Now that so many plantations are being felled, we might

take the chance of using the slabs which are growing into mountainous heaps

about the country. If these were used as a fence allowing a space between

each slab, they would make a fine windbreak for a few years until cover

could be grown behind them.

42. Growing Cover and Shelter

In a section devoted to the heartbreaking job of growing

cover or shelter belts in a windswept district close to the sea, let me

voice a plea for the care of whatever patches of scrub growth we happen to

have about the township. It always surprises me how different places are in

this respect. Here in Coigach there is no growth of birches, rowans or

willows near the crofts in any of the townships, yet a few miles north of

here there is abundant birch scrub exercising a most beneficial effect on

the crofts. It is so easy to overlook the good things we have and to take

them for granted. Once natural cover has gone it is difficult to replace,

and with the best of good luck it takes several years to grow.

As far as the larger aspect of cover is concerned, it

would be a grand thing if the establishment of shelter belts

could become one of the jobs after the war in the reconstruction of Highland

economy. Such a step would provide work in fencing, draining and planting,

and when the timber had grown less than half its span the belts would be

providing fencing posts and rails for the crofts. I am doubtful whether such

plantings primarily set out for shelter belts would give an economic return

as timber, but their value as an amenity would be incalculable. Obviously,

such shelter belts would not be the task of any individual to establish;

they would be first of all mapped by a committee consisting of

representatives of the township and of the proprietor, and then the expert

opinion of the Forestry Commission might be asked in connection with the

types of trees and shrubs to be used.

The formation of shelter belts round the townships will

take up some of the present common grazing, but it would be well worth it.

The acreage lost could be easily replaced in grazing value by a co-operative

slagging and liming of the common grazing outside the new belts. When the

Border sheep farms were being improved 150 years ago, it was advised that a

twentieth of the whole available grazing should be given up to shelter

belts. We should not need as much as this in the West Highlands for a

considerable acreage of the grazing is at high altitudes where trees would

not grow anyway. Personally, I think a fiftieth of the ground given up to

shelter would be enough. There would be little point here in suggesting how

deep the belts should be, for all such dimensions would need to be reckoned

individually for the places to be planted.

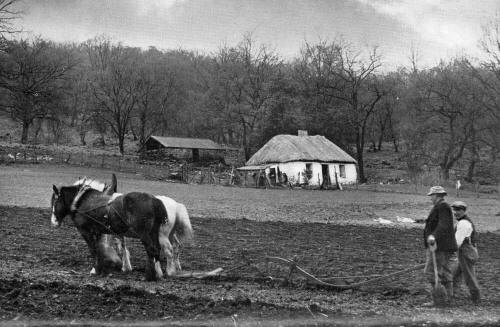

AN ARDGOUR CROFT

Crofters in some of the townships I know in the

Islands and on the outer coasts would think life on such a croft as this

to be a favoured one. Ploughing a good stretch of ground with two horses

(not ponies) and a full-size plough, the natural oak wood providing good

shelter, and a market for all there is to sell only nine miles away. I

have heard crofters say, "I would cut down all that wood and get more

grazing: it's poor timber anyway." Such men have not studied Highland

history and the consequences of removing the timber and scrub from too

much of the ground. Shelter is one of the amenities of life and a fair

proportion of timber means conservation of soil and of beneficial wild

life.

Probably the best tree we have for shelter planting near

the sea is the sitka spruce. It is no good using Norway spruce or Scots pine

because these species scorch badly with spray. Sitkas do well, and it seems

to me now that there is little point in having three rows of mountain pines

on the seaward side because, good as they are at the spray line, sitkas are

equally good. Mountain pines are poor trees and do not live long.

Normally, you do not plant as close as 2 feet apart. Such

closeness would make a forester's hair stand on end, but I believe that is

what we must do when we are planting in the teeth of gales from the

Atlantic. Thinning can be done later, but your shelter must have shelter in

its early stages. The trees to be planted should be young, say

two-year-olds, and short stocky ones at that.

If the stand of sitkas gets going it will be almost

impenetrable at ten or fifteen years old, and of course, there should be no

trimming of the stems to get clean sticks of timber as one would in forestry

practice. It might even be good to cut the crowns off when the trees reach

20 feet in height, for sitkas stand a lot of rough treatment.

In situations where plantations could get started rather

easier, a shelter belt could consist of a greater variety of coniferous

trees, with room left among them for elders and cotoneasters which would

provide bottom growth. However, keep clear of Douglas fir in a very windy

situation; and larch also if there is danger of spray. A shelter belt with a

scrubby bottom growth would hold a lot of summer migrant birds which are a

help to agriculture.

