|

The defensive condition of the Firth of Cl}’de has

occupied some attention recently, and measures have been taken,

based upon a government survey and report, to protect the entrance

of the river at the Tail of the Bank at Fort Matilda by arranging

for the placing of mines. The following extract, from a scheme

proposed by Major-general Sir Andrew Clark, Inspector-general of

Fortifications, published in the daily papers July, 1885, is of much

interest:—

“The vast national importance of the shipbuilding

industries of the Clyde, however, and its position as one of the two

great western commercial ports of the country, render defence

absolutely necessary. During war with a European power the security

of the Clyde and Mersey would be vital to the food supply of the

people; while the whole of the shipbuilding energies there

concentrated would be required to create and maintain the great

supplementary force which the peace navy of the country would need.

Such a port as the Clyde has, therefore, a military as well as a

commercial importance, and its adequate defence becomes a national

necessity. Glasgow, approached by a long, narrow channel, is

eminently defensible against a naval attack. There is not sufficient

water to allow the larger ironclads to move up the river; the

sinking of a single ship would effectually bar the approach; hut the

maintenance of the free navigation of the Clyde during war is a

matter of necessity, and such an expedient is inadmissible, except

as a last resort. It becomes necessary, therefore, to create a main

line of defence at some point which shall serve as an absolute bar

to the progress of a squadron. Such a bar can be created only by

heavy guns, in combination with submarine mines. Thus the position

selected must lend itself to both these methods of defence.” In

connection with this it may be stated that there is now a Mining

Volunteer Corps, who practise the laying and placing in position of

both ground and mechanical mines. These are iron cases filled with

guncotton, and can be fired by electricity from the shore.

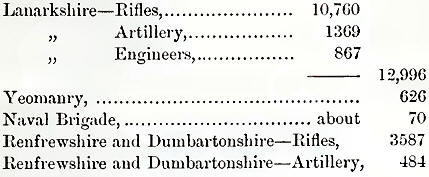

The strength of the volunteer forces in the Clyde

district is as follows:—

The total strength of the volunteers in Great Britain

appears to he about 228,000. The Tactical Society have mapped out

the country to facilitate military defensive operations. The Boys’

Brigade movement, started in Glasgow some years ago, now numbers

about 6000. The primary object of this movement is to improve the

boys morally and physically, but from their great aptness in

learning the elements of drill it is likely that the volunteer ranks

will be afterwards increased from this body.

The present Fort Matilda is the successor of an

earlier battery, erected further up the river in 1703; it was

afterwards strengthened during; the American war, and replaced in

1812. About the close of the last century, when the stirring events

in France led us to fear invasion, a battery of several 18-pounders

was placed on the east side of the Bay of Rothesay, some of the guns

being still there beside the present aquarium.

We have perhaps the most powerful ship in our navy,

the Ajax, guarding the river.

“Lives there a chief whom Ajax ought to dread—

Ajax, ill all the toils of battle bred I”

So spoke Homer of one of his Grecian heroes.

The Ajax fortunately has not yet been inured to battle; but if ever

that time should come when our fleets have to defend their country,

we may be sure our Ajax will equal the Homeric hero in valour.

We have also an occasional visit of the Channel

Fleet, consisting of half a dozen of our powerful ironclads,

broadside or turret ships a great deal more destructive but far less

picturesque than the old wooden-walls which came sailing up the

river under a cloud of canvas. The great speed of some

recently-built war-ships is specially noticeable—thus the fast

cruiser Australia, built by Messrs. Napier & Sons for Her Majesty’s

government, has attained a speed of about 19 knots on a lengthened

trial. The new Spanish war-ship Reina Recjente, built by Messrs.

James & George Thomson, Clydebank Works, attained on a four-hour

trial an average speed of 2073 knots, with a maximum of fully 21

knots. As this represents about 24 miles per hour, we have a large

and completely equipped war-ship, having a displacement of 5000

tons, with a draught of water of 20 feet, driven at railway speed,

with a power exerted by her triple-expansion engines equal to 11,000

horses. Those who have seen this vessel sailing along through the

narrow waters of the firth, throwing up a high and crested wave from

her bows, which made vessels plunge and roll, and finally broke

along the shore like the surf in a gale of wind, will not readily

forget the sight. Torpedo boats show also railway speeds of 25 and

30 miles an hour. Great speed, however, cannot be obtained with

heavy armour, and as the guns are likely to gain in power in a

faster ratio than the defensive character of the armour, we may yet

see history repeating itself; and as the coats of mail of the old

knight proved useless against the musket ball, and were in

consequence doffed as an encumbrance, so in time the armour plating

of our modern war-ships may disappear, and the smart swift cruiser

with heavy guns of long range take her place.

All these defences are still thought to be necessary

even amid the enlightenment of the present day when the peaceful

arts are so largely cultivated. Coleridge appears to believe in the

efficiency of the “silver streak” for defence when he says:

And Ocean mid his uproar wild

Speaks safety to his island-child;

Hence for many a fearless age

Has social quiet loved thy shore,

Nor ever proud invaders’ rage

Or sacked thy towers, or stained thy fields with gore.”

The sister ship to the Australia, the Galatea, has

attained on trial a mean speed of fully 19 knots. Like

the Australia, this vessel is fitted with triple-expansion engines

at the suggestion of Dr. Kirk. So that these two ships are specially

interesting as the first vessels of her majesty’s navy to be so

fitted. It further appears from the results of these trial trips

that the weight of the engines and boilers was comparatively light

for the power developed. The Clyde has also the honour of having

first applied the compound engine to her majesty’s

war-ship Constance, which was fitted with these engines by Messrs.

Randolph, Elder, & Co. in 1863.

Forced draught is now being used at sea, a comparison

of the results obtained by this and ordinary draught in the same

vessel being shown in the trials of her majesty’s Galatea, when,

without special air-pressure, the steam-pressure was 130 lbs.;

vacuum, 27'825 inches; the revolutions, 101; the horse-power being

5871; the corresponding speed was about 17.4 knots. With forced

draught the following results were got: steam-pressure, 138 lbs.;

vacuum, 27195 inches; revolutions, 113½; indicated horse-power,

9219; speed, 19‘021 knots; the forced draught equal to 1.15 inch on

the water-gauge. |