45. What Type Do We Need for the West?

One of the most frequent questions I am asked is, "What

do you reckon is the best type of cow for a crofter?" It is a question I

never answer in a hurry, because there is no easy reply. I could much better

give a quick answer on the kinds of cow which would be unsuitable for

the crofting areas as a whole. We are down to the old facts again that our

western countryside is short of lime and phosphates, both of which soil

elements are highly necessary for a copious and persistent supply of milk.

The student at an agricultural college learns the

economics of the living animal body. He is taught quite properly that the

essential food intake of a beast varies not in direct relation to its

weight. For example, the area of body surface of a mouse is much greater in

proportion to its weight than is the surface area of a cow in proportion to

her weight. According to the books, then, a good big cow is more economical

than a good little one, for her efficiency in conserving heat is greater

(and heat means food in the first place), and her overhead charges in the

shape of attention, byre space, milking and so on are less in proportion;

that is, if eight big cows will give as much milk as ten smaller ones.

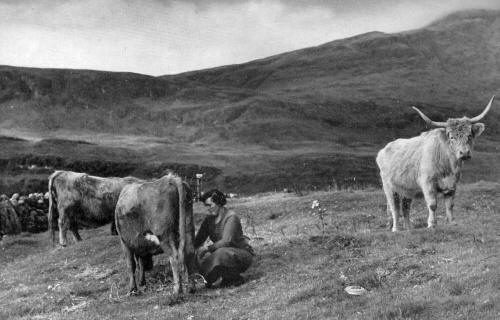

MILKING TIME, TORRIN, SKYE

The Highland breed may be reckoned a beef breed

primarily, but useful milkers can be found among them. One of the great

advantages of Highland blood in the crofter's cow is the placidity which

is such a marked characteristic of the breed. It is much easier to be

able to go out to the cow on pasture in summer than to bring the cows

into the byre—and a good way of ensuring clean milk. From the position

of the lid of the pail and of the cow's muzzle, it looks as if this

beast was inclined to move on during the milking.

I have no fault to find with the books: they are quite

right, and the farmer on rich dairying land is well advised to keep big

cattle such as Friesians, Dairy Shorthorns and Red Polls. But we are on thin

hungry land, with a lot of our grazing on peat. We know by hard experience

that practice in the West cannot always follow the books. Or should I say we

need a new book, dealing entirely with our own countryside?

The first thing I should say about the crofter's cow is

that she should be small. We cannot afford to fill the belly and cover the

ribs of the big cow, nor is our ground good enough yet to grow the bones of

the big cow's calf. We need a beast that can face a period of short commons

without falling to pieces on us, and on the whole it is the little beast

that will face such conditions best.

There is the type of cow that puts every extra ounce of

food you give her into the pail and milks herself to skin and bone.

Such a beast, calving in late autumn or winter on an ill-provisioned croft,

may have to be carried out to the grass in May and is a tax on the nerves of

a kindly owner. There is also the type of cow which puts everything on her

back and is dry in six months. She is a tax on the owner's temper as well as

on his pocket!

We need a cow that can "reef in" as you might say and

trim her sails to the nature of the blast; that can place her food first of

all to the maintenance of her body in good lean condition, and all food over

and above that into the pail. When she is outside, we need a cow that can

walk well, graze wide and feed as well from the moor as from the grass

parks. We also want a cow not too thin in the skin and that can grow a good

coat for the winter.

We may say, then, that the crofter's cow should be

neither of extreme dairy type nor of extreme beef type. The books talk of

dual-purpose animals which can milk well and be fattened to a good carcass.