When it comes to growing cover for the west coast of the

Outer Hebrides, I admit myself beaten at present. We should have to start

with a toe of growth such as whin, and build up slightly taller things

behind that. It is indeed a field for research and experiment. Nevertheless,

when one sees some of the trees, hedges of Escallonia and banks of

rhododendrons which occur in some places in the west of Lewis, there is no

reason for despair.

43. Growing Shelter for a Garden

Some day, I hope the problem of growing a shelter hedge

for a garden on the Atlantic seaboard will be tackled on a demonstration

croft run by some institution or the Department of Agriculture, for making

mistakes is an expensive hobby for the individual crofter. I am quite sure

many mistakes will be made before we have reduced the problem to merely

fulfilling a given procedure. As far as I can see, we have no native shrub

that can endure the worst the Atlantic can do and grow to a reasonable

height within a few years. Also, I am quite sure we have not scoured the

world carefully enough to collect all the wind resisters which there must

be.

Here on Tanera our garden is set at the eastern end of a

funnel-like glen and the wind seems to be magnified. I intended to have a

hedge of Cupressus macrocarpa which, I am told, does well near the

sea, but I was advised to use Lawson's cypress instead, as C. macrocarpa

was apt to die back. Well, I lost the lot in the first winter through

the action of a spray-laden east wind, and I am now told that C.

macrocarpa does not die back as long as you do not cut the top off when

it reaches the required height of the hedge. Anyway, my next try was with

hawthorn, and after three years this hedge is certainly growing, but does

not yet provide any shelter. I put some little beeches in with the thorns

but nearly all have died. Both beech and hawthorn require lime, and I

trenched the whole length of my hedge with mortar rubble before planting it.

The thorn hedge would be very unlikely to grow on a peaty soil.

There is another shrub called Escallonia which

makes good hedges in the south-west of Ireland, and it grows on our west

coast too, but my experience has been that it could not withstand March

gales from the east in a really open situation. In any case, the young

plants are expensive.

My greatest hope at present is the large oval-leaved,

blue-flowered Veronica which grows in many gardens on the West

Highland coast as far north as Lochinver. It is a wonderful shrub

originating in New Zealand or Chile, I am not quite sure which, because I

think this West Coast Veronica is a hybrid. It is bright green in

colour all the year round and has smooth fleshy leaves. The flowers seem to

appear at all times, for my own shrubs are hardly ever without blossom. The

shrub grows very close and forms a mass like a half sphere of foliage after

two or three years, when it is 2 feet to 2 feet 6 inches in height. Another

good thing about it is the ease with which cuttings can be struck. We keep

one bush as a kind of stock bush from which we have taken dozens of slips.

These we stick into the ground in autumn, and by spring they are neat little

three-sprigged plants suitable for planting out as a hedge. I reckon that a

really good hedge can be grown in five years in some of our windiest

situations. I have still to determine its range of soil between the two

extremes of peat and shell-sand.

When planting a hedge, prepare the land well beforehand.

Trench it 3 feet wide in autumn, leave it all winter and plant out your

young hedge in late April, thereafter watching that the plants get water

during the dry weather of May and June. Seaweed would be an excellent mulch.

If you can bank up a turf or two along the windward side, such shelter would

help the young plants in their first year. As the hedge grows it should be

pruned back to keep it growing thick. Thorns should be planted 6 inches

apart but Veronica can be a foot apart, and even at that distance

alternate bushes could be removed after two or three years and used

elsewhere. Plant close, however, at first, for the shrubs shelter each

other.

44. Further Thoughts on Shelter

When these sections on growing shelter were appearing as

weekly articles I had many letters on the subject, several asking for

further information and others giving me valuable knowledge based on

experience. It seemed to me the right course was to pass on this knowledge,

for I could have no doubt of the wide interest among crofters in growing

shelter for a garden. And from this very fact I would go the further logical

step and say that if crofters show interest in growing shelter for a garden

they must have a desire to make a garden, and a garden is by definition a

place where you grow things, food plants and flowers; it is not made to

provide a playground for hens—even if these troublesome creatures think so.

