually prevailed, they were, of course, still more incapable of doing so.

Many of these crofts barely fed two cows, and an extravagant number of

horses reduced the grazing of these cows almost to the starvation point. One

consequence was that the cows did not produce a calf above once in two or

three years, so that they afforded little profit to the tenants "either in

the way of milk or rearing." But this was not all. Preying upon the tenants

of these small possessions there was besides a whole host of cottars who had

no land of their own, —but who, nevertheless, kept cattle and horses for the

collection and transport of sea-weed, and these cattle and horses being

wholly unrestrained by adequate fences, impoverished still more the common

pasture, and must have trespassed continually even on the crofts themselves.

Very naturally, Mr. Maxwell denounced this condition of things as a

"shameful abuse and oppression upon the tenants, hampered as they themselves

were for want of room." Everything else was of a piece. The barley raised

upon the Island is described as "of the meanest quality:" and it appears

from many passages of the correspondence of this time, that it had been

largely used for illicit distillation. From a careful calculation of the

maximum produce of the crofts, consisting of "one mail land," it is shown

that, allowing only about one-sixth part for rent, the remaining five-sixths

could not support the tenants "except in penury." Mr. Maxwell pointed out

the great difficulties in the way of remedying a state of things so

desperate,—difficulties increased tenfold by the mental condition of the

people. "It is proper," he says, "to remark to your Grace that the general

poverty of the tenants, in consequence of the Practice of breaking down

their possessions into inconsiderable shares—their stubborn attachment to

old customs— the idleness of their habits—and their total ignorance of any

better system of management, oppose very arduous obstacles to the

improvement of the Island." Not that Mr. Maxwell had any doubt of its great

natural fertility, for he suggests among other things that some regularly

bred and practical farmer should be introduced into the Island to show the

people that the soil on which they were only saved from starving by the

extraneous resources of the kelp trade was "capable of producing returns of

which they had no conception." He pointed out, however, that even this

measure would be necessarily slow in its operation, since "the general

poverty of their circumstances conspired with the general idleness of their

habits and the backwardness of their knowledge," to render hopeless the

possibility of such examples being followed. Mr. Maxwell had no doubt of the

necessity of at least one remedy. He declared his opinion that not less than

one thousand people should be assisted to emigrate to America or Canada. The

people themselves had come to wish it. My grandfather, though averse, had

also come to entertain the proposal. But just at that time one of these

panics had arisen about the evils of emigration and depopulation which seem

to he of periodical recurrence. A committee of the Highland and Agricultural

Society, of which my grandfather was president, had sat upon the subject.

They had treated emigration as a national calamity. They had recommended

every conceivable expedient—each one more absurd than another—for preventing

the people from seeking a land of greater abundance. They had advised the

making of roads by Government—the making of canals by Government—the

establishment of Government bounties upon fishing —bounties upon building

villages—bounties upon crofting - bounties upon building boats - bounties

upon anything and everything that could be thought of as bribes and baits to

induce the swarming multitudes not to swarm, and not to establish new hives.

Under the pressure of this panic, Parliament had been induced to interpose

obstacles on emigration by artificial regulations and restraints. My

grand-father also was under pressure from different directions. In order to

constitute proper crofts it was absolutely necessary to dispossess many

families who had squatted on minute subdivisions. He desired also to give

land to many fishermen. And last, perhaps not least, the military instincts

of the old Field-Marshal made him desirous of accommodating some discharged

soldiers of the "Fencible Regiments" which had been raised under him. For

all these three classes of men, therefore, he desired to constitute crofts

on the plan which he had long conternplated—crofts, if possible, of not less

than "four mail lands."

It seems to have been to meet this

condition of things that my grandfather John, the fifth Duke, agreed to

divide some farms, hitherto let to single tenants; and in 1803 Balemartine

was let to thirty-eight crofters, whilst no less than fifty-six applicants

are mentioned in one of his notes as anxious to be provided for out of other

farms in a similar manner. These crofts, however, seem to have been of a

tolerable size, from eight to ten acres.

It does not appear that my

grandfather had present to his mind the danger of the course he was

pursuing. He had indeed some misgivings. But nobody at that time could

foresee the scientific discoveries, and the changes in tariffs, &c., which

within a few years were to put an end to the large profits derived by the

tenantry, as well as by proprietors, from the manufacture of kelp; nor did

he, perhaps, sufficiently consider that even if that manufacture had

continued on the same scale, the increase of population, if not somehow

checked, would soon overtake its supplies: and that unless his successors

enforced strictly the prohibitions against subdivision, the inevitable

result would be a vast semi-pauper population.

These dates are, however, interesting and important, as

showing how unfounded are the impressions now common among the people as to

the antiquity of their occupation of the small crofts which many of them

still possess. In Tyree the great majority of these crofts were not more

than about forty years old when the crash of the potato famine came in 1846.

And so far from the possessions held by the tenants having long belonged to

themselves or their "ancestors," these possessions were either given to them

by the special favour of the proprietor at a very recent period, or were

still later acquired by irregular sub- divisions against the rules and

regulations of the estate.

All these causes of impoverishment were doubtless

aggravated by the death of my grandfather in 1806, and the succession of

George, the sixth Duke of Argyll, during whose life of thirty-three years

the restraining and regulating power of a landlord was comparatively in

abeyance. Nothing but this power, steadily exercised, could have checked the

ruinous tendency towards subdivision, or supplied the knowledge and the

foresight which are invariably wanting to a population living under such

conditions.