But our cow has to be treble or quadruple-purpose in type if she is to be

the perfect cow for the crofter. Our arable land is small in extent and we

can never properly allow ourselves to breed a type which is more or less

bound to that bit of arable land. We must never forget the great background

of hill grazing which the calf of the crofter's cow should help to utilize

profitably. If we say we will be sure of heavy milkers and then stock up a

township with Ayrshires, our bull calves are worth thirty shillings and we

are without rough cattle for the hill. Even if we have a black polled bull

and get black calves from our Ayrshires we are not really playing fair by

the man who buys those calves, not knowing the Ayrshire side of the

parentage, for they will never make good bullocks. Unless we have a ready

market for milk or dairy produce, and if our arable ground is not in

sufficiently good order to grow a variety of winter fodder and roots, we

must go for something different from a pure dairy breed. Even the Kerry, the

little black cottar's cow of the west of Ireland, though a good milker and

well suited to our conditions, would not necessarily be the best to stock

the countryside with in large numbers, because she would not be breeding

that class of rough, hill-grazing bullocks which should be a mainstay of our

husbandry. Incidentally, as a bit of history, I have recently learned that

Kerry cows were once kept on this island of Tanera and were good, thriving

beasts for the crofter-fishermen of the period. They came here by sea in the

old fishing smacks which carried to Ireland the red herrings which were

cured on Tanera. The Kerry cow produces a better cross bullock with the

Shorthorn than does an Ayrshire.

Let it be admitted, then, that there is no pure breed of

dairy cattle which would make the perfect crofter's cow. We must look to

crosses, but unless we have a carefully controlled system of breeding

throughout the West Highlands we are likely to find ourselves with the

oddest collection of cattle one could imagine, and that would depress the

store market, for buyers like uniformity.

If I were allowed to be completely honest and candid, I

should say we are getting well on to that condition now. There is too much

whim and fashion in this cattle-breeding business. Someone decides to keep a

certain breed of cow in a district, come what may, and you find in a few

years that many of the cattle in the whole neighbourhood are streaked with

this breed. That is the result of one man's whim. Fashion also seems to me

to go mad at markets. Dingwall wants Blacks and will pay a pound extra for a

few blue hairs. Perth and Stirling want Shorthorns and Shorthorn-Highland

crosses, except for the specialized demand for Aberfeldy blacks. Highlanders

were hardly paying their freight to Dingwall before this war, yet Oban was

reckoned a dear place to buy them. The layout of railways and the fashion of

markets, then, seem to impose the colour and breeds of cattle kept on the

western grazings to a greater extent than the conditions in which the cattle

are bred. We certainly need a safeguard somewhere to ensure that the breeds

are not crossed out of existence in the West, but the fact remains that the

ideal crofter's cow is probably crossbred and we will consider her parentage

in the next section.

46. Crossing for a Desired Type

We have come to the conclusion that the perfect crofter's

cow apparently does not exist as a pure breed, but that she may be found as

a cross. The question is, what cross?

There are two basic pure breeds of cattle which can take

full advantage of West Highland grazings—the Highland breed and the

Galloway. As far as can be seen there is no difference in hardiness; the

Galloway is undoubtedly earlier maturing, but the Highlander will

probably graze rougher stuff and farther afield. Both breeds

cross well with the Shorthorn and there is an extensive trade in these

crosses. I have both publicly and privately advocated an extension of the

Galloway breed into the West Highland area, but in doing so I do not wish to

belittle the place of the Highlander, for the Galloway is not a crofter's

cow, in my opinion. The breed as a whole tends to be nervous and the cows

are sometimes difficult to handle, whereas no breed of cattle in Britain is

more docile than the Highlander. That docility and placidity of temperament

is a most valuable attribute which usually appears in the crosses. Neither

would I say the Highlander is a good crofter's cow. She does not like the

byre and can be quite a fussy feeder when confined there. She does not carry

milk for ten months of the year and has a natural tendency to spring and

summer calving.

The great value of the Shorthorn is its power to stamp

quality and conformation on its crosses. It has played an immense part in

grading up the cattle of the Americas. Here in the West Highlands the

Shorthorn bull is still used as a crossing beast. He seems to nick

particularly well with the Highland cow. As markets and demands for store

cattle are at present, and with even our arable land in a relatively

unimproved state, I believe the best general type of cow for the crofter

would be a Shorthorn-Highland cross. This beast is hardy, it will give a

fair drop of milk for nine or ten months of the year if given reasonable

treatment, and it will cross well with either Shorthorn or Aberdeen-Angus to

produce calves for the store trade. The quality of very high butter fat

content of the Highland cow's milk is often transmitted to the cross cow.

There is one part of the West where I would favour the

pure-bred Ayrshire: that is in the Island of Lewis.

