49. The Constituents of Food

Food looms big in the lives of all of us. The men folk

may do no more than spend an hour or two during the day eating, but women

spend many hours of the day getting it ready to be eaten, and it is one of

their perpetual remarks of surprise that what takes so long to prepare is so

soon eaten. Men may not be bothered so much about their own food but on them

rests most of the responsibility for growing the food which their animals

eat, and that can be a considerable nervous as well as physical strain. Men

have to till the ground and feed the plant which will in turn feed the cow

which will help feed the family. Much of what I have written in this book

has dealt with getting conditions right for the plant to feed and suggesting

the foods the plants need. A chapter on feeding the animals with what we

have grown on the croft may be useful.

CROFTS AT BREASCLEIT, LOCH ROAG, LEWIS

This photograph vividly shows the strip crofts which

are so common in Lewis. A croft may be no more than a few yards wide and

the best part of a mile long. There may be a ditch or a balk between

each croft. The crofts are laid open for grazing each October until

March. Such a system precludes the growth of winter fodder crops, and

cultivation of such narrow strips cannot be done economically. As this

picture shows, small enclosures by fencing are taking place, and we may

expect to see enclosure of crofts become general in time to come, or, in

such places where the stretches of arable ground are sufficiently large,

the whole township may come to do away with the wasteful ditches and

balks and run the arable ground as a collective farm on which machinery

could be used instead of the spade. This would give the crofter time to

engage in other activities.

There is one big difference between feeding plants and

animals: plants can take their food only in the form of mineral salts which

are soluble in water or weak acids—lime as calcium carbonate, nitrogen as

calcium nitrate, and several other elements in the form of salts. The big

four, we found, were lime, nitrates, phosphates and potash. Even when an

organic manure such as dung is applied to the soil (organic meaning that

complex chemical state of a substance derived from the animal or vegetable

kingdoms) the plant must wait until bacteria have broken down the dung into

mineral salts before it can feed. Animals, on the other hand,

must have their food in organic state, consisting of plant or animal matter.

They cannot feed on mineral salts alone. Yet both plants and animals are

needing precisely the same elements—calcium, phosphorus, nitrogen,

potassium, and so on. The difference in the food is in the chemical

constitution. Organic food has these elements bound up with carbon, hydrogen

and oxygen; carbon and oxygen coming originally from the air, and hydrogen

and oxygen from water. It is the particular feat of life of the plant to

create starch and sugar from air and water, through the agency of light. The

process is called photosynthesis, a word of Greek derivation meaning

combining through light. This is why we grow potatoes. This plant can

manufacture starch through the leaves and store it in the tubers in

convenient form cheaper than the modern chemist can make it in a laboratory.

The sugar beet will make sugar cheaper than the chemist can. These organic

compounds of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen are collectively called

carbohydrates and are one of the three main groups of foods necessary for

the animal. You may prefer to think of them as starchy-sugary foods.

Mother Nature is a remarkable woman, if you will allow me

to personify the workings of the cosmos, and employs excellent warehouse

practice. Some of her plants make such a lot of carbohydrate matter that

some form of concentration is necessary: she turns it into oils or fats,

which are nothing more than a complicated and special group of compounds of

carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. The animal is unable to digest sufficient

starchy-sugary food to fulfil its needs, so some of its intake of C, H and O

is in the form of fat. When animals store these elements in their bodies,

they store them as fat of rather more complicated structure than the oils of

plants.

Where does the nitrogen come in and the phosphorus? These

elements are found joined up organically with C, H, O, sulphur and other

elements, in a highly complex way, and we call such substances proteins,

being derived from protoplasm or living substance. Animal proteins are more

complex than vegetable ones and usually of more concentrated feeding value.

These are the three big groups of animal foods—the

starchy or carbohydrate, the fatty, and the meaty or protein. Unless animals

receive them in sufficient quantity, in right proportion and in digestible

form, there is trouble or at least a grave loss of efficiency.

In addition to the three groups of carbohydrates, fats

and proteins, which make up the bulk of food for man or beast, there are two

others which are equally necessary, but in very small quantities—mineral

substances and vitamins. Unless they are present the animal system cannot

make efficient use of the rest of its food.