The result was what might have been expected. Mr. Maxwell

of Ares lived to see that result in melancholy operation. Nineteen years

after his report to my grandfather, he was again called upon to report to

his successor on the condition of Tyree. In 1822 be was obliged to report

that, as a "natural consequence" of the system adopted, "the families have

now multiplied to such an unmanageable degree that the whole produce of the

Island is hardly sufficient for their maintenance, and the crowded

population on its surface exhibit in many instances cases of individual

wretchedness and misery that perhaps are not to be found in any part of

Scotland." The farms which had long been possessed by small tenants were now

found to contain 2869 souls, whilst the five farms which had been broken up

into small lots now contained no less than 1080. The potato disease was as

yet unknown, but the ordinary vicissitudes of the seasons are always at hand

to punish glaring departures from sound economic laws. 1821 wits a year of

extraordinary drought, and on the light sandy soils of Tyree the crops were

almost a total failure. The cattle were almost starved, and were so lean as

to be unsaleable. Kelp was again the only resource. There was an

extraordinary supply of it in 1821. By this means and by wholesale

remissions of rent, the crisis was tided over; but no permanent remedy was

applied, and so matters went on again in the old rut. In the course of

forty-three years from my grandfather's subdivision of the farms,—with

little or no increase of agricultural production, and an immense deficit in

a manufacturing resource,—the population had nearly doubled, so that when

the crash of the potato failure came in 1846 it exceeded 5000 souls, whilst

the small crofts had been so much farther subdivided as to number 380, of

whom all but a mere fraction were below £10 rent, and the great majority

(218) were even below £5. Of these last, again, a very large number were as

low as 30s. and £3. There were, besides, a large population of cottars who

were without any land, employed, in so far as they worked at all, in fishing

and very casual labour.

When the potato famine came in 1846, the destitution of

the people was as severe as under such circumstances it could not fail to

be. Not only was there great distress, but there was danger of actual

starvation. My father, John, seventh Duke of Argyll, was then in possession

of the estate; but as he was in feeble health, I was obliged to take a

principal share in devising measures of relief, and as he died in the spring

of the following year, 1847, I consider myself practically responsible for

the management of the estate from the date of the potato failure in 1846. A

large sum was spent in providing meal for the people, and another large sum

in assisting as many as were willing to emigrate to Canada. I have not

beside me at this moment any note of the exact number who went to Canada,

but in the course of four years it exceeded a thousand souls. The whole of

this was a purely voluntary emigration, for a great portion of which I paid

the whole cost myself, whilst assisting in the expenses of the remainder. In

1851 the people were still eager to go, and I print in an Appendix to this

paper the remarkable petition which they sent to me and to the Government

seeking further aid towards emigration. I saw, however, that emigration was

not the only remedy which the condition of the Island required. Active steps

were taken to give employment to the people in draining, in the making of

roads, and in various other agricultural improvements. As the rents of the

crofters could not be generally collected, these outlays had to be provided

for out of other resources; in fact, I was myself compelled to borrow a

large sum; and it is needless to point out that this outlay could not have

been provided for at all had the Island belonged to a proprietor depending

wholly on its own rental, and still less had it been divided into smaller

estates.

Nor did this condition of affairs pass off immediately, or

even soon. During the four years from 1846 to 1850 the sum spent on

improvements in Tyree and the: Ross of Mull was £7,919, or, including

incidental expenses, upwards of £8,000, of which the greater part —about

£6,373—was in drainage alone. This was in addition to the sums spent in

emigration and in the distribution of meal, which could not be repaid either

in money or money's worth. In the report of Sir John M'Neill to the Board of

Supervision on the Condition of the Highlands and Islands in 1851, he

states, from documents then before him, that during the previous four years

there had been expended on wages and gratuities to the inhabitants a sum

exceeding the whole revenue derived from the property by £4,680, which

amount, as well as the cost of management, must have been derived from other

sources. This is quite true, and is, indeed, a good deal understated. During

those years no part of the income derivable from the Island was spent out of

it, and the outlays it needed constituted a heavy drain on other resources.

In the year 1851 the reduction of the population to 3706,

and the return of some favourable seasons, brought about the beginning of a

better condition of things. But my outlays on improvements, for the sake of

employing the people, and for the sake of increasing the produce of the

Island, continued to be heavy. In the seven years from the famine to 1851

these outlays exceeded £10,160, of which the greater part was in drainage.

I had by this time begun to find that the outlays on

emigration had produced one bad effect—namely this, that the people

conceived it to be a boon not to themselves, but only to the proprietor, and

were disposed to rely upon him entirely in regard to it. I therefore ceased

altogether to offer it to them, leaving it entirely to their own suggestion,

although I was always willing to help when occasion required. Sir John

M'NeilI, in his Report of 1851, mentions that in that year there were 900

persons then anxious to go to join their friends in Canada, from whom good

accounts had been received. This number would very nearly have reduced the

population to the figure at which it stands at present, that figure being,

according to the census of 1881, 2700. It may be roughly assumed, therefore,

that the 900 persons who were anxious to go in 1851 represent those who have

actually gone from one time to another during the last thirty years.

