|

The lighthouses on the Firth of Clyde provide a

complete system of distinctive illumination. Thus, going down the

channel from Greenock, we have on the east side the Cloch,

white fixed light; on the opposite side the Gantocks, 2

fixed red lights; and Toward, whit a flashing light; on the island

of Gumbrae, the Cumbrae light, white, fixed; on Holy Island,

2 fixed lights, green above and red below; on Pladda, 2 fixed white

lights; on Turn-berry Point on the Ayrshire coast, one

white flashing light; and on Corsewall, near Loch Ryan, a white and

red revolving light; on Ailsa Craig, one white flashing light; and

on Davaar Island (Campbeltown), a white revolving light; whilst on

Sanda there is a white intermittent light; on the Mull of Cantyre, a

white fixed light; and on Rathlin Island, to the west of the Mull,

there are two white lights—the upper intermittent, and the

lower fixed. Besides this there are fog-signalling arrangements at

the Cloch, Toward, Cumbrae, Pladda, Sanda, Bull, Ailsa, and Rathlin

lighthouses.

Since 1829 a beacon, consisting of a stone tower, has

stood on the Gantocks reef. The light, as already noted, is two red

lights placed vertically, and is obtained from a gas supply kept in

a tank, arranged as in the case of the lighted buoys on Skelmorlie

bank and in the river channel above Greenock. The lighting of the

river above Greenock consists of Beacons, Ships and Buoys, the

lights displayed by these being obtained from gas contained in iron

tanks in the two first mentioned; in the latter, the buoy itself

forms the tank. These buoys are from 7 to 9 feet in diameter, and

contain sufficient gas to provide for burning throughout the whole

24 hours, during periods varying from 7 weeks to 14 weeks. The gas

is forced in under pressure until it attains to a pressure of about

100 lbs. to the square inch, the variation of pressure due to

reduction in quantity being regulated at the light by controlling

apparatus.

The difficulty of giving a distinctive character to

the constantly increasing number of lights around our coasts has

brought out various suggestions, one of which by Sir Wm. Thomson

consists in giving the distinctive character, by causing the light

to blink rapidly or slowly in certain arranged periods. The

light 011 Craigmore pier at Rothesay is of this character. Speaking

on this subject, Sir Wm. Thomson, who has devoted much attention to

lighthouse characteristics, groups these under three heads, viz.:

“I. Flashing lights; II. Fixed lights; and III. Occulting or

eclipsing lights.” “In the flashing light, the light is only visible

fora short time—a fraction of a second, or from that to five or six

seconds—and then disappears; and for a much longer time than the

duration of the flash it remains invisible, until it again flashes

out as before. In the fixed light there is no distinguishing

characteristic whatever, but merely a light seen shining

continuously and uniformly. Characteristic distinction is given by a

short eclipse or by a very rapid group of two or three short

eclipses, or of short and longer eclipses recurring at regular

periods— ‘flashes of darkness,’ as they have been called—cutting

out, as it were, from the light its mark, by which it may be

distinguished and recognized to be itself and nothing else, in the

very short time (from half-second at the least, to seven seconds at

the most) occupied by the group of eclipses.” The attempt to

distinguish flashing lights simply by their respective length of

period was found to require some improvement, and colour in some

cases was introduced, and afterwards a system of triple flashes; the

latter was found to be the most successful, although in some cases

the movement is rather slow to the sailor who is anxiously

endeavouring to read his position from the character of the light.

In speaking of the occulting or eclipsing lights, Sir Wm. Thomson

says, “ the only systematic means of giving characteristic quality

to a fixed light is by means of occultations or eclipses; and hence

the origin of the ‘ Occulting ’ or ‘ Eclipsing light.’ We may,

accordingly, look forward to all, or nearly all, the important fixed

lights of our coast being, without any very long delay, converted

into lights of this class.” Several of these occulting lights are

now exhibited on the English, Irish, and Scotch coasts.