If conditions are perfect there are sufficient mineral

salts of calcium, phosphorus, iron, copper, manganese, cobalt, sodium and so

on in the food as it is produced from the ground. But we do not live in a

perfect world. If the ground is lacking in these minerals, the plants

growing on that ground are going to be deficient also and the cattle and

sheep we feed are going to show it. West Highland soils are frequently poor

in one or more essential minerals, so in addition to doing all we can in

manuring the ground it may be necessary in addition to give the animals a

special ration of mineral salts. They are conveniently given in the form of

bricks of mineral "lick" placed in a container in front of the cow in her

stall. Many (I might say most) cattle and sheep in the West Highlands show

the need of lime and phosphorus, and in Tiree we have an example of another

mineral-deficiency disease known as pining, caused by a lack of cobalt in

the pastures overlying shell-sand. Yet the animal needs only about one part

of cobalt in two million in its food. Rock salt itself is a great help to

stock, but it should not be thought to fulfil the whole of an animal's

mineral needs.

Some types of stock need special mineral feeding if they

are to do their best : for example, a heavy yielding cow needs more calcium

phosphate than she can normally get from her food, and young pigs at weaning

time may get into a sorry state through an insufficiency of iron, a

substance which can quite easily be put into their ration. It is a pity to

spoil the ship for this most important "ha'porth of tar." Crofters

throughout the Highlands would do well to offer their cattle a mineral brick

to lick.

Vitamins, or accessory food factors, have no feeding

value in themselves, but the presence in the food of minute quantities of

these complex chemical substances is necessary if the animal is to remain in

good health. For convenience, vitamins are labelled A, B, C, and so on up to

K. Probably new ones still remain to be discovered. When a cow is at pasture

it is unlikely that she will be short of vitamins, but if she is living

inside in winter with poor hay as the staple diet, she will probably be

vitamin-starved and her milk will not have the same healthful qualities it

had in summer.

Vitamin A helps an animal to keep clear of infections. A

deficiency of it is shown by sore eyes and chronic sore throats and

cessation of growth. It occurs in green foods, carrots, fish oils and in

most seeds and cereal grains.

Vitamin B contains several substances, not all of which

have been isolated by chemists as yet. A deficiency of Vitamin B results in

nervous disorders and paralysis. It is not normally in short supply in a

cow's ordinary diet, but chickens may suffer under some circumstances.

Vitamin C prevents scurvy, but it is of little or no

importance to the cow as far as can be ascertained. It is present in fruits

and vegetables and is of great consequence to our own health. Vitamin C does

not occur in cereal grains until they sprout.

Vitamin D is important to man and his domesticated

animals. Deficiency of it results in rickets and means that the animal

cannot take from its food and use the calcium and phosphorus necessary to

build healthy bones. It is often shown to be deficient in the diet of

poultry by the number of thin-shelled eggs laid. When animals get plenty of

sunlight they manufacture their own Vitamin D. It occurs in some fish oils,

particularly the liver oil of cod, halibut, and some sharks which live on

other animals which eat the life of the surface layers of the sea, which

animals live on the microscopic floating plants which collect the sunlight.

The other vitamins are not of much importance in ordinary

stock-feeding practice.

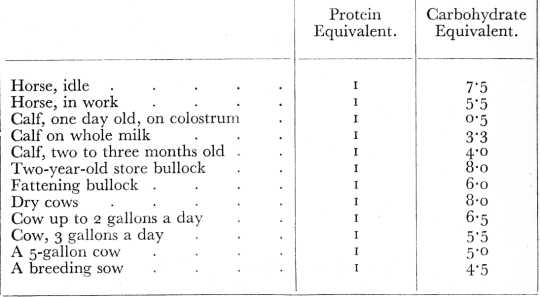

50. The Nutritive Proportions of Food

USING THE CAS-CHROM IN SOUTH UIST

Hark work seems to be accepted in the right

philosophical spirit by our friend in the photograph. He is making

lazy-beds for potatoes by turning the turf on to strips of bladder wrack

already laid down. His cas-chrom has a longer blade than most

mainland types in use at present. After personal experience of trying to

plough in ground strewn with glacial boulders, I think it is better to

work the ground like this. Unfortunately, I was never able to develop

the knack and speed with the cas-chrom which makes this tool

still a useful one even in 1945. Hard work, whether in man or beast,

needs right feeding of a balanced ration.