I may now at once explain to the Commission the principle

on which I determined to proceed in the improvement of the Island from the

moment when the first extreme pressure of the years of actual destitution

had passed away. I was satisfied that the population was excessive, arising

from the causes to which I have referred, and from the ruinous habits of

subdivision which had been inseparable from the improvidence which is at

once the cause and consequence of increasing poverty and of a low standard

of living. Sir John M'Neill points out that the whole rental of the Island,

if divided among its population even at the reduced figure at which it stood

in 1851, would not have afforded crofts of a higher value than

which is

much too small for the subsistence of a family.

But although I was convinced of the necessity of a further

reduction in the numbers of the people, and especially of a consolidation of

the crofts so that they should be of a comfortable size, I had an

insuperable objection to taking any sudden step in that direction such as

might be harsh towards the people. I thought it my duty to remember that the

improvidence of their fathers had been at least seconded, or left unchecked,

by any active measures, or by the enforcement of any rules by my own

predecessors who had been in possession of the estate. I regarded myself,

therefore, as representing those who had some share in the responsibility,

although that responsibility was one of omission and not of commission.

On the other hand, it seemed to me that if, for the

future, rules against subdivision were steadily enforced, and if every

opportunity were as steadily taken to make good use of the vacancies in

crofts which might arise by death, by migration, and by emigration, some

progress would be made by a slow but sure process towards a better condition

of things.

Accordingly, I determined not only to avoid anything like

what has been called a "clearance," but, as a rule, not even to allow any

individual evictions or dispossession of the existing crofters, except for

the one cause of insolvency or non-payment of rent. During the thirty years

which have elapsed between 1853 and 1883, there has been only one solitary

case of the eviction of a crofter by Warrant of the Sheriff, in the whole

Island of Tyree ; and this was an eviction made, not in the interest of the

Proprietor, but in the interest of the neighbouring tenants. [Certain

statements to the contrary on subject recently made in the press are as

false as those made in the same quarter in respect to the occupation of

Widows. it is possible, however, that these statements may be due to the

ignorance which confounds between forcible evictions and the ordinary

"Summonses of Removal," which are issued as a matter of course on all

changes of tenancy.]

Further, I determined that in all cases when a croft

became vacant by any of the causes just mentioned, it should, if possible,

not be reoccupied by itself, even when a higher rent could be got by doing

so, but should be added to some adjacent croft, if any one of the neighbours

was capable of managing arid stocking the consolidated possessions.

On the other hand, I never contemplated, and could never

have approved of cutting up and dividing among crofters the few farms on the

island which in 1846 were still held by individual tenants, and all of which

had been so held for a long period of time. Most of them had never been

possessed by the class of crofters. None of the crofters had capital or

knowledge fitting them at that time for the profitable occupation of farms

of even a moderate size. The farms held by single tenants were the only

farms which afforded any immediate prospect of a great increase of

production—they were good customers for the cattle of the crofters—and they

were the only field upon which the benefits of good farming could be held up

to the example and imitation of the poorer people. Tyree is almost singular

among the Hebrides in this—that there are no waste lands, properly so

called, upon it. There are no moors—no mosses to be reclaimed. The old

mosses have been long exhausted and cut away to the very bones of rock and

gravel.

I wish the Commission, therefore, distinctly to

understand, that with one single exception which I shall refer to presently,

what may be called the large farms in Tyree have not been gained at the

expense of the crofters. On the contrary, in Tyree the process so much

complained of elsewhere has been reversed. The crofters now possess farms

which up to a late date were held by single "Tacksmen;" whilst in one case

only have individual tenants, now occupying the larger farms, replaced the

regular crofting population as it stood in 1846. A few families who belonged

to what may be called the class of squatters, and who had settled upon one

or two of these farms, occupying upon part of them very small bits of land,

were among the number of those who emigrated, or were subsequently moved.

But with the one exception above-mentioned, the only other example of any

considerable removal of crofters is a case in which both the cause and the

consequences were entirely different. It arose from insolvency and

non-payment of rent. And in this case the farm was not let to a new tenant,

but was divided between four of the existing crofting tenants, in respect to

whom there was good hope that with larger and more comfortable possessions

they would be able to prosper. This hope has not been disappointed. The farm

I refer to is the farm of Maunal—formerly subdivided into twenty-three

crofts, or rather fragments of crofts, rented at from to 30s. each. This

farm is now held by three tenants who have risen from among the rest, of

whom two pay rents which place them above the crofting line (£30), whilst

the other (a widow) has a croft not much below it (£24, 14s. 6d.).

The one exceptional case of a farm now held by a single

tenant which in 1847 was held by crofters, is no less remarkable as an

illustration of the varieties of circumstance which must determine such

results. It is the farm of Hillipol, which had come to be subdivided into

twenty crofts so small that one quarter of the whole number were under £2

value, six others were under value, and none exceeded £5 value. In 1847,

however, three of them had become vacant and were in my own hands. This was

one of the farms on which I determined to expend a large sum in drainage. It

was good strong land, but in miserable condition from wet and from the most

wretched cultivation. During four years nearly £1000 had been spent in

draining and fencing. The tenants had been generally in arrear even at the

old rents, and none of them could pay the interest on the outlay, which the

land under better management could more than well afford. They naturally

fell further into arrear, and were obviously incapable of managing and

stocking the farm in its improved condition. The result was unavoidable that

during the years of emigration and of insolvency affecting this very poor

class of crofts, the tenants of Hillipol were amongst the number of those

who disappeared. In 1853 the greater part of the farm was in my own hands.