The conditions here are quite different from elsewhere.

The dense human population keeps cows for one reason only—milk. There is

practically no store trade and the peat bog which is the middle of Lewis has

not the grazing quality of the hill land which backs most West Highland

townships. The type of Ayrshire for Lewis is not the highly developed cow

which wins the London Dairy Show, but the smaller beast of the hill farms of

Galloway which can grow a good coat and winter out. The Ayrshire is already

largely kept in Lewis, but there is need to see that the duds from flying

herds in Stornoway do not drift into the crofting districts.

In praising this Shorthorn-Highland cross for the

crofter's cow, I do not wish to be contemptuous of many a nice little blue

cow I have seen about the Highlands, obviously sired by an Aberdeen-Angus,

but I hold nevertheless that Angus crosses will not produce the equally

hardy, reasonably milky sort as commonly as the Shorthorn-Highland,

especially if Shorthorn bulls for the Highlands are chosen from good rearing

strains. It is a pity that the Aberdeen-Angus men have lost the milking

capacity which undoubtedly existed in their cattle. Seventy or eighty years

ago there were black polled cows giving well over five gallons a day. The

Aberdeen-Angus does not cross well with the Highlander.

Beefy types of Cumberland Dairy Shorthorns might be used

for crossing with the Highland, but care would have to be taken to keep out

the long-snouted type which has recently tended to spoil the look of that

breed. The man buying rough stores will not stand for long snouts ! The

Lincolnshire Red Shorthorn is also worth trying.

It remains to be said that we need to bring order into

our cattle breeding policy. Somebody must keep the pure breeds and leave

most of the second crossing to the crofters. The State, the lairds and the

large farmers are the ones to keep up the main herds and make the first

crosses for sale to the man who keeps only one, two or three cows, Some

organization of this kind would make for more uniformity and save the

markets from some of the sketches of animals which come in from time to time

just now.

47. Making a Breed

We have been considering in previous sections the virtues

of the crofter's perfect cow and have come to the conclusion that they are

not all to be found in any one breed, but let it be admitted that occasional

perfect cows turn up in many pure breeds as well as in crosses. I have just

seen a beautiful Shorthorn cow which has never lived anywhere else but on a

croft. She is giving nearly five gallons a day, and that cow has been inside

on only two nights during the past winter. It was not that she was pushed

out; she was given the choice of a shed with the door left open and she

preferred to go out. That cow is in good order now at the end of May, yet

has had nothing but good hay and such small cake rations as have been

available. Her seven-week-old blue calf by an Aberdeen-Angus bull is one of

the best I have seen for years. Candidly, I don't know how it has been done.

Unfortunately, we cannot pick up pure-bred cows as good

as that one every time we go near a cattle sale. It is often said, why can't

we make a breed by crossing individuals of different breeds, each of which

has some of the characteristics we want in our perfect cow? The fact is that

one of the hardest things a breeder can undertake is to make a new breed of

cattle, sheep or horses. Almost anyone can produce a uniform and profitable

lot of first-crosses—that is just plain commercial practice—but the

difficulty comes when you start breeding from these first-crosses. The

characters you started with in the original breeds begin to separate out and

you find yourself with a bunch of cattle odd in colour and type. It is

certainly no game for the crofter with his very few cows.

In breeding from these good, level first-crosses we may

get one or two beasts which approach our ideal type, but at what cost! One

or two out of fifty or sixty perhaps. It would take years and years to work

up a good stock of a new synthetic breed. Mind you, it has been done in the

past, and in the very near past. For example, the Corriedale sheep which is

so popular in New Zealand, Australia and South Africa, was evolved in living

memory in New Zealand from judicious mixing and fixing of Merino, Lincoln

and Romney Marsh blood. The proprietors of the immense King Ranch on the

Louisiana shore of the Gulf of Mexico have developed a polled red breed from

the Indian zebu and red European cattle, which gives them a good beast

resistant to disease and able to graze far afield. They call it the Santa

Gertrudis breed.

The Thoroughbred horse, the flower of English

stockbreeding, was fixed from a mixture of Barb, Old English mares and

perhaps a little Arabian blood.

