32. Choosing our Crops

As winter draws on, seed catalogues begin to appear.

These are good reading for the dark nights if we are working out the

possible cropping of our ground at the same time. Otherwise they are rather

dull. In this and the few following sections I shall talk about growing root

crops and green forage for the cows in winter. It seems to me that our hopes

of prospering in the crofting life do not lie in keeping a few more sheep

and putting a heavier drain on our inbye land by letting the ewes and lambs

graze it late into the spring, but in excluding the sheep from the parks

after February—even if it means keeping fewer—and putting our energies into

growing a good crop of cow feed.

I have already dealt with growing good grass, which we

should look upon as our main arable crop and the maintenance ration of our

cattle stock. You may ask why I have not said something about the oat crop.

Well, I will say something, though it will be rather revolutionary, and will

apply to those areas where threshing of the corn does not take place. Oats

were a necessary crop in the West Highlands while the people were dependent

on threshing and grinding their own oats for meal, but we know now that very

little meal is milled in the West from oats grown on this side of the

country. The oat crop is purely stock feed and in most districts the sheaves

are fed to the cattle unthreshed. The loss of food value is very great, for

many oats are shed, and many more pass right through the cattle without

being digested. Waste in the oat crop can be avoided only by threshing and

crushing the grain.

There is this point too : in our windy, rainy climate an

oat crop has to be thin and short—and practically unprofitable—if it is to

stand up until harvest time. This usually means a rather dirty crop as well

and one which is misery to cut, tie and stook. A really good and thick crop

of oats commonly goes down, and there is another spell of misery in cutting

and tying. I need not dwell on the hazards of harvesting a corn crop in the

West for we are too acutely conscious of them. No, I am coming more and more

to the conclusion that if we can get our arable inbye land into good heart

we should not bother overmuch about corn, but should concentrate on growing

a June crop of hay which will keep the cattle quieter in the byre than

sheaves, and a selection of juicy root and green crops which will last

through till the end of April. There will then be no more cases of cows

getting stomach-fast in the spring through having to subsist on poor hay and

straw with only a few potatoes for juiciness.

I said a selection of roots : there is no need to stick

to green turnips, which are not much good after the new year, or to swedes

which are rather a chancy crop. There are carrots, mangolds, curly kale,

blue cabbage, savoys and drumhead cabbage, all of which are excellent cow

feed, and are in effect dilute concentrates.

Whether we can do much planning of spring crops depends

on our system of tenure. If we have fenced crofts we can please ourselves,

but if the crofts are open and there is a local custom which allows the

sheep to graze over them in winter, it is not possible to grow winter crops

and follow a rotation. Any progress in husbandry is halted. The style of

running the township and the enclosure of crofts is a subject which crofters

will have to discuss in detail some day, for archaic systems need adaptation

in order to meet new situations. There is nothing derogatory in the notion

of change if it is well considered.

33. Turnips, Swedes and Curly Kale

I have visited many crofts on which turnips are not being

grown at all. "Why?" I would ask. "Too much trouble altogether for the crop

we get off," "Lose them every time from finger and toe," "Too much of a

chance," are examples of the answers I have been given. They are sound

enough reasons as far as they go, but perhaps they do not indicate much

effort to get on top of the problem. The root of the matter is that we

cannot expect turnips or any other green crop to grow on land that is worked

out and deficient in lime and phosphates. Once more I am back on this old

trouble, harping again on the need for using some of the shell-sand which we

have on numerous beaches on the Outer Isles and between Cantyre and Gape

Wrath.

As far as turnips are concerned, the most readily

available form of phosphate would be the best, and that is the triple

superphosphate which can now be had in limited quantities. A dressing of 1½

to 2 cwt. to the acre just before sowing would make all the difference to

the crop. Not only would it help the size of the roots, but it would make

them healthier to withstand finger-and-toe. This disease is most obvious in

lime-deficient soils, but some strains of turnips are more resistant than

others. The Bruce purple-top, for example, is highly resistant in a very

lime-deficient soil. This variety deserves to be better known in the West.

There is also the Wallace green-top turnip, and a highly resistant swede is

the Danish variety known as Wilhelmsburger. Turnips, of course, need muck

and plenty of it, though the West-coast practice of sowing them on newly

turned lea is a good one if the ploughing has been a first-class job.

Otherwise the hoeing will beat you.