A thorough knowledge of the contents of feeding stuffs is

a chemist's job. The man who has to feed animals can concern himself with

little more than knowing the percentage of the three main groups of protein,

fat and carbohydrate present, and keeping in mind the mineral and vitamin

contents if any. The feeder of animals must also learn how to compound

various foods which he has at his disposal to make up a balanced ration. In

our own dietary we find by experience that we must not eat too much meat or

try to live on oatmeal without milk; we know that our bread needs butter.

When I hear that in days gone by an Outer Isles fisherman when out in the

boat would put a fish's liver inside a split girdle scone, sit on it to

squeeze the oil from the liver into the scone, and then eat the soaked

scone, I take my hat off to him as to a professor of dietetics. Similarly, I

have heard of a Hebridean who kept a jam jar of chopped fish livers at the

side of the stove, into which jar he would dip his oatcake at mealtimes when

butter was short. These men knew.

In addition to knowing the right proportions of proteins,

fat and carbohydrate to include in a beast's ration, we have to keep in mind

one other important matter, the digestibility of the food, and its

counterpart, the quantity of actual dry matter the animal can deal with in a

day. If you want to understand how to compound rations from your available

feeding stuffs and are able to supply a balanced ration, your cattle will

come through the winter in good order. At present it is safe to say that 75

per cent. of the cattle in the Highlands suffer some degree of starvation in

the winter —my own included, at present, for we cannot grow enough high

protein food in the West nor can we buy enough in wartime. All the same,

even when we could buy the food and had the wherewithal to buy it, lack of

knowledge of compounding rations resulted in much wrong feeding.

There is no simple, easy way of learning the theory of

feeding. It needs application, hard learning and some knowledge of

chemistry. Similarly, it cannot be explained in the space of a few lines.

The modern method of compounding a ration is to use a figure called the

starch equivalent, that is, all foods are reduced to terms of starch for

purposes of calculation. But it is not easy. An older and simpler method is

that based on what was called the "nutritive or albuminoid ratio," which may

be clearer to anyone unable to attend lectures or an agricultural college.

Albuminoid means protein, and the ratio is intended to indicate the right

proportion of meaty stuff to fatty and starchy stuff in a ration. It will be

obvious that a young calf or a cow in full milk or a horse in heavy work

will need more protein than a two-year-old bullock or an idle horse.

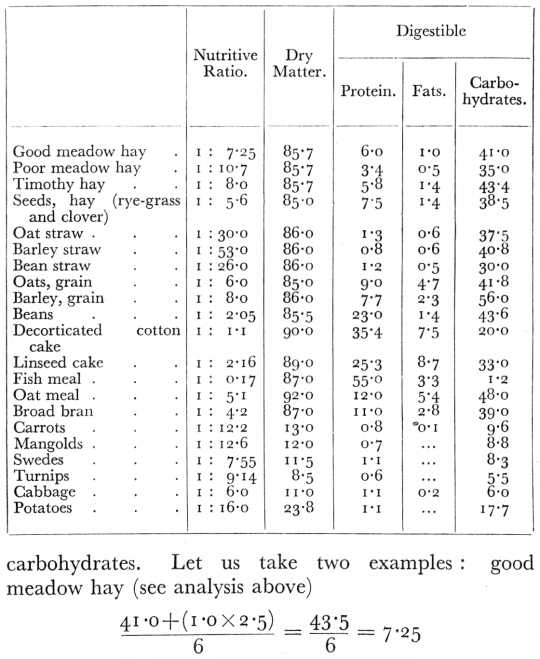

Here are a few reasonable nutritive ratios for different

classes of stock:—

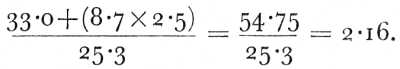

51. The Nutritive Ratio in Practice

It would not be economical of space to give a long list

of the composition of the many feeding stuffs available to the farmer and

crofter in peace time. Such a list may be obtained in a Ministry of

Agriculture Bulletin obtainable from H.M. Stationery Office. Here are a few

analyses per cent. of the foods a crofter might have now. Even of some of

these he has probably seen none for a long time, but this list will give a

fair idea of the relative values of common foods for various classes of

stock.