Nevertheless, we have not produced a pure breed of that

famous first-cross sheep, the Half-bred. Some people have thought it could

be done, but an analysis of the wool of such a flock has been found to vary

widely from Border Leicester to Cheviot type. And we have not developed

Blue-Greys as a pure breed, because it cannot be done ; two blues produce

one black and one white calf out of every four.

If making a new, synthetic breed is difficult and

unprofitable, we must continue to produce those first-crosses which are

known to nick so well, such as the Half-bred, the Blue-Grey and the

Shorthorn-Highland, but at the same time such improvement as we wish to

bring about in pure breeds will be best done by selection within the breed

and not by introducing dashes of this, that and the other. That is how the

best breeds have been built up and maintained.

48. Care of the Milk Cow and Her Calf

A crofter's wife whose husband is a prisoner of war

recently asked my advice about the care of the cow at calving and the

rearing of the calf. Her neighbours had been kind in offering help and

advice, but she found herself confused by the multiplicity of counsel, and

she appealed to me for solid reasons why certain things are done or not

done. Should you help a cow at calving? Should you let the calf suck her?

Would you milk her straight away, or, if not, how many hours after calving?

Should you milk her out the first time? How soon should she go outside? How

much milk should the calf have and how often? Should food be cooked for the

cow? All these questions need careful replies and every case must be

considered in relation to its own set of circumstances. Nevertheless, there

are certain sound lines of procedure which can be set down as a basis.

FETCHING PEATS, BARRA

A lot of work went into making these turf-covered

stacks of peats before the final job of fetching them in, and work at a

time of year when we should be cleaning the land. Let us hope that

hydro-electric power in the West may make a good part of this work with

the peats unnecessary.

This Barra pony is a useful friend. It is a pity

these hardy beasts are not more generally kept and worked with creels.

Coup carts need roads which we cannot have everywhere, but a pony with

creels can carry peats, potatoes or seaware out of many an awkward place

and make the work of the croft much lighter.

My own feeling is that many crofters' cows have a mixed

life of hard doing and undue coddling, and the feeding in winter is not as

well balanced as it might be. I know quite well that some of the advice I am

going to give in the following two or three sections is that of perfection

which the average crofter cannot put into practice, but it is as well to

know what would be the best treatment and then to approach it as nearly as

possible in practice.

First of all, let us consider the cow before she calves.

If we want her to milk well we must put good food into her beforehand. A

period of six to eight weeks of good feeding before calving is essential if

the cow is to do as well as her breeding would allow her to do. All too many

crofters' cows calve in spring, which means a good price for the calves and

no milk for the house for most of the winter. Until we can grow more winter

keep by better treatment and more intensive cultivation of our small area of

arable ground, and by better methods of conserving the good grass we shall

then grow, it is perhaps inevitable that 90 per cent. of the cows must calve

in spring because there is not the feed to keep them milking in winter, and

they are not in the condition to take the bull between December and March to

give us winter calving. If we do calve a cow in September or October in the

Highlands we need not bother too much about the stoking-up process

beforehand, because she will be in the best condition she is likely to reach

in the year and will have had the picking of the stubbles as well as the

best of the hill. Peace-time conditions would indicate 4 to 7 lb. of oil

cake a day for six weeks before calving, but just now she would have to do

with little or none, except where a crofter is definitely selling milk in

his district, in which case he is allowed an oil-cake ration especially to

bring his cows into condition for winter milk production.

Personally, I like to calve my cows indoors even if it is

the height of summer. This is not because the cow would hurt outside, but it

means less trouble about the calf. If a cow sees her calf and licks it and

has it sucking her, she quite reasonably wants to keep it and kicks up a

fuss when we take it away. All fuss means loss of condition. There should

never be fuss where milking cows are concerned. If the cow calves inside in

your presence, you can put the calf into its pen before she sees it, and rub

it dry yourself, and then she does not worry.