Swedes are even more dependent on phosphates for

satisfactory growth than turnips. Where the land is in good heart, swedes

should be preferred to turnips on a West Highland croft. They grow a bigger

crop, contain more nutrients, are sweeter and last longer into the spring

than turnips. Also, a swede is a grand thing on your own table, boiled and

mashed, and with butter, pepper and salt. But they will not put up with such

late sowing as turnips.

Preparing a tilth for the root crop, carting out the

manure and sowing the seed make for concentrated work just at the time one

has to be at the peats. My own practice has been to spread the work of the

root crop throughout the months of April and May in order that I should have

time for other things. This has been made possible by using several kinds of

plants. First, curly kale ; I sow the seeds in September in a bit of shelter

from the wind and transplant in early April on to well-mucked, well-firmed

ground. This heavy-yielding green crop stands up to autumn and winter gales

where flat-leaved kales would be withered. A crop of leaves is ready to

break off for use from August on to November. The stems and crowns of the

plants should be left intact. They will sprout again in spring and give a

wealth of green food in April and May when we are so short of grass. It is

not much good sowing the curly kale in spring for a crop that year. The

stalk is too spindly, the crop not big enough, and it does not sprout so

strongly again in spring. And let me repeat, if you want bulk in the crop

you must do it well and have the soil well balanced.

34. Carrots

Continuing the idea I have put forward of spreading the

work of the root sowing time which so often coincides with that other

necessary job of cutting peats, I suggest that carrots should have a place

in the root break wherever they can be grown without the probability of

their being attacked by the fly. The advantages of growing some carrots as

stock feed in a crofting husbandry are as follows:

1. They are sown earlier than other root vegetables, that

is, at the end of March or during the first week in April; but if one does

get a bit behindhand, they can still be sown up to the end of April. I

usually sow my carrot seed between 1st and 10th April.

2. The ground, though it must be deeply worked and in

first-class heart, is very easily prepared for carrots, because there should

be no manuring with farmyard manure for this crop. Suppose you have a bit of

ground that was heavily manured for potatoes: if it is not too stony it will

do well for carrots in the following year. Digging the potato crop will have

in effect given the soil an autumn digging and the potatoes should have

helped to clean it. In March, then, all that that ground needs is digging

over and harrowing down to a fine tilth. It should then be firmed by rolling

or treading along the rows where the seed is to be sown. I sow my carrots in

drills 15 inches apart, making the drills with a bit of stick drawn along a

line. The seed should be sown thinly with the thumb and forefinger, then the

drill is lightly covered with the back of the hand or a bit of slate and

well trodden with your right foot as you go along the row. About 5 lb. of

seed to the acre are required.

Field carrots are usually of the white variety and can be

heavy yielders, but I never grow that kind as half the beauty of the crop

would seem to be lost. I prefer James's Intermediate, and I can think of no

part of the West Highlands where another variety would be preferable to this

excellent kind. There is also no difficulty in getting seed.

3. Carrots give you a bonus or dividend during their

growing period. Singling begins during the second week in June, at which

time plants should be thinned to 1 inch apart. If carrot fly is in the

neighbourhood the ground should be well firmed round the remaining plants

after singling. Incidentally, the fly is less troublesome in windy

situations than in sheltered glens. A second singling can be made from July

on into August. This time the carrots are of nice size and most acceptable

on one's own table, or they can be sold very readily at a good price—say 2d.

to 3d. per lb. The final singling should leave the plants 2½

to 3 inches apart. The crop should be carefully cleaned while the tops make

it still possible.

4. I have found carrots growing under island conditions

to give me a heavier weight of roots per acre than either turnips or swedes.

After all, the rows are much nearer together and so are the plants. Last

year's crop yielded at the rate of 30 tons to the acre, and I think this

year's will be almost as good. This is about twice the yield of field

carrots grown on a commercial scale.

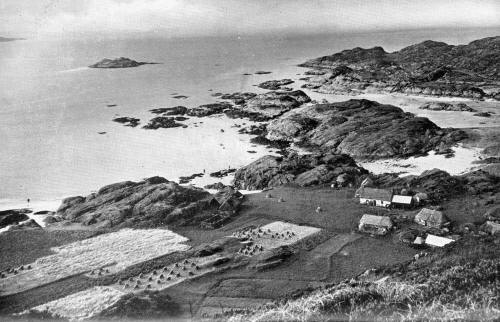

CROFTS AT ARDTOE, MOIDART

If they can be adequately fenced, crofts like these

can be among the most desirable on the West Coast. These pockets of soil

among the rocks can be raised to a very high level of fertility, and the

nearness to the sea makes for earliness and a plentiful supply of

seaware—and in this place, shell sand. Two acres here could grow as much

as four in many a croft farther inland. The crofts must be fenced,

however, if they are to be worked on a rotation which will enable winter

feeding crops to be grown. This ground would grow early potatoes.

