It is certainly possible to grow plants without soil as

long as the water in which their roots live is supplied with the right

amounts of the many mineral salts they need. But for all ordinary purposes

the soil is the medium in which our crops must grow. If that soil is not in

good heart itself, an addition of manures in the form of mineral salts will

not result in a good crop.

The soil is not just a collection of particles of sand

and silt and clay but a living world in which the processes of change are

going on all the time. The livelier we can maintain these processes by

cultivation, the more plant food will be made available, and conditions are

set fair for higher yields. For example, there is no better general

fertilizer than farmyard manure, yet very little of it can be used directly

by the plant, whether potato or a grass seeds mixture. Decomposition of the

dung to simpler substances must take place and the quicker this occurs the

sooner will the crop go ahead. This breaking down of manure and of part of

the soil to form plant food is largely brought about by germs which live

naturally in the ground.

The soil needs air to allow it to crumble to a good tilth

and the germs need air to help them convert the manure. We get that air into

the soil by ploughing and cultivating, but better still by digging. The deep

thoroughness of the spade is one reason for the greater fertility of a

garden compared with a field. There is no doubt that where the use of the

cas-chrom still continues

better crops are grown than by horse ploughing. In the

old days in the Highlands the crofter was doing in effect what I was

suggesting on p. 2 as being sound policy, namely, treating his arable ground

intensively. He did a bit of ground well and got a crop. Not only did he get

a higher yield in one year, but he was building up his ground, making

capital for the future.

The soil cannot get its air if it is waterlogged, so

draining is one of the first necessities. If the arable ground is in a glen,

some open drains may be necessary to carry off the water which rapidly seeps

down from the hill after heavy rain. Water lying in the soil means a

stoppage of those processes of change, a coldness and lateness for plant

growth, and conditions are such as to encourage the formation of an acid,

rubbery, peat-like soil which is most difficult to work even when dry. When

I was on North Rona I observed the soil of the lazy-beds which have not been

worked for over 200 years. Its good quality is still apparent, compared with

that part which was never tilled. The ground was well drained and the soil

deep and there was not a rush or a docken in it. In summer time those

lazy-beds are covered with wild white clover, testifying to the goodness and

health of soil well tilled by a folk long since gone. These fertile

lazy-beds or feannagan are their lasting monument.

2. The Soil as a Sponge

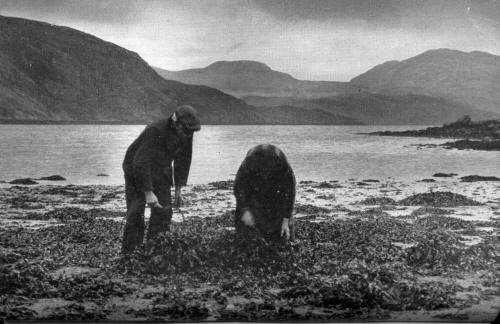

LAZY-BEDS IN THE MAKING, SOUTH UIST

This is one of the few places where new lazy-beds are

still being made. Feannagan take up a lot of ground, but they are

a good form of husbandry on peaty ground where drainage is difficult.

Draining tiles are no good in peat, for peat is like a jelly and dries

best with open drains at close intervals.

Those East-Coasters who sometimes express the view—on

insufficient observation and through lack of understanding—that

West-Coasters are lazy, might take a good look at this picture. It

needed a lot of hard labour to get the seaware so neatly laid out on the

ground, and it needs a big heart to tackle the digging by hand of this

area in the short time before the potatoes must be in.

The West Highland climate is reckoned a wet one, and as

much of the ground is peaty, a waterlogged condition is commonly found which

exercises us principally towards getting it well drained. Quite apart from

the actual drains we may dig, cultivation and liming are also aids to good

drainage. But there is the other side of the picture as well—how far can our

arable ground withstand the spring droughts ? Peat is a wonderful

water-holding substance, useless for growing corn and root crops, but found

so often alongside our strips of arable land which tend to dry out between

March and June. The peat consists of decayed vegetable matter of a sour,

acid kind, which for all practical purposes is like a jelly. Much of our

Highland arable land, on the other hand, has lost some of its decayed

vegetable matter and has become little more than a mixture of particles of

rock. Such a soil lets water pass through it quickly, though some

deep-rooting plants may get below this sandy layer. If the soil is shallow,

overlying rock, no plant but a quick-growing annual weed gets a chance to

survive.