The average gestation period in dairy cattle is 283 days,

but there is a good deal of variation up to five days or so either side of

this figure. The man with the practised eye and hand does not spend

fruitless nights out of bed looking to see if the cow has calved. He reaches

the state when he can say, "She will calve in the next twelve hours," and be

right. Signs of approaching calving are fairly well known—the enlargement of

the udder and of the passage, and the "giving" of the "gristle," but I have

found that many people are inclined to pay too much attention to the state

of the udder as a sign, and not to understand completely the surest

criterion, the state of the gristle. The gristle is the cartilage which runs

from either side of the tail head to the pin bones. As calving draws near

the gristle slackens in the middle and allows the pin bones to widen for the

ultimate passage of the calf. The touch of the experienced hand will tell

when the gristle finally gives on either side; when that happens the cow

will calve within twelve hours.

A cow which is normally outside day and night, or in the

daytime, will not catch a chill by being left outside till the last moment

before she calves. It is better that she should be out, and in most cases

there is little harm in calving outside, even in winter. The possibilities

of catching a chill, which may mean the death of the cow, come in the few

hours after calving, even in summer. For example, suppose a cow

calves at two o'clock of an August morning and there is rain and a bit of

south-west wind. If she is outside then, she is in serious danger.

The act of calving produces a general temporary lowering

of body tension and pressure and there is a certain amount of shock. It

should also be remembered that the birth of the calf means a considerable

amount of heat is lost from the cow's belly but not an equivalent amount of

mass or surface area. Rain falling on the cow at this time would in itself

be chilling, but we know also that evaporation of moisture consumes heat

(you will have noticed the feeling of coldness when a little methylated

spirit spills on the fingers), so that the cow's body would be losing warmth

much faster than her temporarily lowered system would replace it. Wind is

also a great remover of heat.

One likes to be present in the byre with the cow when she

actually calves, not only because help may be needed, but if your cow is

your friend—as she should be—she will gain comfort and confidence from your

being there. My feeling is that in all normal calvings, you are better

occupied at the head giving her a bit of petting than in any interference at

the tail end. If you have to help pull, pull only when the cow strains, and

in a downward, not outward, direction.

The calf should be put into a calf-pen straight away and

rubbed dry with dry bracken or straw. The rubbing gives it stimulation and

prevents chilling by too rapid evaporation of the moisture. Calf-pens should

always be thoroughly cleaned out, disinfected and whitewashed and rebedded a

good time before the new calf goes in. This is not fussiness or

over-cleanliness, because infectious white scour is a really dreadful

disease in calves, and it should never occur. Strict cleanliness and not

buying in calves is the surest way of keeping clear of it.

The first thing to do after the cow calves and the calf

is penned, is to give her an oatmeal drink. (In wartime, however, it is

illegal to give oatmeal to an animal.) Oatmeal has great restorative value.

Put about a pound in a pail, mix to a paste with cold water, then add a

kettle of boiling water, and stir and work it so that no lumps form. Fill up

to about two gallons with cold water and offer it to the cow. If she drinks

the lot and leaves a bit of meal at the bottom of the pail, she can have it

half full of cold water again. Cows will often refuse warmish water, and

they seem none the worse for having their drink cold at this time.

The cow is best left alone for an hour or so with what I

call a hatful of as good hay as you have got. She needs rest and quiet. If

you have ever watched cows or hinds calving in the natural state on the

hill, you will notice that after the first licking the mother takes little

notice of the calf for a time. Sometimes, in nature, a cow will eat the

afterbirth. It is not for me to say nature is wrong, but I do say that a

milk cow reared for the byre is not nature, and that the cow should not be

allowed to eat the cleansing. She may choke with it, or suffer digestive

disturbance as a result of a herbivorous animal swallowing a large volume of

quickly putrefying meaty matter.

The main reason for being nervous or exercising

particular care as to the time the cow should be milked after calving is the

possibility of milk fever. High yielding cows are most susceptible, and the

collapse is due to a sudden drop in the lime content of the blood. Some

people think also that high yielding cows on lime-poor land are in greater

danger than if the soil was adequately supplied. The fact remains that a

sudden drawing-off of all the milk in the udder may lower the lime content

of the blood below safety level. Leave the cow alone then for a couple of

hours, and when you come back she will probably have got rid of the

afterbirth. Milk about half a gallon from her—a pint from each teat—not

more, and give it to the calf by means of the finger. Probably the calf will

not take more than a quart, but it is most necessary for the health of the

calf that it should have some of this first milk immediately it is drawn and

before it has had chance to lose its natural heat. Incidentally, that quite

unnatural trick of pushing an egg down the throat of a new-born calf has

nothing to commend it. I find it difficult to imagine how such a custom

arose and what end it was thought would be served. Even in these days of

widely spread scientific knowledge this bit of sleight of hand with an egg

remains a common practice. Give it up, and ensure that the calf gets the

cow's first milk instead.