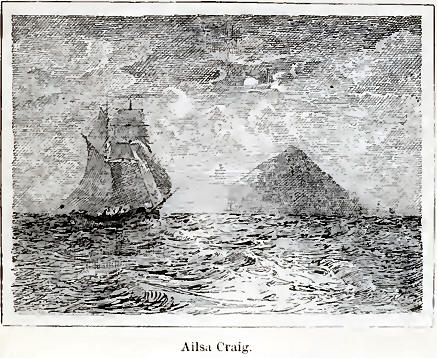

Ailsa Craig, although lying very much in the fair-way

of the channel—it is situated about 10 miles west from Girvan and 12

south from Pladda—does not seem to have called for special attention

in the way of lighthouse requirements; its great bulk, unless in

very dark nights or foggy days, indicating its whereabouts. There

were, however, difficulties in dealing with it as a lighthouse

station, as from the steep, and in some places precipitous nature of

its sides, no point offered itself readily for erecting such a

structure. Again, from its great height, the summit was unsuitable,

being frequently hid in clouds. Several accidents to vessels having

occurred, however, it was determined to erect not only a lighthouse

but foghorns as well, and in 1SS3 works of this character were

commenced and finished in 1886. The ligbt-tower, 25 feet high, is

placed on the eastern side, where the only fiattish bit of shore

exists. It is stated in technical language as “a dioptric

third-order flashing white light,” which, being placed about 60 feet

above the water, has a range of visibility from the deck of a vessel

of 13 nautical miles, through an are of 252°. The light is obtained

from the combustion of gas made from mineral oil, this gas is also

used to drive the engine for condensing the air required by the

fog-horns. Ailsa Craig, therefore, has now become a centre of

applied science, the latest improvements in the machinery required

being here developed.

A small ruined square tower, about 10 or 50 feet in

height, stands at an elevation of about 100 feet on the east side,

and on the opposite side the ruins of what appears to have been a

church may be seen. Recently during the excavations required to be

made in connection with the new lighthouse and fog-signalling

machinery which have been erected on the rock, two ancient graves,

containing human bones, were discovered. According to some, the

tower referred to was one of the line of watch-towers erected many

centuries ago to guard our coasts. Others again regard it as having

been a monkish establishment.

In an article which appeared recently in the Glasgow

Herald, entitled, “A Forgotten Chapter in Scottish History,” it

appears that Ailsa Craig was the scene of a warlike episode in the

year 1597, when Andrew Knox, minister at Paisley, determined to

frustrate an attempt by Hew Barclay, Laird of Ladylands, to assist

the designs of the King of Spain on this country. The object of the

conspirators being “ to take and surprise the island and house of

Aylsaie in the mouth of the Clyde, a place of great strength.” The

government of the day remaining inactive Andrew Knox took the matter

in hand, and “ solved the difficulty by taking possession of Ailsa

Craig, at the head of a small body of nineteen men, with whom he

stationed himself on the solitary rock to await the course of

events. Before long Ladylands, ignorant of Knox’s movements, and

wholly unconscious of the ambush laid for him, sailed to Ailsa with

thirteen of his fellow-conspirators, intending ‘ to have fortefeit

and victuallit the same for the ressett and comforte of the Spanishe

armey, luiked for be him to have cum and arryvit.’ On reaching the

spit of shingle on the east side, which affords the only

landing-place, he found himself suddenly opposed by a band of

determined men, who at once ‘forgadderit with him and his compliceis,

tuke sum of his assockitis and desirit himself e to rander and be

takin with thame, qulia wer his awne freindis, meaning nawayes his

hurte nor drawinge of his blude.’ Though taken at a disadvantage the

laird was not of a temper to yield without a struggle; ‘withdrawing

himself within the sey cant,’ he resolutely defended himself against

his opponents till, having been forced to retreat step by step to

the very edge of the cliff, he was thrust ‘ backwart in the deip,

drownit and per-islieit in his awne wilfull and disperat resolutioun.’