These thin, light soils of the West have little buffering

power such as we should find in the clay soils of a large part of England.

They have the advantage, however, of being easy to work; they are often

early and can be worked almost immediately after heavy rain. But they cannot

grow a good crop unless their buffering power of holding water and of

holding manures is built up and maintained.

We can attain this end by liberal use of farmyard manure,

which in addition to supplying manurial elements gives body to a soil.

Rotted farmyard manure in the soil forms a substance called humus, which may

be looked upon as being the sponge of the soil. It is difficult to get

enough of this non-acid humus into the soil, but there are ways and means if

we use our ingenuity. There is no doubt that we need to keep more cattle if

only for their value as agricultural implements and manure makers. When

housing cattle in winter it is worth while getting as much waste vegetable

matter into the manure heap as possible. For example, I recently saw a great

heap of rushes tipped on to the rocks at the seaward edge of a croft; this

was a waste. Rushes are well worth while stacking for bedding with a view to

enlarging the manure pile. They do not rot in the heap as easily as straw,

though the process can be hastened by mixing occasional layers of seaweed

with the manure. Still another means of providing humus is the. short ley,

but if the ley is to play its full part it needs careful management and the

help of cattle in grazing and dunging it. It is a subject we shall discuss

later.

3. A Balanced Soil

The strength of a chain is that of its weakest link, we

firmly believe, but to apply this philosophy to the fertility of the soil

where it is of immense importance, we must find a different comparison. A

barrel has a number of staves of equal height and will hold water to the

height of the staves. Let us liken our soil to the barrel and the crop to

the quantity of liquid the barrel will hold. The staves of the barrel

represent the several conditions which are necessary for plant growth—

sufficient water supply, sufficient air, suitable temperature, enough plant

food in the form of nutrient salts, plenty of room for the roots and absence

of injurious substances. Our barrel has these six main staves, but some of

them, such as the sufficiency of nutrient salts, are themselves made up of

several strips of the fabric of the barrel.

A well-balanced soil is like the complete barrel; it will

hold water to the limit of its capacity because every stave is sound. Such

cultivation as we give that soil would be the equivalent of holding the

barrel upright so that it would hold to capacity. Now supposing our barrel

gets a dunt which breaks off one stave a foot from the top. Its capacity is

reduced for it will not hold water above the height of the broken stave. We

get no comfort from assuring ourselves that the other staves are perfectly

good. And if, again, someone bores a hole in another stave near the bottom

of the barrel, the accident to the first stave will lose all significance

until the hole is bunged up, because the barrel will not hold water above

that point. If one strip of the stave called nutrient salts is missing or

short, we are still going to lose the possibility of a full barrel.

Similarly with our soil; it is no good our saying it is

well manured and all the rest of it if the soil is short of air as a result

of bad drainage. The plant roots breathe a lot of air and the amount they

get is closely linked with the quantity of plant nutrients they can then

absorb. Sufficiency of air in the soil is the result of good drainage and

cultivation.

It is no good draining and cultivating, either, if we

then starve the crop of manure. The whole skill of husbandry is in judging

the capacity of our barrel and keeping all the staves to their full height.

The barrel will hold no more if we add a bit more to one stave, or even five

staves. It would be just a waste of time and money.

When I see a man working hard on a piece of ground that

is obviously short of lime and phosphates, I feel sorry, because I know he

is wasting part of his labour, just as if he was trying to fill the barrel

with water by pouring in pailful after pailful, when one stave was broken.

We have to judge the condition of the soil as we would that of the barrel,

and if such judgment is a bit beyond our powers we can call in the soil

expert just as we would get a cooper to repair the barrel. This service is

provided by the Colleges of Agriculture.