It has since been let as one farm, and it is a signal evidence of the

immense increase of production which arises on land well managed, and held

by men having sufficient capital, that the rental of this farm has risen

from £62 in 1847 to £376 in 1883,—this increase, however, having arisen not

without large and renewed outlay on draining and fencing.

The case of Mannal is, I think, a typical case of the

process to which we can alone look for the improvement and successful

establishment of a class of small farmers. Those who eked out a living

between bad farming and bad fishing,—and occasional labour not much higher

in quality than the farming or the fishing,—will generally thrive best by

pursuing one or other of these occupations by itself, whilst those who are

devoted to agriculture can only thrive upon possessions of a certain minimum

size. In Tyree generally this result could only be attained upon the

principles before explained by a very slow and gradual process. But by that

process steadily pursued it has been attained at least to a very

considerable extent; and I shall now give to the Commission the figures

which indicate that result.

In 1846 there were no less than 218 crofts, or bits of

crofts, below £5 value. In 1880-81 there were only 34 left of this very poor

class. Between £5 and £10 value there were in the same year 102, whereas

there are now only 68. On the other hand, the next class, between £10 and

£20 value, has been increased and recruited from 38 to 72, whilst the still

more comfortable class, between £20 and £50, has been raised in number from

5 to 26, and of these no inconsiderable proportion has been lifted

altogether above the crofter limit of 30, and the tenants are now ranked

among the farmers.

Although I am aware that the special subject of the

Commission over which your Lordship presides is the crofter class, it is

impossible to consider fully the position occupied by that class (below £30)

in any particular locality such as Tyree without taking into account the

number of small farms above that line which have been created out of the

consolidation of crofts, and are now held by precisely the same class of

men, but who have risen by the opportunities which I have thus afforded to

them. In connection with this most important part of the objects at which I

have aimed I may mention a particular case. A good many years ago advantage

was taken of various vacancies to constitute one little farm above the

crofting line on the old single farm of Cornaigbeg. In order to complete

this possession, and to square off its little fields, it became desirable to

get rid of one small croft which stood in the way. It was held by a widow. I

desired my factor to offer to her another croft which was vacant, which was

quite as good, and was not a hundred yards off. But he had to report to me

that nothing could induce the worthy old woman to move, and asked whether I

wished him to apply for a summons of removal. I replied that I was most

unwilling to take any forcible steps in the matter; but I enclosed a

personal letter to the widow explaining the reasons which made me wish that

she should exchange crofts, and assuring her that I did not wish her to be

in any way injured by the change. This letter was at once successful, and

the widow removed to the croft offered her in exchange. A very few years

later a much larger farm than that from which she moved became vacant, and

it was advertised to be let. When the offers came in, I was much surprised

to find that my old friend the widow, who had been so reluctant to move from

a small croft, was much the most eligible offerer for the vacant farm, and

she is now, I hope, comfortably installed in a possession which is not only

far above the crofting line, but is relatively even a large farm. I do not

know any circumstance which has ever arisen in my management of Tyree which

gave me more pleasure. Last year I called upon her in her new home, in which

I hope she may be as successful as I wish her to be.

Another case I may mention is one which has occurred on

the farm of Hianish. This farm, when I succeeded to the estate, was

subdivided into sixteen very poor crofts, most of them below £3 rent, and

only one as high as £6. But this last was held by a crofter, Niel M'Kinnon,

who had given an admirable education to a fine family of sons, most of whom

had entered the commercial marine, and one of whom became highly

distinguished as captain of one of the fastest "Clipper" ships trading to

China. The father died leaving a widow who was justly proud of her sons, and

the late Duchess and I were almost as proud of her satisfaction in them. In

the course of years she lost them all but I have had the great pleasure of

enlarging her croft steadily as vacancies occurred around her, and of

associating with her in the possession her daughter and her son-in-law, who

were alone left to carry on the succession of a most meritorious family. I

am happy to say that my old friend Widow M'Kinnon is still alive, and in

possession of a little farm of £50 rental, where I often visit her, and

where I trust she and her descendants may continue to be found for many and

many a long day.

Another excellent example is the case of the farm of

Scarnish. In 1847 it had come to be subdivided between fifteen tenants—most

of them with possessions of the very smallest class—ranging from 20s. to £3

rent. But one of the tenants afforded a nucleus for consolidation, as he

already possessed four of the subdivisions, and paid £6, 16s. of rent. But

even this small advantage, with a corresponding share of intelligence and of

industry, gave to this crofter a start, of which he has known how to take

advantage, whilst it has been a pleasure and a satisfaction to me to reward

his exertions. As others fell back in the race, he has pressed forward. It

has been a regular case—not of the substitution of a stranger but of the

promotion of a native. It has been an illustration of the "survival of the

fittest." I have lately had the satisfaction of seeing this fine old man -

Allan Macfadyen - hale and vigorous at the age of eighty-six, the tenant of

the largest part of the whole farm, and sharing it with one other only of

the original crofters, who has risen like himself out of that class, and now

holds a little farm above the £30 line.