In the heat of the struggle no attention had been given to the

mooring of the boat in which Ladylands and his accomplices had come

across. Not till the skirmish had ceased was it discovered that it

had drifted out to sea, bearing with it the laird’s ‘coders’ and the

important documents which these were believed to contain. This

untoward accident, however, delayed the clearing up of the plot but

for a short time. A few days later the masterless craft was picked

up off South Annan. In Ladylands’ coffers were found, as had been

expected, letters which revealed the whole extent and importance of

the treasonable scheme in which he had been en«a#ed.

It appeared ‘ that the conspiracyc to have been

accomplished by the takinge and forcinge of Ailsa was devysed by the

larde of Ladylands, Corronall (Colonel) Hakerson, and the Spanish

Ambassador.’ ”

The stone of Ailsa Craig has long been celebrated for

the making of curling-stones for the lovers of the “roaring game,”

which was graphically described some years ago in Blackwood:

“It’s an uncolike story that baith Whig and Tory

Maun aye colly-shangy like clogs ower a bane;

And a’ denominations are wantin’ in patience,

For nae Kirk will thole to let ithers alane;

But in fine frosty weather let a’ meet thegither,

Wl a broom in their haun’ and a stane by the tee,

And then, by my certes, ye’ll see boo a’ parties

Like brithers will love, and like brithers agree!”

The curling-stones are quarried out of various parts

of the rock, and are afterwards cut and polished principally at

Mauchline, Ayrshire. They weigh, when finished, from 35 to 40 lbs.,

and are generally of a grayish colour shaded Avith a reddish or

greenish hue. As the stone is of a very compact, fine-grained

character, they take a fine polish, some of them being highly

ornamental in the smoothness of surface and fine tone of colour. The

bright polish is reserved for one of the surfaces, say the top of

the stone; but as the handle can be shifted from one surface to the

other the player can use top or bottom according as the ice is dull

or keen.

The rock has a somewhat elliptical base, measuring

about 1200 yards long by 750 yards broad; the form is roughly

conical, rising to a height of 1114 feet. Geologically it is

composed of syenitic trap of a gray colour with reddish patches. On

the west and south-west there are precipices, where the rock takes a

columnar form.

Ailsa Craig is the home of the solan goose and his

feathered relatives, puffins, kittiwakes (white gulls), and

guillemots, the familiar “dooker” of the Clyde. The blind -worm,

measuring several inches in length, is also common.

Most of the Clyde lighthouses were established many

years ago, the present lighthouse on the Lesser Cumbrae being

erected in 1757. The old beacon tower on the top of the island was

built in 1750.

The Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce were also early

alive to the necessity of lighting the coast, for it appears that in

1774 they made a visit to the Isle of May to see what improvement

could be made on the uncertain light, due to the burning of coals,

already existing on that island.

A brilliant electric light is now shown from the

lighthouse on the May. It appears that at one time lighthouses were

in some cases family property, with a right of toll, from which a

rising revenue was obtained. Outlying lighthouses and their keepers

are much more exposed to vicissitudes than those on shore. The

famous Eddystone has now its fourth tower erected upon it.

Winstanley, the builder of the first tower on that rock, perished

with his structure in the furious storm of 1703.

Ailsa Craig, like the Bass Rock in the Firth of

Forth, stands out prominently to the ej^e from the wide stretch of

water around. The Craig, unlike its eastern counterpart, is not

noticeable in the political history of Scotland as a prison-house.

In viewing it, therefore, from the swiftly passing deep-sea steamer,

or in visiting it with a party of pleasure, there is nothing in the

Craig to recall any special events connected with Scottish history

or to depress the spirits by the surroundings calling up

associations of a grim and hard-hearted past. And so as we see the

old Craig looming grandly in the horizon, and watch it as we

approach rising higher and higher above the swelling waves of the

North Channel, we can look upon it as a magnificent rock standing

sentinel-like, always at its post, welcoming the homeward-bound and

speeding the departing ship—its great mass, like all simple masses

whether of nature or art, satisfying the eye with its large outline,

and creating a feeling of restfulness in the beholder. |