4. Cultivation and the Unseen Life of the Soil

If a piece of land gets so dirty with twitch that it has

to be raked over and the twitch gathered, it may be noticed that if the

rubbish is burnt on one big fire which is kept going for a considerable

time, the ground underneath loses its blackness and becomes red. And in the

following year you will find that bit of ground barren where the fire was.

The reason for this is that the soil has been sterilized : all the minute,

single-celled animals are killed and, what is more important, all the

bacteria or single-celled plants are killed also, all the millions and

millions of them which are present in every handful of soil. Without these

bacteria the soil] is worthless for growing plants of agricultural value.

What then do the bacteria do, and how can we help them, so that, in their

turn, they can help us?

When we burnt that twitch we noticed the soil beneath had

turned from black to red. The blackness of the soil indicates that it is

rich in rotted animal and vegetable matter, shortly and collectively called

humus. Humus, as I have explained already, enables the soil to act as a

sponge, keeping it open enough to drain, and yet allowing it to hold water

in dry times. The burning of the twitch burnt the humus in the soil beneath

as well, the humus which was the home of all those little Robin Goodfellows,

the soil bacteria.

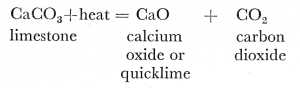

CUTTING SEAWEED

Seaware is in the news and appears likely to become

the raw material of a considerable industry. The crofter may usefully

supplement his cash income by gathering the stalks of tangle for this

new industry. Happily, it is well recognized that the natural harvest of

weed on the beaches is also one of the raw materials of crofting

agriculture and a most necessary one, for it provides organic matter to

be transformed into humus in the soil.

Our old friends on the shores of Loch Seaforth have

no tangle to cut as have their relations on the western side of the

Isles or in more seaward places. They are gathering wrack and the

condition of the beach indicates that cutting has been regular, for

there is no great wealth of weed. We can imagine an outsider viewing

this scene and exclaiming "Uneconomic!" It may be, but for myself it was

a job I enjoyed in my island years: the smell of the weed was good and

there were interesting things to see among the weed. If we can live and

enjoy, then life is good.

The most important groups of soil bacteria concerned in

breaking down waste animal and vegetable matter so that it can be turned

into plant food, need air just as we do in order to live and work. We aerate

the soil by draining it and by our annual cultivations which expose it, turn

it over and leave it light. The drainage allows the soil to become warmer;

the bacteria work better in warmer soil and produce more humus, which makes

the soil black; and a black soil absorbs more heat from the sun so that the

bacteria can work harder at breaking down the animal and vegetable waste or

organic matter, and the warmer black soil grows crops better and ripens them

quicker. The man of sense does not forget his unseen helpers in the soil; he

keeps his drains open and gives his ground more than a scratch over once a

year.

There is one other necessary condition for the bacteria

to work well—that the soil should not be too acid. The addition of lime

neutralizes the acidity and provides a chemical base, calcium, with which

the nitrogenous part of the products of the bacteria can combine to form a

plant food such as calcium nitrate.

This is one of the great everlasting processes going on

in the soil and is called by the agricultural scientist nitrification. We

dig farmyard manure, fish guts, seaweed and plant roots into the soil ; the

bacteria attack them all and break them down into humus. Then the humus is

still further broken down till the nitrogenous portion becomes ammonia ;

whereupon it is seized by yet another group of bacteria which turn the

ammonia into nitrous acid. This stage is an extremely short one, for the

nitrous acid combines with the calcium base to form a nitrite, after which a

final group of bacterial workmen turn it into calcium nitrate, which

substance is available to the plant. The whole thing is like the reverse of

an assembly line in a factory. The organic matter comes in raw and a

succession of specialist bacteria split it and deal with the subsequent

products, until it is rendered available again as pure plant food.