There are several other farms on the Island which belong

to the same class, ranging above £50 and below £200 a year, and these are

all occupied by natives of the Island, who once had much less comfortable

possessions. With regard to the old farms of still larger size, which had

long been held by individual tenants of the "Tacksmen" class, and had never

been subdivided, none of the crofters have had capital enough to start them,

or knowledge to manage them to the best advantage. Nor has this been

otherwise than a great benefit. The jealousy of: "strangers" coming into

such farms is perhaps the: most ignorant, if it be the most natural, of all

the Protean forms which the desire of "Protection to Native Industry"

assumes. Nothing tends more directly to the stagnation of agriculture in

such a distant Island as Tyree than that its people should never see the

example and results of a higher agriculture than that which has been

represented by their own old habits and traditions. The introduction of new

blood is the greatest of all stimulants in such districts, and without it

there would be no advance.

I can specify one signal illustration. The pasturage of

Tyree is particularly rich in clovers, and in grasses of the most nutritious

kind. Consequently it is admirably and almost specially adapted to

dairy-farming. But dairy-farming was wholly unknown in the Island until I

took pains to introduce it. The breeding of Highland cattle and of sheep,

together with the growth of potatoes, barley, and oats, constituted the

whole agriculture of the Island. But when the large farm of Bahephetrish

became vacant some twenty-two years ago, I instructed my factor to look out

for a tenant from the low country who should be a dairy-farmer. The

disadvantages of residence in a remote Island, the character of which was

little known in the low country, made this a matter of some difficulty, and

involved a very considerable outlay in buildings adapted for the purpose.

But a tenant was found. The experiment has answered perfectly. The pasturage

of Tyree has proved itself to be admirably and specially adapted to the

production of cheese of a high quality, and to the healthy condition of a

fine herd of first-class Ayrshire cows. I have had the pleasure lately of

renewing the Lease to the son of the tenant who began the enterprise, Mr.

Barr of Balephetrish, and who, I have every reason to believe, found it

profitable. But this kind of farming, for which the rich and abundant

pastures of Tyree are more suited than for any other, is one which cannot be

adopted by very small crofters. I am not without hopes that it may be

prosecuted, by crofters of the more substantial class, at some future day,

when the great care and great cleanliness which are necessary for the

production of really good cheese and butter have been established.

established among the people.

I am happy to say that I have seen great progress among

the crofters during the thirty years and upwards which have elapsed since

actual distress ceased. For a good many years, it required stringent rules

and regulations to establish anything like a regular rotation of cropping.

Nor is this to be wondered at, considering the very short time which had

elapsed since their fathers knew nothing better than the old barbarous "runrig"

system. The cultivation of the crofts still leaves much to be desired. The

little corn-fields are often yellow with weeds. But some turnips are now

cultivated, and there are crofts in which a marked improvement has been made

on the old traditionary system. I have been lately offering some prizes for

the best cultivated crofts, and the judges have informed me that the number

of tenants who have done well in this matter has made selection difficult.

These are only special cases, which illustrate the system

I have pursued, and the nature of a process which has produced a marked and

steady improvement in the condition of the smaller tenants. In direct

proportion as the most capable among them have been selected for the

enlargement of their possessions, and as progress has been made towards the

establishment of a variety of large crofts and of small farms, the general

level of the whole population has been distinctly raised. Some special

circumstances affecting Tyree make it more favourable than other, districts

in the Highlands for small farmers. In the first place, although it is much

exposed to gales of wind, and there is comparatively little shelter, yet the

climate in other respects is far better than that of the mainland. There is

much less rain, the rainfall scarcely exceeding the average of from 35 to 40

inches. [I fully expect that "far on in summers which I shall not see" the

Island of Tyree will be a great resort for health. Its strong yet soft

sea-air—its comparative dryness—its fragrant turf, full of wild thyme and

white clover—its miles of pure white sandy bays, equally pleasant for

riding, driving, or walking, or for sea bathing— and last, not least, its

unrivalled expanses for the game of golf—all combine to render it most

attractive and wholesome in the summer months. My own tastes would lead me

to add as a special recommendation its wealth of sky ringing with the song

of skylarks, which are extraordinarily abundant] There is also a great deal

more sunshine than on the mainland. Snow hardly ever lies. The pastures are

naturally very rich. Moreover, the island is admirably suited to poultry,

and there is annually a very large export of eggs, amounting, I have reason

to believe, to not less than 50,000 dozen. This export represents a revenue

to the small tenants from this source alone of at least £1,500. The lighter

soils produce good barley and excellent oats—crops which are early ripe—and

if the sowing were a little earlier than the traditions of the people have

made it, the harvests, I believe, would more often avoid the severe gales

which not infrequently do considerable damage. Then, potatoes have often

escaped the disease in Tyree during seasons when it was destructive on the

mainland, and a few years ago high prices were obtained by the tenants for

the seed potatoes which they raised. Lastly, the quality of the cattle,

which is one of the staple products of the island, partakes of the superior

quality of the pasture on which they feed, and I have endeavoured, by

arrangements for the occasional purchase of good bulls, to prevent the

decline in that quality, which is very apt to arise among crofters who have

not capital to buy in good new stock with sufficient frequency.