Some of these letters asking for further advice on hedges

finished with the entirely practical question, "Where can I get the

necessary plants?" Quite candidly, this was a bit of a poser and emphasized

the lack of attention which has been given to the subject by educational and

official institutions. Several parts of the West Highland coast are

admirable for growing shrubs quickly, yet how many nurseries are there over

here which could set about supplying a demand for shelter species? It is no

good being offered specimen bushes of Escallonia or Veronica

at half a crown or four shillings each; we want quantities of young stuff,

newly rooted cuttings and the like, at a pound or thirty shillings a

hundred. I nearly suggested" in the section on shelter

for a garden that some business-minded crofter with the

right sort of place would do well to start a nursery of Veronica

bushes. Well, I say it in all seriousness now, and if those lairds with

plenty of well-grown hedges or bushes of Escallonia and Veronica

about their policies would be so kind as to take some hundreds or

thousands of cuttings and strike them in some corner of their ground, they

would be doing their fellow-men a good turn and within a year or two make a

reasonable profit.

The cypress originating from a windswept spray-ridden

peninsula in California, known here as Cupressus macrocarpa, is a

very popular hedging plant which I mentioned in my earlier remarks on

shelter. I remarked on its tendency to suddenly die back, especially if

topped too soon. A reader in Argyll who is a keen amateur forester, wrote to

say that this was not his experience, but that the trees do tend to die

eighteen to twenty years after planting if they have been placed too close

to each other. The individual trees must have room enough to develop a

crown. He suggested planting 3 feet apart, the trees being one-year-old or

one-year transplants. C. macrocarpa is a difficult transplanter and

very susceptible to drought when first planted, says my correspondent, so if

possible the young plants should be transferred from pots to avoid root

exposure. Many of the queries I have received have been from the Outer

Isles, and as all plants of this species if used would have to be imported

from the mainland, it would be advisable to take heed of my correspondent's

expert knowledge and buy only C. macrocarpa in pots. The young plants

will be expensive, but at least there will be some expectation of success.

Once again, let me emphasise the necessity of preparing the ground first

where the hedge is to be—digging it deeply first, but my correspondent says

manure should not be dug in for any of the coniferous trees, of which C.

macrocarpa is one. When the plants are in, the surface of the ground may

be mulched with seaweed to conserve the moisture.

My correspondent further said that after the first-year's

growth of the C. macrocarpa hedge, a level top should be aimed at by

nipping off the leaders which grow above the average height. The right shape

of a hedge is one thick at the base and coming more or less to a point at

the top. This shape of a hedge sheds the rain, does not get broken down by

snow, and allows a maximum of light to reach the lower growth.

The same correspondent held out little hope of the

so-called Antarctic beech being any good, an opinion confirmed by another

writer who knew the plant in the Falkland Islands. I understand the plants

are expensive, difficult to obtain and liable to succumb to the variability

of our climate. Cold may not kill a plant, but sudden alternations of

mildness and cold will.

It seems perhaps that I did less than justice to

Escallonia macrantha as a hedging plant for the Islands. Certainly it

does well where exposed to winds from western airts, but from my own

experience and from what I learn from one or two other letters, a gale of

east wind can make it look sick. This shrub grows splendidly from cuttings.

Another correspondent asked me not to forget the humble

willow, and mentions the practice in Strathclyde of planting the

quick-growing withy as a hedge and plaiting the stems as they grow, to form

a sort of living wattle hurdle. This should help to provide the first cover

for a garden. Another plant suitable for exposed situations is the familiar

whin or gorse bush. This does not transplant easily, so should be sown where

it is wished to have the hedge, and in its young stages protected from

stock, which are very fond of the new tender shoots. Nip back the first

leaders to make the plants sprout into a thick, compact, bushy hedge. In

very exposed positions it is a good plan to sow the seed in a shallow trench

so that the young plants get some protection, as is done in the windswept

Falkland Islands.

I forgot to mention earlier the hardy and thorny

qualities of the Worcesterberry, a plant which is a cross between a

gooseberry and black currant. It grows quickly, its thorns will pierce the

hide of the most inquisitive gate-crashing cow, and it produces a good

fruit. To use the words Neil Munro put in the mouth of the fox who ate the

bagpipes, "There's both meat and music in it."

There is also the myroballum plum, a sort of thorny wild

plum which grows very close and becomes impenetrable. Nurserymen usually

have a supply of young plants for hedging. The ground should be dug well

first and lime worked in.

The point I originally made still stands: we need

experimentation in the most windswept Atlantic areas by some educational or

official body which can afford to make mistakes and have some losses in the

search for the right plant or sequence of plants.