5. The Value of Lime

When I think of the fact that man was liming his ground

in prehistoric times, I am struck anew by his inborn capacity to observe,

and to act rightly on the evidence of his eyes. Lime is an essential plant

food and together with phosphorus is the main constituent of bone, but it is

not one of those manures which give a spectacular increase of plant growth

shortly after application. On heavy land, the most important part lime may

play is in making the soil more workable and easier drained. It also has the

effect of helping to clean ground of parasites if it is applied in the newly

burnt state.

The shortage of lime and phosphates in the soil makes it

necessary to send our hoggs down country for wintering. It is an expensive

business and wasteful of condition to take flesh and blood all those miles

when the greater benefit would follow from bringing lime to the crofts. Our

West Highland agriculture is limited in its possibilities by this shortage

of lime and phosphates. We cannot manure our ground heavily to take off big

crops unless the lime level is right. It is no exaggeration to say that a

period of economic prosperity could follow a good liming of all our arable

ground. That would be a large undertaking which we are unlikely to see

fulfilled in wartime, but many of us are in a position to do more in the way

of liming than we do at present.

There seems to be a good deal of misunderstanding as to

the value of various forms of lime. Let us try to understand what lime is :

the essential constituent is the metal element calcium, but this substance

does not occur alone. It is chemically combined with carbon (charcoal and

lamp black are examples of carbon) and oxygen (the gas which forms one-fifth

of the air we breathe). Limestone, chalk, coral and shell sand are all forms

of calcium carbonate. Now if these substances are subjected to great heat,

the carbon and some of the oxygen are driven off in the form of carbon

dioxide, the gas which forms one twenty-fifth of the air and which makes the

fizz in soda-water. The calcium and some oxygen are left. If we call calcium

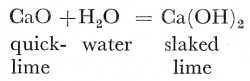

Ca, carbon C and oxygen O, the result of burning limestone may be

represented thus:—

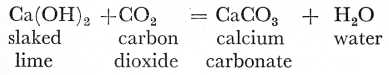

We all know that quicklime is unsteady stuff; the steamer

will not carry it except in barrels, and if it is left in a sack in a damp

place it soon bursts the sack. Calcium oxide cannot stand alone under

ordinary atmospheric conditions, but must take up water to form a more

steady substance which is slaked lime or calcium hydroxide. Water is a

chemical mixture of the two gases hydrogen and oxygen, so the slaking of

quicklime means:—

Even slaked lime is not a fully steady substance; for it

takes up carbon dioxide from the air and comes back again to what we started

with—calcium carbonate:—

Quicklime kills both plant and animal life: the plant can

absorb only calcium carbonate as food. If that is so, you might say, why on

earth do we go to all the trouble of burning lime if it has to come back

again to its original chemical state before it can be used? It may be the

same chemically, but in texture it is quite different ; the limestone was

hard rock and this new substance is a finer powder than flour. Just as moist

sugar dissolves quicker in tea than lump, so does this finely powdered lime

dissolve quicker in the acid water of the soil.

6. Forms of Lime

Lime is the name given to three chemical compounds of the

metal calcium—quicklime, slaked lime and carbonate of lime. The last named

is the form in which lime is assimilated by plants, but it must be in very

small particles to be easily dissolved by the soil water which is more or

less acid, depending on whether the soil is "sour" or "sweet."

If you find that a piece of limestone weighs 10 lb.

before it is put into the kiln, it will weigh less than 6 lb. when it is

thoroughly burnt. This same piece left to slake in the air will soon weigh

over 7 lb., and by the time it has become calcium carbonate again it will be

10 lb. of fine powder. The limestone could also be ground to a fine powder

and the result on the land would be the same, except that if you applied a

ton of quick lime to the acre and allowed it to slake and gather weight

naturally you would be saving yourself labour and transport, for you would

have to apply nearly two tons of ground limestone to get the same result.

It seems to be more economical to get finely powdered

calcium carbonate by crushing and grinding limestone than by burning it and

allowing it to slake down, for the use of ground limestone in farming has

steadily crown commoner. The arable land of our crofts would be put on a new

footing if we could completely neutralize the soil acidity and make it

sweet. But we find that the amounts needed for such neutralization are

usually far beyond practical possibilities. Who could afford, for example,

to apply ten tons of quicklime to the acre?