From all these causes combined, I rejoice to say, that

during the last thirty years I have had every reason to be satisfied with

the small tenants of Tyree. Until quite lately there has been very little

arrear, and they have met their engagements honestly. They have been a

quiet, sober, industrious, and generally a contented people. I have been

accustomed to regard them with some pride and satisfaction, as decidedly

superior to others of the same class in most other portions of the West

Highlands. During the last two seasons there have been some disastrous

gales, an unusually heavy rainfall, and some renewal of the potato disease.

But the general prosperity of the tenants has been apparent in everything,

and in nothing more apparent than in the comfort of their houses, which are

peculiar, and indeed unique in warmth and in solidity among the cottages of

the West Highlands. It will be observed that all the articles which Tyree

produces, and on which the small tenants depend, are articles in which there

has been no depression of prices, but on the contrary a great increase.

Wheat is not grown on the island, and wool is an article upon which the

crofting tenants do not largely depend in Tyree. Barley, oats, and potatoes

have maintained fair average prices for many years, and there has been an

immense increase in the price of the class of cattle on which the crofters

principally depend. At no time has the price been so high as during the last

few seasons. Tyree, therefore, cannot he said to have been exposed to any

one of the causes which have produced agricultural depression in other parts

of the kingdom. The only special cause injuriously affecting the crofters

has been the occurrence of one or two wet seasons, and the occurrence also

of some great gales of exceptional violence before the harvest had been

secured.

This general conclusion as to the exemption of Tyree from

the causes which have elsewhere produced agricultural depression, is a

conclusion established by the most conclusive of all proofs, and that is the

steady rise in the letting value of laud. And this rise has been tested by

the simplest and fairest of all tests—which is the price voluntarily and

eagerly offered for the hire of land by farmers of the capitalist class

bidding for the larger farms which have been open to competition. It is to

be remembered that as regards this class of tenant, the doctrine lately laid

down by Sir James Caird is absolutely and literally true, that the rent of

land is not determined by landlords but by tenants. As regards the small

crofters, this doctrine is modified to some extent by the local attachment

of a population, which may sometimes be induced to bid above value by the

desire or determination to remain where they are even at a sacrifice. But

there is no such element in the value set upon land by the capitalist class

of tenants, whose action is entirely determined by an intelligent

calculation of outlays and returns.

Taking this test, and applying it to seven of the larger

farms in Tyree, I find that on these farms the rental of 1847 has been

increased by about 220 per cent. The figures are—rental of 1847, £700.

Rental of 1883-84, £2260. I need not point out to your Lordship (although it

does seem necessary to point out to many other people) what this more than

tripling—in some cases the quintupling—of rental means. It means an enormous

increase of production. As rent is seldom more than one-third, and is

oftener not more than one-fifth of the total produce, the above figures mean

that the seven farms in question now turn out at least £6780 worth of human

food, instead of food to the value of only £2100.

This great rise of rent is not to be considered as an

example of any ordinary increase in the value of agricultural land. I have

elsewhere said that the first application of sheep to the mountains of the

Highlands was like the recovery of an immense area of country from the sea.

It is as stupid to object to it as it would be stupid to object to the

drainage of the "Bedford Level." The increase of value which has arisen on

some farms in Tyree, consequent on my change of management, is an increase

of a similar kind. It did not indeed arise as elsewhere on mountain land,

but on land arable and naturally fertile. But it did arise out of a series

of operations which have been equivalent to absolute reclamation from utter

waste. It is an increase of value measured not only by the height of a new

knowledge, but by the depths of a former ignorance. And this is the great

lesson to be learned from corresponding increments of value which have

arisen all over the Highlands. The squalid wretchedness of the older modes

of living and of husbandry, from the want of capital, and of knowledge, and

of industry, is the great fact to which it testifies. Such "leaps and

bounds" in productive value are not possible in any country where the

culture of each generation keeps abreast of time general line of progress in

its own day. They are only possible where there have been utter stagnation

and positive as well as relative decline. And this was the actual condition

of the Highlands during the times I have traced, from the rate of increase

in population, coupled with no increase at all in knowledge, or in capital,

or in industry. Hence, when all these conditions began to be reversed, a

contrast arose with the former wretchedness which seems incredible. So it

has been with the productive power of land in Tyree, where— but only

where—the farms could be rendered accessible to modern methods. This is the

explanation of the increase of rent upon such farms.

It is quite exceptional. It is more like the increase of

value which arises on the discovery of a new country. It may almost be said

to represent the first advent of civilization in the settlement of a new

land. The truth is that under the former system it can hardly be said that

the land was cultivated at all. It was simply wasted. The new value is a

value both discovered and created. It has arisen from the finding out of

adaptabilities unknown before, and from management which has turned these

adaptabilities to good account. By that management I have been enabled to

realise the prophecy made by Mr. Maxwell of Aros eighty years ago, that the

Island of Tyree was capable of producing returns of which the people then

"had no conception." The realisation of this estimate has been the combined

result of several causes—some of which may be specified:—first, there has

been very large outlay by the proprietor in draining, fencing, and building;

secondly, there has been the introduction of a new class of tenant bringing

into the Island a new industry, that of dairy farming; thirdly, there has

been the increased facilities of steam communication with the Island—almost

comparable with the approach of a new line of railway on the mainland;

fourthly, there has been the great rise in the value of sheep and cattle,

and the newly-discovered adaptation of the Island to the production of

superior stock and of early lambs; and last, not least, there has been the

substitution of men who prosecute farming as a business for men who simply

looked upon a farm as a dignified means of living without the necessity of

much. skill or the exercise of much activity. Perhaps there has seldom been

a case in which we have a more signal illustration of the fundamental value

of that old doctrine of the law of Scotland which makes the "Delectus

Person"— the choice of persons, or the right of choice in the selection of

tenants—the most essential of the duties and of the rights of ownership.