The nutritive ratio is calculated in this way: as the fat

is of higher feeding value than carbohydrates the percentage is multiplied

by 2.5 and added to the percentage of digestible carbohydrates. Then the

percentage digestible protein is divided into this sum of fat and

The nutritive ratio is 1 : 7.25 (from which we see it is

a good enough feed for dry cows and two-year old bullocks but is not

"strong" enough for a milk cow or a horse in heavy work).

Linseed cake

The nutritive ratio is 1 : 2.16, too strong a feed alone

for any stock.

The rest of the nutritive ratios of the foods shown above

are given to save you the trouble of working them out.

Perhaps the more modern factor for multiplying the fat to

show its equivalent as carbohydrate would be 2.3, but the difference would

be very small in the figures I have given.

From the figures I gave in the last section it will be

seen that rations for the general run of livestock should vary in nutritive

ratio between 1 : 4 and 1 :

8. If you feed a store bullock on a ration with a nutritive ratio of

1 : 5 you are being extravagant, and a cow fed on a ration giving a ratio of

1 : 8 is being starved.

52. Compounding a Ration

The problem now remains to compound a ration and find its

nutritive ratio from the foods of which we know the ratio already.

Suppose we have good hay this year and but little else

except a few turnips and crushed oats, so that we might find ourselves

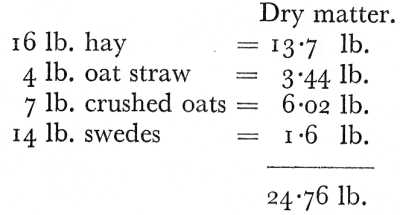

unable to offer a small milk cow more than the following ration per day:

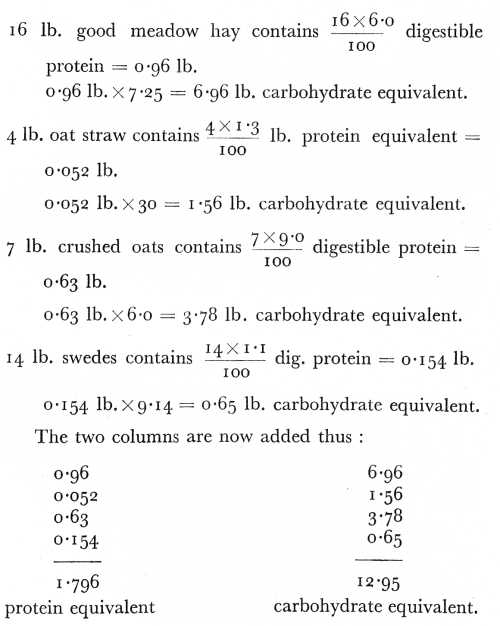

By taking each food in turn, we find out the amount of

digestible protein we are giving by multiplying the number of pounds by the

percentage of digestible protein and dividing by 100. The figure obtained is

multiplied by the nutritive ratio, which gives us the amount of digestible

carbohydrate equivalent. Here we are:

The nutritive ratio, then, of this ration is as 1.796 is

to 12.95, that is, 1 : 7.2. By reference to the table given in Section 50

this ration is not quite good enough in quality for a cow giving up

to two gallons a day. It would be corrected by that pound or two of linseed

or other oil cake which we cannot get just now

Let us look at the quantity. We found the ration

contained 24.76 lb. dry matter. Estimation of total bulk of food given to

stock is of great importance. Cattle, for example, must have sufficient

roughage or they cannot chew the cud satisfactorily. Animals are not

satisfied with tabloid food any more than men are. Equally, there is a limit

to the quantity of food with which an animal can deal, and its requirements

of protein and carbohydrate equivalents must be contained within a

well-defined quantity. And here, also, we begin to split our ration into two

parts in our minds—that part needed for maintaining the animal in its

present condition without any production of work or milk, and that part

concerned with production for which we keep the animal. Our cow needs for

maintenance purposes

1.5 per cent. of her weight in dry matter each day, and

about 1.0 to 1.5 per cent. for production—say,

2.75