For all practical purposes we can say that a crop needs

half a ton of finely-powdered lime to the acre in the year. We should be

doing quite well if we put on that amount every year, but we usually lime

land at a heavier rate than that, say two tons to the acre, and let it serve

for several years.

We cannot expect to get sufficient manufactured lime

transported to the crofting areas at the present time, so it is in our own

interests to make what use we can of the natural deposits in the West

Highlands and Islands. Most of the old kilns are disused now, though if they

could be repaired easily, the fuel consumption would not be excessive. I

have been told that when the kilns in Strath Kanaird were in use, it was

reckoned that a family could cut peats enough in one day to burn enough

limestone to dress the croft for the year. Two other natural forms of lime

are shell-sand and coral-sand, which are calcium carbonate. Both are good

sweeteners of the soil, but as a particle of shell or coral is relatively

large compared with ground lime, a much heavier dressing is

necessary—preferably ten tons to the acre on land newly reclaimed. This is

hard work, but there is this consolation—that dressing will last twenty

years or more, until the soil acids have completely dissolved the particles.

A crew of three or four men with a big open boat could

soon gather coral-sand enough to dress the arable land of a township with

lime, and as many beaches can be reached by motor lorries the task is even

easier.

After an initial analysis by Government chemists the

shell or coral would be accepted as eligible for the lime subsidy of 50 per

cent. of the cost, including carriage to the croft. Before the war,

shell-sand from the Outer Isles was being put down on the east side of the

Minch at 11s. a ton. Many of us can do it cheaper than that, so with the

subsidy the cost in money for liming in the West need not be great.

Lime tends to sink in the soil, so there is little point

in ploughing it in. A light working with harrows or cultivator is all that

is necessary.

We cultivate ground in order to get it into such physical

condition that it can become a seed bed for domestic plants. Broadly, this

involves drainage and aeration, and the act of ploughing does both of these

operations in the surface layer each year. The result of disturbance of soil

by cultivation is what the farmer calls "tilth," the friable, crumbly

character of the soil which is highly favourable for the early growth of

plants from seed.

There are still many parts of the world where "ploughing"

means no more than a disturbance of the upper soil, such as we obtain with a

cultivator or scuffler, but for two thousand years in Europe, husbandmen

have turned the soil completely over through the action of that cunning

invention, the mouldboard. English ploughing has always been of high

quality, especially during the last 150 years, and it was in the heavy lands

of England that the long steel mouldboard was developed. The action of this

type of plough is to leave an unbroken furrow slice neatly on edge, and the

appearance of a piece of finished work is most pleasing. It is the normal

thing in autumn ploughing to leave the furrow slices well set up so that

they present a large surface to the weather and have beneath them an air

space triangular in section which acts as a drain. Such land breaks down

very easily in spring so that sowing can proceed quickly.

But we cannot follow English practice in the West

Highlands. Autumn ploughing would be detrimental to the ground, because it

would cause leaching of plant food from the soil by rain. We do far better

to leave the stubbles and leas untouched through autumn and early winter,

but I do think we should get on to them earlier in spring. Our arable land

is not getting enough working to get it in good condition or to keep it

clean.

The English plough with its long mouldboard is not the

best type to use up here, where the land is generally light and often stony.

We do far better with the digger plough which has a very short mouldboard of

chilled steel. It was originally developed in America in the nineteenth

century but is commonly used in Britain now for spring cultivation. This

mouldboard lifts the soil high and allows it to fall flat and broken. It is

possible to bury all the winter-growing weeds and so manage the job that the

newly ploughed land is well enough broken up to take the seed immediately.

Nevertheless, we should not be persuaded too easily that such ground is

really ready. It would be better to cultivate it several times and bring up

the weeds to the surface with their roots free of soil so that they are

killed. One ploughing and harrowing a year is not complete cultivation, even

on our light soils. The arrival of the travelling tractor outfit in the

Western crofting districts has tended to make such short preparation of the

ground into the general rule, especially when the month of May is in before

the tractor comes to break the ground.