Without this right, and that intelligent exercise of it which is guided by

the most natural and legitimate motives, I am satisfied that there would

have been no increase in the agricultural produce of Tyree comparable to

that which has actually arisen, and the Island would have remained in a

comparatively stagnant, if even it had not fallen into a declining state.

I have brought these facts and considerations under the

notice of the Commission because they afford one very good criterion of the

justice of any complaints made by the smaller tenants as to the rents they

pay. I know of no class of men who deal in the hire or purchase of any

article, who would not eagerly testify to any Royal Commission that they

would like to get that article cheaper. In respect to no article would such

evidence be more eager than in respect to the price of cattle in which these

small tenants deal, not as purchasers, but as sellers. The larger farmers,

who deal in fat stock, have every cause to feel the stress of the very high

prices which they are now compelled to pay to the producers of lean stock.

They say that these prices leave them no margin for profit on feeding. The

small tenants, however, would hardly admit such an argument as calling for

any abatement of the price which the markets afford to them. Yet their own

complaints are not more reasonable. Their possessions are really worth

double or treble of what they were worth thirty-five years ago. Many of the

causes which have led to the rise in the value of land which has been so

signally proved in the case of the large farms, have been even more

applicable to them. In particular, the great rise in the value of cattle,

and very often of potatoes, they have had the full advantage of. The

increased facilities afforded by steam communication have been of equal or

even greater value to them in proportion as they have told on the prices of

pigs, eggs, poultry, and fish. The breeding and sale of horses have also

been a great source of profit—very little considered in the rent. Yet it

will be found on comparing the present rental of farms which are still

divided into small crofts, with the rental of the same farms as it stood

thirty years ago, that the rise of rental has been comparatively small—in

some cases quite trifling, and has borne no proportion whatever to the rise

in the real letting value of the land as tested by the rent readily obtained

for larger farms in the open market,—that is to say, when estimated

according to the capabilities of the soil by men with adequate capital who

know how to turn these capabilities to full account. The truth is that, if

we go back to a still earlier date, such as the years at the beginning of

the present century, there has been on some of the farms divided into crofts

not an increase but a positive decrease of rent. This has no doubt arisen

from the fact that at that time there was some mingling of kelp-rental with

agricultural rental, and that when the kelp failed there was some

readjustment of rents which were not purely agricultural. The only

considerable rise in crofter-rental since 1847 has been on the larger

consolidated crofts, and on the small farms erected out of them. It is

needless to say that consolidated crofts are always worth a great deal more

than the mere sum of their rents when separate. They can be more

economically worked, and there is a much larger proportionate surplus over

the cost of working. This alone accounts for all the rise of rent which has

accrued on the more comfortable possessions, whilst on many of the smaller

crofts the increase of rent has been almost nominal as compared with the

real increase of value.

Another test of rental may be taken from the careful

survey and valuation made in 1771, at which time the Island was calculated

to hold 2488 "soums" of cattle. This represents the same number of cows, and

double the number of young cattle. Now, as the average rental of a good

Highland cow with its "followers" upon such pastures is at present about £3,

it follows that the stock fed by the Island of Tyree, without allowing

anything for the improved pastures gained by drainage, and the improved

facilities of management gained by fences, would represent a rental of £7464

—which is a great deal more than the whole rental of the Island as it stands

at the present moment. Moreover, it is to be observed that this calculation

excludes all the other produce of the Island—the sheep, horses, and pigs,

the barley, oats, potatoes, and eggs, which it produces in abundance.

Farther still, it is to be noted that Ayrshire cows have been largely

substituted for Highland cattle, and that one Ayrshire cow is worth about

double the rental which is taken above as that for a Highland cow. I have

reason to believe that there are in the Island not less than 247 Ayrshire

cows, 2155 Highland cattle, 6500 sheep, 651 pigs, and 588 horses. It is

curious that this amount of stock, calculated at rates somewhat below the

market value, and allowing nothing at all for either horses or pigs,

represents a rental almost exactly the same as the rental calculated on the

old " Souming," namely, about £7400.

Perhaps I cannot use a better illustration of the scale of

rents in Tyree, than by taking an individual case. It happens to be one of

those many widows of whom the agitators have asserted that they are as a

rule evicted on my estate. The figures have been supplied to me, not from my

own agents, but from a less suspected source. It is the case of a croft

rented at a little more than £24. It is now reported to me as holding 7 milk

cows, 2 heifers, 8 "stirks," and 40 sheep. This amount of stock at the usual

rates would represent a rental of about £31; and would unquestionably fetch

that rent, and more, if let at the market value.

Taking all these data together, it seems quite clear that

the crofters' lands in Tyree are held generally at rents far below the full

value, and such as readily to account for the comparatively comfortable and

thriving aspect of the Island and of the people, as contrasted with most

other parts of the Highlands which are occupied by a similar class.