Another half gallon or a gallon if the cow is a high

yielder, may be drawn six hours later, i.e. eight hours after

calving, and six or eight hours after that the udder may be completely

emptied. The calf may be fed three times a day for the first week and twice

thereafter, though many a good calf has never had more than two feeds a day.

A gallon a day is enough for the first week, rising then to a gallon and a

half, equivalent to 15½ lb. The calf will be ready

to eat a bit of good hay from a fortnight onwards, and after a month, the

milk given will not provide sufficient water for the animal if it is to grow

properly, so fresh water should be offered then each day.

Most crofters will find it cheaper to feed the calf on

whole milk rather than on calf meal and skim milk, until such time as it can

safely go on to skim milk and dry feed. As long after the weaning date of

five months as there may be skim milk to spare, the calf might as well have

it, but one usually finds that once there is a break, the calf will not

touch milk again.

Sometimes a cow is slow to get rid of the afterbirth.

Normally, as I have said, it is dropped within two hours of the calf being

born, but it is quite often eight or twelve hours after, and there is no

need to get worried if she does not cleanse for forty-eight hours. Even then

it is advisable to do nothing drastic until the fifth day, when a washed and

oiled arm may be inserted into the passage and the cleansing gently removed,

place by place, with the thumb and forefinger, where the cleansing is found

to be still clinging to the wall of the womb. This is a job which needs some

practice and skill to do well. If weights are to be hung on that part of the

cleansing which is already to the outside, they should not exceed 4 lb.

altogether, and not hung on until the third day after calving. Undue haste

in trying to remove the afterbirth may result in serious bleeding.

There is now the question of how soon the cow can go out.

Certainly she should not go out until she has cleansed, but after that,

common sense is the best guide. It must always depend on circumstances. If

the day is calm and sunny, even in winter, the cow will not hurt to go out

the day after calving. If there is rain and high wind, even in summer, she

will be best inside, but— and this is a very big but—whether it is summer or

winter, give her plenty of air. Byre doors are always the better of being in

two pieces, and the top half should normally be open unless there is a gale

of wind blowing in and endangering the roof! There is generally too much of

a tendency to coddle a cow after calving, with the result that she does not

get out for a week or more. If you want to coddle a cow, do it from the

inside, as it were, with good food. She can make good use of that sort of

treatment, but standing around in a byre with poor hay and water as a diet

is just melting the flesh off her bones, and most of them cannot spare it.

All the same, a cow should be given a fairly light and

laxative diet for two days after she calves, and not be plied immediately

with a heavy ration of oil cake or a lot of turnips. A few pounds of bruised

oats damped down with some treacle and water, some green stuff such as kale,

and some good hay make an excellent diet for the first two days.

There is a common habit in the West Highlands of keeping

the cows in at night in summer to conserve the manure and perhaps to save

fetching the cows again in the morning. In general, this is a bad habit

because the cow is losing at least eight hours of her grazing time, which

she cannot afford, considering the quality and quantity of food she gets

throughout the year. I often think that if a cow must be kept in for part of

the day, it would be better to be the day time, when cleggs, biting flies

and warbles are distressing the cattle. In the cool of the night it is usual

for the cow to graze. If the cow is kept in and supplied with about

three-quarters of a hundredweight of fresh-cut grass, all well and good, but

to keep her in without plenty of food is undermining her strength for the

winter.

Finally, the cow appreciates a good bed of bracken or

rushes in winter, and you are the gainer with the large quantity of manure

thus got. And she likes a good currycombing and brushing each day. Our

personal gain in this is that she is easier to look at. The milk cow is the

provider of our households, and we are happier ourselves if she is in good

order, comfortable in her bed and clean.