Wherever there are horses and men we should get busy in

the dry weather of March and be prepared to plough the ground twice if

necessary, and cultivate oftener still. Lea ploughing, of course, cannot be

deeply worked or the turf is brought up again. Our aim should be to lay that

furrow slice as flat as possible, using a skim coulter to pare off the

grassy edge which might show up and grow.

8. The Sub-Soil

When I look at the title of this talk, I can imagine a

good many readers exclaiming, "Sub-soil, indeed, it's little enough top soil

we have here, and then we're on bed rock." Such conditions are not uncommon,

and the best thing we can do then is to build up the depth of what soil

there is with organic matter such as seaweed and dung, in order to increase

the water-holding capacity of the soil. But the greater part of the arable

land in the West has a bottom of peat, glacial silt or shell-sand. A

sub-soil of clay is uncommon here.

Many would-be improvers of our land who have been

accustomed to southern conditions have had a rude shock when they have

delved below the top few inches of West Highland soils. I have heard of

several gardens and some enclosures of arable land being ruined by bringing

an infertile sub-soil to the surface. The best advice is—don't do it. Our

ground is naturally poor and it has taken a long time to get the upper few

inches into workable state. What lies below may contain plant foods, but the

physical and bacterially dead state of the sub-soil renders it utterly

barren.

Why, then, am I wasting time talking about it? The point

is that it is well worth while trying to increase the workable depth of the

soil and gradually tapping

SPRING WORK AT UIG, LEWIS

The peat and the shell sand meet at Uig, one of the

beauty spots of the Hebrides. The effect of shell sand being blown on to

the land in constant small quantities is obvious in the greenness of the

ground at such places as Ardroil on the shores of Uig Bay. This crofter

has an outfit right for the job and the raw materials of fertility are

there behind him—shell sand and seaweed. I believe this bit of country

could produce as early a crop of potatoes as any place in Scotland. The

trouble just now would be freights, which would eat up all the profits.

But it should be remembered that reduction in freight charges needs

organization in the townships as well as action elsewhere.

the mineral plant foods which are lying down there

unused, or breaking up a little more of the peat so that it will act like

soil. Unless the sub-soil is shell-sand, we can take it for granted that it

is very sour, and we must apply lime if we are going to disturb that

sub-soil so that the soil acids may be neutralized and some of the mineral

salts liberated.

A sub-soiling plough has a frame much like an ordinary

plough, but instead of there being a coulter, share and mouldboard, there is

a big tine or prong which goes down the horse-walk after the normal furrow

has been turned and breaks up what lies below to a depth varying from 4 to 9

inches. The ordinary plough then follows and the sub-soil is not brought to

the top to bury the working soil. This breaking up of the sub-soil —assuming

the drainage to have been made good—will allow air to get down into it,

which in its turn will allow seepage of lime from above and the percolation

of organic matter and soil bacteria which are a necessity for the proper

making of soil. Thereafter, plant roots will make their way down and will

help both to drain and aerate the sub-soil as well as add to its nutritive

store.

I should not have bothered to say much about sub-soiling

in the West Highlands were it not that plough pans are very common. A "pan"

is a hard stratum in the soil just below the normal ploughing depth, and in

itself possibly not more than an inch deep. A plough pan results from

constantly ploughing at one depth and is caused by the laying down of iron

salts drained from the upper soil. The pan is usually impervious and does

much to lessen the efficiency of drainage, as well as preventing plant roots

getting down to what they might gather from the sub-soil. If you are working

on a garden scale, you can tackle the pan by trenching as deep as you can

and then going along the bottom of the trench with a pick to loosen the pan

and the sub-soil below, but for anything bigger you would be advised to rig

up a plough with a deep tine. Once the pan is broken, an attempt should be

made at deeper cultivation, and after an adequate liming, deep rooting crops

should be sown.

By careful sub-soiling we bring more soil into

cultivation and achieve something almost as good as increasing our acreage.