Passing now from the crofting and farming population, I

wish to bring to the notice of the Commission that in Tyree there is a very

large population of mere cottars, some of whom live by fishing, others by

labour obtained in the Island, and others again by going to service for some

part of the year to the low country. This population may be said, in the

language of geology, to be the detritus of the old subdivided crofters and

subtenants. I believe there are no less than about 300 families who live on

the Island without paying any rent either to the proprietor or to the

tenants. Some of them are brave, hardy, and successful fishermen, who in

some seasons earn a very fair living, and furnish a very considerable export

of salt fish. The annual average export of salt fish does not tall short, I

believe, of 100 tons—a quantity which, however considerable (representing

not less than £2000), might be and I hope will be, much increased. Among the

natives of the Hebrides who were helped to come up to see the late Fishery

Exhibition in London, there were no finer-looking men than some fishermen

from Tyree, and I felt no small pride and pleasure in their appearance when

they called upon me in London. The harvests of the sea are more precarious

than the harvests of the land. But the season of 1882 was one of the best on

record; and the price of good salted lung rose to the high figure of £30 per

ton. The fishermen of Tyree labour under a great disadvantage in the want of

any really safe and commodious harbour. The only natural harbour is not only

a tidal one, but the entrance is very narrow. On the west side of the

Island, which is nearest some of the best fishing-banks, there is nothing in

the nature of a harbour except some rocky bays, the entrance to which

involves considerable risk in dark and stormy weather. Yet for many years

fishermen from the East of Scotland have come regularly to Tyree, and have

carried off valuable cargoes of the finest salt ling. A good many years ago

I bought and fitted out one of the large powerful boats which are used by

these East Country fishermen, and some good work was done in her by the

natives of Tyree to whom she was lent. Of late, too, I have again offered to

two of my tenants who are enterprising fishermen a loan to enable them to

provide a new boat of the same class; and I hope this may soon be effected.

I regret to add that the advice of the most eminent engineers does not

encourage me to believe that on the open and stormy shores of Tyree exposed

everywhere to a tremendous surf—it would be possible to construct any really

safe harbour at any moderate, or indeed almost at any cost.

I have said that the cottar population of Tyree is the

detritus of the old subdivided crofting population but I ought to have added

that it is also in great measure the remains of the old kelp-burning or

kelp- gathering population, which had once been so lucratively employed. And

in connection with this subject, I have to relate to the Commission some

circumstances which exhibit in a very striking light the fact— too often

forgotten—that the wages of the labouring classes generally depend on

influences to which they themselves contribute nothing. There are, perhaps,

no sources of income so entirely due to the general progress of society, or

very often to the brains and inventiveness of other men, as the

opportunities of labour. The circumstances to which I refer are these. The

kelp trade had entirely ceased long before the potato failure of 1846. A few

tons were occasionally bought at a trifling price by some manufacturer in

Glasgow, but as any important resource to the population in the earning of

wages it had entirely failed. It was under these circumstances that,

twenty-one years ago, a copy of the "Pharmaceutical Journal of London" came

under my notice, which contained an interesting paper on the products of

seaweed. In this paper it was shown, as it seemed to me to demonstration,

that there were very valuable elements in seaweed, which were entirely

dissipated and lost by the old native mode of manufacturing kelp. That mode

was the burning of the seaweed in open kilns along the sea-shores; and the

author of the paper showed that this burning was most wasteful, and that, in

particular, almost all the iodine—at that time a most valuable product-was

evaporated in the fire. I was so interested in this paper, both in a

scientific and in a practical point of view, that I put myself in

communication with the author, Mr. C. C. Stanford. I laid before him all the

doubts which occurred to me whether the result of experiments on a small

scale in the laboratory would be borne out when like chemical operations

were required on a large scale, and in respect to so bulky a material as raw

seaweed. On his replying to the effect that he was satisfied of the

soundness of his calculations, I informed him that I could give him an ample

field to work on, the shores of an Island which had once supplied annually

from 200 to 300 tons of the old kelp;- that if his calculations were even an

approach to the actual results, the profits would be large to him, and would

afford once again an important industry to the people. He answered that he

was unable to supply the considerable amount of capital which would be

requisite, and on this ground alone declined my proposal. A few days later,

however, he informed me that he had reconsidered the matter, and thought he

could get together a small company which should undertake the experiment.

This was the origin of the Seaweed Company, which has since for twenty years

effected an important revival of the trade in seaweed and its products.

Continued changes in the market price of some of these products, arising out

of new mineral sources of supply, have since greatly deranged the original

calculations of Mr. Stanford. The rent he originally agreed to pay has never

been fully realised, and has now been reduced to an inconsiderable sum. But

his processes have not ceased to furnish employment to a large number of

persons, including women and children, who could not otherwise have had any

employment at all. I have been informed that in the season 1880–1881 the

people of Tyree made no less than 376 tons of kelp, and gathered no less

than 417 tons of "dry tangle," which, at the lowest calculation, must have

dispensed among the poorest classes not less than between £2000 and £3000.

Whatever may have been the amount of wages expended by this Company among

the working classes in Tyree,—and that amount must in the aggregate have

been very large during the last twenty years,—the whole of it has been

brought to them from causes to which they contributed nothing. It has been

due, in the first place, to Mr. Stanford's scientific knowledge and skill.

It has been due, in the second place, to the proprietor's notice and

appreciation of the prospects which Mr. Stanford's experiments afforded; and

it has been due in the third place to the proprietary right under which