5. Carrots contain 13 per cent. of dry matter compared

with 10.5 per cent. in turnips and 11.5 per cent. in swedes. Therefore, even

rather a lesser crop of carrots than of turnips, weight for weight, will

still give as much value in feeding power. The carrot contains a valuable

substance called carotene which is a constituent of young grass and the

forerunner of Vitamin A. Carotene in the cow's body helps to maintain the

yellow colour of the butter-fat.

6. Carrots keep well. In our West Highland climate I

leave my crop in the ground all the winter, digging it as I need it for both

ourselves and the cattle. There is no better root feed for cows in those

hard days of March and April and the cows are particularly fond of ''

carrots.

35. Mangolds

There is too much of a tendency for people to think

inflexibly of north and south in relation to where crops can be grown. In

many ways it would be more sensible to think in terms of east and west : for

example, good wheat has been grown in Orkney this year, but none has been or

would be grown in Mull, nearly 300 miles farther south ; similarly, given

equal fertility of the soil, a field of rotation grass in Mull would be

easier established and would give a bigger crop than in East Anglia 300

miles south again.

The mangold has been considered in that rule of thumb

fashion—that it does well in England on good land and is not suited to

northern upland conditions. But let us think what the mangold is, what its

limitations are and what our West Highland climate has to offer. The mangold

is descended from the wild sea-beet, a plant of the seashore. Our crofts are

nearly all near the sea and many of them almost at sea level, and little

troubled by frost. In England mangolds have to be lifted early to prevent

frost catching them while still on the ground or newly pulled. We have the

advantage then, on this point. I have left some of my mangolds out as an

experiment and find that while still growing in winter time, they will stand

10° F. of frost.

These valuable roots grow to much larger size than

turnips or swedes and contain a higher percentage of dry matter—12.5 per

cent., of which a goodly portion is sugar. They are not ripe before the New

Year and should not be fed until then. In our West Highland climate the crop

need not be lifted before the end of November or early December anyway.

Mangolds are a long-keeping root, so (always assuming you have enough of

them) they can be fed to the cows as late as May. Being almost devoid of

carotene, the butter of cows fed on them is very white, but if you have

grown carrots as well, a mixture of the two roots makes excellent cow feed.

Mangolds cannot stand starvation. If they are to be a

profitable crop they must be well done, and for that reason I recommend them

only to those crofters who have ground of fair depth in good heart and who

can give a good dressing of seaweed or dung. That is another point; as the

plant is descended from the sea-beet, it responds excellently to seaweed and

it likes a fair amount of salt. My own practice is to make a compost of

seaweed and farmyard manure.

Heavy crops repay good care : the manure should be spread

in early March and ploughed in. Sowing should take place at the end of April

or in the first week of May. Mangold seed is like beet seed, and if you have

no seed drill, the seeds should be sown by hand in shallow drills on the

flat, about an inch between each seed. Because I have no horse labour, I

make my rows only 2 feet apart or even 21 inches. The seed has a hard outer

coat, so it helps germination to soak it in water twenty-four hours before

sowing.

The young plants when established withstand drought very

much better than turnips and they do not suffer from diseases such as

finger-and-toe. The plants should be singled to 10 inches and the ground

kept very clean.

A very light sprinkling of nitro-chalk along the rows

would be a helpful top dressing at this time. Too heavy manuring with

nitrogen will make the plants bolt, and that means lower yield and poorer

keeping quality.

Mangolds need care at lifting : a good inch of top should

be left on them and the roots should not be tailed at all or they will bleed

and that will hasten decay. Do not follow the lazy man's way with turnips,

of loading them into the cart with a fork. Make the clamp frost-proof. The

tops can be fed to the cows.

I have now tried four varieties of mangolds— mammoth

longs, red intermediates, and yellow and orange globes, and have found by

far the best variety for our climate is the red intermediate. This yielded

at the rate of 45 tons per acre in 1942 (the pity was I had only a quarter

acre !) and will give me about 35 tons per acre this year.

To sum up this plan for the root break: you can arrange

for the root sowings to be spread over six weeks in the spring with the

consequent singlings spread out as well. You get a variety of crops which

can be fed from September to the middle of May and will keep an

autumn-calved cow in milk throughout the winter season.